UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HIS Voice 3/2009

editorial obsah Glosář Matěj Kratochvíl 2 Sunn O))) Petr Ferenc 4 Tim Hecker Karel Veselý 5 aktuálně Vážení a milí čtenáři, Alio Die Pavel Zelinka 6 již řada čísel našeho časopisu byla věnována V pasti orientalismu Karel Veselý 8 hudbě z různých koutů světa, to aktuální v nasto- lené sérii však pokračuje jen zdánlivě. Zatímco v číslech věnovaných Polsku, Francii či Slovensku Sun City Girls Thomas Bailey 12 jsme mířili za skutečnou hudbou skutečných zemí, Orient na nejnovější obálce v sobě spojuje reálný základ a notnou dávku fantazie. Spíše než o geo- Acid Mothers Temple Petr Ferenc 15 grafickou oblast nám jde o nahlédnutí za oponu téma imaginárního Východu, oblasti, do níž si mnozí hudebníci i posluchači promítají své sny. I když První císař a dialektika Druhého Jan Chmelarčík 18 si v mnoha případech půjčují skutečné nástroje a další hudební prvky, ve vzduchu visí představa pohádkových světů. Hudební Orient má častokrát Vlastislav Matoušek Matěj Kratochvíl 22 podobně neurčitou lokaci jako říše kněze Jana, do níž mířil Baudolino, hrdina stejnojmenné knihy Umberta Eca. „Na nejzazším východě těchto krajů, Georgs Pelēcis Vítězslav Mikeš 28 oddělených od oceánu zeměmi obývanými zrůd- nými bytostmi, jimiž ostatně budeme muset také Postepilog Alfreda Šnitkeho Vítězslav Mikeš 30 projít, se nachází Pozemský ráj. (…) My se tudíž současná kompozice musíme ubírat k východu, nejdřív dorazit k Eufratu, pak k Tigridu a nakonec k řece Ganges, a potom odbočit k dolním krajům východním.“ Střet reál- Christina Kubisch Pavel Klusák 34 ného a imaginárního může mít mnoho různých podob, od dokumentární činnosti značky Sublime Frequencies přes východně-západní hudbu skla- Cuong Vu Jan Faix 38 datele Tana Duna po psychedelický rock japonské skupiny Acid Mothers Temple. -

The Nudge, Ahoribuzz and @Peace

GROOVe gUiDe . FamilY owneD and operateD since jUlY 2011 SHIT WORTH DOING tthhee nnuuddggee pie-eyed anika moa cut off your hands adds to our swear jar no longer on shaky ground 7 - 13 sept 2011 . NZ’s origiNal FREE WEEKlY STREET PRESS . ISSUe 380 . GROOVEGUiDe.Co.NZ Untitled-1 1 26/08/11 8:35 AM Going Global GG Full Page_Layout 1 23/08/11 4:00 PM Page 1 INDEPENDENT MUSIC NEW ZEALAND, THE NEW ZEALAND MUSIC COMMISSION AND MUSIC MANAGERS FORUM NZ PRESENT GOING MUSIC GLOBAL SUMMIT WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW BEFORE YOU GO If you are looking to take your music overseas, come and hear from people who are working with both new and established artists on the global stage. DELEGATES APPEARING: Natalie Judge (UK) - Matador Records UK Adam Lewis (USA) - The Planetary Group, Boston Jen Long (UK) - BBC6 New Music DJ/Programmer Graham Ashton (AUS) - Footstomp /BigSound Paul Hanly (USA) - Frenchkiss Records USA Will Larnach-Jones (AUS) - Parallel Management Dick Huey (USA) - Toolshed AUCKLAND: MONDAY 12th SEPTEMBER FREE ENTRY SEMINARS, NOON-4PM: BUSINESS LOUNGE, THE CLOUD, QUEENS WHARF RSVP ESSENTIAL TO [email protected] LIVE MUSIC SHOWCASE, 6PM-10:30PM: SHED10, QUEENS WHARF FEATURING: COLLAPSING CITIES / THE SAMI SISTERS / ZOWIE / THE VIETNAM WAR / GHOST WAVE / BANG BANG ECHE! / THE STEREO BUS / SETH HAAPU / THE TRANSISTORS / COMPUTERS WANT ME DEAD WELLINGTON: WEDNESDAY 14th SEPTEMBER FREE ENTRY SEMINARS, NOON-5PM: WHAREWAKA, WELLINGTON WATERFRONT RSVP ESSENTIAL TO [email protected] LIVE MUSIC SHOWCASE, 6PM-10:30PM: SAN FRANCISCO BATH HOUSE FEATURING: BEASTWARS / CAIRO KNIFE FIGHT / GLASS VAULTS / IVA LAMKUM / THE EVERSONS / FAMILY CACTUS PART OF THE REAL NEW ZEALAND FESTIVAL www.realnzfestival.com shit Worth announciNg Breaking news Announcements Hello Sailor will be inducted into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame at the APRA Silver Scroll golDie locks iN NZ Awards, which are taking place at the Auckland Town Hall on the 13th Dates September 2011. -

