Aftermath of the Holocaust and Genocides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Issue in Friedrich Gorenstein's Writing

JEWISH ISSUE IN FRIEDRICH GORENSTEIN’S WRITING Elina Vasiljeva, Dr. philol. Daugavpils University/Institute of Comparative Studies , Latvia Abstract: The paper discusses the specific features in the depiction of the Jewish issue in the writings by Friedrich Gorenstein.The nationality of Gorenstein is not hard to define, while his writing is much more ambiguous to classify in any national tradition. The Jewish theme is undoubtedly the leading one in his writing. Jewish issue is a part of discussions about private fates, the history of Russia, the Biblical sense of the existence of the whole humankind. Jewish subject matter as such appears in all of his works and these are different parts of a single system. Certainly, Jewish issues partially differ in various literary works by Gorenstein but implicitly they are present in all texts and it is not his own intentional wish to emphasize the Jewish issue: Jewish world is a part of the universe, it is not just the tragic fate of a people but a test of humankind for humanism, for the possibility to become worthy of the supreme redemption. The Jewish world of Gorenstein is a mosaic world in essence. The sign of exile and dispersal is never lifted. Key Words: Jewish , Biblical, anti-Semitism Introduction The phenomenon of the reception of one culture in the framework of other cultures has been known since the antiquity. Since the ancient times, intercultural dialogue has been implemented exactly in this form. And this reception of another culture does not claim to be objective. On the contrary, it reflects not the peculiarities of the culture perceived, but rather the particularities of artistic consciousness of the perceiving culture. -

Poetry Sampler

POETRY SAMPLER 2020 www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature: An Anthology Edited by Maxim D. Shrayer New York Elegies: Ukrainian Poems on the City Edited by Ostap Kin Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine Edited by Oksana Maksymchuk & Max Rosochinsky The White Chalk of Days: The Contemporary Ukrainian Literature Series Anthology Compiled and edited by Mark Andryczyk www.academicstudiespress.com Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature An Anthology Edited, with Introductory Essays by Maxim D. Shrayer Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiv Note on Transliteration, Spelling of Names, and Dates xvi Note on How to Use This Anthology xviii General Introduction: The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature Maxim D. Shrayer xxi Early Voices: 1800s–1850s 1 Editor’s Introduction 1 Leyba Nevakhovich (1776–1831) 3 From Lament of the Daughter of Judah (1803) 5 Leon Mandelstam (1819–1889) 11 “The People” (1840) 13 Ruvim Kulisher (1828–1896) 16 From An Answer to the Slav (1849; pub. 1911) 18 Osip Rabinovich (1817–1869) 24 From The Penal Recruit (1859) 26 Seething Times: 1860s–1880s 37 Editor’s Introduction 37 Lev Levanda (1835–1888) 39 From Seething Times (1860s; pub. 1871–73) 42 Grigory Bogrov (1825–1885) 57 “Childhood Sufferings” from Notes of a Jew (1863; pub. 1871–73) 59 vi Table of Contents Rashel Khin (1861–1928) 70 From The Misfit (1881) 72 Semyon Nadson (1862–1887) 77 From “The Woman” (1883) 79 “I grew up shunning you, O most degraded nation . .” (1885) 80 On the Eve: 1890s–1910s 81 Editor’s Introduction 81 Ben-Ami (1854–1932) 84 Preface to Collected Stories and Sketches (1898) 86 David Aizman (1869–1922) 90 “The Countrymen” (1902) 92 Semyon Yushkevich (1868–1927) 113 From The Jews (1903) 115 Vladimir Jabotinsky (1880–1940) 124 “In Memory of Herzl” (1904) 126 Sasha Cherny (1880–1932) 130 “The Jewish Question” (1909) 132 “Judeophobes” (1909) 133 S. -

