Business Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quincy College Catalog 2018-2019

Quincy College Catalog 2018-2019 The College of the South ShoreTM | www.quincycollege.edu | 800.698.1700 The information in this publication is provided solely for the convenience of the reader, and Quincy College expressly disclaims any liability which may otherwise be incurred. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this publication, the College reserves the right to make changes at any time with respect to course offerings, degree requirements, services provided, or any other subject addressed in this publication. School Profile Quincy College Quincy College is a fully-accredited two-year college offering approximately 475 courses and over a thousand sections each semester, and awarding Associate Degrees and Certificates of completion in a wide variety of studies. 1958 Presidents Place Saville Hall 1250 Hancock Street 24 Saville Avenue Quincy, MA 02169 Quincy, MA 02169 Plymouth Campus 36 Cordage Park Circle Plymouth, MA 02360 617-984-1700 (Quincy Campus) 508-747-0400 (Plymouth Campus) www.quincycollege.edu Students Enrolled 5,343 (Headcount) (Based on end of semester 3,159 FTE (Fall) Fall 2017 data) Gender Ratio 68% Female 32% Male Ethnicity 42% White, Non-Hispanic 27% Black, Non-Hispanic 5% International Students 8% Hispanic 6% Asian or Pacific Islander 2% Two or more races 10% Race/Ethnicity Unknown Age Range 14-92 Average Age 28 Average Class Size 20 Retention Rate (Fall to Fall) 2007-2008 42% 2008-2009 56% 2009-2010 56% 2010-2011 57% 2011-2012 49% 2012-2013 58% 2013-2014 52% 2014-2015 -

Bridgewater State University Salem State University

January 23rd, 2021 Master’s in English Regional Conference Hosted by Bridgewater State University and Salem State University Schedule Conference Organizers 8:30 AM - 9:35 AM From First Wave to Third Wave Feminism: Dr. Halina Adams Literature and Creative Writing Assistant Professor of English 9:35 AM - 10:40 AM Bridgewater State University Pedagogy, Empowerment, and Disempowerment Elizabeth Brady 10:45 AM - 11:50 AM Graduate Assistant Institutional Power of Race and Religion Bridgewater State University 11:50 AM - 12:55 PM Dr. Kimberly Chabot Davis Equity, Disability Studies, and Critical Race Pedagogy Professor of English; Graduate Coordinator 1:00 PM - 2:05 PM Bridgewater State University Metatextuality in Modern and Postmodern Culture Dr. Theresa DeFrancis 2:05 PM - 3:10 PM Associate Professor of English; Graduate Coordinator Salem State University Healing, Nature, and Community in Ecocriticism and Native American Literature Hannah Drew 3:15 PM - 4:05 PM Graduate Assistant Popular Culture and Group Identity Salem State University 4:05 PM - 5:10 PM Dr. Roopika Risam Writing, Rhetoric, and Visual Literacy Assistant Professor of English; Program Coordinator Salem State University Conference Zoom Link Dr. Keja Valens Professor of English; Graduate Coordinator Salem State University MERC Website 2 3 From First Wave to Third Wave Pedagogy, Empowerment, and Feminism: Literature and Disempowerment Creative Writing 9:35 AM - 10:40 AM 8:30 AM - 9:35 AM Moderated by Dr. Theresa DeFrancis, Salem State University Moderated by Dr. Maria Hegbloom, -

LINGUA FRANCA a BI-ANNUAL NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED by FOREIGN LANGUAGES at SALEM STATE UNIVERSITY Salemstate.Edu/Languages Volume 9 • Issue 1 • Fall 2011

