Study Commentary on 1 Kings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solomon's Legacy

Solomon’s Legacy Divided Kingdom Image from: www.lightstock.com Solomon’s Last Days -1 Kings 11 Image from: www.lightstock.com from: Image ➢ God raises up adversaries to Solomon. 1 Kings 11:14 14 Then the LORD raised up an adversary to Solomon, Hadad the Edomite; he was of the royal line in Edom. 1 Kings 11:23-25 23 God also raised up another adversary to him, Rezon the son of Eliada, who had fled from his lord Hadadezer king of Zobah. 1 Kings 11:23-25 24 He gathered men to himself and became leader of a marauding band, after David slew them of Zobah; and they went to Damascus and stayed there, and reigned in Damascus. 1 Kings 11:23-25 25 So he was an adversary to Israel all the days of Solomon, along with the evil that Hadad did; and he abhorred Israel and reigned over Aram. Solomon’s Last Days -1 Kings 11 Image from: www.lightstock.com from: Image ➢ God tells Jeroboam that he will be over 10 tribes. 1 Kings 11:26-28 26 Then Jeroboam the son of Nebat, an Ephraimite of Zeredah, Solomon’s servant, whose mother’s name was Zeruah, a widow, also rebelled against the king. 1 Kings 11:26-28 27 Now this was the reason why he rebelled against the king: Solomon built the Millo, and closed up the breach of the city of his father David. 1 Kings 11:26-28 28 Now the man Jeroboam was a valiant warrior, and when Solomon saw that the young man was industrious, he appointed him over all the forced labor of the house of Joseph. -

HEPTADIC VERBAL PATTERNS in the SOLOMON NARRATIVE of 1 KINGS 1–11 John A

HEPTADIC VERBAL PATTERNS IN THE SOLOMON NARRATIVE OF 1 KINGS 1–11 John A. Davies Summary The narrative in 1 Kings 1–11 makes use of the literary device of sevenfold lists of items and sevenfold recurrences of Hebrew words and phrases. These heptadic patterns may contribute to the cohesion and sense of completeness of both the constituent pericopes and the narrative as a whole, enhancing the readerly experience. They may also serve to reinforce the creational symbolism of the Solomon narrative and in particular that of the description of the temple and its dedication. 1. Introduction One of the features of Hebrew narrative that deserves closer attention is the use (consciously or subconsciously) of numeric patterning at various levels. In narratives, there is, for example, frequently a threefold sequence, the so-called ‘Rule of Three’1 (Samuel’s three divine calls: 1 Samuel 3:8; three pourings of water into Elijah’s altar trench: 1 Kings 18:34; three successive companies of troops sent to Elijah: 2 Kings 1:13), or tens (ten divine speech acts in Genesis 1; ten generations from Adam to Noah, and from Noah to Abram; ten toledot [‘family accounts’] in Genesis). One of the numbers long recognised as holding a particular fascination for the biblical writers (and in this they were not alone in the ancient world) is the number seven. Seven 1 Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folktale (rev. edn; Austin: University of Texas Press, 1968; tr. from Russian, 1928): 74; Christopher Booker, The Seven Basic Plots of Literature: Why We Tell Stories (London: Continuum, 2004): 229-35; Richard D. -

Septuagint Vs. Masoretic Text and Translations of the Old Testament

#2 The Bible: Origin & Transmission November 30, 2014 Septuagint vs. Masoretic Text and Translations of the Old Testament The Septuagint (Greek translation of the Old Testament) captured the Original Hebrew Text before Mistakes crept in. Psalm 119:89 Forever, O LORD, Your word is settled in heaven. 2 Timothy 3:16 All Scripture is inspired breathed by God 2 Peter 1:20-21 No prophecy of Scripture is a matter of one's own interpretation, for no prophecy was ever made by an act of human will, but men moved by the but men carried along by Holy Spirit spoke from God. Daniel 8:5 While I was observing, behold, a male goat was coming from the west over the surface of the whole earth without touching the ground 1 Kings 4:26 Solomon had 40,000 stalls of horses for his chariots, and 12,000 horsemen. 2 Chronicles 9:25 Now Solomon had 4,000 stalls for horses and chariots and 12,000 horsemen, 1 Kings 5:15-16 Now Solomon had 70,000 transporters, and 80,000 hewers of stone in the mountains, besides Solomon's 3,300 chief deputies who were over the project and who ruled over the people who were doing the work. 2 Chronicles 2:18 He appointed 70,000 of them to carry loads and 80,000 to quarry stones in the mountains and 3,600 supervisors . Psalm 22:14 (Masoretic) I am poured out like water, and all my bones are out of joint; My heart is like wax; it is melted within me. -

