MYCOTAXON Volume 95, Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universidad De Concepción Facultad De Ciencias Naturales Y

Universidad de Concepción Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas Programa de Magister en Ciencias mención Botánica DIVERSIDAD DE MACROHONGOS EN ÁREAS DESÉRTICAS DEL NORTE GRANDE DE CHILE Tesis presentada a la Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas de la Universidad de Concepción para optar al grado de Magister en Ciencias mención Botánica POR: SANDRA CAROLINA TRONCOSO ALARCÓN Profesor Guía: Dr. Götz Palfner Profesora Co-Guía: Dra. Angélica Casanova Mayo 2020 Concepción, Chile AGRADECIMIENTOS Son muchas las personas que han contribuido durante el proceso y conclusión de este trabajo. En primer lugar quiero agradecer al Dr. Götz Palfner, guía de esta tesis y mi profesor desde el año 2014 y a la Dra. Angélica Casanova, quienes con su experiencia se han esforzado en enseñarme y ayudarme a llegar a esta instancia. A mis compañeros de laboratorio, Josefa Binimelis, Catalina Marín y Cristobal Araneda, por la ayuda mutua y compañía que nos pudimos brindar en el laboratorio o durante los viajes que se realizaron para contribuir a esta tesis. A CONAF Atacama y al Proyecto RT2716 “Ecofisiología de Líquenes Antárticos y del desierto de Atacama”, cuyas gestiones o financiamientos permitieron conocer un poco más de la diversidad de hongos y de los bellos paisajes de nuestro desierto chileno. Agradezco al Dr. Pablo Guerrero y a todas las personas que enviaron muestras fúngicas desertícolas al Laboratorio de Micología para identificarlas y que fueron incluidas en esta investigación. También agradezco a mi familia, mis padres, hermanos, abuelos y tíos, que siempre me han apoyado y animado a llevar a cabo mis metas de manera incondicional. -

A New Section and Two New Species of Podaxis (Gasteromycetes) from South Africa

S.Afr.l. Bot., 1989,55(2): 159-164 159 A new section and two new species of Podaxis (Gasteromycetes) from South Africa J.J.R. de Villiers, A. Eicker* and G.C.A. van der Westhuizen Department of Botany, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, 0001 Republic of South Africa Accepted 7 September /988 Podaxis africana De Villiers, Eicker & van der Westhuizen and P. rugospora De Villiers, Eicker & van der Westhuizen, two new species from Transvaal are described and illustrated. A new section, Umbricorticalis De Villiers, Eicker & van der Westhuizen is proposed in the genus Podaxis to accommodate P. africana. Morphologically P. africana resembles P. microporus McKnight but it is distinguished by its large globose, subglobose to broadly ovoid spores, the absence of a 'pin prick' pore structure, the black gleba, and the deep orange to strong brown inner cortex of the stipe. P. rugospora is allied to P. pistillaris (L. ex Pers.) Fr. emend. Morse from which it differs by reason of the hyaline, narrow, flattened, occasionally septate capillitium threads and the grayish-olive, light olive or light to moderate yellowish-brown gleba. The most remarkable character of these new species is the rugose spores. Podaxis africana De Villiers, Eicker & van der Westhuizen en P. rugospora De Villiers, Eicker & van der Westhuizen, twee nuwe spesies van Transvaal word beskryf en ge·illustreer. 'n Nuwe seksie, Umbricorticalis De Villiers, Eicker & van der Westhuizen in die genus Podaxis word voorgestel om P. africana te akkommodeer. Morfologies toon P. africana 'n ooreenkoms met P. microporus McKnight maar word deur die groot bolvormige, subbolvormige tot bykans eiervormige spore, die afwesigheid van 'n 'naaldprik'-porie struktuur, die swart gleba en die diep oranje tot sterk bruin binneste korteks van die stipe. -

Qrno. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 CP 2903 77 100 0 Cfcl3

