Korean Basic Course: Area Background. INSTITUTION Defense Language Inst., Washington, D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunshine in Korea

CENTER FOR ASIA PACIFIC POLICY International Programs at RAND CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Center for Asia Pacific Policy View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. The monograph/report was a product of the RAND Corporation from 1993 to 2003. RAND monograph/reports presented major research findings that addressed the challenges facing the public and private sectors. They included executive summaries, technical documentation, and synthesis pieces. Sunshine in Korea The South Korean Debate over Policies Toward North Korea Norman D. -

Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. Bennett C O R P O R A T I O N NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. -

Undermining the Global Nuclear Order? Impacts of Unilateral Negotiations Between the U.S. and North-Korea

Undermining the global nuclear order? Impacts of unilateral negotiations between the U.S. and North-Korea Gordon Friedrichs, M.A. America first – America alone? Evangelische Akademie Hofgeismar Haus der Kirche, Kassel Dienstag, 27. November 2018 Gordon Friedrichs, M.A. Evangelische Akademie Hofgeismar 24.01.2019 Haus der Kirche, Kassel #1 Outline 1. History of U.S.-North Korea relations 2. The Nuclearization of North Korea 3. North Korea and challenges to U.S. global leadership 4. Discussion: Four options for conflict resolution Chanlett-Avery et al. 2018: 3 Gordon Friedrichs, M.A. Evangelische Akademie Hofgeismar 24.01.2019 Haus der Kirche, Kassel #2 History of U.S.-North Korea relations 1949-50: Communist insurrection on Jeju Island, Soviet & Chinese military support for the North; 1910 Japanese 1948/49: Kim Il-Sung Stalin’s support for military 1937: The battle depicted becomes chairman of the invasion. rule over NK 1950-53: Korean War. in the Grand Workers’ Party of Korea; Monument in Samjiyon, Democratic People’s Samjiyon County Republic of Korea (DPRK) 38th parallel established to divide North (SU, Communist) 1949: U.S. troop and South (US) Korea withdrawal; SK instability. 1953: The Korean Armistice 1945: End of World War II; Agreement that declared cease fire but no peace on the 38th parallel; Soviet victory over Japan on 1948: Republic of Korea was Korean Peninsula consolidation of power on both sides: founded under Syngman Rhee Juche ideology paired with Stalinism (authoritarian leader) in the North; autocratic military rule in the South. Gordon Friedrichs, M.A. Evangelische Akademie Hofgeismar 24.01.2019 Haus der Kirche, Kassel #3 Gordon Friedrichs, M.A. -

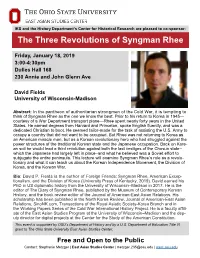

The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee

IKS and the History Department’s Center for Historical Research are pleased to co-sponsor: The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee Friday, January 18, 2019 3:00-4:30pm Dulles Hall 168 230 Annie and John Glenn Ave David Fields University of Wisconsin-Madison Abstract: In the pantheon of authoritarian strongmen of the Cold War, it is tempting to think of Syngman Rhee as the one we know the best. Prior to his return to Korea in 1945— courtesy of a War Department transport plane—Rhee spent nearly forty years in the United States. He earned degrees from Harvard and Princeton, spoke English fluently, and was a dedicated Christian to boot. He seemed tailor-made for the task of assisting the U.S. Army to occupy a country that did not want to be occupied. But Rhee was not returning to Korea as an American miracle man, but as a Korean revolutionary hero who had struggled against the power structures of the traditional Korean state and the Japanese occupation. Back on Kore- an soil he would lead a third revolution against both the last vestiges of the Chosun state– which the Japanese had largely left in place–and what he believed was a Soviet effort to subjugate the entire peninsula. This lecture will examine Syngman Rhee’s role as a revolu- tionary and what it can teach us about the Korean Independence Movement, the Division of Korea, and the Korean War. Bio: David P. Fields is the author of Foreign Friends: Syngman Rhee, American Excep- tionalism, and the Division of Korea (University Press of Kentucky, 2019). -