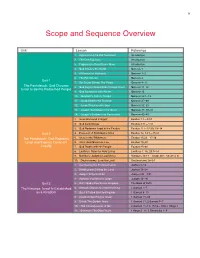

Scope and Sequence Overview

9 Scope and Sequence Overview Unit Lesson Reference 1. Approaching the Old Testament Introduction 2. The One Big Story Introduction 3. Preparing to Read God's Word Introduction 4. God Creates the World Genesis 1 5. A Mission for Humanity Genesis 1–2 6. The Fall into Sin Genesis 3 Unit 1 7. Sin Grows Worse: The Flood Genesis 4–11 The Pentateuch: God Chooses 8. God Begins Redemption through Israel Genesis 11–12 Israel to Be His Redeemed People 9. God Covenants with Abram Genesis 15 10. Abraham's Faith Is Tested Genesis 22:1–19 11. Jacob Inherits the Promise Genesis 27–28 12. Jacob Wrestles with God Genesis 32–33 13. Joseph: God Meant It for Good Genesis 37; 39–41 14. Joseph's Brothers Are Reconciled Genesis 42–45 1. Israel Enslaved in Egypt Exodus 1:1—2:10 2. God Calls Moses Exodus 2:11—4:31 3. God Redeems Israel in the Exodus Exodus 11:1–12:39; 13–14 Unit 2 4. Passover: A Redemption Meal Exodus 12; 14:1—15:21 The Pentateuch: God Redeems 5. Israel in the Wilderness Exodus 15:22—17:16 Israel and Expects Covenant 6. Sinai: God Gives His Law Exodus 19–20 Loyalty 7. God Dwells with His People Exodus 25–40 8. Leviticus: Rules for Holy Living Leviticus 1; 16; 23:9–14 9. Numbers: Judgment and Mercy Numbers 13:17—14:45; 20:1–13; 21:4–8 10. Deuteronomy: Love the Lord! Deuteronomy 28–34 1. Conquering the Promised Land Joshua 1–12 2. -

Othb6313 Hebrew Exegesis: 1 & 2 Kings

OTHB6313 HEBREW EXEGESIS: 1 & 2 KINGS Dr. R. Dennis Cole Fall 2015 Campus Box 62 3 Hours (504)282-4455 x 3248 Email: [email protected] Seminary Mission Statement: The mission of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary is to equip leaders to fulfill The Great Commission and The Great Commandments through the local church and its ministries. Course Description: This course combines an overview of 1 & 2 Kings and its place in the Former Prophets with an in-depth analysis of selected portions of the Hebrew text. Primary attention will be given to the grammatical, literary, historical, and theological features of the text. The study will include a discussion of the process leading to hermeneutical goals of teaching and preaching. Student Learning Outcomes: Upon the successful completion of this course the student will have demonstrated a proper knowledge of and an ability to use effectively in study, teaching and preaching: 1. The overall literary structure and content of 1 & 2 Kings. 2. The major theological themes and critical issues in the books. 3. The Hebrew text of 1 & 2 Kings. 4. Hebrew syntax and literary stylistics. NOBTS Core Values Addressed: Doctrinal Integrity: Knowledge and Practice of the Word of God Characteristic Excellence: Pursuit of God’s Revelation with Diligence Spiritual Vitality: Transforming Power of God’s Word Mission Focus: We are here to change the world by fulfilling the Great Commission and the Great Commandments through the local church and its ministries. This is the 2015-16 core value focus. Textbooks: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. 1 Kings, Simon DeVries (Word Biblical Commentary) 2 Kings, T.R. -