LINGUA FRANCA A BI-ANNUAL NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED BY FOREIGN LANGUAGES AT SALEM STATE UNIVERSITY salemstate.edu/languages Volume 9 • Issue 1 • Fall 2011 “EVERYONE SHOULD LEARN A SECOND LANGUAGE” A CONVERSATION WITH K. BREWER DORAN, DEAN OF THE BERTOLON SCHOOL OF BUSINESS INSIDE THIS ISSUE By Elizabeth Blood, foreign languages Business and Language page 1 K. Brewer Doran, Dean of the Bertolon School of Business Hispanophile in Paris page 1 and well-known specialist in global and cross-cultural marketing and decision-making, knows first-hand the importance of Department News page 2 understanding different cultures and learning languages. Fluent MaFLA Conference page 3 in English and French, Dean Doran is also conversant in German and Swahili, and knows some Spanish and Chinese. During HOPE Award page 4 her undergraduate and graduate studies, Dean Doran studied Photo Contest page 4 and lived in Kenya, Germany, Canada, and China. She was also awarded a Fulbright Fellowship to live in Uganda. During Il Mio Destino page 5 her career in the private sector and her many business-related Salem’s Hispanics page 5 academic research projects, she has traveled to over 80 countries on all seven continents and to all 50 U.S. states. Dean Doran has, Teaching in Italy page 6 quite literally, been around the world. When asked whether today’s students should be encouraged to Arabic and Language page 7 study different languages and cultures, Dean Doran emphatically Teaching in Lugo, Spain page 8 responded “I think everyone should learn a second language. While it’s not necessary in today’s business world, not being able to speak another language puts us, as Americans, at a disadvantage. -

Business Law Review

Published by Husson University Bangor, Maine For the NORTH ATLANTIC REGIONAL BUSINESS LAW ASSOCIATION EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Marie E. Hansen Husson University William B. Read Husson University BOARD OF EDITORS Michelle D. Bazin Anne-Marie G. Hakstian University of Massachusetts-Lowell Salem State University Robert C. Bird Carter H. Manny University of Connecticut University of Southern Maine Elizabeth A. Brown Christine N. O’Brien Bentley University Boston College Margaret T. Campbell Lucille M. Ponte Husson University Florida Coastal School of Law Gerald R. Ferrera Patricia Q. Robertson Bentley University Arkansas State University Stephanie M. Greene Brien C. Walton Boston College Husson University William E. Greenspan Thomas L. Wesner University of Bridgeport Boston College i GUIDELINES FOR 2019 Papers presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting and Conference will be considered for publication in the Business Law Review. In order to permit blind peer refereeing of manuscripts for the 2019 Business Law Review, papers must not identify the author or the author’s institutional affiliation. A separate cover page should contain the title, the author's name, affiliation, and address. If you are presenting a paper and would like to have it considered for publication, you must submit one clean copy by email no later than March 29, 2019 to: William B. Read Husson University 1 College Circle Bangor, Maine 04401 [email protected] The Board of Editors of the Business Law Review will judge each paper on its scholarly contribution, research quality, topic interest (related to business law or the legal environment), writing quality, and readiness for publication. Please note that, although you are welcome to present papers relating to teaching business law, those papers will not be eligible for publication in the Business Law Review. -

BSU Annual Security & Fire Safety Report for 2020

Safety on Campus Annual Security & Fire Safety Report for 2020 2017, 2018, 2019 Statistics | Published 2020 Table of Contents From the Chief of Police…………………………………………………………… 3 1 2020 ANNUAL SECURITY REPORT PREPARATION OF THE ANNUAL SECURITY 4 REPORT AND DISCLOSURE OF CRIME STATISTICS…………….............................. About the Bridgewater State University Police Department…………………….. 4 Safety, Our Number One Priority……………………………………………................... 4 University Law Enforcement Authority & Jurisdiction……………………............ 5 Memorandum of Understanding with Local, State, and Regional Agencies. 6 REPORTING CRIMES AND OTHER EMEGENCIES Statement for Reporting a Crime or Emergency on Campus………………......... 6 Mandatory Crime Reporting Policy…………………………………………..................... 6 Campus Security Authorities…………………………………………………….................... 6 Voluntary, Confidential Reporting…………………………………………….................... 7 STATEMENTS CONCERNING TIMLEY WARNINGS & EMERGENCIES Statement of Policy Addressing Timely Warnings……………………………............ 8 Policy Regarding Immediate Response & Evacuation Procedures………......... 10 Policy Regarding Emergency Notifications – Immediate Threat……………....... 11 STATEMENTS CONCERNING SECURITY POLICIES Safety & Security Awareness and Crime Prevention Programs…………………… 13 Emergency Preparedness…………………………………………………………………………… 14 Statement of Policy Concerning Facility Security & Access…………………………. 16 Statement of Policy for Addressing Criminal Activity Off Campus……….......... 17 Statement of Policy Addressing Alcohol, -

Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 Department Of

Updated December 2020 CURRICULUM VITAE MATTHEW K. NOCK, PH.D. Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 Department of Psychology Telephone: (617) 496-4484 William James Hall, 1220 E-mail: [email protected] 33 Kirkland Street http://nocklab.fas.harvard.edu/ EDUCATION 1995 Boston University, B.A. (Psychology) 2000 Yale University, M.S. (Psychology) 2001 Yale University, M.Phil. (Psychology) 2003 Yale University, Ph.D. (Psychology) PRIMARY ACADEMIC APPOINTMENT 2003-2007 Harvard University, Assistant Professor of Psychology 2007-2010 Harvard University, John L. Loeb Associate Professor of the Social Sciences 2010-2017 Harvard University, Professor of Psychology 2017 – Harvard University, Edgar Pierce Professor of Psychology 2019-2024 Harvard University, Harvard College Professor 2019 – Harvard University, Chair, Department of Psychology ADDITIONAL ACADEMIC/SCIENTIFIC APPOINTMENTS 2009 – Harvard University, Center on the Developing Child, Affiliated Faculty/Steering Committee 2013 – Boston Children’s Hospital, Associate Scientific Research Staff 2015 – Massachusetts General Hospital, Research Scientist 2017 – Franciscan Children’s Hospital, Research Scientist 2019 – American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Scientific Council HONORS AND AWARDS 1995 Teaching Assistant of the Year Award (Psychology), Boston University 1998-2002 University Fellowship, Yale University 2001 Graduate Student Research Award, American Psychological Association, Division 12, Section VII 2003 James B. Grossman Dissertation Prize, Yale Graduate School of Arts & Sciences -

MA State Universities Title IX Sexual Harassment Policy

MA State Universities Title IX Sexual Harassment Policy BRIDGEWATER STATE UNIVERSITY FITCHBURG STATE UNIVERSITY FRAMINGHAM STATE UNIVERSITY MASSACHUSETTS COLLEGE OF ART AND DESIGN MASSACHUSETTS COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS MASSACHUSETTS MARITIME ACADEMY SALEM STATE UNIVERSITY WESTFIELD STATE UNIVERSITY WORCESTER STATE UNIVERSITY Effective Date: August 14, 2020 2431763_1 Contents Article I. Policy Introduction ................................................................................................... 3 Article II. Policy Definitions ...................................................................................................... 4 Article III. Policy Application ..................................................................................................... 8 Article IV. Policy Dissemination ................................................................................................ 8 Article V. Policy Offenses ......................................................................................................... 9 Section V.1 Title IX Prohibited Sexual Harassment .................................................................. 9 Section V.2 Retaliation ........................................................................................................... 10 Section V.3 Conduct That Is Not Prohibited ........................................................................... 11 Article VI. Consensual Relationships ....................................................................................... 11 Section -

Unrequited Love in Fall 2017, Or Where Did Umaine's Admitted-But-Nonmatriculating Students

Unrequited love in fall 2017, or Where did UMaine’s admitted-but-nonmatriculating students go? Data from the National Student Clearinghouse UMaine Office of Institutional Research 30 November 2017 ________________________________________ The National Student Clearinghouse is a non-federal, independent, nonprofit organization that serves as a repository for student data on enrollment and degree attainment. More than 3,600 institutions of higher education participate in the Clearinghouse enrollment verification service, capturing over 98% of currently enrolled college students in the United States (http://www.studentclearinghouse.org/colleges/studenttracker/).1 The Office of Institutional Research annually uses this service to obtain the names of schools that UMaine’s admitted-but-nonmatriculating undergraduate applicants chose to attend (first- time students only). The present report summarizes our most recent effort in this regard. Specifically, we determined the destination school for the 8,755 undergraduate applicants who: • were admitted at UMaine for fall 2017, • did not matriculate at UMaine, and • enrolled at another school instead.2 Caveat: These 8,755 students account for 89% of the first-time-student applicants who were admitted at UMaine for fall 2017 but did not matriculate here.3 The remaining 11% reflect the fact that some individuals: • did not enroll at any school in fall 2017, • enrolled elsewhere but did not permit the Clearinghouse to release their enrollment information (there were 63 such cases), or • enrolled elsewhere but the destination school is not a Clearinghouse participant. Thus although a marvelous data source, the Clearinghouse is not without imperfections. 1 The 2010 report, College graduation rates: Behind the numbers (American Council of Education) includes an informative overview of the National Student Clearinghouse (see pp. -