Blockade Runners: MS091

Elwin M. Eldridge Collection: Notebooks: Blockade Runners: MS091 Vessel Name Vessel Type Date Built A A. Bee Steamship A.B. Seger Steamship A.C. Gunnison Tug 1856 A.D. Vance Steamship 1862 A.H. Schultz Steamship 1850 A.J. Whitmore Towboat 1858 Abigail Steamship 1865 Ada Wilson Steamship 1865 Adela Steamship 1862 Adelaide Steamship Admiral Steamship Admiral Dupont Steamship 1847 Admiral Thatcher Steamship 1863 Agnes E. Fry Steamship 1864 Agnes Louise Steamship 1864 Agnes Mary Steamship 1864 Ailsa Ajax Steamship 1862 Alabama Steamship 1859 Albemarle Steamship Albion Steamship Alexander Oldham Steamship 1860 Alexandra Steamship Alfred Steamship 1864 Alfred Robb Steamship Alhambra Steamship 1865 Alice Steamship 1856 Alice Riggs Steamship 1862 Alice Vivian Steamship 1858 Alida Steamship 1956 Alliance Steamship 1857 Alonzo Steamship 1860 Alpha Steamship Amazon Steamship 1856 Amelia Steamship America Steamship Amy Steamship 1864 Anglia Steamship 1847 Anglo Norman Steamship Anglo Saxon Steamship Ann Steamship 1857 Anna (Flora) Steamship Anna J. Lyman Steamship 1862 Anne Steamship Annie Steamship 1864 Annie Childs Steamship 1860 Antona Steamship 1859 Antonica Steamship 1851 Arabian Steamship 1851 Arcadia Steamship Ariel Steamship Aries Steamship 1862 Arizona Steamship 1858 Armstrong Steamship 1864 Arrow Steamship 1863 Asia Steamship Atalanta Steamship Atlanta Steamship 1864 Atlantic Steamship Austin Steamship 1859 B Badger Steamship 1864 Bahama Steamship 1861 Baltic Steamship Banshee Steamship 1862 Barnett Steamship Barroso Steamship 1852 Bat Steamship -

