Setting the Table for Food Security: Policy Impacts in Nunavut

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geographical Report of the Crocker Land Expedition, 1913-1917

5.083 (701) Article VL-GEOGRAPHICAL REPORT OF THE CROCKER LAND EXPEDITION, 1913-1917. BY DONALD B. MACMILLAN CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION......................................................... 379 SLEDGE TRIP ON NORTH POLAR SEA, SPRING, 1914 .......................... 384 ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATIONS-ON NORTH POLAR SEA, 1914 ................ 401 ETAH TO POLAR SEA AND RETURN-MARCH AVERAGES .............. ........ 404 WINTER AND SPRING WORK, 1915-1916 ............. ......................... 404 SPRING WORK OF 1917 .................................... ............ 418 GENERAL SUMMARY ....................................................... 434 INTRODUCTJON The following report embraces the geographical work accomplished by the Crocker Land Expedition during -four years (Summer, 19.13, to Summer, 1917) spent at Etah, NortJaGreenland. Mr. Ekblaw, who was placed in charge of the 1916 expeditin, will present a separate report. The results of the expedition, naturally, depended upon the loca tion of its headquarters. The enforced selection of Etah, North Green- land, seriously handicapped the work of the expedition from start to finish, while the. expenses of the party were more than doubled. The. first accident, the grounding of the Diana upon the coast of Labrador, was a regrettable adventure. The consequent delay, due to unloading, chartering, and reloading, resulted in such a late arrival at Etah that our plans were disarranged. It curtailed in many ways the eageimess of the men to reach their objective point at the head of Flagler Bay, te proposed site of the winter quarters. The leader and his party being but passengers upon a chartered ship was another handicap, since the captain emphatically declared that he would not steam across Smith Sound. There was but one decision to be made, namely: to land upon the North Greenland shore within striking distance of Cape Sabine. -

Akshayuk Pass, Hiking Expedition

Akshayuk Pass, Hiking Expedition Program Descriptive: Akshayuk Pass, Auyuittuq National Park Majestic towers, carved in bedrock by glaciers, shooting straight for the sun: such scenery is what Auyuittuq National Park has to offer. It is, without a doubt, one of the most awe-inspiring places on Earth. Set in the middle of the Penny Ice Cap, bisected from North to South by the Akshayuk pass, an immense valley opens inland. A trek surrounded by austere looking, barren plateaus, that will take you to two of the park’s most spectacular lookouts, Thor Peak and Mount Asgard. On your way, you will have an opportunity to see impressive rock formations dating back to the last ice age, moraines, boulder fields, and much more. During this hike, your will tread over terrain ranging from arid gravel to humid, fertile tundra, with sharp peaks and a huge glacier in the backdrop. So many images that will remain with you forever. Following a 3-hour boat ride from Qikiqtarjuaq, making our way through a maze of floating iceberg, we arrive at the park’s northern entrance, then follow, 11 days of hiking, 100 km of breathtaking scenery, to be crossed on foot. Along the way, you will have an opportunity to see impressive rock formations dating back to the last ice age, moraines, boulder fields, with spectacular views of Mount Thor and Mount Asgard. Throughout the trek, you will be mesmerized by the presence of glaciers, landscapes and mountains each more impressive than the last. Our goal, reaching the Southern entrance of the Park, where 30km of boat ride will be separating us from Pangnirtung the closest community. -

