Inuit Perceptions of Modern Guideposts (Nutaaq Inuksuit) That Will Help Students Stay in High School Karen Tyler University of Vermont

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

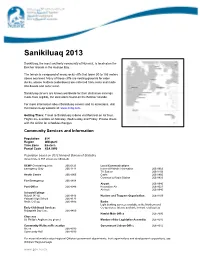

Sanikiluaq 2013

Sanikiluaq 2013 Sanikiluaq, the most southerly community of Nunavut, is located on the Belcher Islands in the Hudson Bay. The terrain is composed of many rocky cliffs that tower 50 to 155 meters above sea level. Many of these cliffs are nesting grounds for eider ducks, whose feathers (eiderdown) are collected from nests and made into duvets and outer-wear. Sanikiluaq carvers are known worldwide for their distinctive carvings made from argillite, the dark stone found on the Belcher Islands. For more information about Sanikiluaq carvers and its attractions, visit their local co-op website at: www.mitiq.com. Getting There: Travel to Sanikiluaq is done via Montreal on Air Inuit. Flights are available on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Please check with the airline for schedule changes. Community Services and Information Population 854 Region Qikiqtani Time Zone Eastern Postal Code X0A 0W0 Population based on 2012 Nunavut Bureau of Statistics (Area Code is 867 unless as indicated) RCMP General Inquiries 266-0123 Local Communications Emergency Only 266-1111 Internet/Website information 266-8963 TV Station 266-8156 Health Centre 266-8965 Cable 266-8860 Community Radio Station 266-8833 Fire Emergency 266-8888 Airport 266-8946 Post Office 266-8945 Keewaiten Air 266-8021 Air Inuit 266-8946 Schools/College Nuiyak (K-12) 266-8816 Hunters and Trappers Organization 266-8709 Patsaali High School 266-8173 Arctic College 266-8885 Banks Light banking services available at the Northern and Early Childhood Services Co-op stores; Interac available in most retail outlets Najuqsivik Day Care 266-8400 Hamlet Main Office 266-7900 Churches St. -

Inunnguiniq: Caring for Children the Inuit Way

Inuit CHILD & YOUTH HEALTH INUNNGUINIQ: CARING FOR CHILDREN THE INUIT WAY At the heart and soul of Inuit culture are our values, language, and spirit. These made up our identity and enabled us to survive and flourish in the harsh Arctic environment. In the past, we did not put a word to this; it was within us and we knew it instinctively. Then, we were alone in the Arctic but now, in two generations, we have become part of the greater Canadian and world society. We now call the values, language, and spirit of the past Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit. (Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, 2000) Prepared by Shirley Tagalik, Educational it. Inunnguiniq is literally translated as “the thinking, and behaviour. The specific Consultant, Inukpaujaq Consulting making of a human being.” The cultural process for ensuring this result— expectation is that every child will become inunnguiniq—is a shared responsibility Defining Inunnguiniq able/enabled/capable so that they can be within the group. Inunnguiniq is the Inuit assured of living a good life. A good life is equivalent of “it takes a village to raise a Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) describes considered one where you have sufficient child.” Inherent in the process are a set of Inuit worldview.1 It is a holistic way of proper attitude and ability to be able to role expectations for those connected with being interconnected in the world and contribute to working for the common a child to nurture, protect, observe, and is based in four big laws or maligait. good—helping others and making create a path in life that is uniquely fitted These include working for the common improvements for those to come. -