Archiving Possibilities with the Victorian Freak Show a Dissertat

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE “Freaking” the Archive: Archiving Possibilities With the Victorian Freak Show A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Ann McKenzie Garascia September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Joseph Childers, Co-Chairperson Dr. Susan Zieger, Co-Chairperson Dr. Robb Hernández Copyright by Ann McKenzie Garascia 2017 The Dissertation of Ann McKenzie Garascia is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation has received funding through University of California Riverside’s Dissertation Year Fellowship and the University of California’s Humanities Research Institute’s Dissertation Support Grant. Thank you to the following collections for use of their materials: the Wellcome Library (University College London), Special Collections and University Archives (University of California, Riverside), James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center (San Francisco Public Library), National Portrait Gallery (London), Houghton Library (Harvard College Library), Montana Historical Society, and Evanion Collection (the British Library.) Thank you to all the members of my dissertation committee for your willingness to work on a project that initially described itself “freakish.” Dr. Hernández, thanks for your energy and sharp critical eye—and for working with a Victorianist! Dr. Zieger, thanks for your keen intellect, unflappable demeanor, and ready support every step of the process. Not least, thanks to my chair, Dr. Childers, for always pushing me to think and write creatively; if it weren’t for you and your Dickens seminar, this dissertation probably wouldn’t exist. Lastly, thank you to Bartola and Maximo, Flora and Martinus, Lalloo and Lala, and Eugen for being demanding and lively subjects. -

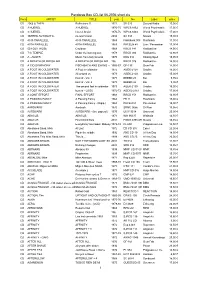

Pandoras Box CD-List 06-2006 Short

Pandoras Box CD-list 06-2006 short.xls Form ARTIST TITLE year No Label price CD 2066 & THEN Reflections !! 1971 SB 025 Second Battle 15,00 € CD 3 HUEREL 3 HUEREL 1970-75 WPC6 8462 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3 HUEREL Huerel Arisivi 1970-75 WPC6 8463 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3SPEED AUTOMATIC no man's land 2004 SA 333 Nasoni 15,00 € CD 49 th PARALLELL 49 th PARALLELL 1969 Flashback 008 Flashback 11,90 € CD 49TH PARALLEL 49TH PARALLEL 1969 PACELN 48 Lion / Pacemaker 17,90 € CD 50 FOOT HOSE Cauldron 1968 RRCD 141 Radioactive 14,90 € CD 7 th TEMPLE Under the burning sun 1978 RRCD 084 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A - AUSTR Music from holy Ground 1970 KSG 014 Kissing Spell 19,95 € CD A BREATH OF FRESH AIR A BREATH OF FRESH AIR 196 RRCD 076 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A CID SYMPHONY FISCHBACH AND EWING - (21966CD) -67 GF-135 Gear Fab 14,90 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER A Foot in coldwater 1972 AGEK-2158 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER All around us 1973 AGEK-2160 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 1 1973 BEBBD 25 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 2 1973 BEBBD 26 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER The second foot in coldwater 1973 AGEK-2159 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - (2CD) 1972-73 AGEK2-2161 Unidisc 17,90 € CD A JOINT EFFORT FINAL EFFORT 1968 RRCD 153 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy 1968 FB 11 Flashback 15,00 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy - (Digip.) 1968 PACE-034 Pacemaker 15,90 € CD AARDVARK Aardvark 1970 SRMC 0056 Si-Wan 19,95 € CD AARDVARK AARDVARK - (lim. -

Vinyls-Collection.Com Page 1/222 - Total : 8629 Vinyls Au 05/10/2021 Collection "Artistes Divers Toutes Catã©Gorie

