The Songs of Nicolae Bretan Golem & Arald , Operas in One Act (NI 5424)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soprano | Complete Repertoire | Opera | Oratorio | Songs

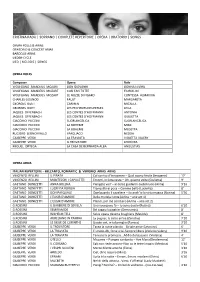

CRISTINA RADU | SOPRANO | COMPLETE REPERTOIRE | OPERA | ORATORIO | SONGS OPERA ROLES & ARIAS ORATORIO & CONCERT ARIAS BAROQUE ARIAS LIEDER-CYCLE LIED | MELODIE | SONGS OPERA ROLES Composer Opera Role WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART DON GIOVANNI DONNA ELVIRA WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART COSI FAN TUTTE FIORDILIGI WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART LE NOZZE DI FIGARO CONTESSA ALMAVIVA CHARLES GOUNOD FAUST MARGARETA GEORGES BIZET CARMEN MICAELA GEORGES BIZET LES PECHEURS DES PERLES LEILA JAQUES OFFENBACH LES CONTES D’HOFFMANN ANTONIA JAQUES OFFENBACH LES CONTES D’HOFFMANN GIULIETTA GIACOMO PUCCINI SUOR ANGELICA SUOR ANGELICA GIACOMO PUCCINI LA BOHEME MIMI GIACOMO PUCCINI LA BOHEME MUSETTA RUGIERO LEONCAVALLO I PAGLIACCI NEDDA GIUSEPPE VERDI LA TRAVIATA VIOLETTA VALERY GIUSEPPE VERDI IL TROVATORE LEONORA MIGUEL ORTEGA LA CASA DE BERNARDA ALBA ANGUSTIAS OPERA ARIAS ITALIAN REPERTOIRE – BELCANTO, ROMANTIC & VERISMO ARIAS ARIAS VINCENZO BELLINI IL PIRATA Col sorriso d’innocenza – Qual suono ferale (Imogene) 12’ VINCENZO BELLINI MONTECCHI I CAPULETTI Eccomi, in lieta vesta – Oh, quante volte (Giulietta) 9’ GAETANO DONIZETTI ANNA BOLENA Piangete voi? – al dolce guidarmi castel natio (Anna) 9’16 GAETANO DONIZETTI LUCREZIA BORGIA Tranquillo ei posa – Comme bello (Lucrezia) 8’ GAETANO DONIZETTI DON PASQUALE Quel guardo il cavaliere – So anch’io la virtu magica (Norina) 5’56 GAETANO DONIZETTI L’ELISIR D’AMORE Della crudela Isotta (Adina – arie act 1) GAETANO DONIZETTI L’ELISIR D’AMORE Prendi, per me sei libero (Adina – arie act 2) G.ROSSINI IL BARBIERE DI SEVILLA Una voce -

