War and Rape, Germany 1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Spring 2012 Prof. Jochen Hellbeck [email protected] Van Dyck Hall 002F Office Hours: M 3:30-5:00 and by Appointment Hi

Spring 2012 Prof. Jochen Hellbeck [email protected] Van Dyck Hall 002F Office hours: M 3:30-5:00 and by appointment History 510:375 -- 20 th Century Russia (M/W 6:10-7:30 CA A4) The history of 20 th century Russia, as well as the world, was decisively shaped by the Revolution of 1917 and the Soviet experiment. For much of the century the Soviet Union represented the alternative to the West. When the Bolsheviks came to power in 1917 they were committed to remake the country and its people according to their socialist vision. This course explores the effects of the Soviet project—rapid modernization and ideological transformation—on a largely agrarian, “backward” society. We will consider the hopes and ideals generated by the search for a new and better world, and we will address the violence and devastation caused by the pursuit of utopian politics. Later parts of the course will trace the gradual erosion of Communist ideology in the wake of Stalin's death and follow the regime’s crisis until the spectacular breakup of the empire in 1991. Throughout the course, we will emphasize how the revolution was experienced by a range of people – Russians and non-Russians; men and women; artists and intellectuals, but also workers, soldiers, and peasants – and what it meant for them to live in the Soviet system in its different phases. To convey this perspective, the reading material includes a wide selection of personal accounts, fiction, artwork, films, which will be complemented by scholarly analyses. For a fuller statement of the learning goals pursued in this class, see More generally, see the History department statement on undergraduate learning goals: http://history.rutgers.edu/undergraduate/learning-goals The Communist age is now over. -

Film Film Film Film

Annette Michelson’s contribution to art and film criticism over the last three decades has been un- paralleled. This volume honors Michelson’s unique C AMERA OBSCURA, CAMERA LUCIDA ALLEN AND TURVEY [EDS.] LUCIDA CAMERA OBSCURA, AMERA legacy with original essays by some of the many film FILM FILM scholars influenced by her work. Some continue her efforts to develop historical and theoretical frame- CULTURE CULTURE works for understanding modernist art, while others IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION practice her form of interdisciplinary scholarship in relation to avant-garde and modernist film. The intro- duction investigates and evaluates Michelson’s work itself. All in some way pay homage to her extraordi- nary contribution and demonstrate its continued cen- trality to the field of art and film criticism. Richard Allen is Associ- ate Professor of Cinema Studies at New York Uni- versity. Malcolm Turvey teaches Film History at Sarah Lawrence College. They recently collaborated in editing Wittgenstein, Theory and the Arts (Lon- don: Routledge, 2001). CAMERA OBSCURA CAMERA LUCIDA ISBN 90-5356-494-2 Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson EDITED BY RICHARD ALLEN 9 789053 564943 MALCOLM TURVEY Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida: Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson Edited by Richard Allen and Malcolm Turvey Amsterdam University Press Front cover illustration: 2001: A Space Odyssey. Courtesy of Photofest Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 494 2 (paperback) nur 652 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2003 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Politics of History and Memory: the Russian Rape of Germany in Berlin

POLITICS OF HISTORY AND MEMORY 225 POLITICS OF HISTORY AND MEMORY: THE RUSSIAN RAPE OF GERMANY IN BERLIN, 1945 major hospitals ranged from 95,000 to 130,000; one physician estimated that out of 100,000 women raped in Berlin alone, 1 Krishna Ignalaga Thomas 10,000 died as a result, with a large majority committing suicide. With the sheer velocity of women raped by Soviet troops, it is The marching of the Russian Red Army into eastern Germany in incredible to discover its neglect by earlier seminal works, such the spring of 1945, at the close of World War II, was full of as that by John Erickson, who wrote Road to Berlin, and even promise and hope, a promise of a new era of peace in Europe William L. Shirer of Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. At the same and an end to political isolation and economic deprivation at time, the opening of the Russian State Military Archives and the home. In 1994, almost half a century later, the return of the Central Archive of the Ministry of Defense, a whole array of Soviet troops to the motherland signaled the surprising collapse primary source material and other information media are now of the Soviet Union and ultimately, the end of Soviet occupation open for scholars to understand this contest of brutality from and a reunified Germany. At the same time, however, the first, the German soldiers and then the repatriating Soviet Russians also left behind them a legacy of resentment and anger. troops. Much academic scholarship has focused on the years of Soviet Natalya Gesse, a Soviet war correspondent, gave a first‐hand occupation, 1945‐49, as being the most brutal on the Germans in estimation of Red Army’s activities, and stated that “The Russian the Eastern Zone than their counterparts in the West. -

