Requirement of Zinc Transporter ZIP10 for Epidermal Development: Implication of the ZIP10–P63 Axis in Epithelial Homeostasis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Significance of the Evolutionary Relationship of Prion Proteins and ZIP Transporters in Health and Disease

The Significance of the Evolutionary Relationship of Prion Proteins and ZIP Transporters in Health and Disease by Sepehr Ehsani A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology University of Toronto © Copyright by Sepehr Ehsani 2012 The Significance of the Evolutionary Relationship of Prion Proteins and ZIP Transporters in Health and Disease Sepehr Ehsani Doctor of Philosophy Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology University of Toronto 2012 Abstract The cellular prion protein (PrPC) is unique amongst mammalian proteins in that it not only has the capacity to aggregate (in the form of scrapie PrP; PrPSc) and cause neuronal degeneration, but can also act as an independent vector for the transmission of disease from one individual to another of the same or, in some instances, other species. Since the discovery of PrPC nearly thirty years ago, two salient questions have remained largely unanswered, namely, (i) what is the normal function of the cellular protein in the central nervous system, and (ii) what is/are the factor(s) involved in the misfolding of PrPC into PrPSc? To shed light on aspects of these questions, we undertook a discovery-based interactome investigation of PrPC in mouse neuroblastoma cells (Chapter 2), and among the candidate interactors, identified two members of the ZIP family of zinc transporters (ZIP6 and ZIP10) as possessing a PrP-like domain. Detailed analyses revealed that the LIV-1 subfamily of ZIP transporters (to which ZIPs 6 and 10 belong) are in fact the evolutionary ancestors of prions (Chapter 3). -

Loss of the Dermis Zinc Transporter ZIP13 Promotes the Mildness Of

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Loss of the dermis zinc transporter ZIP13 promotes the mildness of fbrosarcoma by inhibiting autophagy Mi-Gi Lee1,8, Min-Ah Choi2,8, Sehyun Chae3,8, Mi-Ae Kang4, Hantae Jo4, Jin-myoung Baek4, Kyu-Ree In4, Hyein Park4, Hyojin Heo4, Dongmin Jang5, Sofa Brito4, Sung Tae Kim6, Dae-Ok Kim 1,7, Jong-Soo Lee4, Jae-Ryong Kim2* & Bum-Ho Bin 4* Fibrosarcoma is a skin tumor that is frequently observed in humans, dogs, and cats. Despite unsightly appearance, studies on fbrosarcoma have not signifcantly progressed, due to a relatively mild tumor severity and a lower incidence than that of other epithelial tumors. Here, we focused on the role of a recently-found dermis zinc transporter, ZIP13, in fbrosarcoma progression. We generated two transformed cell lines from wild-type and ZIP13-KO mice-derived dermal fbroblasts by stably expressing the Simian Virus (SV) 40-T antigen. The ZIP13−/− cell line exhibited an impairment in autophagy, followed by hypersensitivity to nutrient defciency. The autophagy impairment in the ZIP13−/− cell line was due to the low expression of LC3 gene and protein, and was restored by the DNA demethylating agent, 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5-aza) treatment. Moreover, the DNA methyltransferase activity was signifcantly increased in the ZIP13−/− cell line, indicating the disturbance of epigenetic regulations. Autophagy inhibitors efectively inhibited the growth of fbrosarcoma with relatively minor damages to normal cells in xenograft assay. Our data show that proper control over autophagy and zinc homeostasis could allow for the development of a new therapeutic strategy to treat fbrosarcoma. -

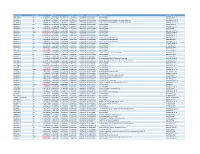

Protein Identities in Evs Isolated from U87-MG GBM Cells As Determined by NG LC-MS/MS