A Trubadúr Rigoletto Otello Tannhäuser Iphigénie Auf Tauris Az Árnyék

OPERA REPERTOÁR OPERA REPERTOÁR OPERA REPERTOÁR BALETT REPERTOÁR BALETT REPERTOÁR BALETT REPERTOÁR G. Verdi G. Verdi Ch. W. Gluck – R. Strauss R. North – B. Downes / A. Bournonville – H. S. Løvenskiold: Harangozó Gyula – L. Delibes J. Cranko – P. I. Csajkovszkij A TRUBADÚR OTELLO IPHIGÉNIE AUF TaURIS TRÓJAI JÁTÉKOK / A SZILFID COPPÉLIA ANYEGIN Opera két részben Opera három részben Opera két részben Táncjáték három felvonásban Balett három felvonásban TRÓJAI JÁTÉKOK Karmester u Kovács János Karmester u Marco Comin Karmester u Vashegyi György Férfi balettparódia egy felvonásban Karmester u Kovács László Karmester u Silló István | Szennai Károly Rendező u Vámos László Rendező u Vámos László Rendező u Alföldi Róbert Koreográfus u Harangozó Gyula Koreográfus u John Cranko Koreográfus u Robert North Színpadra állította u ifj. Harangozó Gyula A főbb szerepekben u Fokanov Anatolij | Létay Kiss Gabriella | Sümegi Eszter A főbb szerepekben u José Cura | Marco Berti | Pasztircsák Polina A főbb szerepekben u Wierdl Eszter | Gál Gabi | Megyesi Zoltán | Haja Zsolt Cranko klasszikus balettje nagyszerűen bizonyítja, hogy Puskin költeménye a Walter Fraccaro | Hector Lopez Mendoza | Ulbrich Andrea | Wiedemann Bernadett Fokanov Anatolij | Dobi – Kiss Veronika | Nyári Zoltán Johannes von Duisburg | Zavaros Eszter Robert North angol koreográfus azért készítette balettjét, hogy sajátosan ironikus látás- Tanulságos párkapcsolati tréning, melynek közepén egy harangavatás áll. Címszereplő világirodalomnak olyan gyöngyszeme, amely örök érvényű emberi viszonyokat -

Application/Pdf 983.64 KB

BIOGRAFÍAS ANGELA TEODOR CIPRIAN GHEORGHIU ILINCĂI TEODORAŞCU TEMPORADA 2017-2018 Es una de las sopranos más Tras estudiar oboe y filología, Nació en Galati, Rumanía, y es destacadas de las últimas este tenor rumano se graduó en director en la Ópera Nacional décadas. Nació en Adjud, la Universidad de Música de de Rumanía en Bucarest desde Rumanía, y se graduó en la Bucarest. Inició su carrera 2003. Graduado de la Universidad Nacional de profesional en la Ópera Universidad Nacional de Música de Bucarest. Debutó Nacional de Rumanía en 2008. Música, estudió en Francia en la Royal Opera House de Fue premiado en importantes con el director Alain Paris, Londres en 1992 como Mimì concursos de canto, como el de especialista en repertorio (La bohème) y ese mismo año en Szczecin (2008) y el Viñas francés. Ha trabajado con casi la Metropolitan Opera House (2010). Su debut internacional, todas las instituciones de Nueva York y la Staatsoper en 2009, tuvo lugar en la Ópera musicales de su país, como las de Viena. En 1994 interpretó de Hamburgo con Macduff óperas de Brasov y Timisoara, por primera vez a Violetta (Macbeth), y ese mismo año el Teatro Nacional de Opereta (La traviata) con gran éxito debutó en la Staatsoper de de Bucarest, así como con la de público y crítica. Desde Viena como Ismaele (Nabucco). Radio Televisión Rumana. Ha entonces ha cantado en los más Ha cantado en algunos de los dirigido en la Ópera de Sarajevo reputados escenarios de París teatros más prestigiosos del y en el Teatro Malibran de Breguet La Classique a Buenos Aires, pasando por mundo, como la Royal Opera Venecia, y ha colaborado con Classique Extra-Plate Guillochée 7147 Ámsterdam, Kuala Lumpur, House de Londres, la Opéra destacados artistas rumanos (el Los Ángeles, Milán, Moscú national de Paris, el Liceu de bajo Eduard Tumagian, los y Zúrich. -

Bollettino Novità Biblioteca Armando Gentilucci Dell'istituto Superiore Di Studi Musicali Di Reggio Emilia E Castelnovo Ne' Monti