1 Spring 2012 Prof. Jochen Hellbeck [email protected] Van Dyck Hall 002F Office Hours: M 3:30-5:00 and by Appointment Hi

Spring 2012 Prof. Jochen Hellbeck [email protected] Van Dyck Hall 002F Office hours: M 3:30-5:00 and by appointment History 510:375 -- 20 th Century Russia (M/W 6:10-7:30 CA A4) The history of 20 th century Russia, as well as the world, was decisively shaped by the Revolution of 1917 and the Soviet experiment. For much of the century the Soviet Union represented the alternative to the West. When the Bolsheviks came to power in 1917 they were committed to remake the country and its people according to their socialist vision. This course explores the effects of the Soviet project—rapid modernization and ideological transformation—on a largely agrarian, “backward” society. We will consider the hopes and ideals generated by the search for a new and better world, and we will address the violence and devastation caused by the pursuit of utopian politics. Later parts of the course will trace the gradual erosion of Communist ideology in the wake of Stalin's death and follow the regime’s crisis until the spectacular breakup of the empire in 1991. Throughout the course, we will emphasize how the revolution was experienced by a range of people – Russians and non-Russians; men and women; artists and intellectuals, but also workers, soldiers, and peasants – and what it meant for them to live in the Soviet system in its different phases. To convey this perspective, the reading material includes a wide selection of personal accounts, fiction, artwork, films, which will be complemented by scholarly analyses. For a fuller statement of the learning goals pursued in this class, see More generally, see the History department statement on undergraduate learning goals: http://history.rutgers.edu/undergraduate/learning-goals The Communist age is now over. -

Crossing Central Europe

CROSSING CENTRAL EUROPE Continuities and Transformations, 1900 and 2000 Crossing Central Europe Continuities and Transformations, 1900 and 2000 Edited by HELGA MITTERBAUER and CARRIE SMITH-PREI UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press 2017 Toronto Buffalo London www.utorontopress.com Printed in the U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4426-4914-9 Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable-based inks. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Crossing Central Europe : continuities and transformations, 1900 and 2000 / edited by Helga Mitterbauer and Carrie Smith-Prei. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4426-4914-9 (hardcover) 1. Europe, Central – Civilization − 20th century. I. Mitterbauer, Helga, editor II. Smith-Prei, Carrie, 1975−, editor DAW1024.C76 2017 943.0009’049 C2017-902387-X CC-BY-NC-ND This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivative License. For permission to publish commercial versions please contact University of Tor onto Press. The editors acknowledge the financial assistance of the Faculty of Arts, University of Alberta; the Wirth Institute for Austrian and Central European Studies, University of Alberta; and Philixte, Centre de recherche de la Faculté de Lettres, Traduction et Communication, Université Libre de Bruxelles. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the -

War and Rape, Germany 1945

Lees-Knowles Lectures Cambridge 2002-3 Antony Beevor 2. War and Rape, Germany 1945 „Red Army soldiers don't believe in “individual liaisons” with German women‟, wrote the playwright Zakhar Agranenko in his diary when serving as an officer of marine infantry in East Prussia. „Nine, ten, twelve men at a time - they rape them on a collective basis‟. The Soviet armies advancing into East Prussia in January 1945, in huge, long columns were an extraordinary mixture of modern and mediaeval: tank troops in padded black helmets, Cossack cavalrymen on shaggy mounts with loot strapped to the saddle, Lend-Lease Studebakers and Dodges towing light field guns, and then a second echelon in horse- drawn carts. The variety of character among the soldiers was almost as great as their military equipment. There were freebooters who drank and raped quite shamelessly, and there were idealistic, austere Communists and members of the intelligentsia genuinely appalled by such behaviour. Beria and Stalin back in Moscow knew perfectly well what was going on from a number of detailed reports sent by generals commanding the NKVD rifle divisions in charge of rear area security. One stated that „many Germans declare that all German women in East Prussia who stayed behind were raped by Red Army soldiers‟. This opinion was presumably shared by the authorities, since if they had disagreed, they would have added the ritual formula: „This is a clear case of slander against the Red Army.‟ In fact numerous examples of gang rape were given in a number of other reports – „girls under eighteen and old women included‟. -

Lenin's Troubled Legacies: Bolshevism, Marxism, and the Russian Traditions

Lenin's Troubled Legacies: Bolshevism, Marxism, and the Russian Traditions by Vladimir Tismaneanu I will start with a personal confession: I have never visited the real Russia, so, in my case, there is indeed a situation where Russia is imagined. But, on the other hand, my both sisters were born in the USSR during World War II, where my parents were political refugees following the defeat of the Spanish Republic for which they fought as members of the International Brigades (my father, born in Bessarabia, i.e., in the Russian empire, lost his right arm at the age of 23 at the battle of the River Ebro; my mother, a medical student in Bucharest, worked as a nurse a the International Hospital in Barcelona, then, during the war, finished her medical studies at the Moscow Medical School no. 2, where she was a student of one of professor Kogan, later to be accused of murderous conspiracy in the doctors' trial). They all returned to Romania in March 1948, three years before I was born. So, though I never traveled to Russia, my memory, from the very early childhood was imbued with Russian images, symbols, songs, poems, fairy tales, and all the other elements that construct a child's mental universe. My eldest sister was born in Kuybishev (now Samara), where my mother was in evacuation, together with most of the Soviet government workers--she was a broadcaster for the Romanian service of Radio Moscow. My sister was born on November 25th, 1941 in an unheated school building, under freezing temperature, without any medical supplies, food, or milk. -