Lenin's Troubled Legacies: Bolshevism, Marxism, and the Russian Traditions

Lenin's Troubled Legacies: Bolshevism, Marxism, and the Russian Traditions by Vladimir Tismaneanu I will start with a personal confession: I have never visited the real Russia, so, in my case, there is indeed a situation where Russia is imagined. But, on the other hand, my both sisters were born in the USSR during World War II, where my parents were political refugees following the defeat of the Spanish Republic for which they fought as members of the International Brigades (my father, born in Bessarabia, i.e., in the Russian empire, lost his right arm at the age of 23 at the battle of the River Ebro; my mother, a medical student in Bucharest, worked as a nurse a the International Hospital in Barcelona, then, during the war, finished her medical studies at the Moscow Medical School no. 2, where she was a student of one of professor Kogan, later to be accused of murderous conspiracy in the doctors' trial). They all returned to Romania in March 1948, three years before I was born. So, though I never traveled to Russia, my memory, from the very early childhood was imbued with Russian images, symbols, songs, poems, fairy tales, and all the other elements that construct a child's mental universe. My eldest sister was born in Kuybishev (now Samara), where my mother was in evacuation, together with most of the Soviet government workers--she was a broadcaster for the Romanian service of Radio Moscow. My sister was born on November 25th, 1941 in an unheated school building, under freezing temperature, without any medical supplies, food, or milk. -

A Film by MICHAEL HANEKE East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP BLOCK KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS

A film by MICHAEL HANEKE East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP BLOCK KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS Jeff Hill Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Jessica Uzzan Ziggy Kozlowski Lindsay Macik 853 7th Avenue, #3C 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-265-4373 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax X FILME CREATIVE POOL, LES FILMS DU LOSANGE, WEGA FILM, LUCKY RED present THE WHITE RIBBON (DAS WEISSE BAND) A film by MICHAEL HANEKE A SONY PICTURES CLASSICS RELEASE US RELEASE DATE: DECEMBER 30, 2009 Germany / Austria / France / Italy • 2H25 • Black & White • Format 1.85 www.TheWhiteRibbonmovie.com Q & A WITH MICHAEL HANEKE Q: What inspired you to focus your story on a village in Northern Germany just prior to World War I? A: I wanted to present a group of children on whom absolute values are being imposed. What I was trying to say was that if someone adopts an absolute principle, when it becomes absolute then it becomes inhuman. The original idea was a children’s choir, who want to make absolute principles concrete, and those who do not live up to them. Of course, this is also a period piece: we looked at photos of the period before World War I to determine costumes, sets, even haircuts. I wanted to describe the atmosphere of the eve of world war. There are countless films that deal with the Nazi period, but not the pre-period and pre-conditions, which is why I wanted to make this film. -

Heather Bigley, Phd Student, Writing a Dissertation on Film Studies

New German Cinema ENG 4135-13958 and GET 4523-15377 Barbara Mennel, Rothman Chair and Director, Center for the Humanities and the Public Sphere Office Hours: Mondays 11:00-12:00pm and by appointment Office: 200 Walker Hall (alternative office: 4219 TUR) Phone: (352) 392-0796; Email: [email protected] Meeting times: Class meetings: MWF 3 (9:35am-10:25) Room: TUR 2334 Screening: W 9-11 (beginning at 4:05pm) (attendance required) Room: Rolfs 115 Course objectives: In 1962, a group of young filmmakers at the Oberhausen Film Festival in West Germany boldly declared: “The old cinema is dead! We believe in a new cinema!” Out of this movement to overcome the 1950s legacies of fascism emerged a wave of filmmaking that became internationally known as New German Cinema. Its filmmakers were indebted to the student movement and a vision of filmmaking and distribution based on the notion of the director as auteur. This course offers a survey of the films from this brief period of enormous output and creativity, including the films by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Werner Herzog, Alexander Kluge, Helke Sander, Volker Schlöndorff, Margarethe von Trotta, and Wim Wenders. We will trace the influence of the women's movement on feminist aesthetics and situate the films’ negotiations of history and memory in postwar West German politics. Required reading: Julia Knight. New German Cinema: Images of a Generation. London: Wallflower Press, 2004. Eric Ames. Aguirre, The Wrath of God. London: BFI, 2016. Excerpts and articles in Canvas. All readings are also on reserve and accessible through the website of Library West and Canvas. -

MICHAEL HANEKE SONY WRMI 02Pressbook101909 Mise En Page 1 10/19/09 4:36 PM Page 2