Bollettino novità Biblioteca Armando Gentilucci dell'Istituto Superiore di Studi Musicali di Reggio Emilia e Castelnovo ne' Monti Stampato il 22/09/14 Parametri di ricerca comunicati: (Biblioteca: BIBLIOTECA ARMANDO GENTILUCCI DELL'ISTITUTO SUPERIORE DI STUDI MUSICALI ) AND (Categoria: Libro Moderno OR Categoria: Libro Antico OR Categoria: Audiovisivo OR Categoria: Musica OR Categoria: Materiale sonoro OR Categoria: Collana ) AND (Periodo di acquisizione: Ultimo semestre ) AND (InvSerieBiblio: ISS ) AND (Anno pubblicazione: 1990 OR Anno pubblicazione: 2014 ) AND (Tipologia: Registrazione sonora musicale OR Tipologia: Materiale video OR Tipologia: Video musicale ) Bollettino novità Biblioteca Armando Gentilucci dell'Istituto Superiore di Studi Musicali di Reggio Emilia e Castelnovo ne' Monti 1 [Materiale video] *Alice Mafessoni, flauto; Silvia Storchi, clarinetto; Silvia Ciammaglichella, pianoforte / musiche di J. Francaix, I. Stravinsky, J. S. Bach, F. Martin, J. Ibert. - San Martino in Rio : Villa Nostradamus, 2014. - 1 DVD ; 12 cm. ((Titolo del contenitore. - DVD realizzato in occasione dell'iniziativa "L'ora della musica" promossa dall'Istituto Superiore di Studi Musicali di Reggio Emilia e Castelnovo ne' Monti, sede "A. Peri", domenica 23 marzo 2014. Biblioteca Inventario Collocazione BIBLIOTECA ARMANDO ISS 9267 MEDIATECA DVD GENTILUCCI DELL'ISTITUTO OM 2014 0009 SUPERIORE DI STUDI MUSICALI 2 [Registrazione sonora musicale] *Prélude : live recording Falaut campus / [musiche di] B. Godart, A. Dvorak, A. Bazzini, C. Debussy, F. Martin, F. Borne, J. Massenet ; Paolo Taballione, flauto ; Amedeo Salvato, pianoforte. - [Pompei] : Falaut, 2014. - 1 compact disc ; 12 cm. ((Allegato a: Falaut, gennaio-marzo 2014, n. 60. - Registrazione live: concerto del 22 agosto 2013, Sala Marte Mediateca [Cava dei Tirreni, Salerno]. (Falaut collection) Biblioteca Inventario Collocazione BIBLIOTECA ARMANDO ISS 9967 MEDIATECA CD D GENTILUCCI DELL'ISTITUTO 1050 SUPERIORE DI STUDI MUSICALI 3 [Registrazione sonora musicale] *Jihoon Shin / [esegue musiche di] P. -

CURRICULUM VITAE NIKITA STOROJEV, Bass

CURRICULUM VITAE NIKITA STOROJEV, Bass http://www.nikitastorojev.com Education 1970-72 State University at Sverdlovsk; Philosophy Major 1972-75 Mussorgsky Conservatory of Yekaterinburg Mastered bel canto technique under the direction of professor Ian Voutiras 1975-78 Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory of Music Diplomas received: Opera Singer ( оперный певец ) Chamber Music Singer ( камерный певец ) Professor of Voice ( педагог оперного пения ) 1977-80 Studied stage directing under professor/stage director Joseph Tumanov Studied and specialized in stage interpretation under Professor Eugene Nesterenko Private lessons with Tonini (coach of Pavarotti), Nicolai Ghiaurov, Jerome Hines and Giulio Fioravanti Professional Qualifications (Opera/Concert Performance) 1976-81 Principal soloist at the Bolshoi Opera 1978 Winner of International Tchaikovsky Competition, Moscow 1976-81 Principal soloist, Philharmonic Society of Moscow, gaining experience from working with the best Russian orchestras and conductors; Eugene Svetlanov, Gennady Rozhdestvenski, Boris Hikin, Yuri Fedosseyev, Valéry Gergiev 1983-85 Principal soloist with the Deutsche Oper am Rhein, Düsseldorf. Italian repertoire prepared and performed with Alberto Erede. German repertoire prepared and performed with Peter Schneider (conductor) and Yuri Kout (conductor). 1983-2007 Principal guest soloist at the opera houses, concert halls and international festivals: Milan, New York, Paris, London, Vienna, Berlin, Madrid, München, Moscow, St. Petersburg, Amsterdam, Rome, Tokyo, San Francisco….. Languages: Russian, English, Spanish, Italian, German, French Academic Employment 2007-2001 Assistant Professor of Voice and Opera, University of Texas at Austin 1997-1996 Professor of Voice and Opera, Schola Cantorum, Paris: 1982-1981 Professor, Escuela Superior de Música, Monterrey 1977-1978: Assistant to Eugene Nesterenko in Moscow Conservatory Teaching Experience 2001-2007 Assistant Professor, Voice/Opera Division, University of Texas at Austin 1978-2007 Master classes in: Moscow Conservatory, St. -