Vol.9 No.4 WINTER 2016 겨울

겨울 Vol.9 No.4 WINTER 2016 겨울 WINTER 2016 Vol.9 No.4 겨울 WINTER 2016 Vol.9 ISSN 2005-0151 OnOn the the Cover Cover Lovers under the Moon is one of the 30 works found in Hyewon jeonsincheop, an album of paintings by the masterful Sin Yun-bok. It uses delicate brushwork and beautiful colors to portray a romantic mo- ment shared between a man and a wom- an. The poetic line in the center reads, “At the samgyeong hour when the light of the moon grows dim, they only know how they feel,” aptly conveying the heart-felt emo- tions of the lovers. winter Contents 03 04 04 Korean Heritage in Focus Exploration of Korean Heritage 30 Evening Heritage Promenade A Night at a Buddhist Mountain Temple Choi Sunu, Pioneer in Korean Aesthetics Jeongwol Daeboreum, the First Full Moon of the Year Tteok, a Defining Food for Seasonal Festivals 04 10 14 20 24 30 36 42 14 Korean Heritage for the World Cultural Heritage Administration Headlines 48 Sin Yun-bok and His Genre Paintings CHA News Soulful Painting on Ox Horn CHA Events Special Exhibition on the Women Divers of Jeju Korean Heritage in Focus 05 06 Cultural Heritage in the Evening Evening Heritage Promenade The 2016 Evening Heritage Promenade program opened local heritage sites to the public in the evening under seven selected themes: Nighttime Text & Photos by the Promotion Policy Division, Cultural Heritage Administration Views of Cultural Heritage, Night Stroll, History at Night, Paintings at Night, Performance at Night, Evening Snacks, and One Night at a Heritage Site. -

Detailed Species Accounts from The

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book Editors N. J. COLLAR (Editor-in-chief), A. V. ANDREEV, S. CHAN, M. J. CROSBY, S. SUBRAMANYA and J. A. TOBIAS Maps by RUDYANTO and M. J. CROSBY Principal compilers and data contributors ■ BANGLADESH P. Thompson ■ BHUTAN R. Pradhan; C. Inskipp, T. Inskipp ■ CAMBODIA Sun Hean; C. M. Poole ■ CHINA ■ MAINLAND CHINA Zheng Guangmei; Ding Changqing, Gao Wei, Gao Yuren, Li Fulai, Liu Naifa, Ma Zhijun, the late Tan Yaokuang, Wang Qishan, Xu Weishu, Yang Lan, Yu Zhiwei, Zhang Zhengwang. ■ HONG KONG Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (BirdLife Affiliate); H. F. Cheung; F. N. Y. Lock, C. K. W. Ma, Y. T. Yu. ■ TAIWAN Wild Bird Federation of Taiwan (BirdLife Partner); L. Liu Severinghaus; Chang Chin-lung, Chiang Ming-liang, Fang Woei-horng, Ho Yi-hsian, Hwang Kwang-yin, Lin Wei-yuan, Lin Wen-horn, Lo Hung-ren, Sha Chian-chung, Yau Cheng-teh. ■ INDIA Bombay Natural History Society (BirdLife Partner Designate) and Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History; L. Vijayan and V. S. Vijayan; S. Balachandran, R. Bhargava, P. C. Bhattacharjee, S. Bhupathy, A. Chaudhury, P. Gole, S. A. Hussain, R. Kaul, U. Lachungpa, R. Naroji, S. Pandey, A. Pittie, V. Prakash, A. Rahmani, P. Saikia, R. Sankaran, P. Singh, R. Sugathan, Zafar-ul Islam ■ INDONESIA BirdLife International Indonesia Country Programme; Ria Saryanthi; D. Agista, S. van Balen, Y. Cahyadin, R. F. A. Grimmett, F. R. Lambert, M. Poulsen, Rudyanto, I. Setiawan, C. Trainor ■ JAPAN Wild Bird Society of Japan (BirdLife Partner); Y. Fujimaki; Y. Kanai, H. -

Surviving Through the Post-Cold War Era: the Evolution of Foreign Policy in North Korea