Download This Thesis As

THE UNIVERSITY OF NICOSIA VISIONS OF SPACE HABITATION: FROM FICTION TO REALITY A THESIS SUBMITED TO THE FACULTY OF ARCHITECTURE FOR THE PROFESSIONAL DIPLOMA DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE SUPERVISORS PROFESSOR SOLON XENOPOULOS PROFESSOR NIKOLAS PATSAVOS BY FARHAD PAKAN NICOSIA JANUARY 2012 Contents Acknowledgment 3 Abstract 4 Exhibits 5 Abbreviations and acronyms 7 1 Introduction 8 2 Visions of Space Exploration in the Films of Tarkovski and Kubrick 11 3 Life at the Extremes 23 3.1 Habitability and Life on Earth 23 3.1.1 The Halley VI Antarctic Research Centre 25 3.1.2 The Aquarius Underwater Laboratory 27 3.2 Offworld Human Settlements 31 3.2.1 The International Space Station (ISS) 33 3.2.2 The City as a Spaceship (CAAS) 38 4 Formation of a new Settlement 44 4.1 Toward the Earth’s Eight Continent 45 4.1.1 Early Attempts 46 1 4.1.2 HABOT BASE Architecture 52 4.2 Lunar Site Design 58 4.2.1 Perception of Lunar Urbanity 67 4.2.2 Learning from the Romans 70 5 Conclusion 75 References 78 2 Acknowledgments I wish to thank Prof. Xenopoulos, Prof. Patsavos and Prof. Menikou for helping me to outline and structure this paper and for their assistance with grammar and proper citation. 3 Abstract The purpose of this paper is to provide an analytic observation through the visions of space habitation. It will study how the adventurous way of thinking and imagination of the curious human about the future of its life within the extraterrestrial environment, became a stepping stone for studying and challenging of these extreme environments and the initiation of a brave new era in the history of humanity. -

Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier at the Congress of the Central Council of Jews in Germany in Berlin on 19 December 2019

Read the speech online: www.bundespraesident.de Page 1 of 5 Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier at the congress of the Central Council of Jews in Germany in Berlin on 19 December 2019 I now know the Hebrew word likrat. It means “to move towards one another”. I learned it from young Jewish people whom I just met with the President of the Central Council before the start of the event. These young people visit schools, where they meet non-Jewish pupils and explain their faith, answer questions and describe what being Jewish means to them. The documentary filmmaker and Grimme Prize laureate Britta Wauer reported on this project last year in one of her wonderful films. A great deal of warmth, enthusiasm, dedication and realism can be felt in this film. I also experience a similarly welcoming atmosphere here with you at the annual gathering of the Jewish community. Josef Schuster, ladies and gentlemen, thank you very much indeed for inviting me! I am delighted to be here with you today! And I am here in the firm conviction that it is the right time to be here! You all know the word likrat, to move towards one another. You will be familiar with this project and I imagine that you have also seen the film. I think it is a wonderful idea. It is both a beautiful and a simple way to put a face to one’s own faith, to move towards people of different faiths, to start a dialogue and to discover common ground. I think many people in our country, Jews and non-Jews alike, wish for likrat! But the path on which we move towards one another has become more arduous in recent years. -

Talking Fish: on Soviet Dissident Memoirs*

Talking Fish: On Soviet Dissident Memoirs* Benjamin Nathans University of Pennsylvania My article may appear to be idle chatter, but for Western sovietolo- gists at any rate it has the same interest that a fish would have for an ichthyologist if it were suddenly to begin to talk. ðAndrei Amalrik, Will the Soviet Union Survive until 1984? ½samizdat, 1969Þ All Soviet émigrés write ½or: make up something. Am I any worse than they are? ðAleksandr Zinoviev, Homo Sovieticus ½Lausanne, 1981Þ IfIamasked,“Did this happen?” I will reply, “No.” If I am asked, “Is this true?” Iwillsay,“Of course.” ðElena Bonner, Mothers and Daughters ½New York, 1991Þ I On July 6, 1968, at a party in Moscow celebrating the twenty-eighth birthday of Pavel Litvinov, two guests who had never met before lingered late into the night. Litvinov, a physics teacher and the grandson of Stalin’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs, Maxim Litvinov, had recently made a name for himself as the coauthor of a samizdat text, “An Appeal to World Opinion,” thathadgarneredwideattention inside and outside the Soviet Union. He had been summoned several times by the Committee for State Security ðKGBÞ for what it called “prophylactic talks.” Many of those present at the party were, like Litvinov, connected in one way or another to the dissident movement, a loose conglomeration of Soviet citizens who had initially coalesced around the 1966 trial of the writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel, seeking to defend civil rights inscribed in the Soviet constitution and * For comments on previous drafts of this article, I would like to thank the anonymous readers for the Journal of Modern History as well as Alexander Gribanov, Jochen Hell- beck, Edward Kline, Ann Komaromi, Eli Nathans, Sydney Nathans, Serguei Oushakine, Kevin M. -