Tenor Richard Leech

Tenor Richard Leech Discography Solo from the heart Telarc International CD-80432 (1 CD) Italian Arias and Neapolitan Songs Works by Cilea, Donizetti, Puccini, Verdi, De Curtis, Di Capua, Leoncavallo, Tosti London Symphony Orchestra John Fiore, cond. Berlioz La Damnation de Faust London/Decca 444 812-2 (2 CDs) with Françoise Pollet, Gilles Cachemaille Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal Charles Dutoit, cond. Hymne des Marseillaises Telarc International 80164 (1 CD) with Silvia McNair Baltimore Symphony Orchestra David Zinman, cond. Donizetti Dom Sébastien Legato Classics LCD 190-2 (2 CDs) with Klara Takacs, Lajos Miller, Sergej Koptchak Opera Orchestra of New York Eve Queler, cond. 2 Gounod Faust EMI Classics CDCC 54228 (3 CDs) CDCC 54358 (1 CD Highlights) with Cheryl Studer, Thomas Hampson, José van Dam Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse Michel Plasson, cond. Mahler Symphony No. 8 in E-flat (Symphony of a Thousand) SONY Classical S2K 45754 (2 CDs) with Sharon Sweet, Pamela Coburn, Florence Quivar, Brigitte Fassbänder, Siegmund Nimsgern, Simon Estes, Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Lorin Maazel, cond. Meyerbeer Les Huguenots Erato 2292-45027-2 (4 CDs) with Françoise Pollet, Ghylaine Raphanel, Danielle Borst, Gilles Cachemaille, Boris Martinovic, Nicola Ghiuselev Orchestre Philharmonique de Montpellier Cyril Diedrich, cond. Puccini La Bohème Erato 0630-10699-2 (2 CDs) with Kiri Te Kanawa, Nancy Gustafson, Alan Titus, Gino Quilico, Roberto Scandiuzzi London Symphony Orchestra Kent Nagano, cond. 3 J. Strauss Die Fledermaus (Alfred) Philips 432 157-2 (2 CDs) 438 503-2 (1 CD - Highlights) with Te Kanawa, Gruberova, Fassbänder, Brendel, Bär, Krause Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra André Previn, cond. R.Strauss Der Rosenkavalier (Italian Tenor) EMI Classics CDCC 54259 (3 CDs) with Kiri Te Kanawa, Barbara Hendricks, Anne Sofie von Otter, Kurt Rydl Staatskapelle Dresden Bernard Haitink, cond. -