Importance of Auyuittuq National Park

Auyuittuq NATIONAL PARK OF CANADA Draft Management Plan January 2009 i Cover Photograph(s): (To be Added in Final Version of this Management Plan) National Library of Canada cataloguing in publication data: Parks Canada. Nunavut Field Unit. Auyuittuq National Park of Canada: Management Plan / Parks Canada. Issued also in French under title: Parc national du Canada Auyuittuq, plan directeur. Issued also in Inuktitut under title: ᐊᐅᔪᐃᑦᑐᖅ ᒥᕐᖑᐃᓯᕐᕕᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ ᑲᓇᑕᒥ ᐊᐅᓚᓯᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᐊᑐᖅᑕᐅᔪᒃᓴᖅ 1. Auyuittuq National Park (Nunavut)‐‐Management. 2. National parks and reserves‐‐Canada‐‐Management. 3. National parks and reserves‐‐Nunavut‐‐ Management. I. Parks Canada. Western and Northern Service Centre II. Title. FC XXXXXX 200X XXX.XXXXXXXXX C200X‐XXXXXX‐X © Her Majesty the Queen in the Right of Canada, represented by the Chief Executive Officer of Parks Canada, 200X. Paper: ISBN: XXXXXXXX Catalogue No.: XXXXXXXXX PDF: ISBN XXXXXXXXXXX Catalogue No.: XXXXXXXXXXXX Cette publication est aussi disponible en français. wktg5 wcomZoxaymuJ6 wktgotbsix3g6. i Minister’s Foreword (to be included when the Management Plan has been approved) QIA President’s Foreword (to be included when the Management Plan has been approved) NWMB Letter (to be included when the Management Plan has been approved) Recommendation Statement (to be included when the Management Plan has been approved) i Acknowledgements The preparation of this plan involved many people. The input of this diverse group of individuals has resulted in a plan that will guide the management of the park for many years. -

Petitioner's Legal Representative: Paul Crowley PO Box 1630 Iqaluit, Nunavut X0A 0H0 Canada

PETITION TO THE INTER AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS SEEKING RELIEF FROM VIOLATIONS RESULTING FROM GLOBAL WARMING CAUSED BY ACTS AND OMISSIONS OF THE UNITED STATES SUBMITTED BY SHEILA WATT-CLOUTIER, WITH THE SUPPORT OF THE INUIT CIRCUMPOLAR CONFERENCE, ON BEHALF OF ALL INUIT OF THE ARCTIC REGIONS OF THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA, INCLUDING: Pitseolak Alainga, Iqaluit, Nunavut Jamesie Mike, Pangnirtung, Nunavut Heather Angnatok, Nain, Newfoundland and Labrador Meeka Mike, Iqaluit, Nunavut Evie Anilniliak, Pangnirtung, Nunavut Roy Nageak, Barrow, Alaska Louis Autut, Chesterfield Inlet, Nunavut Annie Napayok, Whale Cove, Nunavut Christine Baikie, Nain, Newfoundland and Labrador Enosilk Nashalik, Pangnirtung, Nunavut Eugene Brower, Barrow, Alaska Simon Nattaq, Iqaluit, Nunavut Ronald Brower, Barrow, Alaska Herbert Nayokpuk, Shishmaref, Alaska Johnnie Cookie, Umiujaq, Quebec George Noongwook, Savoonga, Alaska Sappa Fleming, Kuujjuarapik, Québec Peter Paneak, Clyde River, Nunavut Lizzie Gordon, Kuujjuaq, Québec Uqallak Panikpak, Clyde River, Nunavut Sandy Gordon, Kuujjuaq, Québec Joanasie Qappik, Pangnirtung, Nunavut David Haogak, Sachs Harbour, Northwest Territories Apak Qaqqasiq, Clyde River, Nunavut Edith Haogak, Sachs Harbour, Northwest Territories James Qillaq, Clyde River, Nunavut, Julius Ikkusek, Nain, Newfoundland and Labrador Paul Rookok, Savoonga, Alaska Lucas Ittulak, Nain, Newfoundland and Labrador Joshua Sala, Umiujaq, Québec Sarah Ittulak, Nain, Newfoundland and Labrador Akittiq Sanguya, Clyde River, Nunavut Willie Jooktoo, -