Collection "Artistes divers toutes catégorie. TOUT FORMATS." de yvinyl Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage !!! !!! LP GSL39 Etats Unis Amerique 10cc Windows In The Jungle LP MERL 28 Royaume-Uni 10cc The Original Soundtrack LP 9102 500 France 10cc Ten Out Of 10 LP 6359 048 France 10cc Look Hear? LP 6310 507 Allemagne 10cc Live And Let Live 2LP 6641 698 Royaume-Uni 10cc How Dare You! LP 9102.501 France 10cc Deceptive Bends LP 9102 502 France 10cc Bloody Tourists LP 9102 503 France 12°5 12°5 LP BAL 13015 France 13th Floor Elevators The Psychedelic Sounds LP LIKP 003 Inconnu 13th Floor Elevators Live LP LIKP 002 Inconnu 13th Floor Elevators Easter Everywhere LP IA 5 Etats Unis Amerique 18 Karat Gold All-bumm LP UAS 29 559 1 Allemagne 20/20 20/20 LP 83898 Pays-Bas 20th Century Steel Band Yellow Bird Is Dead LP UAS 29980 France 3 Hur-el Hürel Arsivi LP 002 Inconnu 38 Special Wild Eyed Southern Boys LP 64835 Pays-Bas 38 Special W.w. Rockin' Into The Night LP 64782 Pays-Bas 38 Special Tour De Force LP SP 4971 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Strength In Numbers LP SP 5115 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Special Forces LP 64888 Pays-Bas 38 Special Special Delivery LP SP-3165 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Rock & Roll Strategy LP SP 5218 Etats Unis Amerique 45s (the) 45s CD hag 009 Inconnu A Cid Symphony Ernie Fischbach And Charles Ew...3LP AK 090/3 Italie A Euphonius Wail A Euphonius Wail LP KS-3668 Etats Unis Amerique A Foot In Coldwater Or All Around Us LP 7E-1025 Etats Unis Amerique A's (the A's) The A's LP AB 4238 Etats Unis Amerique A.b. -

The Newark Post

-...--., -- - ~ - -~. I The Newark Post PLANS DINNER PROGRAM oC ANDIDATES Newark Pitcher Twirls iFINED $200 ON ANGLERS' ASS'N No Hit, No-Run Game KIWANIS HOLDS FORP LACE ON Roland Jackson of t he Newark SECOND OFFENCE SEEKS INCREASE J uni or Hig h Schoo l baseball ANNUAL NIGHT team, ea rly in life realized t he SCHOOLBOARD I crowning ambition of every Drunken Driver Gets Heavy Newark Fishermen Will Take AT UNIVERSITY ',L baseball pitcher, when, Friday, Penalty On Second Convic- 50 New Members; Sunset S. GaJlaher Fil es For Re- I he pi tched a no-hit, no-run game against Hockessin, in the D. I. 300 Wilmington Club Mem election , !\ ll's. F. A. Wheel tion; Other T rafflc Cases Lake .Well Stocked A. A. Elementary League. To bers Have Banquet In Old ess Oppno's Him ; Election make it a real achievement, the ga me was as hard and cl ose a s Frank Eastburn was a rre ted, Mon The Newa rk Angler Association College; A. C . Wilkinson May 4. ewark Pupils Win a ba ll game can be that comes to day, by a New Cast le County Con held its first meeting of the year, last a decision in nine innings, for stabl e on a charge of dr iving while F riday night at the Farmer's Trust Arranges Program Newark won the game with a in toxicated. After hi s arrest he was Company. O. W. Widdoes, the presi lone run in the lucky seventh. taken before a physician and pro dent, presided. -