Protein identities in EVs isolated from U87-MG GBM cells as determined by NG LC-MS/MS. No. Accession Description Σ Coverage Σ# Proteins Σ# Unique Peptides Σ# Peptides Σ# PSMs # AAs MW [kDa] calc. pI 1 A8MS94 Putative golgin subfamily A member 2-like protein 5 OS=Homo sapiens PE=5 SV=2 - [GG2L5_HUMAN] 100 1 1 7 88 110 12,03704523 5,681152344 2 P60660 Myosin light polypeptide 6 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MYL6 PE=1 SV=2 - [MYL6_HUMAN] 100 3 5 17 173 151 16,91913397 4,652832031 3 Q6ZYL4 General transcription factor IIH subunit 5 OS=Homo sapiens GN=GTF2H5 PE=1 SV=1 - [TF2H5_HUMAN] 98,59 1 1 4 13 71 8,048185945 4,652832031 4 P60709 Actin, cytoplasmic 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=ACTB PE=1 SV=1 - [ACTB_HUMAN] 97,6 5 5 35 917 375 41,70973209 5,478027344 5 P13489 Ribonuclease inhibitor OS=Homo sapiens GN=RNH1 PE=1 SV=2 - [RINI_HUMAN] 96,75 1 12 37 173 461 49,94108966 4,817871094 6 P09382 Galectin-1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=LGALS1 PE=1 SV=2 - [LEG1_HUMAN] 96,3 1 7 14 283 135 14,70620005 5,503417969 7 P60174 Triosephosphate isomerase OS=Homo sapiens GN=TPI1 PE=1 SV=3 - [TPIS_HUMAN] 95,1 3 16 25 375 286 30,77169764 5,922363281 8 P04406 Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase OS=Homo sapiens GN=GAPDH PE=1 SV=3 - [G3P_HUMAN] 94,63 2 13 31 509 335 36,03039959 8,455566406 9 Q15185 Prostaglandin E synthase 3 OS=Homo sapiens GN=PTGES3 PE=1 SV=1 - [TEBP_HUMAN] 93,13 1 5 12 74 160 18,68541938 4,538574219 10 P09417 Dihydropteridine reductase OS=Homo sapiens GN=QDPR PE=1 SV=2 - [DHPR_HUMAN] 93,03 1 1 17 69 244 25,77302971 7,371582031 11 P01911 HLA class II histocompatibility antigen, -

MA Identifier Upordown LFC Avgexpr T P Value P Corrected

MA_Identifier UpOrDown LFC AvgExpr t p_value p_corrected mRNA_Accession mRNA_Name AGT_Accession GD214292.1 Up 2.09674838 10.60378749 30.17940104 1.3532E-12 4.15339E-08 No Good Match No Good Match TR73477|c2_g4_i1 EB253690.1 Up 1.42056324 8.629454582 16.9400776 8.61647E-10 4.15339E-08 No Good Match No Good Match TR114624|c0_g1_i1 EB324506.1 Up 1.714877372 11.7626061 29.56600148 1.62329E-12 4.15339E-08 XM_013079935 uncharacterized LOC101862711, transcript variant X2 TR105757|c1_g1_i3 EB244298.1 Up 1.504941765 13.13555745 25.49705172 8.54949E-12 6.17912E-08 XM_005093725 uncharacterized LOC101862711, transcript variant X3 TR105757|c1_g1_i1 EB350631.1 Up 1.951725495 13.11211692 23.57801356 2.22739E-11 1.45399E-07 No Good Match No Good Match TR674|c0_g1_i1 EB250403.1 Up 2.236254197 12.79847784 21.59049993 6.28948E-11 3.48034E-07 No Good Match No Good Match TR107643|c0_g1_i1 EB229658.1 Up 1.196239323 12.26876042 18.23277846 3.64746E-10 5.66891E-07 No Good Match No Good Match CL455Contig2 EB349970.1 Up 0.915715907 13.66977042 17.25614464 6.50486E-10 8.43055E-07 No Good Match No Good Match TR112158|c9_g9_i1 EB215450.1 Down -0.779710678 9.573335222 -15.07554052 2.88601E-09 1.03781E-06 No Good Match No Good Match TR81289|c1_g1_i5 EB256532.1 Up 0.957584438 12.63905003 15.56227553 2.07024E-09 1.19669E-06 No Good Match No Good Match TR64854|c4_g1_i2 EB261386.1 Up 0.771865585 7.532393475 13.39242509 1.06221E-08 1.19669E-06 No Good Match No Good Match TR87266|c0_g1_i1 EB323709.1 Up 0.993428329 8.843840926 14.33197647 5.17673E-09 1.19669E-06 XM_013085446 -