SONY_WRMI_02Pressbook101909_Mise en page 1 10/19/09 4:36 PM Page 1 A film by MICHAEL HANEKE SONY_WRMI_02Pressbook101909_Mise en page 1 10/19/09 4:36 PM Page 2 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP BLOCK KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS Jeff Hill Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Jessica Uzzan Ziggy Kozlowski Lindsay Macik 853 7th Avenue, #3C 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-265-4373 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax SONY_WRMI_02Pressbook101909_Mise en page 1 10/19/09 4:36 PM Page 3 X FILME CREATIVE POOL, LES FILMS DU LOSANGE, WEGA FILM, LUCKY RED present THE WHITE RIBBON (DAS WEISSE BAND) A film by MICHAEL HANEKE A SONY PICTURES CLASSICS RELEASE US RELEASE DATE: DECEMBER 30, 2009 Germany / Austria / France / Italy • 2H25 • Black & White • Format 1.85 www.TheWhiteRibbonmovie.com SONY_WRMI_02Pressbook101909_Mise en page 1 10/19/09 4:36 PM Page 4 Q & A WITH MICHAEL HANEKE Q: What inspired you to focus your story on a village in Northern Germany just prior to World War I? A: Why do people follow an ideology? German fascism is the best-known example of ideological delusion. The grownups of 1933 and 1945 were children in the years prior to World War I. What made them susceptible to following political Pied Pipers? My film doesn’t attempt to explain German fascism. It explores the psychological preconditions of its adherents. What in people’s upbringing makes them willing to surrender their responsibilities? What in their upbringing makes them hate? Q. -

Talking Fish: on Soviet Dissident Memoirs*

Talking Fish: On Soviet Dissident Memoirs* Benjamin Nathans University of Pennsylvania My article may appear to be idle chatter, but for Western sovietolo- gists at any rate it has the same interest that a fish would have for an ichthyologist if it were suddenly to begin to talk. ðAndrei Amalrik, Will the Soviet Union Survive until 1984? ½samizdat, 1969Þ All Soviet émigrés write ½or: make up something. Am I any worse than they are? ðAleksandr Zinoviev, Homo Sovieticus ½Lausanne, 1981Þ IfIamasked,“Did this happen?” I will reply, “No.” If I am asked, “Is this true?” Iwillsay,“Of course.” ðElena Bonner, Mothers and Daughters ½New York, 1991Þ I On July 6, 1968, at a party in Moscow celebrating the twenty-eighth birthday of Pavel Litvinov, two guests who had never met before lingered late into the night. Litvinov, a physics teacher and the grandson of Stalin’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs, Maxim Litvinov, had recently made a name for himself as the coauthor of a samizdat text, “An Appeal to World Opinion,” thathadgarneredwideattention inside and outside the Soviet Union. He had been summoned several times by the Committee for State Security ðKGBÞ for what it called “prophylactic talks.” Many of those present at the party were, like Litvinov, connected in one way or another to the dissident movement, a loose conglomeration of Soviet citizens who had initially coalesced around the 1966 trial of the writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel, seeking to defend civil rights inscribed in the Soviet constitution and * For comments on previous drafts of this article, I would like to thank the anonymous readers for the Journal of Modern History as well as Alexander Gribanov, Jochen Hell- beck, Edward Kline, Ann Komaromi, Eli Nathans, Sydney Nathans, Serguei Oushakine, Kevin M. -

The Management of Art in the Soviet Union1

Entremons. UPF Journal of World History. Número 7 (juny 2015) Thomas SANDERS The Management of Art in the Societ Union ■ Article] ENTREMONS. UPF JOURNAL OF WORLD HISTORY Universitat Pompeu Fabra|Barcelona Número 7 (juny 2015) www.entremons.org The Management of Art in the Soviet Union1 Thomas SANDERS US Naval Academy [email protected] Abstract The article examines the theory and practice of Soviet art management. The primary area of interest is cinematic art, although the aesthetic principles that governed film production also applied to the other artistic fields. Fundamental to an understanding of Soviet art management is the elucidation of Marxist-Leninist interpretation of the role of art as part of a society’s superstructure, and the contrast defined by Soviet Marxist-Leninists between “socialist” art (i.e., that of Soviet society) and the art of bourgeois, capitalist social systems. Moreover, this piece also explores the systems utilized to manage Soviet art production— the control and censorship methods and the material incentives. Keywords USSR, art, Marxism, socialist realism The culture, politics, and economics of art in the Soviet system differed in fundamental ways from the Western capitalist, and especially American, practice of art. The Soviet system of art was part and parcel of the Bolshevik effort aimed at nothing less than the creation of a new human type: the New Soviet Man (novyi sovetskii chelovek). The world of art in the Soviet Union was fashioned according to the Marxist understanding that art is part of the superstructure of a society. This interpretation was diametrically opposed to traditional Western views concerning art. -