Summer 2011 Summer

Inside: Making the Case for Public Higher Education – page 3 Perspective MSCA Newsletter Patricia V. Markunas, editor NEA/MTA/MSCA Summer 2011 DGCE Bargaining Team Reviews Survey Results, Preps Proposal Susan Dargan, Chair, DGCE Bargaining Committee The DGCE bargaining team met at Framingham State University on June 7 to review the results of the recent member survey, discuss bargaining strategy, and outline a draft MSCA proposal based on survey findings. Three hundred twenty-six (326) members responded to the survey, which measured perceptions of job-related issues in DGCE through the use of close- and open-ended questionnaire items. The majority of survey respondents reported that they taught full-time in the day division and DGCE (68%), followed by those who reported that they taught part-time in the day division and DGCE (18%), DGCE only (11%), and other (3%). After reviewing the survey findings, the bargaining committee prepared a conceptual MSCA proposal. MTA consultant Robert Whalen is drafting this proposal for the MSCA Board of Directors to review and approve on a date to be determined. The current agreement expires on December 31, 2011. The team consists of: Sue Dargan (Chair, Framingham), Glenn Pavlicek (Bridgewater), Sean Goodlett (Fitchburg), Ben Ryterband (Mass Art), Gerald Concannon (Mass Maritime), David Goodof (Salem), Ken Haar (Westfield), Anne Falke (Worcester) and C.J. O’Donnell (MSCA President). Team alternates include: Jean Stonehouse (Bridgewater), Gary Merlo (Westfield), Robert Donohue (Framingham), Sam Schlosberg (Mass Art), Arthur Aldrich Pat Markunas (Mass Maritime), and Paul McGee (Salem). MTA consultant Robert Whalen MSCA/DGCE Bargaining Committee Chair Sue Dargan (Framingham) attends to will serve as the team’s chief negotiator. -

Equal Opportunity Plan 81320

EQUAL OPPORTUNITY, DIVERSITY AND AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PLAN BRIDGEWATER STATE UNIVERSITY FITCHBURG STATE UNIVERSITY FRAMINGHAM STATE UNIVERSITY MASSACHUSETTS COLLEGE OF ART AND DESIGN MASSACHUSETTS COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS MASSACHUSETTS MARITIME ACADEMY SALEM STATE UNIVERSITY WESTFIELD STATE UNIVERSITY WORCESTER STATE UNIVERSITY APPROVED BY THE BOARD OF HIGHER EDUCATION: SEPTEMBER 28, 2018 Table of Contents I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Policy Statement of Non-Discrimination and Diversity .................................................................... 1 III. Scope and Duration ......................................................................................................................... 2 IV. Plan Definitions and Terms ............................................................................................................. 4 V. Policy Against Discrimination, Discriminatory Harassment and Retaliation ................................... 9 VI. Sexual Violence Policy ................................................................................................................... 13 VII. Policies For Reasonable Accommodations For Persons with Disabilities .................................... 46 VIII. Policy Against Discrimination in Employment Based on Pregnancy and Pregnancy-Related Conditions And Requirement to Provide Reasonable Accommodations .......................................... 47 IX. Mandatory -

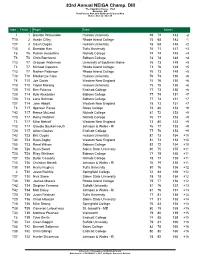

83Rd Annual NEIGA Champ. DIII the Captains Course - Port Brewster, MA Port Course Men and Starboard Course Men Dates: Oct 22 - Oct 23

