Birdsfoot Trefoil Lotus Corniculatus L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dorset Heath 2013 So Once Again You Have Me As Editor

NewsletterThe ofD theo Dorsetrset Flora H eGroupath 201 4 Chairman and VC9 Recorder Robin Walls; Secretary Laurence Taylor Editorial: John Newbould It would appear that the group had no complaints about the layout and content of the Dorset Heath 2013 so once again you have me as editor. The year was somewhat difficult for me as somehow, whenever I had to leave the room in Yorkshire Naturalists’ Union committee meetings in 2011, they managed to appoint me President for 2013 resulting in extra commitments in that county. During April 2013, Dorset hosted the National Forum for Biological Recording’s annual conference at the R.N.L.I. College at Poole. What a fabulous conference venue and the overnight accommodation was excellent. NFBR then joined Dorset naturalists with a joint meeting based at Studland helping to survey for the Cyril Diver project. Once again, duties took me away as I seem to be the conference administrator. The Flora Group had an interesting year, with variable numbers at field meetings. Never-the-less some important recording has been achieved including members engaging with recording bryophytes for the first time, one meeting to record fungi near Hardy’s Cottage, which thanks to the expertise of Bryan Edwards was very successful. We also had a few members try their hand at lichen recording In June 2014, I have been tasked by the Linnean Society to organise their annual field trip, which will be in June starting with a day on Portland and Chesil on the Saturday with Ballard Down and Studland on the Sunday. -

Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 9-17-2018 Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park" (2018). Botanical Studies. 85. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/85 This Flora of Northwest California-Checklists of Local Sites is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE REDWOOD NATIONAL & STATE PARKS James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State Univerity Arcata, California 14 September 2018 The Redwood National and State Parks are located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties in coastal northwestern California. The national park was F E R N S established in 1968. In 1994, a cooperative agreement with the California Department of Parks and Recreation added Del Norte Coast, Prairie Creek, Athyriaceae – Lady Fern Family and Jedediah Smith Redwoods state parks to form a single administrative Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosporum • northwestern lady fern unit. Together they comprise about 133,000 acres (540 km2), including 37 miles of coast line. Almost half of the remaining old growth redwood forests Blechnaceae – Deer Fern Family are protected in these four parks. -

Oregon City Nuisance Plant List

Nuisance Plant List City of Oregon City 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O. Box 3040, Oregon City, OR 97045 Phone: (503) 657-0891, Fax: (503) 657-7892 Scientific Name Common Name Acer platanoides Norway Maple Acroptilon repens Russian knapweed Aegopodium podagraria and variegated varieties Goutweed Agropyron repens Quack grass Ailanthus altissima Tree-of-heaven Alliaria officinalis Garlic Mustard Alopecuris pratensis Meadow foxtail Anthoxanthum odoratum Sweet vernalgrass Arctium minus Common burdock Arrhenatherum elatius Tall oatgrass Bambusa sp. Bamboo Betula pendula lacinata Cutleaf birch Brachypodium sylvaticum False brome Bromus diandrus Ripgut Bromus hordeaceus Soft brome Bromus inermis Smooth brome-grasses Bromus japonicus Japanese brome-grass Bromus sterilis Poverty grass Bromus tectorum Cheatgrass Buddleia davidii (except cultivars and varieties) Butterfly bush Callitriche stagnalis Pond water starwort Cardaria draba Hoary cress Carduus acanthoides Plumeless thistle Carduus nutans Musk thistle Carduus pycnocephalus Italian thistle Carduus tenufolius Slender flowered thistle Centaurea biebersteinii Spotted knapweed Centaurea diffusa Diffuse knapweed Centaurea jacea Brown knapweed Centaurea pratensis Meadow knapweed Chelidonium majou Lesser Celandine Chicorum intybus Chicory Chondrilla juncea Rush skeletonweed Cirsium arvense Canada Thistle Cirsium vulgare Common Thistle Clematis ligusticifolia Western Clematis Clematis vitalba Traveler’s Joy Conium maculatum Poison-hemlock Convolvulus arvensis Field Morning-glory 1 Nuisance Plant List -

Two Cryptic Species of Lotus (Fabaceae) from the Iberian Peninsula 21-45 Wulfenia 27 (2020): 21– 45 Mitteilungen Des Kärntner Botanikzentrums Klagenfurt