Pot Înţelege Motivul Pentru Care Scena Lirică Bucureşteană Şi-A

Pot înţelege motivul pentru care scena lirică bucureşteană şi-a înscris pe afişul celei dintâi premiere a anului 2009 spectacolul-coupe Go/em - Arald: Opera care s-a numit multă vreme "Română", iar acum este "Naţională", avea neapărată nevoie să-şi îmbogăţească urgent repertoriul autohton, cu deosebire precar. Pot înţelege şi de ce, pentru acest demers, a fost ales numele compozitorului Nicolae Bretan (1887-1968), muzician format la Cluj (1906-1 908) şi perfecţionat la Viena (1908-1909) şi Budapesta (1909-1 912), cântăreţ la Bratislava (1913-1914) şi Oradea (1914-1916), revenit în cele din urmă la Cluj, unde a fost, rând pe rând, solist şi regizor la Te atrul Maghiar (1917-1 922), prim-bariton (1922-1940), regizor (1922-1940, 1946-1 948) şi director (1944-1945) la Opera Română, regizor la Te atrul de Stat şi la Opera Maghiară (1940-1 944): chiar dacă valoarea acestui artist (cunoscut ca autor mai cu seamă graţie nenumăratelor sale lieduri) îl pla sează cu mult în urma confratilor mai vechi sau mai noi care s-au încumetat să scrie în pretenţiosul gen al dramei muzicale, alte avantaje - de ordin administrativ şi economic - îl făceau eligibil. Pot înţelege până şi faptul că, din creaţia lirica-dramatică a lui Nicolae Bretan, nu s-a optat pentru Luceafărul sau pentru Eroii de la Ravine (opere într-un act, dar cu mai multe tablouri), şi cu atât mai puţin pentru Horia (în trei acte!), ci pentru aceste două lucrări, nu numai concise, dar şi. .. sumare: decor unic, per sonaje (extrem de) puţine, cor absent (cu totul, în Arald; de pe scenă doar, -

Opera Națională București

Ministerul Culturii şi Patrimoniului NaŃional Raport de activitate pentru perioada Opera NaŃională Bucureşti 15.12.2005 – 01.07.2010 Cătălin A. Ionescu – director general RAPORT DE ACTIVITATE a) EvoluŃia instituŃiei în raport cu mediul în care şi-a desfăşurat activitatea şi în raport cu sistemul instituŃional existent a.1 sinteză a colaborării cu instituŃiile / organizaŃiile etc. culturale care se adresează acelei aşi comunităŃi – tipul / forma de colaborare, cu menŃionarea proiectelor reprezentative desfăşurate împreună cu acestea Locul Creatori Anul Proiectul Autorul Parteneri Data Descriere desfăşurării artistici 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Regia : sponsorizată de CEE Musiktheater şi Alexander American Express, producŃia a fost Opera Rădulescu reprezentată la Bucureşti şi la Le Nozze di NaŃională W.A. Mozart (Germania), 01.dec. Timişoara (perioada ianuarie – aprilie O.N.B. Română Figaro scenografia : 2007), urmând ca din stagiunea 2007 – Timişoara Adrianei 2008 să fie reprezentată doar pe scena Urmuzescu ONB. dirijor : Nayden Todorov 2006 (Opera din Ruse) Die Opera din regizor : Spectacolul a avut loc cu participarea O.N.B. W.A. Mozart Ruse Răzvan Dincă, 17.dec. unor solişti bulgari la Bucureşti şi a Zauberflöte (Bulgaria) scenografia : unor solişti români la Ruse Puiu Iordăchescu mişcarea scenică : Florin Fieroiu dirijor : Tiberiu Soare regizor : Andreea Michel Vălean Spectacol de muzica barocă - Pignolet de Teatrul coregrafie : Spectacolul s-a desfăşurat cu Pyram şi Monteclair şi NaŃional de Mary Collins participarea ansamblului instrumental 2007 T.N.O. 20.apr. Thisbe John Operetă mişcare de muzică barocă Collegio Stravagante Frederick “Ion Dacian” scenică : Maria – a fost solicitat pentru a fi prezentat la Lampe Popa festivaluri de muzică barocă decoruri : Ana Olteanu costume : Ana Alexe regia : Peter Pawlik (Austria), sponsorizată de CEE Musiktheater - Teatrul decoruri : producŃia a avut reprezentaŃii la La Gioacchino NaŃional Vesna Rezic Bucureşti, după care a fost preluată de O.N.B. -