83rd Annual NEIGA Champ. DIII The Captains Course - Port Brewster, MA Port Course Men and Starboard Course Men Dates: Oct 22 - Oct 23 Start Finish Player Team Scores 1 1 Daulton Wickenden Husson University 69 73 142 -2 T10 2 Austin Cilley Rhode Island College 75 68 143 -1 T27 3 Gavin Dugas Husson University 78 68 146 +2 T13 4 Brandon Karr Tufts University 76 71 147 +3 T6 T5 Patrick Hesseltine Nichols College 74 74 148 +4 T6 T5 Chris Bornhorst Babson College 74 74 148 +4 T13 T7 Grayson Waterman University of Southern Maine 76 73 149 +5 T3 T7 Michael Caparco Rhode Island College 73 76 149 +5 T13 T7 Nathan Patterson Rhode Island College 76 73 149 +5 T13 T10 Mackenzie Clow Husson University 76 74 150 +6 T6 T10 Joe Ciolek Western New England 74 76 150 +6 T10 T10 Taylor Morang Husson University 75 75 150 +6 T20 T10 Ben Palazzo Endicott College 77 73 150 +6 T20 T14 Kyle Alexander Babson College 77 74 151 +7 T20 T14 Lane Bohman Babson College 77 74 151 +7 T27 T14 John Abbott Western New England 78 73 151 +7 T3 T17 Spencer Pierce Bates College 73 80 153 +9 T42 T17 Reece McLeod Nichols College 81 72 153 +9 T13 T17 Remy Fletcher Nichols College 76 77 153 +9 T3 T17 Mike Metcalf Western New England 73 80 153 +9 T13 T17 Claudio Soukamneuth Johnson & Wales - RI 76 77 153 +9 T20 T17 Athan Goulas Endicott College 77 76 153 +9 T42 T23 Eric Dugas Husson University 81 73 154 +10 T42 T23 Ryan Zogby Western New England 81 73 154 +10 T55 T23 Reed Wilson Babson College 82 72 154 +10 T38 T26 Ryan Swart Salem State University 80 75 155 +11 T20 T26 Riley Whitham -

JAMES NOONAN, Ed.D

JAMES NOONAN, Ed.D. CONTACT Salem State University [email protected] School of Education http://scholar.harvard.edu/jmnoonan 352 Lafayette Street Twitter: @_jmnoonan Salem, MA 01970 USA +1 617-953-1697 (cell) +1 978-542-3040 (office) ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS SALEM STATE UNIVERSITY, School of Education, Salem, MA Assistant Professor (September 2019-present) BEYOND TEST SCORES PROJECT, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA Research Partner (September 2020-present) EDUCATION HARVARD GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Ed.D., Culture, Communities, and Education (November 2016) Thesis: Teachers Learning: Engagement, Identity, and Agency in Powerful Professional Development Dr. Meira Levinson (chair), Dr. Howard Gardner, Dr. Jal Mehta HARVARD GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Ed.M. International Education Policy (May 2010) BOSTON UNIVERSITY B.A., English (May 1997) B.S., English Education (May 1997) CURRENT RESEARCH PROJECTS + DATA SOURCES Professional Learning in a Pandemic, supported by a Salem State University Flash Grant With Dr. Megin Charner-Laird and Dr. Jacy Ippolito (Salem State University) national survey of more than 200 K-12 educators with follow-up focus groups Unlearning Leadership: A Pilot Study of the Developmental Capacity of Emerging School Leaders, supported by the DeFelice Fund at Salem State University with Dr. Jacy Ippolito and Dr. Megin-Charner Laird (Salem State University) two interview sequence (semi-structured interview and Subject-Object Interview) Updated: August 2021 J. Noonan Page | 2 Exploring the Dynamics of a District-initiated Anti-Racist Reading Group with Dr. Hilary Lustick (UMass Lowell), Dr. Peter Piazza (Center for Collaborative Education, Ashley Carey (UMass Lowell) ethnographic observations, semi-structured interviews Using Data to Empower Communities, funded by the Massachusetts Teachers Association with Dr.