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Wulfenia Jahr/Year: 2020 Band/Volume: 27 Autor(en)/Author(s): Kramina Tatiana E., Samigullin Tahir H., Meschersky Ilya G. Artikel/Article: Two cryptic species of Lotus (Fabaceae) from the Iberian Peninsula 21-45 Wulfenia 27 (2020): 21– 45 Mitteilungen des Kärntner Botanikzentrums Klagenfurt Two cryptic species of Lotus (Fabaceae) from the Iberian Peninsula Tatiana E. Kramina, Tahir H. Samigullin & Ilya G. Meschersky Summary: The problem of cryptic species is well known in taxonomy of different groups of organisms, including plants, and their recognition can contribute to the assessment of global biodiversity and the development of conservation methods. Analyses of Lotus glareosus and related taxa from the Iberian Peninsula based on various types of data (i.e. sequences of nuclear ribosomal ITS-1-2, 5’ETS and cpDNA trnL-F, seven loci of nuclear microsatellites) revealed that the material earlier determined as ‘L. glareosus’ is subdivided into two genetically distant groups: L. carpetanus, related to L. conimbricensis, and L. glareosus, included in the L. corniculatus complex. Though only slight morphological distinctions were found between them, significant genetic differences comparable to those between sections of the genus Lotus (p-distance 0.07– 0.08 in ITS, 0.060 – 0.067 in ETS and 0.010 – 0.013 in trnL-F; substitution number 43 – 47 bp in ITS, 22–24 bp in ETS and 12–14 bp in trnL-F) and no evidence of genetic exchange suggest that these groups may represent two deeply diverged lineages that should be treated as two separate species. -

Phylogeny of the Genus Lotus (Leguminosae, Loteae): Evidence from Nrits Sequences and Morphology

813 Phylogeny of the genus Lotus (Leguminosae, Loteae): evidence from nrITS sequences and morphology G.V. Degtjareva, T.E. Kramina, D.D. Sokoloff, T.H. Samigullin, C.M. Valiejo-Roman, and A.S. Antonov Abstract: Lotus (120–130 species) is the largest genus of the tribe Loteae. The taxonomy of Lotus is complicated, and a comprehensive taxonomic revision of the genus is needed. We have conducted phylogenetic analyses of Lotus based on nrITS data alone and combined with data on 46 morphological characters. Eighty-one ingroup nrITS accessions represent- ing 71 Lotus species are studied; among them 47 accessions representing 40 species are new. Representatives of all other genera of the tribe Loteae are included in the outgroup (for three genera, nrITS sequences are published for the first time). Forty-two of 71 ingroup species were not included in previous morphological phylogenetic studies. The most important conclusions of the present study are (1) addition of morphological data to the nrITS matrix produces a better resolved phy- logeny of Lotus; (2) previous findings that Dorycnium and Tetragonolobus cannot be separated from Lotus at the generic level are well supported; (3) Lotus creticus should be placed in section Pedrosia rather than in section Lotea; (4) a broad treatment of section Ononidium is unnatural and the section should possibly not be recognized at all; (5) section Heineke- nia is paraphyletic; (6) section Lotus should include Lotus conimbricensis; then the section is monophyletic; (7) a basic chromosome number of x = 6 is an important synapomorphy for the expanded section Lotus; (8) the segregation of Lotus schimperi and allies into section Chamaelotus is well supported; (9) there is an apparent functional correlation be- tween stylodium and keel evolution in Lotus. -

Fruits and Seeds of Genera in the Subfamily Faboideae (Fabaceae)

Fruits and Seeds of United States Department of Genera in the Subfamily Agriculture Agricultural Faboideae (Fabaceae) Research Service Technical Bulletin Number 1890 Volume I December 2003 United States Department of Agriculture Fruits and Seeds of Agricultural Research Genera in the Subfamily Service Technical Bulletin Faboideae (Fabaceae) Number 1890 Volume I Joseph H. Kirkbride, Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L. Weitzman Fruits of A, Centrolobium paraense E.L.R. Tulasne. B, Laburnum anagyroides F.K. Medikus. C, Adesmia boronoides J.D. Hooker. D, Hippocrepis comosa, C. Linnaeus. E, Campylotropis macrocarpa (A.A. von Bunge) A. Rehder. F, Mucuna urens (C. Linnaeus) F.K. Medikus. G, Phaseolus polystachios (C. Linnaeus) N.L. Britton, E.E. Stern, & F. Poggenburg. H, Medicago orbicularis (C. Linnaeus) B. Bartalini. I, Riedeliella graciliflora H.A.T. Harms. J, Medicago arabica (C. Linnaeus) W. Hudson. Kirkbride is a research botanist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory, BARC West Room 304, Building 011A, Beltsville, MD, 20705-2350 (email = [email protected]). Gunn is a botanist (retired) from Brevard, NC (email = [email protected]). Weitzman is a botanist with the Smithsonian Institution, Department of Botany, Washington, DC. Abstract Kirkbride, Joseph H., Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L radicle junction, Crotalarieae, cuticle, Cytiseae, Weitzman. 2003. Fruits and seeds of genera in the subfamily Dalbergieae, Daleeae, dehiscence, DELTA, Desmodieae, Faboideae (Fabaceae). U. S. Department of Agriculture, Dipteryxeae, distribution, embryo, embryonic axis, en- Technical Bulletin No. 1890, 1,212 pp. docarp, endosperm, epicarp, epicotyl, Euchresteae, Fabeae, fracture line, follicle, funiculus, Galegeae, Genisteae, Technical identification of fruits and seeds of the economi- gynophore, halo, Hedysareae, hilar groove, hilar groove cally important legume plant family (Fabaceae or lips, hilum, Hypocalypteae, hypocotyl, indehiscent, Leguminosae) is often required of U.S. -