A C AHAH C (Key of a Major, German Designation) a Ballynure Ballad C a Ballynure Ballad C (A) Bal-Lih-N'yôôr BAL-Ludd a Capp

A C AHAH C (key of A major, German designation) A ballynure ballad C A Ballynure Ballad C (A) bal-lih-n’YÔÔR BAL-ludd A cappella C {ah kahp-PELL-luh} ah kahp-PAYL-lah A casa a casa amici C A casa, a casa, amici C ah KAH-zah, ah KAH-zah, ah-MEE-chee C (excerpt from the opera Cavalleria rusticana [kah-vahl-lay-REE-ah roo-stee-KAH-nah] — Rustic Chivalry; music by Pietro Mascagni [peeAY-tro mah-SKAH-n’yee]; libretto by Guido Menasci [gooEE-doh may-NAH-shee] and Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti [jo-VAHN-nee tar-JO- nee-toht-TSAYT-tee] after Giovanni Verga [jo-VAHN-nee VAYR-gah]) A casinha pequeninaC ah kah-ZEE-n’yuh peh-keh-NEE-nuh C (A Tiny House) C (song by Francisco Ernani Braga [frah6-SEESS-kôô ehr-NAH-nee BRAH-guh]) A chantar mer C A chantar m’er C ah shah6-tar mehr C (12th-century composition by Beatriz de Dia [bay-ah-treess duh dee-ah]) A chloris C A Chloris C ah klaw-reess C (To Chloris) C (poem by Théophile de Viau [tay- aw-feel duh veeo] set to music by Reynaldo Hahn [ray-NAHL-doh HAHN]) A deux danseuses C ah dö dah6-söz C (poem by Voltaire [vawl-tehr] set to music by Jacques Chailley [zhack shahee-yee]) A dur C A Dur C AHAH DOOR C (key of A major, German designation) A finisca e per sempre C ah fee-NEE-skah ay payr SAYM-pray C (excerpt from the opera Orfeo ed Euridice [ohr-FAY-o ayd ayoo-ree-DEE-chay]; music by Christoph Willibald von Gluck [KRIH-stawf VILL-lee-bahlt fawn GLÔÔK] and libretto by Ranieri de’ Calzabigi [rah- neeAY-ree day kahl-tsah-BEE-jee]) A globo veteri C AH GLO-bo vay-TAY-ree C (When from primeval mass) C (excerpt from -

Decca Discography

DECCA DISCOGRAPHY >>V VIENNA, Austria, Germany, Hungary, etc. The Vienna Philharmonic was the jewel in Decca’s crown, particularly from 1956 when the engineers adopted the Sofiensaal as their favoured studio. The contract with the orchestra was secured partly by cultivating various chamber ensembles drawn from its membership. Vienna was favoured for symphonic cycles, particularly in the mid-1960s, and for German opera and operetta, including Strausses of all varieties and Solti’s “Ring” (1958-65), as well as Mackerras’s Janá ček (1976-82). Karajan recorded intermittently for Decca with the VPO from 1959-78. But apart from the New Year concerts, resumed in 2008, recording with the VPO ceased in 1998. Outside the capital there were various sessions in Salzburg from 1984-99. Germany was largely left to Decca’s partner Telefunken, though it was so overshadowed by Deutsche Grammophon and EMI Electrola that few of its products were marketed in the UK, with even those soon relegated to a cheap label. It later signed Harnoncourt and eventually became part of the competition, joining Warner Classics in 1990. Decca did venture to Bayreuth in 1951, ’53 and ’55 but wrecking tactics by Walter Legge blocked the release of several recordings for half a century. The Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra’s sessions moved from Geneva to its home town in 1963 and continued there until 1985. The exiled Philharmonia Hungarica recorded in West Germany from 1969-75. There were a few engagements with the Bavarian Radio in Munich from 1977- 82, but the first substantial contract with a German symphony orchestra did not come until 1982. -