The Management of Art in the Soviet Union1

Entremons. UPF Journal of World History. Número 7 (juny 2015) Thomas SANDERS The Management of Art in the Societ Union ■ Article] ENTREMONS. UPF JOURNAL OF WORLD HISTORY Universitat Pompeu Fabra|Barcelona Número 7 (juny 2015) www.entremons.org The Management of Art in the Soviet Union1 Thomas SANDERS US Naval Academy [email protected] Abstract The article examines the theory and practice of Soviet art management. The primary area of interest is cinematic art, although the aesthetic principles that governed film production also applied to the other artistic fields. Fundamental to an understanding of Soviet art management is the elucidation of Marxist-Leninist interpretation of the role of art as part of a society’s superstructure, and the contrast defined by Soviet Marxist-Leninists between “socialist” art (i.e., that of Soviet society) and the art of bourgeois, capitalist social systems. Moreover, this piece also explores the systems utilized to manage Soviet art production— the control and censorship methods and the material incentives. Keywords USSR, art, Marxism, socialist realism The culture, politics, and economics of art in the Soviet system differed in fundamental ways from the Western capitalist, and especially American, practice of art. The Soviet system of art was part and parcel of the Bolshevik effort aimed at nothing less than the creation of a new human type: the New Soviet Man (novyi sovetskii chelovek). The world of art in the Soviet Union was fashioned according to the Marxist understanding that art is part of the superstructure of a society. This interpretation was diametrically opposed to traditional Western views concerning art. -

Soviet Science Fiction Movies in the Mirror of Film Criticism and Viewers’ Opinions

Alexander Fedorov Soviet science fiction movies in the mirror of film criticism and viewers’ opinions Moscow, 2021 Fedorov A.V. Soviet science fiction movies in the mirror of film criticism and viewers’ opinions. Moscow: Information for all, 2021. 162 p. The monograph provides a wide panorama of the opinions of film critics and viewers about Soviet movies of the fantastic genre of different years. For university students, graduate students, teachers, teachers, a wide audience interested in science fiction. Reviewer: Professor M.P. Tselysh. © Alexander Fedorov, 2021. 1 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 1. Soviet science fiction in the mirror of the opinions of film critics and viewers ………………………… 4 2. "The Mystery of Two Oceans": a novel and its adaptation ………………………………………………….. 117 3. "Amphibian Man": a novel and its adaptation ………………………………………………………………….. 122 3. "Hyperboloid of Engineer Garin": a novel and its adaptation …………………………………………….. 126 4. Soviet science fiction at the turn of the 1950s — 1960s and its American screen transformations……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 130 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….… 136 Filmography (Soviet fiction Sc-Fi films: 1919—1991) ……………………………………………………………. 138 About the author …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 150 References……………………………………………………………….……………………………………………………….. 155 2 Introduction This monograph attempts to provide a broad panorama of Soviet science fiction films (including television ones) in the mirror of -

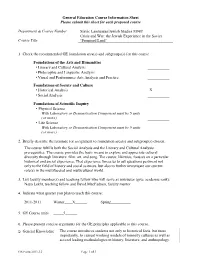

Slavic Lang M98T GE Form

General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Slavic Languages/Jewish Studies M98T Crisis and War: the Jewish Experience in the Soviet Course Title ‘Promised Land’ 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis X • Social Analysis Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. The course fulfills both the Social Analysis and the Literary and Cultural Analysis prerequisites. The course provides the basic means to explore and appreciate cultural diversity through literature, film, art, and song. The course, likewise, focuses on a particular historical and social experience. That experience forces us to ask questions pertinent not only to the field of history and social sciences, but also to further investigate our current role(s) in the multifaceted and multicultural world. 3. List faculty member(s) and teaching fellow who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Naya Lekht, teaching fellow and David MacFadyen, faculty mentor 4. Indicate what quarter you plan to teach this course: 2011-2011 Winter____X______ Spring__________ 5. GE Course units _____5______ 6. Please present concise arguments for the GE principles applicable to this course. General Knowledge The course introduces students not only to historical facts, but more importantly, to current working models of minority cultures as well as several leading methodologies in history, literature, and anthropology.