Auyuittuq National Park

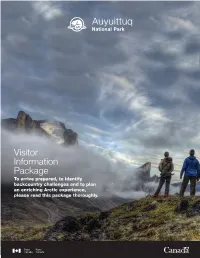

Auyuittuq National Park Visitor Information Package To arrive prepared, to identify backcountry challenges and to plan an enriching Arctic experience, please read this package thoroughly. Photo: Michael H Davies 2019 i For More Information Contact our Park Offices in Pangnirtung or Qikiqtarjuaq, or visit our website. Pangnirtung Office Qikiqtarjuaq Office Phone: (867) 473-2500 Phone: (867) 927-8834 Fax: (867) 473-8612 Fax: (867) 927-8454 [email protected] [email protected] Hours of Operation Season of Operation September through June Mid-March through mid-September: Monday to Friday, 8:30 a.m. - 12 noon, 1 p.m. - 5 p.m. Hours are variable. Call in advance to arrange Closed weekends orientation times. April, July and August Closed late September through early March Open 7 days a week, 8:30 a.m. - 12 noon, 1 p.m. - 5 p.m. parkscanada.gc.ca/auyuittuq Related Websites Auyuittuq National Park website: parkscanada.gc.ca/auyuittuq Nunavut Tourism: www.nunavuttourism.com Mirnguiqsirviit – Nunavut Territorial Parks: www.nunavutparks.com Weather Conditions Pangnirtung: www.weatheroffice.gc.ca/city/pages/nu-7_metric_e.html Qikiqtarjuaq: www.weatheroffice.gc.ca/city/pages/nu-5_metric_e.html Transport Canada: www.tc.gc.ca Pangnirtung Tide charts: www.waterlevels.gc.ca What kind of explorer are you? Find out how to maximize your Canadian travel experience by visiting www.caen. canada.travel/traveller-types All photos copyright Parks Canada unless otherwise stated ii 2019 Table of Contents Welcome v Important Information 1 Pre-Trip, Post-Trip, -

Qikiqtani Inuit Association 2010

QTC Interview and Testimony Summaries Qikiqtani Inuit Association 2010 NOTICE TO READER This document was submitted 20 October 2010 at the Board Meeting of the Qikiqtani Inuit Association. Qikiqtani Inuit Association P.O. Box 1340 Iqaluit, NU X0A 0H0 Phone: (867) 975-8400 Fax: (867) 979-3238 The preparation of this document was completed under the direction of: Madeleine Redfern Executive Director, Qikiqtani Truth Commission P.O. Box 1340 Iqaluit, NU X0A 0H0 Tel: (867) 975-8426 Fax: (867) 979-1217 Email: [email protected] Table of Contents: Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 1 QIA interviews .......................................................................................................................................... 1 QTC interviews ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Photos ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Arctic Bay ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Qikiqtani Inuit Association .................................................................................................................. -

Visitor Information Package to Arrive Prepared, to Identify Backcountry Challenges and to Plan an Enriching Arctic Experience, Please Read This Package Thoroughly

Visitor Information Package To arrive prepared, to identify backcountry challenges and to plan an enriching Arctic experience, please read this package thoroughly. 2019 For more information Contact our Park Offices in Pangnirtung or Qikiqtarjuaq, or visitwww.pc.gc.ca/auyuittuq . Pangnirtung office Qikiqtarjuaq office Phone: 867-473-2500 Phone: 867-927-8834 Fax: 867-473-8612 Fax: 867-927-84542 [email protected] [email protected] Hours of Operation Hours of Operation September through June Mid-March through mid-September: Monday to Friday, 8:30 a.m. - 12 noon, 1 p.m. - 5 p.m. Hours are variable. Call in advance to arrange orientation times. Closed weekends April, July and August Closed late September through early March Open 7 days a week, 8:30 a.m. - 12 noon, 1 p.m. - 5 p.m. Related websites Additional Resources: www.pc.gc.ca/auyuittuq Mirnguiqsirviit – Nunavut Territorial Parks: www.nunavutparks.com Nunavut Tourism: www.nunavuttourism.com Transport Canada: www.tc.gc.ca Pangnirtung tide charts: www.waterlevels.gc.ca Weather Conditions: Pangnirtung: www.weatheroffice.gc.ca/city/pages/nu-7_metric_e.html Qikiqtarjuaq: www.weatheroffice.gc.ca/city/pages/nu-5_metric_e.html All photos copyright Parks Canada unless otherwise stated. 2019 Table of contents Welcome 2 Important information 3 - 4 Pre-trip and post-trip 3 Registration, de-registration and permits 4 Planning your trip 5 Auyuittuq National Park map 5 Topographical maps 5 How to get here 6 Air access to Nunavut 6 Emergency medical travel 6 Travelling -