Studia Musica – 1 – 2017

MUSICA 1/2017 STUDIA UNIVERSITATIS BABEŞ-BOLYAI MUSICA 1/2017 JUNE REFEREES: Acad. Dr. István ALMÁSI, Folk Music Scientific Researcher, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, Member of the Hungarian Academy of Arts – Budapest, Hungary Univ. Prof. Dr. István ANGI, „Gh. Dima” Music Academy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Univ. Prof. Dr. Gabriel BANCIU, „Gh. Dima” Music Academy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Univ. Prof. Dr. Habil. Stela DRĂGULIN, Transylvania University of Braşov, Romania Univ. Prof. Dr. Habil. Noémi MACZELKA DLA, Pianist, Head of the Arts Institute and the Department of Music Education, University of Szeged, "Juhász Gyula" Faculty of Education, Hungary College Prof. Dr. Péter ORDASI, University of Debrecen, Faculty of Music, Hungary Univ. Prof. Dr. Pavel PUŞCAŞ, „Gh. Dima” Music Academy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Univ. Prof. Dr. Valentina SANDU-DEDIU, National University of Music, Bucharest, Romania Univ. Prof. Dr. Ilona SZENIK, „Gh. Dima” Music Academy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Acad. Univ. Prof. Dr. Eduard TERÉNYI, „Gh. Dima” Music Academy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, Member of the Hungarian Academy of Arts – Budapest, Hungary Acad. College Associate Prof. Dr. Péter TÓTH, DLA, University of Szeged, Dean of the Faculty of Musical Arts, Hungary, Member of the Hungarian Academy of Arts – Budapest, Hungary EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Associate Prof. Dr. Gabriela COCA, Babeş-Bolyai University, Reformed Theology and Musical Pedagogy Department, Cluj-Napoca, Romania PERMANENT EDITORIAL BOARD: Associate Prof. Dr. Éva PÉTER, Babeş-Bolyai University, Reformed Theology and Musical Pedagogy Department, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Lecturer Prof. Dr. Miklós FEKETE, Babeş-Bolyai University, Reformed Theology and Musical Pedagogy Department, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Assist. Prof. Dr. Adél FEKETE, Babeş-Bolyai University, Reformed Theology and Musical Pedagogy Department, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Assist. -

Programme Calendar

PROGRAMME CALENDAR Dear Reader, First and foremost, let me allay any fears that the anniversary of Shakespeare’s dates that should be marked on the calendar in red letters. Our 120 Hungarian artists will also be joined in song by names birth in 2014 passed us by here at the Opera House. It’s just that we had other like Gruberova, D’Arcangelo, Herlitzius, Kampe, Kwangchul, Watson, Tómasson, Konieczny, Neil, Chacón-Cruz, Valenti, things to do: the festival of the Strauss repertoire that was many years in the Maestri, Ataneli and Demuro, while top domestic conductors and their world-renowned peers will be passing the baton making and the exploration of the theme of Faust, for instance. Now that the to star names like Plasson, Pido, Badea and Steinberg, and the 2nd Iván Nagy International Ballet Gala will once again 400th anniversary of the extraordinarily multi-faceted playwright is approaching, welcome the greats of the global ballet scene – this is because, ever since the times of Erkel and Mahler, the Hungarian State the opportunity has arisen for Hungary’s most prestigious cultural institution to Opera has proclaimed the joyful place among equals occupied by Hungarian culture. mobilise its enormous creative powers in service of exploring the remarkably broad literature of the Shakespearean universe. Broken down into figures, the 2015/2016 season of the Hungarian State Opera will see 500 full-scale performances with 33 new productions and 45 from the repertoire, a total of 100 concerts, chamber performances, gala and other events, some 200 This will not be a commemoration of a death; how could it be? We come to pay children’s programmes, 600 tours of the building and more than 1,100 ambassadorial presentations.