Cosmology and Shamanism and Shamanism INTERVIEWING INUIT ELDERS

6507.3 Eng Cover w/spine/bleed 5/1/06 9:23 AM Page 1 INTERVIEWINGCosmology INUIT ELDERS and Shamanism Cosmology and Shamanism INTERVIEWING INUIT ELDERS Mariano and Tulimaaq Aupilaarjuk, Lucassie Nutaraaluk, Rose Iqallijuq, Johanasi Ujarak, Isidore Ijituuq and Michel Kupaaq 4 Edited by Bernard Saladin d’Anglure 6507.5_Fre 5/1/06 9:11 AM Page 239 6507.3 English Vol.4 5/1/06 9:21 AM Page 1 INTERVIEWING INUIT ELDERS Volume 4 Cosmology and Shamanism Mariano and Tulimaaq Aupilaarjuk, Lucassie Nutaraaluk, Rose Iqallijuq, Johanasi Ujarak, Isidore Ijituuq and Michel Kupaaq Edited by Bernard Saladin d’Anglure 6507.3 English Vol.4 5/1/06 9:21 AM Page 2 Interviewing Inuit Elders Volume 4 Cosmology and Shamanism Copyright © 2001 Nunavut Arctic College, Mariano and Tulimaaq Aupilaarjuk, Bernard Saladin d’Anglure and participating students Susan Enuaraq, Aaju Peter, Bernice Kootoo, Nancy Kisa, Julia Saimayuq, Jeannie Shaimayuk, Mathieu Boki, Kim Kangok, Vera Arnatsiaq, Myna Ishulutak, and Johnny Kopak. Photos courtesy Bernard Saladin d’Anglure; Frédéric Laugrand; Alexina Kublu; Mystic Seaport Museum. Louise Ujarak; John MacDonald; Bryan Alexander. Illustrations courtesy Terry Ryan in Blodgett, ed. “North Baffin Drawings,” Art Gallery of Ontario; 1923 photo of Urulu, Fifth Thule Expedition. Cover illustration “Man and Animals” by Lydia Jaypoody. Design and production by Nortext (Iqaluit). All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without written consent of the publisher is an infringement of the copyright law. ISBN 1-896-204-384 Published by the Language and Culture Program of Nunavut Arctic College, Iqaluit, Nunavut with the generous support of the Pairijait Tigummivik Elders Society. -

Evangelical and Aboriginal Christianity on Baffin Island: a Case Study of Pond Inlet (Mittimatalik), 1929-1934

1 Evangelical and Aboriginal Christianity on Baffin Island: A Case Study of Pond Inlet (Mittimatalik), 1929-1934 C.M. Sawchuk Trinity Hall Thesis submitted in completion of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Polar Studies Scott Polar Research Institute/Department of Geography University of Cambridge June 2006 2 Preface I hereby declare that my dissertation, entitled Evangelical and Aboriginal Christianity on Baffin Island: A Case Study of Pond Inlet (Mittimatalik), 1929-1934, is not the same as any I have submitted for any other degree, diploma, or similar qualification at any university or similar institution. I also declare that no part of my dissertation has already been or is concurrently being submitted for any such degree, diploma, or similar qualification. I declare that this dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. Finally, I declare that this dissertation does not exceed the 20,000 words, excluding footnotes, appendices, and references, that has been approved by the Board of Graduate Studies for the MPhil in Polar Studies. _________________________________________ Christina M. Sawchuk 3 Acknowledgements No man is an island entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. (John Donne) The process of researching and writing a dissertation is akin to being stranded on a desert isle, in that very few others can truly understand the parameters of the intellectual, physical, and mental ordeal. I wish to thank the people who have provided bridges to the mainland, as it were, in all these matters. -

Social Hierarchy and Societal Roles Among the Inuit People by Caitlin Amborski and Erin Miller

Social Hierarchy and Societal Roles among the Inuit People by Caitlin Amborski and Erin Miller Markers of social hierarchy are apparent in four main aspects of traditional Inuit culture: the community as a whole, leadership, gender and marital relationships, and the relationship between the Inuit and the peoples of Canada. Due to its presence in multiple areas of Inuit everyday life, the theme of social hierarchy is also clearly expressed in Inuit artwork, particularly in the prints from Kinngait Studios of Cape Dorset and in sculptures. The composition of power in Inuit society is complex, since it is evident on multiple levels within Inuit culture.1 The Inuit hold their traditions very highly. As a result, elders play a crucial role within the Inuit community, since they are thought to be the best source of knowledge of the practices and teachings that govern their society. Their importance is illustrated by Kenojuak Ashevak’s print entitled Wisdom of the Elders, which she devotes to this subject.2 She depicts a face wearing a hood from a traditional Inuit jacket in the center of the composition with what appears to be a yellow aura, and contrasting red and green branches radiating from the hood. Generally, the oldest family members are looked upon as elders because their age is believed to reveal the amount of wisdom that they hold.3 One gets the sense that the person portrayed in this print is an elder, based on the wrinkles that are present around the mouth. In Inuit society, men and women alike are recognized as elders, and this beardless face would seem 1 Janet Mancini Billson and Kyra Mancini, Inuit Women: their powerful spirit in a century of change, (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), 56. -

