Cultural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

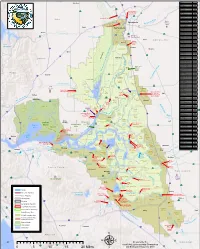

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

Historic Context Statement City of Benicia February 2011 Benicia, CA

Historic Context Statement City of Benicia February 2011 Benicia, CA Prepared for City of Benicia Department of Public Works & Community Development Prepared by page & turnbull, inc. 1000 Sansome Street, Ste. 200, San Francisco CA 94111 415.362.5154 / www.page-turnbull.com Benicia Historic Context Statement FOREWORD “Benicia is a very pretty place; the situation is well chosen, the land gradually sloping back from the water, with ample space for the spread of the town. The anchorage is excellent, vessels of the largest size being able to tie so near shore as to land goods without lightering. The back country, including the Napa and Sonoma Valleys, is one of the finest agriculture districts in California. Notwithstanding these advantages, Benicia must always remain inferior in commercial advantages, both to San Francisco and Sacramento City.”1 So wrote Bayard Taylor in 1850, less than three years after Benicia’s founding, and another three years before the city would—at least briefly—serve as the capital of California. In the century that followed, Taylor’s assessment was echoed by many authors—that although Benicia had all the ingredients for a great metropolis, it was destined to remain in the shadow of others. Yet these assessments only tell a half truth. While Benicia never became the great commercial center envisioned by its founders, its role in Northern California history is nevertheless one that far outstrips the scale of its geography or the number of its citizens. Benicia gave rise to the first large industrial works in California, hosted the largest train ferries ever constructed, and housed the West Coast’s primary ordnance facility for over 100 years. -

Tidal Marsh Recovery Plan Habitat Creation Or Enhancement Project Within 5 Miles of OAK

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Recovery Plan for Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California California clapper rail Suaeda californica Cirsium hydrophilum Chloropyron molle Salt marsh harvest mouse (Rallus longirostris (California sea-blite) var. hydrophilum ssp. molle (Reithrodontomys obsoletus) (Suisun thistle) (soft bird’s-beak) raviventris) Volume II Appendices Tidal marsh at China Camp State Park. VII. APPENDICES Appendix A Species referred to in this recovery plan……………....…………………….3 Appendix B Recovery Priority Ranking System for Endangered and Threatened Species..........................................................................................................11 Appendix C Species of Concern or Regional Conservation Significance in Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California….......................................13 Appendix D Agencies, organizations, and websites involved with tidal marsh Recovery.................................................................................................... 189 Appendix E Environmental contaminants in San Francisco Bay...................................193 Appendix F Population Persistence Modeling for Recovery Plan for Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California with Intial Application to California clapper rail …............................................................................209 Appendix G Glossary……………......................................................................………229 Appendix H Summary of Major Public Comments and Service -

Food Webs of the Delta, Suisun Bay, and Suisun Marsh: an Update on Current Understanding and Possibilities for Management Larry R

OCTOBER 2016 SPECIAL ISSUE: STATE OF BAY–DELTA SCIENCE 2016, PART 2 Food Webs of the Delta, Suisun Bay, and Suisun Marsh: An Update on Current Understanding and Possibilities for Management Larry R. Brown1*, Wim Kimmerer2, J. Louise Conrad3, Sarah Lesmeister3, and Anke Mueller–Solger1 to species of concern; however, data from other Volume 14, Issue 3 | Article 4 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2016v14iss3art4 regions of the estuary suggest that this conceptual model may not apply across the entire region. * Corresponding author: [email protected] Habitat restoration has been proposed as a method 1 California Water Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey of re-establishing historic food web processes to Sacramento, CA 95819 USA support species of concern. Benefits are likely for 2 Romberg Tiburon Center, San Francisco State University Tiburon, CA 94920 USA species that directly access such restored habitats, 3 California Department of Water Resources but are less clear for pelagic species. Several topics Sacramento, CA 95691 USA require attention to further improve the knowledge of food webs needed to support effective management, including: (1) synthesis of factors responsible for ABSTRACT low pelagic biomass; (2) monitoring and research on effects of harmful algal blooms; (3) broadening This paper reviews and highlights recent research the scope of long-term monitoring; (4) determining findings on food web processes since an earlier benefits of tidal wetland restoration to species of review by Kimmerer et al. (2008). We conduct this concern, including evaluations of interactions of review within a conceptual framework of the Delta– habitat-specific food webs; and (5) interdisciplinary Suisun food web, which includes both temporal and analysis and synthesis. -