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal Title Surviving Through The Post-Cold War Era: The Evolution of Foreign Policy In North Korea Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nj1x91n Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 21(2) ISSN 1099-5331 Author Yee, Samuel Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/B3212007665 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction “When the establishment of ‘diplomatic relations’ with south Korea by the Soviet Union is viewed from another angle, no matter what their subjective intentions may be, it, in the final analysis, cannot be construed otherwise than openly joining the United States in its basic strategy aimed at freezing the division of Korea into ‘two Koreas,’ isolating us internationally and guiding us to ‘opening’ and thus overthrowing the socialist system in our country [….] However, our people will march forward, full of confidence in victory, without vacillation in any wind, under the unfurled banner of the Juche1 idea and defend their socialist position as an impregnable fortress.” 2 The Rodong Sinmun article quoted above was published in October 5, 1990, and was written as a response to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union, a critical ally for the North Korean regime, and South Korea, its archrival. The North Korean government’s main reactions to the changes taking place in the international environment during this time are illustrated clearly in this passage: fear of increased isolation, apprehension of external threats, and resistance to reform. The transformation of the international situation between the years of 1989 and 1992 presented a daunting challenge for the already struggling North Korean government. -

Historical Diary 3 - February 1952

1ST MARINE AIR WING - HISTORICAL DIARY 3 - FEBRUARY 1952 Korean War Korean War Project Record: USMC-201 CD: 03 United States Marine Corps History Division Quantico, Virginia Records: United States Marine Corps Unit Name: 1st Marine Division Records Group: RG 127 Depository: National Archives and Records Administration Location: College Park, Maryland Editor: Hal Barker Korean War Project P.O. Box 180190 Dallas, TX 75218-0190 http://www.koreanwar.org DECLASSIFIED Korean War Project USMC-00318125 \l\i J 1\1 V \1 II \I r:'.._} """'· - . .-' '- r~ J\ 1 I '" L-,'-'<IL• DATr2 ufEB JSS2 SECRET / DECLASSTFTED DECLASSIFIED Korean War Project USMC-00318126 E;!0CijOSUH}-:: (l) to lBl J·.-U.\1 - w ... JJIO>. Gontitu~ 0 1c:'.. ~- -- ... ...... ··-- -- ·--· -· ... - ~-- --- ...... ~ ... ~-- -- ~--· ~~ -- -- - - - ·- - . -- - -- - -· -- -- ~·or u1l1tnl'Y purpOfh;f.l, th1G 1r: n nost 1''\VO!'".b1o hr~ola fron \·Jhich to cxpnnd, r>.nd ono ui tll \'ihioh tho ;_rnitcU. Stntv~ cord(l not cor.1pctc.~~~ The G1r;nlf1onnt VOYCI[;O of tho "Cotlotll cm:nh·•oi~.CG t.Lnt r,lliocl control o:f the ocoetno rtnd the Pl\nt..ttlfl nnd Guo?, Cr.n'llB cnnnot <'l"cvont the Sov1.ctfl fr•or!l trn nnfcr;r1 nc: their nnvnl f'Ol"'C'lcs fi•or:~ :r:urorcnn HtlDRi:t to Fnr En~ torn Ruor.iC~ nn t;Jwy ooc fit for pcr1oc3.o cw long nE; six ~--~Jnthn of tho 'J'Onr·. ~k....Qn.£!n t_l.~l'!l. A.c; of toUuy, th..: cr11,n b1l1 t1 ..:n of tLG '1 SSR to co n<luc t n111 ttLry Ol!DY'ntionn in trw vJ.r 1 n nrctlc nnd ~>ubnrt.t.ic onv.:\ronontEi nrc bul icV'"' to be qunnt1 tn tivoly nur-uriol" to tho .so of tho ·1 n11;el1 3tn. -