9-Azido Analogs of Three Sialic Acid Forms for Metabolic Remodeling Of

Supporting Information 9-Azido Analogs of Three Sialic Acid Forms for Metabolic Remodeling of Cell-Surface Sialoglycans Bo Cheng,†,‡ Lu Dong,†,§ Yuntao Zhu,†,‡ Rongbing Huang,†,‡ Yuting Sun,†,‖ Qiancheng You,†,‡ Qitao Song,†,§ James C. Paton, ∇ Adrienne W. Paton,∇ and Xing Chen*,†,‡,§,⊥,# †College of Chemistry and Molecular Engineering, ‡Beijing National Laboratory for Molecular Sciences, §Peking−Tsinghua Center for Life Sciences,‖Academy for Advanced Interdisciplinary Studies, ⊥Synthetic and Functional Biomolecules Center, and #Key Laboratory of Bioorganic Chemistry and Molecular Engineering of Ministry of Education, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China ∇Research Centre for Infectious Diseases, Department of Molecular and Biomedical Science, University of Adelaide, Adelaide SA 5005, Australia Page S1 Table of Contents: Scheme S1.……………………………………………………….........……………. S3 Figure S1……………………………………………………..………..……………. S3 Figure S2……………………………………………………..………..…………… S4 Figure S3……………………………………………………..………..…………… S4 Figure S4……………………………………………………..………..…………… S5 Figure S5……………………………………………………..………..…………… S6 Figure S6……………………………………………………..………..…………….S7 Figure S7……………………………………………………..………..…………….S8 Figure S8……………………………………………………..………..…………….S9 Experimental Procedures……………………………….…........…………....S10-S27 Table S1………………………………………………..………..…………….S28-S48 Supporting Reference……………………………………………….......………...S49 Page S2 Scheme S1. Synthesis of 9AzNeu5Gc Figure S1: a, b, c, d) Representative scatter plots (FSC vs. SSC) and histograms of flow cytometry analysis -

Transcriptomic and Proteomic Profiling Provides Insight Into

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Transcriptomic and Proteomic Profiling Provides Insight into Mesangial Cell Function in IgA Nephropathy † † ‡ Peidi Liu,* Emelie Lassén,* Viji Nair, Celine C. Berthier, Miyuki Suguro, Carina Sihlbom,§ † | † Matthias Kretzler, Christer Betsholtz, ¶ Börje Haraldsson,* Wenjun Ju, Kerstin Ebefors,* and Jenny Nyström* *Department of Physiology, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, §Proteomics Core Facility at University of Gothenburg, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden; †Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine and Department of Computational Medicine and Bioinformatics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan; ‡Division of Molecular Medicine, Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute, Nagoya, Japan; |Department of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden; and ¶Integrated Cardio Metabolic Centre, Karolinska Institutet Novum, Huddinge, Sweden ABSTRACT IgA nephropathy (IgAN), the most common GN worldwide, is characterized by circulating galactose-deficient IgA (gd-IgA) that forms immune complexes. The immune complexes are deposited in the glomerular mesangium, leading to inflammation and loss of renal function, but the complete pathophysiology of the disease is not understood. Using an integrated global transcriptomic and proteomic profiling approach, we investigated the role of the mesangium in the onset and progression of IgAN. Global gene expression was investigated by microarray analysis of the glomerular compartment of renal biopsy specimens from patients with IgAN (n=19) and controls (n=22). Using curated glomerular cell type–specific genes from the published literature, we found differential expression of a much higher percentage of mesangial cell–positive standard genes than podocyte-positive standard genes in IgAN. Principal coordinate analysis of expression data revealed clear separation of patient and control samples on the basis of mesangial but not podocyte cell–positive standard genes. -

Identification of Biomarker Responses in Humans Under Experimentally Induced Zinc Depletion

IDENTIFICATION OF BIOMARKER RESPONSES IN HUMANS UNDER EXPERIMENTALLY INDUCED ZINC DEPLETION By MOON-SUHN RYU A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Moon-Suhn Ryu 2 To my parents, Ji-Chul Ryu and Soon-Young Park, and my grandmother, Jung-Seo Seo 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The achievements from the past years in my life as a doctoral student would not exist without the presence of the support and love from my family far way in South Korea. I thank my parents for their love and belief in me which have been the greatest motivation for me to pursue accomplishments and success with my best efforts. I also render my gratefulness to my younger sister, Jin-Suhn Ryu, for being the best supporter in all aspects of my life. Additionally, I thank everyone with whom I shared the moments in the lab, especially, Dr. Juan P. Liuzzi, Dr. Louis A. Lichten, Dr. Liang Guo, Dr. Shou- mei Chang, Tolunay Beker Aydemir, for their invaluable advices and help. The excitement from our findings was always the greatest motivation for me to stay in progress. I also thank Gregory Guthrie, Alyssa Maki, Luisa Rios and Vanessa Da Silva for their cheer and support, particularly, during the last year of my doctoral research. I thank Meena Shankar and the staff members at the General Clinical Research Center for their advices and assistance during the phases of study design and implementation of the dietary regimen. -