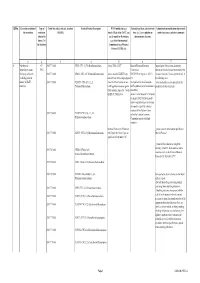

QRNo. General description of Type of Tariff line code(s) affected, based on Detailed Product Description WTO Justification (e.g. National legal basis and entry into Administration, modification of previously the restriction restriction HS(2012) Article XX(g) of the GATT, etc.) force (i.e. Law, regulation or notified measures, and other comments (Symbol in and Grounds for Restriction, administrative decision) Annex 2 of e.g., Other International the Decision) Commitments (e.g. Montreal Protocol, CITES, etc) 12 3 4 5 6 7 1 Prohibition to CP 2903 77 100 0 CFCl3 (CFC-11) Trichlorofluoromethane Article XX(h) GATT Board of Eurasian Economic Import/export of these ozone destroying import/export ozone CP-X Commission substances from/to the customs territory of the destroying substances 2903 77 200 0 CF2Cl2 (CFC-12) Dichlorodifluoromethane Article 46 of the EAEU Treaty DECISION on August 16, 2012 N Eurasian Economic Union is permitted only in (excluding goods in dated 29 may 2014 and paragraphs 134 the following cases: transit) (all EAEU 2903 77 300 0 C2F3Cl3 (CFC-113) 1,1,2- 4 and 37 of the Protocol on non- On legal acts in the field of non- _to be used solely as a raw material for the countries) Trichlorotrifluoroethane tariff regulation measures against tariff regulation (as last amended at 2 production of other chemicals; third countries Annex No. 7 to the June 2016) EAEU of 29 May 2014 Annex 1 to the Decision N 134 dated 16 August 2012 Unit list of goods subject to prohibitions or restrictions on import or export by countries- members of the -

Research Article

Marwa H. E. Elnaiem et al / Int. J. Res. Ayurveda Pharm. 8 (Suppl 3), 2017 Research Article www.ijrap.net MORPHOLOGICAL AND MOLECULAR CHARACTERIZATION OF WILD MUSHROOMS IN KHARTOUM NORTH, SUDAN Marwa H. E. Elnaiem 1, Ahmed A. Mahdi 1,3, Ghazi H. Badawi 2 and Idress H. Attitalla 3* 1Department of Botany & Agric. Biotechnology, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Khartoum, Sudan 2Department of Agronomy, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Khartoum, Sudan 3Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Science, Omar Al-Mukhtar University, Beida, Libya Received on: 26/03/17 Accepted on: 20/05/17 *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] DOI: 10.7897/2277-4343.083197 ABSTRACT In a study of the diversity of wild mushrooms in Sudan, fifty-six samples were collected from various locations in Sharq Elneel and Shambat areas of Khartoum North. Based on ten morphological characteristics, the samples were assigned to fifteen groups, each representing a distinct species. Eleven groups were identified to species level, while the remaining four could not, and it is suggested that they are Agaricales sensu Lato. The most predominant species was Chlorophylum molybdites (15 samples). The identified species belonged to three orders: Agaricales, Phallales and Polyporales. Agaricales was represented by four families (Psathyrellaceae, Lepiotaceae, Podaxaceae and Amanitaceae), but Phallales and Polyporales were represented by only one family each (Phallaceae and Hymenochaetaceae, respectively), each of which included a single species. The genetic diversity of the samples was studied by the RAPD-PCR technique, using six random 10-nucleotide primers. Three of the primers (OPL3, OPL8 and OPQ1) worked on fifty-two of the fifty-six samples and gave a total of 140 bands. -