80S 697 Songs, 2 Days, 3.53 GB

80s 697 songs, 2 days, 3.53 GB Name Artist Album Year Take on Me a-ha Hunting High and Low 1985 A Woman's Got the Power A's A Woman's Got the Power 1981 The Look of Love (Part One) ABC The Lexicon of Love 1982 Poison Arrow ABC The Lexicon of Love 1982 Hells Bells AC/DC Back in Black 1980 Back in Black AC/DC Back in Black 1980 You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC Back in Black 1980 For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) AC/DC For Those About to Rock We Salute You 1981 Balls to the Wall Accept Balls to the Wall 1983 Antmusic Adam & The Ants Kings of the Wild Frontier 1980 Goody Two Shoes Adam Ant Friend or Foe 1982 Angel Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Rag Doll Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Love In An Elevator Aerosmith Pump 1989 Janie's Got A Gun Aerosmith Pump 1989 The Other Side Aerosmith Pump 1989 What It Takes Aerosmith Pump 1989 Lightning Strikes Aerosmith Rock in a Hard Place 1982 Der Komimissar After The Fire Der Komimissar 1982 Sirius/Eye in the Sky Alan Parsons Project Eye in the Sky 1982 The Stand Alarm Declaration 1983 Rain in the Summertime Alarm Eye of the Hurricane 1987 Big In Japan Alphaville Big In Japan 1984 Freeway of Love Aretha Franklin Who's Zoomin' Who? 1985 Who's Zooming Who Aretha Franklin Who's Zoomin' Who? 1985 Close (To The Edit) Art of Noise Who's Afraid of the Art of Noise? 1984 Solid Ashford & Simpson Solid 1984 Heat of the Moment Asia Asia 1982 Only Time Will Tell Asia Asia 1982 Sole Survivor Asia Asia 1982 Turn Up The Radio Autograph Sign In Please 1984 Love Shack B-52's Cosmic Thing 1989 Roam B-52's Cosmic Thing 1989 Private Idaho B-52's Wild Planet 1980 Change Babys Ignition 1982 Mr. -

It's Monk Time

Sonntag, 13. März 2016 (20:05-21:00 Uhr) KW 10 Deutschlandfunk - Musik & Information FREISTIL It’s Monk Time – Die irre Geschichte einer amerikanischen Beatband in der deutschen Provinz Von Tom Noga Redaktion: Klaus Pilger Produktion: DLF 2013 M a n u s k r i p t ACHTUNG: Die Wiederholung wurde wegen einer Sondersendung zu den Wahlen gekürzt. Dies ist das Manuskript entsprechend der Original-Länge! Urheberrechtlicher Hinweis Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt und darf vom Empfänger ausschließlich zu rein privaten Zwecken genutzt werden. Die Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder sonstige Nutzung, die über den in §§ 44a bis 63a Urheberrechtsgesetz geregelten Umfang hinausgeht, ist unzulässig. © - ggf. unkorrigiertes Exemplar - Regie Musik 1 („Blast Off “ von den Monks) startet. Darüber: O-Ton 1 Gary Burger (unübersetzt) “Monk music is original protest music. Monk music is music to make love by. Monk Music is music to relax by.” Regie Musik 1 mit dem Feedback bei 0:12 hoch ziehen. Soll bis ca 0:30 frei stehen. Darüber: Sprecher 2 Eddie Shaw (aus dem Buch „Black Monk Time“) Eines Nachts stieß Roger mich auf dem Weg von der Bühne zum Umkleideraum an. „Die beiden Typen da, die habe ich schon ein paar Mal hier gesehen.“ Ich guckte rüber. „Du meinst die beiden in den Geschäftsanzügen? Sind mir auch aufgefallen. Normale Fans sind das nicht.“ Am nächsten Abend luden uns die beiden Männer in einer Pause zwischen zwei Sets zu sich an den Tisch ein. Nachdem wir uns vorgestellt hatten, sagte der Kleinere der beiden, der mit dem blonden Raspelschnitt: „Ich bin Walther, und mein Kollege heißt Karl. -

Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1St Edition)

R O C K i n t h e R E S E R V A T I O N Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1st edition). (text, 2004) Yngvar B. Steinholt. New York and Bergen, Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. viii + 230 pages + 14 photo pages. Delivered in pdf format for printing in March 2005. ISBN 0-9701684-3-8 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt (b. 1969) currently teaches Russian Cultural History at the Department of Russian Studies, Bergen University (http://www.hf.uib.no/i/russisk/steinholt). The text is a revised and corrected version of the identically entitled doctoral thesis, publicly defended on 12. November 2004 at the Humanistics Faculty, Bergen University, in partial fulfilment of the Doctor Artium degree. Opponents were Associate Professor Finn Sivert Nielsen, Institute of Anthropology, Copenhagen University, and Professor Stan Hawkins, Institute of Musicology, Oslo University. The pagination, numbering, format, size, and page layout of the original thesis do not correspond to the present edition. Photographs by Andrei ‘Villi’ Usov ( A. Usov) are used with kind permission. Cover illustrations by Nikolai Kopeikin were made exclusively for RiR. Published by Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. 401 West End Avenue # 3B New York, NY 10024 USA Preface i Acknowledgements This study has been completed with the generous financial support of The Research Council of Norway (Norges Forskningsråd). It was conducted at the Department of Russian Studies in the friendly atmosphere of the Institute of Classical Philology, Religion and Russian Studies (IKRR), Bergen University. -