The Effect of Acid on the Dynamics of Intracellular Zinc and the Marker Expressions Of

The Effect of Acid on the Dynamics of Intracellular Zinc and the Marker Expressions of Pluripotency in Somatic Cells A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Yuli Hu April 2021 © 2021 Yuli Hu. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled The Effect of Acid on the Dynamics of Intracellular Zinc and the Marker Expressions of Pluripotency in Somatic Cells by YULI HU has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Yang V. Li Professor of Biomedical Sciences Florenz Plassmann Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract YULI HU, M.S., April 2021, Biological Sciences The Effect of Acid on the Dynamics of Intracellular Zinc and the Marker Expressions of Pluripotency in Somatic Cells Director of Thesis: Yang V. Li Microenvironmental pH is one of the factors that affect the stability of zinc- protein binding. The tight binding between zinc and proteins is favored by the basic pH, whereas acidic pH favors a loose bound, and treatment of strong acid results in the dissociation of zinc. Physiologically, the stomach uses a very acidic pH to digest food which results in a high amount of soluble zinc in the stomach. Whether or not zinc co- present with acid and the effect of zinc on the gastric lining has rarely been discussed. In my experiments, acidic treatment induced the expression of a pluripotent marker in primary cultured gastric cells. It also stimulated the release of intracellular zinc, suggesting that acidic pH supported protein expression through dynamic zinc regulation. -

Frontiersin.Org 1 April 2015 | Volume 9 | Article 123 Saunders Et Al

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 28 April 2015 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00123 Influx mechanisms in the embryonic and adult rat choroid plexus: a transcriptome study Norman R. Saunders 1*, Katarzyna M. Dziegielewska 1, Kjeld Møllgård 2, Mark D. Habgood 1, Matthew J. Wakefield 3, Helen Lindsay 4, Nathalie Stratzielle 5, Jean-Francois Ghersi-Egea 5 and Shane A. Liddelow 1, 6 1 Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia, 2 Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, 3 Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia, 4 Institute of Molecular Life Sciences, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 5 Lyon Neuroscience Research Center, INSERM U1028, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique UMR5292, Université Lyon 1, Lyon, France, 6 Department of Neurobiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA The transcriptome of embryonic and adult rat lateral ventricular choroid plexus, using a combination of RNA-Sequencing and microarray data, was analyzed by functional groups of influx transporters, particularly solute carrier (SLC) transporters. RNA-Seq Edited by: Joana A. Palha, was performed at embryonic day (E) 15 and adult with additional data obtained at University of Minho, Portugal intermediate ages from microarray analysis. The largest represented functional group Reviewed by: in the embryo was amino acid transporters (twelve) with expression levels 2–98 times Fernanda Marques, University of Minho, Portugal greater than in the adult. In contrast, in the adult only six amino acid transporters Hanspeter Herzel, were up-regulated compared to the embryo and at more modest enrichment levels Humboldt University, Germany (<5-fold enrichment above E15). -

Supporting Information a Clickable Analogue of Cerulenin As

Supporting Information A Clickable Analogue of Cerulenin as Chemical Probe to Explore Protein Palmitoylation Baohui Zheng, Shunying Zhu, and Xu Wu* Cutaneous Biology Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Building 149, 13th street, Charlestown, MA 02129, USA *Corresponding author Email: [email protected] ! General procedures All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-aldrich, Alfa Aesar, Fisher Scientific or Acros and were used as received. Azide-biotin was purchased from Click Chemistry Tools. The silica gel used in flash column chromatography was from Aldrich (Cat. 60737, pore size 60 Å, 230-400 mesh). The 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained on a Varian 500M spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported in δ ppm values downfield from tetramethylsilane and J values are reported in Hz. malonic acid O piperidine 1) PhSeCl O O 11 O 11 11 OH acetic acid 2) H2O2, 50% DMSO, 85% O NaClO, pyridine NH , H O PDC, CH Cl O 3 2 NH2 2 2 11 O 60% 11 80% 70% OH O O O NH2 11 O O 3 Scheme S1. Synthesis of cerulenin analogue 3. 1. Synthesis of cis-2, 3-Epoxy-4-oxooctadec-17-ynamide (3) malonic acid O O piperidine 1) PhSeCl 11 O OH 11 O acetic acid 11 2) H O , 50% DMSO, 85% 2 2 O NaClO, pyridine NH , H O PDC, CH Cl O 3 2 NH2 2 2 11 O 60% 11 80% 70% OH O O O NH2 11 O O 3 (E)-octadec-3-en-17-ynoic acid Piperidine (11.7 µL, 0.118 mmol) and acetic acid (6.8 µL, 0.118 mmol) were stirred for 5 min in 0.5 mL DMSO at room temperature. -