A Preliminary Checklist of Arizona Macrofungi

A PRELIMINARY CHECKLIST OF ARIZONA MACROFUNGI Scott T. Bates School of Life Sciences Arizona State University PO Box 874601 Tempe, AZ 85287-4601 ABSTRACT A checklist of 1290 species of nonlichenized ascomycetaceous, basidiomycetaceous, and zygomycetaceous macrofungi is presented for the state of Arizona. The checklist was compiled from records of Arizona fungi in scientific publications or herbarium databases. Additional records were obtained from a physical search of herbarium specimens in the University of Arizona’s Robert L. Gilbertson Mycological Herbarium and of the author’s personal herbarium. This publication represents the first comprehensive checklist of macrofungi for Arizona. In all probability, the checklist is far from complete as new species await discovery and some of the species listed are in need of taxonomic revision. The data presented here serve as a baseline for future studies related to fungal biodiversity in Arizona and can contribute to state or national inventories of biota. INTRODUCTION Arizona is a state noted for the diversity of its biotic communities (Brown 1994). Boreal forests found at high altitudes, the ‘Sky Islands’ prevalent in the southern parts of the state, and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa P.& C. Lawson) forests that are widespread in Arizona, all provide rich habitats that sustain numerous species of macrofungi. Even xeric biomes, such as desertscrub and semidesert- grasslands, support a unique mycota, which include rare species such as Itajahya galericulata A. Møller (Long & Stouffer 1943b, Fig. 2c). Although checklists for some groups of fungi present in the state have been published previously (e.g., Gilbertson & Budington 1970, Gilbertson et al. 1974, Gilbertson & Bigelow 1998, Fogel & States 2002), this checklist represents the first comprehensive listing of all macrofungi in the kingdom Eumycota (Fungi) that are known from Arizona. -

Podaxis Pistillaris Reported from Madhya Pradesh, India Patel U

Indian Journal of Fundamental and Applied Life Sciences ISSN: 2231-6345 (Online) An Online International Journal Available at http://www.cibtech.org/jls.htm 2012 Vol. 2 (1) January- March, pp.233 -239 /Patel et al. Research Article PODAXIS PISTILLARIS REPORTED FROM MADHYA PRADESH, INDIA PATEL U. S.1 and *TIWARI A. K.2 Department of Botany, Government Shyam Sunder Agrawal College, Sihora, District Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India *2 Jabalpur Institute of Nursing Science & Research, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India *Author for Correspondence ABSTRACT A basidiomycete collected from Sihora, District Jabalpur is described and illustrated. The fruiting bodies and spores showed variations however, match with the description of Podaxis pistillaris. This is first report of the fungus from Madhya Pradesh, India. Key Words: Comatus, Agaricaceae, Lycoperdaceae, Food, Medicinal INTRODUCTION Sihora road railway station is situated in Jabalpur district of Madhya Pradesh about 17 kilometers south west from Karaundi the center point of India. Its geographical co-ordinates are 230 29’ North and 800 70’ East. Some cylindrical fruiting bodies were incidentally seen on disturbed soil of filling of a pond beside the road going towards Khitola bus stand from railway station. The fungus was initially identified as Coprinus comatus (O. F. Mull.) Pers. Later it was identified as Podaxis pistillaris (L. Pers.) Morse.This fungus is commonly known as False Shaggy Mane due to its resemblance with C. comatus. This species has previously been described and synonymised by few workers (Massee, 1890; Morse, 1933, 1941; Keirle et al., 2004; Drechsler- Santosh , 2008). Podaxis pistillaris earlier has been reported from various parts of India (Bilgrami et al., 1979,81,1991; Jamaluddin et al., 2004). -

2 the Numbers Behind Mushroom Biodiversity

15 2 The Numbers Behind Mushroom Biodiversity Anabela Martins Polytechnic Institute of Bragança, School of Agriculture (IPB-ESA), Portugal 2.1 Origin and Diversity of Fungi Fungi are difficult to preserve and fossilize and due to the poor preservation of most fungal structures, it has been difficult to interpret the fossil record of fungi. Hyphae, the vegetative bodies of fungi, bear few distinctive morphological characteristicss, and organisms as diverse as cyanobacteria, eukaryotic algal groups, and oomycetes can easily be mistaken for them (Taylor & Taylor 1993). Fossils provide minimum ages for divergences and genetic lineages can be much older than even the oldest fossil representative found. According to Berbee and Taylor (2010), molecular clocks (conversion of molecular changes into geological time) calibrated by fossils are the only available tools to estimate timing of evolutionary events in fossil‐poor groups, such as fungi. The arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiotic fungi from the division Glomeromycota, gen- erally accepted as the phylogenetic sister clade to the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, have left the most ancient fossils in the Rhynie Chert of Aberdeenshire in the north of Scotland (400 million years old). The Glomeromycota and several other fungi have been found associated with the preserved tissues of early vascular plants (Taylor et al. 2004a). Fossil spores from these shallow marine sediments from the Ordovician that closely resemble Glomeromycota spores and finely branched hyphae arbuscules within plant cells were clearly preserved in cells of stems of a 400 Ma primitive land plant, Aglaophyton, from Rhynie chert 455–460 Ma in age (Redecker et al. 2000; Remy et al. 1994) and from roots from the Triassic (250–199 Ma) (Berbee & Taylor 2010; Stubblefield et al. -