Suisun Marsh Fish Report 2018 Final.Pdf

Trends in Fish and Invertebrate Populations of Suisun Marsh January 2018 - December 2018 Annual Report for the California Department of Water Resources Sacramento, California Teejay A. O'Rear*, Peter B. Moyle, and John R. Durand Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology Center for Watershed Sciences University of California, Davis October 2020 *Corresponding author: [email protected] SUMMARY Suisun Marsh, at the geographic center of the northern San Francisco Estuary, is important habitat for native and non-native fishes. The University of California, Davis, Suisun Marsh Fish Study, in partnership with the California Department of Water Resources (DWR), has systematically monitored the marsh's fish populations since January 1980. The study’s main purpose has been to determine environmental and anthropogenic factors affecting fish distribution and abundance. Abiotic conditions in Suisun Marsh during calendar-year 2018 returned to fairly typical levels following the very wet year of 2017. Delta outflow was generally low, with higher-than- average outflows only occurring in April when Yolo Bypass flooded. Salinities in 2018 were about average, in part because of Suisun Marsh Salinity Control Gates operations in late summer. Water temperatures were mild, being higher than average in winter and autumn and slightly below average during summer. Water transparencies were typical in winter and spring but, as has become a pattern since the early 2000s, were higher than average in summer and autumn. Dissolved-oxygen concentrations were consistent throughout the year, with only two instances of low values being recorded, both in dead-end sloughs. Fish and invertebrate catches in Suisun Marsh in 2018 told two main stories: (1) many fishes benefit from higher flows and lower salinities in Suisun Marsh while some invasive invertebrates do not; and (2) Suisun Marsh is disproportionately valuable to fishes of conservation importance. -

NMFS and USFWS Biological Assessment

LOS GATOS CREEK BRIDGE REPLACEMENT / SOUTH TERMINAL PHASE III PROJECT NMFS and USFWS Biological Assessment Prepared for Peninsula Corridor Joint Powers Board 1250 San Carlos Avenue P.O. Box 3006 San Carlos, California 94070-1306 and the Federal Transit Administration Region IX U.S. Department of Transportation 201 Mission Street Suite1650 San Francisco, CA 94105-1839 Prepared by HDR Engineering, Inc. 2379 Gateway Oaks Drive Suite 200 Sacramento, California 95833 August 2013 NMFS and USFWS Biological Assessment Prepared for Peninsula Corridor Joint Powers Board 1250 San Carlos Avenue P.O. Box 3006 San Carlos, California 94070-1306 and the Federal Transit Administration Region IX U.S. Department of Transportation 201 Mission Street Suite 1650 San Francisco, CA 94105-1839 Prepared by HDR Engineering, Inc. 2379 Gateway Oaks Drive, Suite 200 Sacramento, California 95833 August 2013 This page left blank intentionally. Summary The Peninsula Corridor Joint Powers Board (JPB) which operates the San Francisco Bay Area’s Caltrain passenger rail service proposes to replace the two-track railroad bridge that crosses Los Gatos Creek, in the City of San Jose, Santa Clara County, California. The Proposed Action is needed to address the structural deficiencies and safety issues of the Caltrain Los Gatos Creek railroad bridge to be consistent with the standards of safety and reliability required for public transit, to ensure that the bridge will continue to safely carry commuter rail service well into the future, and to improve operations at nearby San Jose Diridon Station and along the Caltrain rail line. This Biological Assessment (BA) has been prepared for the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and U.S. -