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit Education Framework

4 Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit Education Framework ISBN 1-55015-031-5 Published by the Nunavut Department of Education, Curriculum and School Services Division All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without written consent of the publisher, is an infringement of copyright law. © 2007 Nunavut Department of Education Cover and title pages Graphix Design Studio, Ottawa Illustrations by Donald Uluadluak Sr. and Gwen Frankton © Nunavut Department of Education Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit Education Framework 5 Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit Education Framework It is critical to read this document to understand the Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) perspectives that are changing curriculum, learning and teaching in Nunavut schools. Curriculum in Nunavut is different because Inuit perspectives inform the basic elements of curriculum. The Department of Education expects educators to develop an understanding of: • Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit • how IQ affects the basic elements of curriculum • how the new basic elements of curriculum influence learning and teaching The Department expects educators to deliver instruction that reflectsInuit Qaujimajatuqangit and achieves the purposes of education in Nunavut as described in this document. As described further in the following pages, using Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit as the foundation for curriculum means that the basic elements of curriculum: • Follow a learning continuum • Incorporate four integrated strands • Introduce and teach cross-curricular competencies based on the eight Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit Principles • Include and build upon Inuit philosophies of: Inclusion Languages of Instruction Dynamic Assessment Critical Pedagogy 6 Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit Education Framework We must teach our children their mother tongue. -

Documenting Inuit Knowledge of Coastal Oceanography in Nunatsiavut

Respecting ontology: Documenting Inuit knowledge of coastal oceanography in Nunatsiavut By Breanna Bishop Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Marine Management at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia December 2019 © Breanna Bishop, 2019 Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures ............................................................................................................ iv Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ vi Chapter 1: Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Management Problem ...................................................................................................................... 4 1.1.1 Research aim and objectives ........................................................................................................................ 5 Chapter 2: Context ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Oceanographic context for Nunatsiavut ......................................................................................... 7 2.3 Inuit knowledge in Nunatsiavut decision making ......................................................................... -