Laura Churchill

ᑐᓴᕋᔅᓴᑦ TUSARASSAT Fall 2019 TALLURUTIUP IMANGA AND TUVAIJUITTUQ ANNOUNCEMENTS GOVERNMENT OF CANADA APOLOGIZES TO QIKIQTANI INUIT MARY RIVER ANNUAL PROJECT REVIEW FORUM WWW.QIA.CA [email protected] @Qikiqtanilnuit @Qikiqtani_Inuit @Qikiqtani_Inuit COMMUNITY WHAT’S IN THIS ISSUE HARBOURS IN Tallurutiup Imanga and Tuvaijuittuq Announcements .................................................. 3 GRISE FIORD AND Tallurutiup Imanga and Tuvaijuittuq Feast in Arctic Bay.............................................. 4 RESOLUTE BAY Government of Canada apologizes to Qikiqtani Inuit ................................................ 6 QIA President, P.J. Akeeagok welcomed Minister of Transport QIA board meeting in Qikiqtarjuaq ..........10 Canada Marc Garneau to Iqaluit, on August 14, to share Mary River Annual Project more details about the community harbours in Grise Fiord Review Forum ....................................................12 and Resolute Bay. These investments were announced in early August by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau under the A visit to the Mary River mine .....................13 Tallurutiup Imanga and Tuvaijuittuq Agreements. Transport Profile: Laura Churchill ..................................14 Canada is providing $76.5 million over seven years towards Inuktitut early childhood resources the project, as part of a $190 million fund for infrastructure in distributed across Nunavut ..........................16 the Tallurutiup Imanga communities. Update on the Community Based Monitoring pilot project in Pond Inlet .....17 Rising above -

Inuit Modern: Art from the Samuel and Esther Sarick Collection, Edited By

254 • REVIEWS Schwarzenbach’s diary begins with the May 8, 1953, When they returned to base camp in the early morning arrival of the expedition participants in Montreal. The fol- hours of July 14, they heard disturbing news from Pat Baird: lowing days were spent assembling and packing the expe- Ben Battle, the McGill University geomorphologist, was miss- dition supplies and gear in the front yard of the Arctic ing. Following tracks in the snow and ice and knowing the area Institute headquarters at McGill University. By May 12, of Ben’s scientific investigations, the expedition members con- everything was ready and 4000 lbs of gear were transported centrated their efforts on a lake with newly broken ice. On July to Frobisher Bay (now Iqaluit) courtesy of the Royal Cana- 15, they recovered Ben Battle’s body. They buried him in a dian Air Force. A year earlier, 13 tons of expedition sup- stone grave and erected a large stone cairn nearby. plies had been shipped to Pangnirtung by sea. From Iqaluit, Zoological work was carried out from the biologi- men and gear were flown to Pangnirtung in a Norseman cal camp on the Owl River, which drains the northern aircraft, chartered from Arctic Wings of Churchill, Mani- part of Pangnirtung Pass. Having spent four weeks assist- toba. The first of the four flights that landed on the sea ice ing with the seismic work, the author joined McGill Uni- below the hamlet was met by a large number of inquisitive versity zoologist Adam Watson on the Owl River, where Inuit. -