Trends in Fish and Invertebrate Populations of Suisun Marsh January 2017

Trends in Fish and Invertebrate Populations of Suisun Marsh January 2017 - December 2017 Annual Report for the California Department of Water Resources Sacramento, California Teejay A. O'Rear, Peter B. Moyle, and John R. Durand Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology Center for Watershed Sciences University of California, Davis January 2019 SUMMARY Suisun Marsh, at the geographic center of the northern San Francisco Estuary, is important habitat for native and non-native fishes. The University of California, Davis, Suisun Marsh Fish Study, in partnership with the California Department of Water Resources (DWR), has systematically monitored the marsh's fish populations since January 1980. The study’s main purpose has been to determine environmental and anthropogenic factors affecting fish distribution and abundance. Calendar year 2017 was wet and warm. Very high Delta outflows resulted in nearly freshwater conditions throughout Suisun Marsh from January to July, with lower-than-average salinities persisting until November. Matching the local climate, water temperatures were generally warmer than usual. Unlike most of the last 10 years when water transparencies greatly increased relative to the average in summer and autumn, water transparencies stayed near or below average for the latter half of 2017. Dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations were sufficient for marsh fishes except in March in upper Goodyear Slough, when DO concentrations dipped below 3 milligrams per liter (mg/L). The aquatic community of Suisun Marsh responded to the wet, warm conditions. Non- native overbite clams (Potamocorbula amurensis), which require a salinity of at least 2 parts per thousand (ppt) for successful reproduction, were never abundant in 2017. -

38Th Annual Salmonid Restoration Conference

Salmonid Restoration Federation’s Mission Statement 38th Annual Salmonid Restoration Conference Salmonid Restoration Federation was formed in 1986 to help stream March 31 – April 3, 2020 Santa Cruz, CA restoration practitioners advance the art and science of restoration. Salmonid Restoration Federation promotes restoration, stewardship, 2020 Vision for California’s Salmonscape and recovery of California native salmon, steelhead, and trout populations through education, collaboration, and advocacy. 38 th Annual Salmonid Restoration Conference • 2020, Santa Cruz, CA Conference • 2020, Restoration Salmonid Annual SRF Goals & Objectives 1. To provide affordable technical education and best management practices trainings to the watershed restoration community. Conference Co-Sponsors Balance Hydrologics, Inc., Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria, 2. Conduct outreach to constituents, landowners, and decision-makers Cachuma Operation and Maintenance Board, California American Water, California Conservation Corps, to inform the public about the plight of endangered salmon and California Department of Fish and Wildlife, California Department of Water Resources, the need to preserve and restore habitat to recover salmonid California State Coastal Conservancy, CalTrans, California Trout - North Coast, Cardno, cbec, inc., City of Santa Cruz-Water Branch, County of Santa Cruz, East Bay Municipal Utility District, populations. Environmental Science Associates, Eureka Water Probes, FISHBIO, GHD, Green Diamond Resource Company - CA Timberlands -

2. the Legacies of Delta History

2. TheLegaciesofDeltaHistory “You could not step twice into the same river; for other waters are ever flowing on to you.” Heraclitus (540 BC–480 BC) The modern history of the Delta reveals profound geologic and social changes that began with European settlement in the mid-19th century. After 1800, the Delta evolved from a fishing, hunting, and foraging site for Native Americans (primarily Miwok and Wintun tribes), to a transportation network for explorers and settlers, to a major agrarian resource for California, and finally to the hub of the water supply system for San Joaquin Valley agriculture and Southern California cities. Central to these transformations was the conversion of vast areas of tidal wetlands into islands of farmland surrounded by levees. Much like the history of the Florida Everglades (Grunwald, 2006), each transformation was made without the benefit of knowing future needs and uses; collectively these changes have brought the Delta to its current state. Pre-European Delta: Fluctuating Salinity and Lands As originally found by European explorers, nearly 60 percent of the Delta was submerged by daily tides, and spring tides could submerge it entirely.1 Large areas were also subject to seasonal river flooding. Although most of the Delta was a tidal wetland, the water within the interior remained primarily fresh. However, early explorers reported evidence of saltwater intrusion during the summer months in some years (Jackson and Paterson, 1977). Dominant vegetation included tules—marsh plants that live in fresh and brackish water. On higher ground, including the numerous natural levees formed by silt deposits, plant life consisted of coarse grasses; willows; blackberry and wild rose thickets; and galleries of oak, sycamore, alder, walnut, and cottonwood. -