Characterizing the Assemblage of Wood-Decay Fungi in the Forests of Northwest Arkansas

Journal of Fungi Article Characterizing the Assemblage of Wood-Decay Fungi in the Forests of Northwest Arkansas Nawaf Alshammari 1, Fuad Ameen 2,* , Muneera D. F. AlKahtani 3 and Steven Stephenson 4 1 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Hail, Hail 81451, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 2 Department of Botany & Microbiology, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia 3 Biology Department, College of Science, Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh 11564, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 4 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The study reported herein represents an effort to characterize the wood-decay fungi associated with three study areas representative of the forest ecosystems found in northwest Arkansas. In addition to specimens collected in the field, small pieces of coarse woody debris (usually dead branches) were collected from the three study areas, returned to the laboratory, and placed in plastic incubation chambers to which water was added. Fruiting bodies of fungi appearing in these chambers over a period of several months were collected and processed in the same manner as specimens associated with decaying wood in the field. The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) ribosomal DNA region was sequenced, and these sequences were blasted against the NCBI database. A total of 320 different fungal taxa were recorded, the majority of which could be identified to species. Two hundred thirteen taxa were recorded as field collections, and 68 taxa were recorded from the incubation chambers. Thirty-nine sequences could be recorded only as unidentified taxa. -

New Record of Woldmaria Filicina (Cyphellaceae, Basidiomycota) in Russia

Mycosphere 4 (4): 848–854 (2013) ISSN 2077 7019 www.mycosphere.org Article Mycosphere Copyright © 2013 Online Edition Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/4/4/18 New Record of Woldmaria filicina (Cyphellaceae, Basidiomycota) in Russia Vlasenko VA and Vlasenko AV Central Siberian Botanical Garden, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Zolotodolinskaya, 101, Novosibirsk 630090, Russia Email: [email protected], [email protected] Vlasenko VA, Vlasenko AV 2013 – New Record of Woldmaria filicina (Cyphellaceae, Basidiomycota) in Russia. Mycosphere 4(4), 848–854, Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/4/4/18 Abstract This paper provides information on the new record of Woldmaria filicina in Russia. This rare and interesting member of the cyphellaceous fungi was found in the Novosibirsk Region of Western Siberia in the forest-steppe zone, on dead stems of the previous year of the fern Matteuccia struthiopteris. A description of the species is given along with images of fruiting bodies of the fungus and its microstructures, information on the ecology and general distribution and data on the literature and internet sources. Key words – cyphellaceous fungi – forest-steppe – new data – microhabitats – Woldmaria filicina Introduction This paper is devoted to the description of an interesting member of the cyphellaceous fungi – Woldmaria filicina—found for the first time in the vast area of Siberia. This species was previously known from Europe, including the European part of Russia and the Urals but was found the first time in the forest-steppe zone of Western Siberia. Despite the large scale of the territory and well-studied biodiversity of aphyllophoroid fungi (808 species are known from Western Siberia) this species has not previously been recorded here, and information is provided on the specific substrate and the habitat of the fungus at this new locality. -

Fungi from the Owyhee Region

FUNGI FROM THE OWYHEE REGION OF SOUTHERN IDAHO AND EASTERN OREGON bY Marcia C. Wicklow-Howard and Julie Kaltenecker Boise State University Boise, Idaho Prepared for: Eastside Ecosystem Management Project October 1994 THE OWYHEE REGION The Owyhee Region is south of the Snake River and covers Owyhee County, Idaho, Malheur County, Oregon, and a part of northern Nevada. It extends approximately from 115” to 118” West longitude and is bounded by parallels 41” to 44”. Owyhee County includes 7,662 square miles, Malheur County has 9,861 square miles, and the part of northern Nevada which is in the Owyhee River watershed is about 2,900 square miles. The elevations in the region range from about 660 m in the Snake River Plains and adjoining Owyhee Uplands to 2522 m at Hayden Peak in the Owyhee Mountains. Where the Snake River Plain area is mostly sediment-covered basalt, the area south of the Snake River known as the Owyhee Uplands, includes rolling hills, sharply dissected by basaltic plateaus. The Owyhee Mountains have a complex geology, with steep slopes of both basalt and granite. In the northern areas of the Owyhee Mountains, the steep hills, mountains, and escarpments consist of basalt. In other areas of the mountains the steep slopes are of granitic or rhyolitic origin. The mountains are surrounded by broad expanses of sagebrush covered plateaus. The soils of the Snake River Plains are generally non-calcareous and alkaline. Most are well-drained, with common soil textures of silt loam, loam and fine sand loam. In the Uplands and Mountains, the soils are often coarse textured on the surface, while the subsoils are loamy and non-calcareous. -