1 Kings 14 Jeroboam’S Decline

1 Kings 14 Jeroboam’s Decline JEROBOAM – King of Israel (20 yrs) REHOBOAM – King of Judah (17 yrs) Former servant of Solomon Son of Solomon Northern 10 tribes Southern 2 tribes (Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, (Judah, Benjamin) Asher, Issachar, Zebulun, Joseph) Capital City: Samaria Capital City: Jerusalem Evil Walked with God (3 yrs) Established: Built up: - counterfeit temple in Samaria - Levitical priesthood (many moved to - idol worship (golden calf cult) Judah) - high places for foreign gods - multiple cities for defense - strong fortresses Denounced: - commanders - Yahweh’s deliverance from Egypt - supplies Abolished/changed: Acted Wisely: - Levitical priesthood - placed sons in districts - holy feast days - supplied ample provisions - found wives for his sons God’s Instrument for punishing Solomon’s sins & judging Israel Abandoned the Ways of God - became subjected to Egyptian army - lost temple in Jerusalem Humbled himself -not totally destroyed Did Evil - turned from God - nation slid into moral decay 1 Prophecy Against Jeroboam 14 At that time Abijah the son of Jeroboam fell sick. 2 And Jeroboam said to his wife, “Arise, and disguise yourself, that it not be known that you are the wife of Jeroboam, and go to Shiloh. Behold, Ahijah the prophet is there, who said of me that I should be king over this people. 3 Take with you ten loaves, some cakes, and a jar of honey, and go to him. He will tell you what shall happen to the child.” 4 Jeroboam's wife did so. She arose and went to Shiloh and came to the house of Ahijah. Now Ahijah could not see, for his eyes were dim because of his age. -

OLD TESTAMENT SURVEY Lesson 32 the Divided Monarchy – Civil War Hebrew Review Aleph - Mem

OLD TESTAMENT SURVEY Lesson 32 The Divided Monarchy – Civil War Hebrew review Aleph - Mem I recently had an opportunity to read a rather lengthy write up of some lawsuits we handled. The underlying issues had captured the interest of a reporter turned author, and she had written up her assessment having interviewed many of the key players in the litigation. As I read an early version of her work product, I was interested in what others said about the cases. We had won several of the underlying lawsuits, but had lost one as well. Her focus on the one we lost included some comments by others, including my friends, on why we lost. It was interesting to read what others said about my handling of that case! Evidently, I am not the only one she gave an advance copy to, because I got an email this week from one of my friendly colleagues. In the email, my friend wrote, Some quotes don't sound like me…She did have a passage where it sounded like I challenged your handling of the case. Anytime I saw you in the courtroom I thought you did an extraordinary job - my background and training puts me in no position to question your strategy. My friend was concerned over what my reaction would be when reading his critique of my decisions! I will admit, the criticism stung. I do not like losing, and I really do not like people opining that my failures might be my own fault! I wrote my friend a reply to reassure him that his criticism had not harmed our friendship. -

Prophecy and Enervation in the American Political Tradition

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Right Without Might: Prophecy and Enervation in the American Political Tradition Jonathan Keller Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/358 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] RIGHT WITHOUT MIGHT: PROPHECY AND ENERVATION IN THE AMERICAN POLITICAL TRADITION by JONATHAN J. KELLER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 JONATHAN J. KELLER All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. PROFESSOR COREY ROBIN _______________ __________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee PROFESSOR ALYSON COLE _______________ __________________________________________ Date Executive Officer PROFESSOR ANDREW J. POLSKY PROFESSOR THOMAS HALPER PROFESSOR BRYAN TURNER PROFESSOR NICHOLAS XENOS __________________________________________ Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract RIGHT WITHOUT MIGHT: PROPHECY AND ENERVATION IN THE AMERICAN POLITICAL TRADITION by JONATHAN J. KELLER Adviser: Professor Corey Robin This dissertation examines the ways Old Testament prophecy has influenced American political thought and rhetoric. Although political scientists have long recognized the impact of the Scriptures on the ways Americans express and think about themselves, they have misunderstood this important part of America’s political tradition. -

The Life and Psalms of David a Man After God’S Heart

These study lessons are for individual or group Bible study and may be freely copied or distributed for class purposes. Please do not modify the material or distribute partially. Under no circumstances are these lessons to be sold. Comments are welcomed and may be emailed to [email protected]. The Life and Psalms of David A Man After God’s Heart Curtis Byers 2015 The Life and Psalms of David Introduction The life of David is highly instructive to all who seek to be a servant of God. Although we cannot relate to the kingly rule of David, we can understand his struggle to live his life under the mighty hand of God. His success in that struggle earned him the honor as “a man after God’s own heart” (Acts 13:22). The intent of David’s heart is not always apparent by simply viewing his life as recorded in the books of Samuel. It is, however, abundantly clear by reading his Psalms. The purpose of this class will be to study the Psalms of David in the context of his life. David was a shepherd, musician, warrior, poet, friend, king, and servant. Although the events of David’s life are more dramatic than those in our lives, his battle with avoiding the wrong and seeking the right is the same as ours. Not only do his victories provide valuable lessons for us, we can also learn from his defeats. David had his flaws, but it would be a serious misunderstanding for us to justify our flaws because David had his. -

What Did King Josiah Reform?