Building Capacity in Arctic Societies: Dynamics and Shifting Perspectives

International Ph.D. School for Studies of Arctic Societies (IPSSAS) Building Capacity in Arctic Societies: Dynamics and Shifting Perspectives Proceedings of the Second IPSSAS seminar Iqaluit, Nunavut, Canada May 26 to June 6, 2003 Edited by: François Trudel CIÉRA Faculté des sciences sociales Université Laval, Québec, Canada IPSSAS expresses its gratitude to the following institutions and departments for financially supporting or hosting the Second IPSSAS seminar in Iqaluit, Nunavut, Canada, in 2003: - Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade / Ministère des Affaires extérieures et du Commerce international du Canada - Nunavut Arctic College (Nunatta Campus) - Nunavut Research Institute - Université Laval – Vice-rectorat à la recherche and CIÉRA - Ilisimatusarfik/University of Greenland - Research Bureau of Greenland's Home Rule - The Commission for Scientific Research in Greenland (KVUG) - National Science Foundation through the Arctic Research Consortium of the United States - Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales (INALCO), Paris, France - Ministère des Affaires étrangères de France - University of Copenhagen, Denmark The publication of these Proceedings has been possible through a contribution from the CANADIAN POLAR COMMISSION / COMMISSION CANADIENNE DES AFFAIRES POLAIRES Source of cover photo: IPSSAS Website International Ph.D. School for Studies of Arctic Societies (IPSSAS) Building Capacity in Arctic Societies: Dynamics and Shifting Perspectives Proceedings of the 2nd IPSSAS seminar, Iqaluit, -

Éducation Et Transmission Des Savoirs Inuit Au Canada »

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Érudit Article « Éducation et transmission des savoirs inuit au Canada » Frédéric Laugrand et Jarich Oosten Études/Inuit/Studies, vol. 33, n°1-2, 2009, p. 7-34. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/044957ar DOI: 10.7202/044957ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 13 février 2017 09:32 Éducation et transmission des savoirs inuit au Canada Sous la direction de: Frédéric Laugrand* et Jarich Oosten** Il est temps qu’on reconnaisse à l’Esquimau ce qu’on a appelé le «droit d’être différent». Et ce droit ne sera vraiment reconnu que lorsque l’Esquimau aura son école à lui et sera instruit, dans la mesure du possible, dans sa propre langue (Mary-Rousselière 1963: 8). Lorsque les étudiants se posent des questions sur qui ils sont présentement et où ils se dirigent, c’est grâce aux récits de vie des aînés qu’ils peuvent trouver un sens à leur culture et à eux-mêmes en tant qu’Inuit vivant dans le présent (Annahatak 1994: 17)1. -

Traditional Inuit Stories by Noel K. Mcdermott a Thesis

Unikkaaqtuat: Traditional Inuit Stories By Noel K. McDermott A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Cultural Studies in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada April, 2015 Copyright © Noel McDermott, 2015 Abstract Commentary on Inuit language, culture and traditions, has a long history, stretching at least as far back as 1576 when Martin Frobisher encountered Inuit on the southern shores of Baffin Island. The overwhelming majority of this vast collection of observations has been made by non-Inuit, many of whom spent limited time getting acquainted with the customs and history of their objects of study. It is not surprising, therefore, that the lack of Inuit voice in all this literature, raises serious questions about the credibility of the descriptions and the validity of the information. The Unikkaaqtuat: Traditional Inuit Stories project is presented in complete opposition to this trend and endeavours to foreground the stories, opinions and beliefs of Inuit, as told by them. The unikkaaqtuat were recorded and translated by professional Inuit translators over a five day period before an audience of Inuit students at Nunavut Arctic College, Iqaluit, Nunavut in October 2001. Eight Inuit elders from five different Nunavut communities told stories, discussed possible meanings and offered reflections on a broad range of Inuit customs and beliefs. What emerges, therefore, is not only a collection of stories, but also, a substantial body of knowledge about Inuit by Inuit, without the intervention of other voices. Editorial commentary is intentionally confined to correction of spellings and redundant repetitions.