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

1 Standing Committee on Legislation Hearings on Bill 25, an Act To

Standing Committee on Legislation ᒪᓕᒐᓕᕆᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᑲᑎᒪᔨᕋᓛᑦ Hearings on Bill 25, An Act to Amend the ᕿᒥᕐᕈᓂᖏᑦ ᒪᓕᒐᕐᒥᒃ ᐋᖅᑭᒋᐊᖅᑕᐅᖁᓪᓗᒍ Education Act and the Inuit Language ᐃᓕᓐᓂᐊᖅᑐᓕᕆᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᒪᓕᒐᖅ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ Protection Act ᐅᖃᐅᓯᖓ ᓴᐳᒻᒥᔭᐅᓂᖓᓄᑦ ᒪᓕᒐᖅ Iqaluit, Nunavut ᐃᖃᓗᐃᑦ, ᓄᓇᕗᑦ November 26, 2019 ᓄᕕᐱᕆ 26, 2019 Members Present: ᒪᓕᒐᓕᐅᖅᑏᑦ ᐅᐸᒃᑐᑦ: Tony Akoak ᑑᓂ ᐋᖁᐊᖅ Pat Angnakak ᐹᑦ ᐊᕐᓇᒃᑲᖅ Joelie Kaernerk ᔪᐃᓕ ᖃᐃᕐᓂᖅ Mila Kamingoak ᒦᓚ ᖃᒥᓐᖑᐊᖅ Pauloosie Keyootak ᐸᐅᓗᓯ ᕿᔪᒃᑖᖅ Adam Lightstone ᐋᑕᒻ ᓚᐃᑦᓯᑑᓐ John Main, Chair ᐋᕐᓗᒃ ᒪᐃᓐ, ᐃᒃᓯᕙᐅᑕᖅ Margaret Nakashuk ᓯᒥᐅᓐ ᒥᑭᓐᖑᐊᖅ David Qamaniq ᒫᒡᒍᓚ ᓇᑲᓱᒃ Emiliano Qirngnuq ᑕᐃᕕᑎ ᖃᒪᓂᖅ Paul Quassa ᐃᒥᓕᐊᓄ ᕿᓐᖑᖅ Allan Rumbolt ᐹᓪ ᖁᐊᓴ Cathy Towtongie, Co-Chair ᐋᓚᓐ ᕋᒻᐴᑦ ᖄᑕᓂ ᑕᐅᑐᓐᖏ, ᐃᒃᓯᕙᐅᑕᐅᖃᑕᐅᔪᖅ Staff Members: ᐃᖅᑲᓇᐃᔭᖅᑏᑦ: Michael Chandler ᒪᐃᑯᓪ ᓵᓐᑐᓗ Stephen Innuksuk ᓯᑏᕙᓐ ᐃᓄᒃᓱᒃ Siobhan Moss ᓯᕚᓐ ᒫᔅ Interpreters: ᑐᓵᔩᑦ: Lisa Ipeelee ᓖᓴ ᐊᐃᐱᓕ Andrew Dialla ᐋᓐᑐᓘ ᑎᐊᓚ Attima Hadlari ᐊᑏᒪ ᕼᐊᑦᓚᕆ Allan Maghagak ᐋᓚᓐ ᒪᒃᕼᐊᒐᒃ Philip Paneak ᐱᓕᑉ ᐸᓂᐊᖅ Blandina Tulugarjuk ᐸᓚᓐᑏᓇ ᑐᓗᒑᕐᔪᒃ Witnesses: Melissa Alexander, Manager of Planning, ᐊᐱᖅᓱᖅᑕᐅᔪᑦ: Reporting and Evaluation, Department of ᒪᓕᓴ ᐋᓕᒃᓵᓐᑐ, ᐊᐅᓚᑦᑎᔨ ᐸᕐᓇᓐᓂᕐᒧᑦ, Education ᐅᓂᒃᑳᓕᐅᕐᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᖃᐅᔨᓴᕐᓂᕐᒧᑦ, Jack Ameralik, Vice-Chairman, Gjoa Haven ᐃᓕᓐᓂᐊᖅᑐᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ District Education Authority ᔮᒃ ᐊᒥᕋᓕᒃ, ᐃᒃᓯᕙᐅᑕᐅᑉ ᑐᓪᓕᐊ, ᐅᖅᓱᖅᑑᒥ James Arreak, Interim Executive Director, ᐃᓕᓐᓂᐊᖅᑐᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ ᑲᑎᒪᔨᖏᑦ Coalition of Nunavut District Education ᔭᐃᒥᓯ ᐋᕆᐊᒃ, ᑐᑭᒧᐊᖅᑎᑦᑎᔨᒻᒪᕆᐅᑲᐃᓐᓇᖅᑐᖅ, Authorities ᑭᒡᒐᖅᑐᐃᔨᖏᑦ ᐃᓕᓐᓂᐊᖅᑐᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ ᓄᓇᕘᒥ 1 Okalik Eegeesiak, Board Member, Iqaluit ᐅᑲᓕᖅ ᐃᔨᑦᓯᐊᖅ, ᑲᑎᒪᔨᐅᖃᑕᐅᔪᖅ, ᐃᖃᓗᓐᓂ District Education Authority ᐃᓕᓐᓂᐊᖅᑐᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ ᑲᑎᒪᔨᖏᑦ John Fanjoy, President, -

Geographical Report of the Crocker Land Expedition, 1913-1917

5.083 (701) Article VL-GEOGRAPHICAL REPORT OF THE CROCKER LAND EXPEDITION, 1913-1917. BY DONALD B. MACMILLAN CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION......................................................... 379 SLEDGE TRIP ON NORTH POLAR SEA, SPRING, 1914 .......................... 384 ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATIONS-ON NORTH POLAR SEA, 1914 ................ 401 ETAH TO POLAR SEA AND RETURN-MARCH AVERAGES .............. ........ 404 WINTER AND SPRING WORK, 1915-1916 ............. ......................... 404 SPRING WORK OF 1917 .................................... ............ 418 GENERAL SUMMARY ....................................................... 434 INTRODUCTJON The following report embraces the geographical work accomplished by the Crocker Land Expedition during -four years (Summer, 19.13, to Summer, 1917) spent at Etah, NortJaGreenland. Mr. Ekblaw, who was placed in charge of the 1916 expeditin, will present a separate report. The results of the expedition, naturally, depended upon the loca tion of its headquarters. The enforced selection of Etah, North Green- land, seriously handicapped the work of the expedition from start to finish, while the. expenses of the party were more than doubled. The. first accident, the grounding of the Diana upon the coast of Labrador, was a regrettable adventure. The consequent delay, due to unloading, chartering, and reloading, resulted in such a late arrival at Etah that our plans were disarranged. It curtailed in many ways the eageimess of the men to reach their objective point at the head of Flagler Bay, te proposed site of the winter quarters. The leader and his party being but passengers upon a chartered ship was another handicap, since the captain emphatically declared that he would not steam across Smith Sound. There was but one decision to be made, namely: to land upon the North Greenland shore within striking distance of Cape Sabine. -