Evaluation of Sacred Lotus (Nelumbo Nucifera Gaertn.) As an Alternative Crop for Phyto-Remediation by Warner Steve Orozco Oband

Evaluation of Sacred Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn.) as an Alternative Crop for Phyto-remediation by Warner Steve Orozco Obando A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama May 6, 2012 Keywords: Aquaponics, Heavy Metals, Constructed Wetlands, CWs Copyright 2012 by Warner Orozco Obando Approved by Kenneth M. Tilt, Chair, Professor of Horticulture Floyd M. Woods, Co-chair, Associate Professor of Horticulture Fenny Dane, Professor of Horticulture J. Raymond Kessler, Professor of Horticulture Jeff L. Sibley, Professor of Horticulture Wheeler G. Foshee III, Associate Professor of Horticulture Abstract Lotus, Nelumbo nucifera, offers a wide diversity of uses as ornamental, edible and medicinal plant. An opportunity for growing lotus as a crop in Alabama also has the potential for phyto-remediation. Lotus was evaluated for remediation of trace elements focusing on manganese (Mn), organic compounds targeting s-metolachlor and filtering aquaculture waste water. Lotus was evaluated for filtering trace elements by establishing a base line for tissue composition and evaluating lotus capacity to grow in solutions with high levels of Mn (0, 5, 10, 15, or 50 mg/L). Increasing Mn concentrations in solution induced a linear increase in lotus Mn leaf concentrations. Hyper-accumulation of Al and Fe was detected in the rhizomes, while Na hyper-accumulated in the petioles, all without visible signs of toxicity. Mn treatments applied to lotus affected chlorophyll content. For example, chlorophyll a content increased linearly over time while chlorophyll b decreased. Radical scavenging activity (DPPH) did not change over time but correlated with total phenols content, showing a linear decrease after 6 weeks of treatment. -

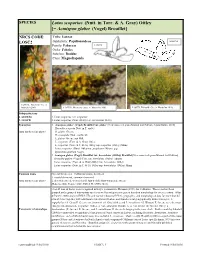

Lotus Scoparius (Nutt. in Torr. & A. Gray) Ottley [= Acmispon Glaber

SPECIES Lotus scoparius (Nutt. in Torr. & A. Gray) Ottley [= Acmispon glaber (Vogel) Brouillet] NRCS CODE: Tribe: Loteae LOSC2 Subfamily: Papilionoideae LOSCS2 Family: Fabaceae LOSCB Order: Fabales Subclass: Rosidae Class: Magnoliopsida LOSCB , Riverside Co., A. Montalvo 2009 LOSCS2, Monterey coast, A. Montalvo 2003 LOSCB, Riverside Co., A. Montalvo 2010, Subspecific taxa 1. LOSCS2 1. Lotus scoparius var. scoparius 2. LOSCB 2. Lotus scoparius (Nutt.) Ottley var. brevialatus Ottley Synonyms 1. Acmispon glaber (Vogel) Brouillet var. glaber [New name in Jepson Manual 2nd Edition, JepsonOnline 2010] Hosackia scoparia Nutt. in T. and G. (taxa numbered as above) H. glaber Greene H. crassifolia Nutt., not Benth L. glaber Greene, not Mill. L. scoparius (Torr. & A. Gray) Ottley L. scoparius (Nutt. in T. & G.) Ottley ssp. scoparius (Ottley) Munz Lotus scoparius (Nutt.) Ottley var. perplexans Hoover p.p. Syrmatium glabrum Vogel 2. Acmispon glaber (Vogel) Brouillet var. brevialatus (Ottley) Brouillet [New name in Jepson Manual 2nd Edition] Hosackia glabra (Vogel) Torr. var. brevialata (Ottley) Abrams Lotus scoparius (Torr. & A. Gray) Ottley var. brevialatus Ottley Lotus scoparius (Nutt. in T. & G.) Ottley ssp. brevialatus (Ottley) Munz Common name General for species: California broom, deerweed 1. coastal deerweed, common deerweed (taxa numbered as above) 2. desert deerweed, western bird's foot trefoil, short-winged deerweed (Roberts 2008, Painter 2009, USDA PLANTS 2010). Over 45 taxa of Lotus were recognized in Isely's treatment in Hickman (1993) for California. These taxa had been grouped and regrouped into various species as well as subgenera or genera based on morphology for over a century. Allan & Porter (2000) analyzed DNA (ITS and nuclear ribosomal DNA), geographic, and morphological data for more than 45 taxa of Lotus together with additional related taxa of Loteae and found several geographically distinct lineages. -