Women and War in the German Cultural Imagination

Conquering Women: Women and War in the German Cultural Imagination Edited by Hillary Collier Sy-Quia and Susanne Baackmann Description: This volume, focused on how women participate in, suffer from, and are subtly implicated in warfare raises the still larger questions of how and when women enter history, memory, and representation. The individual essays, dealing with 19th and mostly 20th century German literature, social history, art history, and cinema embody all the complexities and ambiguities of the title “Conquering Women.” Women as the mothers of current and future generations of soldiers; women as combatants and as rape victims; women organizing against war; and violence against women as both a weapon of war and as the justification for violent revenge are all represented in this collection of original essays by rising new scholars of feminist theory and German cultural studies. RESEARCH SERIES / NUMBER 104 Conquering Women: Women and War in the German Cultural Imagination X Hilary Collier Sy-Quia and Susanne Baackmann, Editors UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conquering women : women and war in the German cultural imagination / Hilary Collier Sy-Quia and Susanne Baackmann, editors. p. cm — (Research series ; no. 104) Papers from the 5th Annual Interdisciplinary German Studies Con- ference held at the University of California, Berkeley, March 1997. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-87725-004-9 1. German literature—History and criticism—Congresses. 2. Women in literature—Congresses. 3. War in literature—Congresses. 4. Violence in literature—Congresses. 5. Art, Modern—20th century—Germany— Congresses. 6. Women in art—Congresses. 7. -

Slavic Lang M98T GE Form

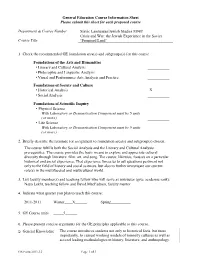

General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Slavic Languages/Jewish Studies M98T Crisis and War: the Jewish Experience in the Soviet Course Title ‘Promised Land’ 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis X • Social Analysis Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. The course fulfills both the Social Analysis and the Literary and Cultural Analysis prerequisites. The course provides the basic means to explore and appreciate cultural diversity through literature, film, art, and song. The course, likewise, focuses on a particular historical and social experience. That experience forces us to ask questions pertinent not only to the field of history and social sciences, but also to further investigate our current role(s) in the multifaceted and multicultural world. 3. List faculty member(s) and teaching fellow who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Naya Lekht, teaching fellow and David MacFadyen, faculty mentor 4. Indicate what quarter you plan to teach this course: 2011-2011 Winter____X______ Spring__________ 5. GE Course units _____5______ 6. Please present concise arguments for the GE principles applicable to this course. General Knowledge The course introduces students not only to historical facts, but more importantly, to current working models of minority cultures as well as several leading methodologies in history, literature, and anthropology. -

A Film by MICHAEL HANEKE DP RB - Anglais - VL 12/05/09 10:46 Page 2

DP RB - anglais - VL 12/05/09 10:46 Page 1 A film by MICHAEL HANEKE DP RB - anglais - VL 12/05/09 10:46 Page 2 X FILME CREATIVE POOL, LES FILMS DU LOSANGE, WEGA FILM, LUCKY RED present THE WHITE RIBBON (DAS WEISSE BAND) PRESS WOLFGANG W. WERNER PUBLIC RELATIONS phone: +49 89 38 38 67 0 / fax +49 89 38 38 67 11 [email protected] in Cannes: Wolfgang W. Werner +49 170 333 93 53 Christiane Leithardt +49 179 104 80 64 A film by [email protected] MICHAEL HANEKE INTERNATIONAL SALES LES FILMS DU LOSANGE Agathe VALENTIN / Lise ZIPCI 22, Avenue Pierre 1er de Serbie - 75016 Paris Germany / Austria / France / Italy • 2H25 • Black & White • Format 1.85 [email protected] / Cell: +33 6 89 85 96 95 [email protected] / Cell: +33 6 75 13 05 75 in Cannes: Download of Photos & Press kit at: Booth F7 (Riviera) www.filmsdulosange.fr DP RB - anglais - VL 12/05/09 10:46 Page 4 A village in Protestant northern Germany. - 2 - - 3 - DP RB - anglais - VL 12/05/09 10:46 Page 6 1913-1914. On the eve of World War I. - 4 - - 5 - DP RB - anglais - VL 12/05/09 10:46 Page 8 The story of the children and teenagers of a church and school choir run by the village schoolteacher, and their families: the Baron, the steward, the pastor, the doctor, the midwife, the tenant farmers. - 6 - - 7 - DP RB - anglais - VL 12/05/09 10:46 Page 10 Strange accidents occur and gradually take on the character of a punishment ritual.