A Path Forward: Toward Respectful Governance of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Data Housed at CIHI, Updated August 2020

A Path Forward Toward Respectful Governance of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Data Housed at CIHI Updated August 2020 We acknowledge and respect the land on which CIHI offices are located. Ottawa is the traditional unceded territory of the Algonquin nation and Toronto is the traditional territory of the Wendat, the Anishinabek Nation, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and the Treaty land and territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit. We acknowledge with respect the traditional territory of the Kanien’kehá:ka, where our Montréal office is located. In Victoria, we acknowledge with respect the traditional territory of the Songhees, Esquimalt and W̱ SÁNEĆ peoples, whose historical relationships with the land continue to this day. We recognize that these lands are home to many diverse First Nations, Inuit and Métis and we embrace the opportunity to work more closely together. All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be reproduced unaltered, in whole or in part and by any means, solely for non-commercial purposes, provided that the Canadian Institute for Health Information is properly and fully acknowledged as the copyright owner. Any reproduction or use of this publication or its contents for any commercial purpose requires the prior written authorization of the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Reproduction or use that suggests endorsement by, or affiliation with, the Canadian Institute for Health Information is prohibited. For permission or information, please contact CIHI: Canadian Institute for Health Information 495 Richmond Road, Suite 600 Ottawa, Ontario K2A 4H6 Phone: 613-241-7860 Fax: 613-241-8120 cihi.ca [email protected] © 2020 Canadian Institute for Health Information How to cite this document: Canadian Institute for Health Information. -

March 9, 2021

NUNAVUT HANSARD UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT TUESDAY, MARCH 9, 2021 IQALUIT, NUNAVUT Hansard is not a verbatim transcript of the debates of the House. It is a transcript in extenso. In the case of repetition or for a number of other reasons, such as more specific identification, it is acceptable to make changes so that anyone reading Hansard will get the meaning of what was said. Those who edit Hansard have an obligation to make a sentence more readable since there is a difference between the spoken and the written word. Debates, September 20, 1983, p. 27299. Beauchesne’s 6th edition, citation 55 Corrections: PLEASE RETURN ANY CORRECTIONS TO THE CLERK OR DEPUTY CLERK Legislative Assembly of Nunavut Speaker Hon. Paul Quassa (Aggu) Hon. David Akeeagok Joelie Kaernerk David Qamaniq (Quttiktuq) (Amittuq) (Tununiq) Deputy Premier; Minister of Economic Development and Transportation; Minister Pauloosie Keyootak Emiliano Qirngnuq of Human Resources (Uqqummiut) (Netsilik) Tony Akoak Hon. Lorne Kusugak Allan Rumbolt (Gjoa Haven) (Rankin Inlet South) (Hudson Bay) Deputy Chair, Committee of the Whole Minister of Health; Minister Deputy Speaker and Chair of the responsible for Seniors; Minister Committee of the Whole Pat Angnakak responsible for Suicide Prevention (Iqaluit-Niaqunnguu) Hon. Joe Savikataaq Deputy Chair, Committee of the Whole Adam Lightstone (Arviat South) (Iqaluit-Manirajak) Premier; Minister of Executive and Hon. Jeannie Ehaloak Intergovernmental Affairs; Minister of (Cambridge Bay) John Main Energy; Minister of Environment; Minister of Community and Government (Arviat North-Whale Cove) Minister responsible for Immigration; Services; Minister responsible for the Qulliq Minister responsible for Indigenous Hon. Margaret Nakashuk Energy Corporation Affairs; Minister responsible for the (Pangnirtung) Minister of Culture and Heritage; Utility Rates Review Council Hon.