Chapter 17 What Did King Josiah Reform? Margaret Barker King Josiah changed the religion of Israel in 623 BC. According to the Old Testament account in 2 Kings 23, he removed all manner of idolatrous items from the temple and purified his kingdom of Canaanite practices. Temple vessels made for Baal, Asherah, and the host of heaven were removed, idolatrous priests were deposed, the Asherah itself was taken from the temple and burned, and much more besides. An old law book had been discovered in the temple, and this had prompted the king to bring the religion of his kingdom into line with the requirements of that book (2 Kings 22:8–13; 2 Chronicles 34:14–20).1 There could be only one temple, it stated, and so all other places of sacrificial worship had to be destroyed (Deuteronomy 12:1–5). The law book is easily recognizable as Deuteronomy, and so King Josiah’s purge is usually known as the Deuteronomic reform of the temple. In 598 BC, twenty-five years after the work of Josiah, Jerusalem was attacked by the Babylonians under King Nebuchadnezzar (2 Kings 24:10– 16; 25:1–9); eleven years after the first attack, they returned to destroy the city and the temple (586 BC). Refugees fled south to Egypt, and we read in the book of Jeremiah how they would not accept the prophet’s interpretation of the disaster (Jeremiah 44:16–19). Jeremiah insisted that Jerusalem had fallen because of the sins of her people, but the refugees said it had fallen because of Josiah. -

WHY BARZILLAI of GILEAD (1 KINGS 2:7)? NARRATIVE ART and the HERMENEUTICS of SUSPICION in 1 KINGS 1-2 Iain W

Tyndale Bulletin 46.1 (1995) 103-116. WHY BARZILLAI OF GILEAD (1 KINGS 2:7)? NARRATIVE ART AND THE HERMENEUTICS OF SUSPICION IN 1 KINGS 1-2 Iain W. Provan Summary Even if one remains uneasy about the precise direction in which much recent scholarship on biblical narrative has been moving, it is the case that much can be learned from the kind of approaches which have been developed. This paper argues, for example, that the author of 1 Kings 1-2 invites the reader to employ a ‘hermeneutic of suspicion’ in relation to his story by the artful way in which he tells it; and that the employment of such a hermeneutic enables a deeper grasp of what the story is about than would otherwise be possible. I. Introduction These are interesting times for those who are concerned with the interpretation of biblical texts, particularly Hebrew narrative texts. Old certainties are under attack. New revolutionaries clamber over the barricades, pronouncing those only recently considered (and considering themselves) as radicals to be, in fact, boringly conservative and quite passé. It seems just a blink of the eye ago, for example, that the average commentator on Kings thought it an important part of his task to tell his readers quite a bit about the sources from which the book might have been constructed and the editors who might successively have worked upon it. Of the existence of such sources and editors there was really no doubt, even if there was much disagreement about the details. It was simply accepted that there was a greater or lesser degree of incoherence in the text—inconsistencies, repetitions, variations in style and language, and so on—features unexpected, it 104 TYNDALE BULLETIN 46.1 (1995) was said, in the work of a single author. -

Kings, by Robert Vannoy, Lecture 8

1 Dr. Robert Vannoy: Kings, Lecture 8 © 2012, Dr. Robert Vannoy, Dr. Perry Phillips, Ted Hildebrandt We finished Roman numeral “I” last week which was “The United Kingdom under Solomon, Chapters 1-11.” So that brings us to Roman numeral “II” on the outlines I gave you, which is “The Divided Kingdom before Jehu.” The kingdom divided, as you know, in 931 B.C. The revolution of Jehu, where he wiped out the house of Ahab, is 841 B.C. so it’s approximately a hundred year period, 931-841 B.C. which we’ll look at under Roman numeral “II.” Capital “A” is “The Disruption” and “1” is “Background.” You read the section in 1 Kings as well as in the Expositor’s Bible commentary. But let me just mention by way of background, that that disruption is not something that happened without any precedence. In other words, there were factors involved that led to that disruption that had been around for some time. If you go back to early Israel’s history in the land of Canaan, you remember the agreement that Joshua made with the Gibeonites that came to him representing themselves as from a foreign land. That’s in Joshua chapter 9. Joshua concluded a treaty with them, which meant that the Israelites really could not carry out the command of the LORD to destroy these people because they had sworn in the name of the Lord that they would not do that. But that meant that right there in the heart of Canaan, you had these Gibeonites and the others that were permitted to remain as a foreign element in the land.