Suisun Marsh Plan-Chap 5

Chapter 5 Physical Environment This chapter provides environmental analyses relative to physical parameters of the project area. Components of this study include a setting discussion, impact analysis criteria, project effects and significance, and applicable mitigation measures. This chapter is organized as follows: Section 5.1, “Water Supply, Hydrology, and Delta Water Management”; Section 5.2, “Water Quality”; Section 5.3, “Geology and Groundwater”; Section 5.4, “Flood Control and Levee Stability”; Section 5.5, “Sediment Transport”; Section 5.6, “Transportation and Navigation”; Section 5.7, “Air Quality”; Section 5.8, “Noise”; and Section 5.9; “Climate Change.” Suisun Marsh Habitat Management, November 2011 Preservation, and Restoration Plan 5-1 Final EIS/EIR ICF 06888.06 Section 5.1 Water Supply, Hydrology, and Delta Water Management Introduction This section describes the existing environmental conditions and the consequences of implementing the SMP alternatives on water supply, hydrology, and Delta water management. Delta water management for agriculture, water supply diversions, and exports and the salinity of water diverted for waterfowl habitat in the managed wetlands of the Marsh officially became linked in the 1978 State Water Board Delta Water Control Plan and the water right decision (D-1485) Suisun Marsh salinity standards (objectives). D-1485 required DWR and Reclamation to prepare a plan to protect the beneficial use of water for fish and wildlife and meet salinity standards for the Marsh. Initial facilities included improved RRDS facilities to supply approximately 5,000 acres on Simmons, Hammond, Van Sickle, Wheeler, and Grizzly Islands with lower salinity water from Montezuma Slough, and the MIDS and Goodyear Slough outfall to improve supply of lower salinity water for the southwestern Marsh. -

Conceptual Model for Managed Wetlands in Suisun Marsh

Initial Draft Conceptual Model for Managed Wetlands in Suisun Marsh Compiled by Department of Fish and Game (DFG) and Suisun Resource Conservation District (SRCD) staff Contributors: Laureen Barthman – Thompson (DFG) Kristin Bruce (SRCD) Sarah Estrella (DFG) Paul Garrison III (DFG) Craig Haffner (SRCD) Julie Niceswanger (DFG) Gina Van Klompenburg (DFG) Bruce Wickland (SRCD) With input from: Dennis Becker Laurie Briden Cecilia Brown Steve Chappell Steve Culberson Cassandra Enos Chris Enright Bellory Fong Terri Gaines Jasper Lament Conrad Jones Victor Pacheco Facilitated by: Zachary Hymanson Stuart Siegel 1 Table of Contents 1.0 MANAGED WETLAND MANAGEMENT GOALS AND ASSUMPTIONS .................................. 5 2.0 CURRENT CONDITIONS .................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 PHYSICAL .......................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1.1 Applied water salinity .................................................................................................................. 6 2.1.2 Slough water salinity / Marsh-wide salinity gradient (DWR 2001) ............................................. 7 2.1.3 Soils .............................................................................................................................................. 7 2.1.4 Water year ................................................................................................................................... -

DELTA SMELT Action Plan

DELTA SMELT Action Plan October 2005 State of California The Resources Agency Department of Water Resources Department of Fish and Game Contents Executive Summary ................................................................. i Background The Bay-Delta ................................................................1 The Interagency Ecological Program ................................6 The CALFED Bay-Delta Program ......................................8 Overview Pelagic Organism Decline ............................................14 Conceptual Model of Decline ........................................16 IEP Study Plan .............................................................21 Action Plan Potential Actions ..........................................................23 CALFED Bay-Delta Program Actions ................................24 Ecosystem Restoration Program Actions ....................26 Delta Actions ........................................................26 Suisun Marsh Actions.............................................31 Increase Food Web Productivity ..............................35 Reduce Entrainment at Power Plants .........................40 Environmental Water Account Actions ......................43 Modified Environmental Water Account ...................44 EWA Decision-Making for Export Curtailments ..........46 Conveyance Actions ..............................................49 Conveyance Modifications .....................................49 Modified Barrier Installation at the Head of Old River ........................................51