Christmas in North Korea

Christmas in North Korea Christmas in North Korea By Adnan I. Qureshi With contributions from Talha Jilani Asad Alamgir Guven Uzun Suleman Khan Christmas in North Korea By Adnan I. Qureshi This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Adnan I. Qureshi All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5054-0 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5054-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contributors .............................................................................................. x Preface ...................................................................................................... xi 1. The Journey to North Korea ............................................................... 1 1.1. Introduction to the Korean Peninsula 1.2. Tour to North Korea 1.3. Introduction to The Pyongyang Times 1.4. Arrival at Pyongyang International Airport 2. Brief History ........................................................................................ 32 2.1. The ‘Three Kingdom’ and ‘Later Three Kingdom’ periods 2.2. Goryeo kingdom 2.3. Joseon kingdom 2.4. Japanese occupation 2.5. Complete Japanese control 2.6. Post-Japanese occupation 2.7. The Korean War 3. Contemporary North Korea .............................................................. 58 3.1. The first communist dynasty and its challenges 3.2. The changing face of the communist economic structure 3.3. Nuclear power 3.4. Rocket technology 3.5. Life amidst sanctions 3.6. Mineral resources 3.7. Mutual defense treaties 3.8. Governmental structure of North Korea 3.9. -

A Theological Analysis of the Non-Church Movement in Korea with a Special Reference to the Formation of Its Spirituality

A THEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE NON-CHURCH MOVEMENT IN KOREA WITH A SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE FORMATION OF ITS SPIRITUALITY by SUN CHAE HWANG A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For the Degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham June 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This study provides a new theological approach for interpreting the Non- Church Movement (NCM) in Korea. Previous studies have been written from a historical perspective. Therefore, an examination of the spirituality and characteristics of the NCM from a theological standpoint is a new approach. The present study investigates the connection between the NCM and Confucianism. It attempts to highlight the influence of Confucian spirituality on the NCM, in particular the Confucian tradition of learning. It also examines the link between the NCM and Quakerism, in particular the influence of Quaker ecclesiology on the NCM. This too has not been examined in previous studies. The thesis argues that the theological roots of NCM ecclesiology lie in the relatively flat ecclesiology of the Quaker movement in the USA. -

Christian Communication and Its Impact on Korean Society : Past, Present and Future Soon Nim Lee University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Christian communication and its impact on Korean society : past, present and future Soon Nim Lee University of Wollongong Lee, Soon Nim, Christian communication and its impact on Korean society : past, present and future, Doctor of Philosphy thesis, School of Journalism and Creative Writing - Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3051 This paper is posted at Research Online. Christian Communication and Its Impact on Korean Society: Past, Present and Future Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Wollongong Soon Nim Lee Faculty of Creative Arts School of Journalism & Creative writing October 2009 i CERTIFICATION I, Soon Nim, Lee, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Creative Arts and Writings (School of Journalism), University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Soon Nim, Lee 18 March 2009. i Table of Contents Certification i Table of Contents ii List of Tables vii Abstract viii Acknowledgements x Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Christianity awakens the sleeping Hangeul 12 Introduction 12 2.1 What is the Hangeul? 12 2.2 Praise of Hangeul by Christian missionaries -

Korea's Dynamic Role in East Asia: Interaction, Innovation

KOREA’S DYNAMIC ROLE IN EAST ASIA: INTERACTION, INNOVATION, AND DIFFUSION GRADES: 9 - 12 AUTHORS: Jamie Paoloni, Whitney Sholler, Zoraida Velez SUBJECT: AP World History, World History TIME REQUIRED: Four to five class periods OBJECTIVES: 1. Locate important political boundaries, landforms, bodies of water, and trade routes on the maps of East Asia and Korea. 2. Identify the significance of the Koguryo, Paekche, Silla, Koryo, and Chosŏn Periods in Korean history 3. Analyze the significance of the Silk Road on Korean history and culture 4. Analyze the influence of China on Korean history and culture 5. Identify Korean innovations in religion, art, and architecture 6. Analyze the influence of Korea on Japanese history and culture STANDARDS: NCSS Standards: Standard1: Culture a. Human beings create, learn, share, and adapt to culture b. Cultures are dynamic and change over time Standard 3: People, Places and Environments Standard 9: Global Connections Common Core Standards: RH 1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, attending to such features as the date and origin of the information RH 2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source RH 7 Integrate an. Evaluate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media WHST 1 Write arguments focused on discipline-specific content WHST 4 Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience. WHST 7 Conduct short as well as more