Extreme Rock from Japan

Extreme Rock From Japan Joe Paradiso MIT Media Lab Japan • Populaon = 127 million people (10’th largest) – Greater Tokyo = 30 million people (largest metro in world) – 3’rd largest GDP, 4’th largest exporter/importer • Educated, complex, and hyper mo<vated populace – OCD Paradise… • Many musicians, and the level of musicianship is high! • Japan readily absorbs western influences, but reinterprets them in its own special way… – Creavity bubbles up in crazy ways from restric<ve uniformity – Get Western idioms “wonderfully” wrong! – And does it with gusto! Nipponese Prog • Prog Rock is huge in Japan (comparavely speaking….) – And so is psych, electronica, thrash bands, Japanoise (industrial), metal, etc. • I will concentrate on Early Synth music - Symphonic Prog – Fusion/jazz - RIO (quirky) prog – Psychedelic/Space Rock – by Nature Incomplete • Ian will cover Hip Hop, Miku, etc. Early (70s) Electronics – Isao Tomta 70’s Rock Electronics - YMO • Featuring Ryuichi Sakamoto 70s Berlin-School/Floydish Rock Far East Family band • Parallel World produced by Klaus Schulze – Entering – 6:00, Saying to the Land (4:00) 70’s Progish Jazz – Stomu Yamash'ta • Supergroup “Go” • Freedom is Frightening, 5:00, Go side B Other Early 70’s Psych (Flower Travelin’ band) • Satori, pt. II, middle Early Symphonic Prog - Shingetsu 1979 • Led by Makoto Kitayama (Japanese Peter Gabriel) • Oni Early Symphonic Prog – Outer Limits (1985) 1987 2007 • The Scene Of Pale blue (Part One) – middle • Plas<c Syndrome, Consensus More Early Symphonic Prog – Mr. Sirius 1987 1990 -

FINANCING OPPORTUNITIES for EU Smes INTERNATIONALISATION in JAPAN

Uu88 Joana SANTOS VAZ FINANCING OPPORTUNITIES FOR EU SMEs INTERNATIONALISATION IN JAPAN June 2020 1 Tokyo MINERVA Report Financing Opportunities for EU SMEs internationalization in Japan DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT The information contained in this report reflects the views of the author and not necessarily the views of the EU-Japan Centre for Industrial Cooperation, nor the views of the European Commission and Japanese authorities. It does not claim to be comprehensive and is not intended to provide legal, investment, tax or other advice. While utmost care was taken to check, translate and compile all information used in this study, the author and the EU-Japan Centre for Industrial Cooperation may not be held responsible for any errors that might appear. This report is made available on the terms and understanding that the EU-Japan Centre for Industrial Cooperation and the European Commission are not responsible for the results of any actions taken on the basis of information in this report, nor for any error in or omission from this report. This report is published by the EU-Japan Centre for Industrial Cooperation. Reproduction of all the contents of the report is authorized for non- commercial purposes, provided that (i) the name of the author(s) is indicated and the EU-Japan Centre for Industrial Cooperation is acknowledged as the source, (ii) the text is not altered in any way and (iii) the attention of recipients is drawn to this warning. All other use and copying of any of the contents of this report is prohibited unless the prior, written and express consent of the EU-Japan Centre for Industrial Cooperation is obtained.