Reviewing the Taxonomy of Podaxis: Opportunities for Understanding Extreme Fungal Lifestyles

Fungal Biology 123 (2019) 183e187 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Fungal Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/funbio Review Reviewing the taxonomy of Podaxis: Opportunities for understanding extreme fungal lifestyles * Benjamin H. Conlon a, , Duur K. Aanen b, Christine Beemelmanns c, Z. Wilhelm de Beer d, Henrik H. De Fine Licht e, Nina Gunde-Cimerman f, Morten Schiøtt a, Michael Poulsen a a Section for Ecology and Evolution, Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark b Laboratory of Genetics, Plant Sciences Group, Wageningen University, Netherlands c Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology, Hans-Knoll-Institute,€ Chemical Biology, Jena, Germany d Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI), University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa e Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark f Department of Biology, Biotechnical Faculty, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia article info abstract Article history: There are few environments more hostile and species-poor than deserts and the mounds of Nasuti- Received 27 August 2018 termitinae termites. However, despite the very different adaptations required to survive in such extreme Received in revised form and different environments, the fungal genus Podaxis is capable of surviving in both: where few other 13 December 2018 fungi are reported to grow. Despite their prominence in the landscape and their frequent documentation Accepted 8 January 2019 by early explorers, there has been relatively little research into the genus. Originally described by Available online 11 January 2019 Linnaeus in 1771, in the early 20th Century, the then ~25 species of Podaxis were almost entirely reduced Corresponding Editor: Ursula Peintner into one species: Podaxis pistillaris. -

Comparison of Two Schizophyllum Commune Strains in Production of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors and Antioxidants from Submerged Cultivation

Journal of Fungi Article Comparison of Two Schizophyllum commune Strains in Production of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors and Antioxidants from Submerged Cultivation Jovana Miškovi´c 1,†, Maja Karaman 1,*,†, Milena Rašeta 2, Nenad Krsmanovi´c 1, Sanja Berežni 2, Dragica Jakovljevi´c 3, Federica Piattoni 4, Alessandra Zambonelli 5 , Maria Letizia Gargano 6 and Giuseppe Venturella 7 1 Department of Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Novi Sad, TrgDositejaObradovi´ca2, 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia; [email protected] (J.M.); [email protected] (N.K.) 2 Department of Chemistry, Biochemistry and Environmental Protection, Faculty of Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Trg Dositeja Obradovi´ca3, 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia; [email protected] (M.R.); [email protected] (S.B.) 3 Institute of Chemistry, Technology and Metallurgy, University of Belgrade, Njegoševa 12, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] 4 Laboratory of Genetics & Genomics of Marine Resources and Environment (GenoDream), Department Biological, Geological & Environmental Sciences (BiGeA), University of Bologna, Via S. Alberto 163, 48123 Ravenna, Italy; [email protected] 5 Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie Agroalimentari, University of Bologna, Via Fanin 46, 40127 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] 6 Department of Agricultural and Environmental Science, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Via Amendola 165/A, I-70126 Bari, Italy; [email protected] Citation: Miškovi´c,J.; Karaman, M.; 7 Department of Agricultural, Food and Forest Sciences, University of Palermo, Via delle Scienze, Bldg. 4, Rašeta, M.; Krsmanovi´c,N.; 90128 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] Berežni, S.; Jakovljevi´c,D.; Piattoni, F.; * Correspondence: [email protected] Zambonelli, A.; Gargano, M.L.; † These two authors equally contributed to the performed study.