Table SI. a Total of 643 Proteins Were Identified by Tandem Mass Spectrometry in the Microvesicles/Exosomes from Patients with ABE

Table SI. A total of 643 proteins were identified by tandem mass spectrometry in the microvesicles/exosomes from patients with ABE. Accession Description Coverage PS Unique AAs Molecular Calc. pI Abundance ratio: Abundance ratio: Score Sequest no. Peptides Ms Peptides weight (kDa) Moderate/ Severe/ control HT control P01024 Complement C3 85.68851 132 228 127 1663 187.03 6.4 1.12 1.131 8141.004593 1 P0C0L5 Complement C4-B 66.80046 89 128 1 1744 192.631 7.27 2.106 1.249 4859.406727 9 P01023 Alpha-2-macroglobulin 63.83989 76 140 76 1474 163.188 6.46 1.021 0.972 5149.27648 2 P02751 Fibronectin 56.03521 87 960 87 2386 262.46 5.71 0.805 1.005 3458.332983 P02768 Serum albumin 79.31034 54 104 54 609 69.321 6.28 1.157 1.086 3705.267895 4 P08603 Complement factor H 58.4078 60 544 55 1231 139.005 6.61 1.02 0.979 1917.082723 Q9Y6R7 IgGFc-binding protein 27.71508 68 305 68 5405 571.639 5.34 1.527 1.04 981.3557811 P04114 Apolipoprotein B-100 33.66206 124 255 124 4563 515.283 7.05 1.055 1.057 753.3890735 Q12860 Contactin-1 56.87623 46 242 46 1018 113.249 5.9 0.747 0.963 816.1462975 A0A0A0M Immunoglobulin heavy 55.6391 23 124 12 399 43.884 6.96 1.206 1.104 4833.498744 S08 constant gamma 1 (Fragment) 7 P01031 Complement C5 44.98807 66 254 66 1676 188.186 6.52 1.224 1.241 804.1478994 P23142 Fibulin-1 57.32575 26 297 10 703 77.162 5.22 0.812 0.946 1110.052139 O00533 Neural cell adhesion molecule 42.88079 38 220 37 1208 134.987 5.76 0.789 0.827 804.1383946 L1-like protein B4DPQ0 cDNA FLJ54471, highly 53.82476 30 278 30 719 81.837 6.37 0.995 0.971 923.9868439 -

Understanding Mechanisms of Zinc Homeostasis in Schizosaccharomyces Pombe

Understanding mechanisms of zinc homeostasis in Schizosaccharomyces pombe DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sang‐Yong Choi The Ohio State University Nutrition Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Amanda J. Bird, Ph.D. (Advisor) Earl H. Harrison, Ph.D. Daren L. Knoell, Pharm.D. Kichoon Lee, Ph.D. Copyrighted by Sang‐Yong Choi 2015 Abstract Zinc is essential for cell growth, but can be toxic when in excess. As a consequence, intracellular zinc levels are tightly controlled by complex mechanisms that maintain zinc homeostasis in all biological creatures. In eukaryotic cells, factors that affect zinc homeostasis include zinc transporters, zinc buffering molecules, and zinc‐ regulatory factors. The levels of these factors are precisely regulated to maintain optimal intracellular zinc levels. To extend the growing literature in the roles of genes involved in zinc homeostasis, this dissertation investigates the role of the above executants in maintaining cytosolic zinc levels in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. In S. pombe, Loz1 plays a specific role in repressing gene expression when zinc is in excess. In zinc‐replete conditions, Loz1 down‐regulates zrt1, a gene encoding a high affinity zinc uptake transporter, and indirectly up‐regulates zym1 expression, a gene which encodes a zinc metallothionein. Deletion of Loz1, thus, causes constitutive zrt1 expression and low zym1 expression. In addition, cells lacking a functional loz1 gene hyperaccumulate zinc in zinc‐rich medium. In chapters 2 and 3, I take advantage of the loz1 mutation, and other yeast mutants to determine the roles of specific zinc transporters and zinc buffering molecules in maintaining zinc levels in the cytosol.