Forage and Habitat for Pollinators in the Northern Great Plains—Implications for U.S

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forage and Habitat for Pollinators in the Northern Great Plains—Implications for U.S. Department of Agriculture Conservation Programs Open-File Report 2020–1037 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey A B C D E F G H I Cover. A, Bumble bee (Bombus sp.) visiting a locowood flower. Photograph by Stacy Simanonok, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). B, Honey bee (Apis mellifera) foraging on yellow sweetclover (Melilotus officinalis). Photograph by Sarah Scott, USGS. C, Two researchers working on honey bee colonies in a North Dakota apiary. Photograph by Elyssa McCulloch, USGS. D, Purple prairie clover (Dalea purpurea) against a backdrop of grass. Photograph by Stacy Simanonok, USGS. E, Conservation Reserve Program pollinator habitat in bloom. Photograph by Clint Otto, USGS. F, Prairie onion (Allium stellatum) along the slope of a North Dakota hillside. Photograph by Mary Powley, USGS. G, A researcher assesses a honey bee colony in North Dakota. Photograph by Katie Lee, University of Minnesota. H, Honey bee foraging on alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Photograph by Savannah Adams, USGS. I, Bee resting on woolly paperflower (Psilostrophe tagetina). Photograph by Angela Begosh, Oklahoma State University. Front cover background and back cover, A USGS research transect on a North Dakota Conservation Reserve Program field in full bloom. Photograph by Mary Powley, USGS. Forage and Habitat for Pollinators in the Northern Great Plains—Implications for U.S. Department of Agriculture Conservation Programs By Clint R.V. Otto, Autumn Smart, Robert S. Cornman, Michael Simanonok, and Deborah D. Iwanowicz Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. -

Review: Medicago Truncatula As a Model for Understanding Plant Interactions with Other Organisms, Plant Development and Stress Biology: Past, Present and Future

CSIRO PUBLISHING www.publish.csiro.au/journals/fpb Functional Plant Biology, 2008, 35, 253-- 264 Review: Medicago truncatula as a model for understanding plant interactions with other organisms, plant development and stress biology: past, present and future Ray J. Rose Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Integrative Legume Research, School of Environmental and Life Sciences, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Medicago truncatula Gaertn. cv. Jemalong, a pasture species used in Australian agriculture, was first proposed as a model legumein 1990.Sincethat time M. truncatula,along withLotus japonicus(Regal) Larsen, hascontributed tomajor advances in understanding rhizobia Nod factor perception and the signalling pathway involved in nodule formation. Research using M. truncatula as a model has expanded beyond nodulation and the allied mycorrhizal research to investigate interactions with insect pests, plant pathogens and nematodes. In addition to biotic stresses the genetic mechanisms to ameliorate abiotic stresses such as salinity and drought are being investigated. Furthermore, M. truncatula is being used to increase understanding of plant development and cellular differentiation, with nodule differentiation providing a different perspective to organogenesis and meristem biology. This legume plant represents one of the major evolutionary success stories of plant adaptation to its environment, and it is particularly in understanding the capacity to integrate biotic and abiotic plant responses with plant growth and development that M. truncatula has an important role to play. The expanding genomic and genetic toolkit available with M. truncatula provides many opportunities for integrative biological research with a plant which is both a model for functional genomics and important in agricultural sustainability. -

On the Polymorphism of Cyanogenesis in Lotus Corniculatus L

Heredity (1983) 51 (3), 537—547 1983. The Genetical Society of Great Britain ONTHE POLYMORPHISM OF CYANOGENESIS IN LOTUS CORNICULATUS L. IX. SELECTIVE HERBIVORY IN NATURAL POPULATIONS AT PORTHDAFARCH, ANGLESEY S. G. COMPTON, S. G. BEESLEY AND DAVID A. JONES Unit of Genetics, University of Hull, Hull HU6 lAX Received1O.iii.83 SUMMARY The L. corniculatus populations at Porthdafarch are polymorphic for the charac- ters of leaf cyanogenesis, petal cyanogenesis and keel petal colour. Plants with cyanogenic leaves and petals occur less frequently on the sea cliffs than inland and previous studies have obtained circumstantial evidence of a link between the dine in leaf cyanogenesis and the distribution of selectively grazing molluscs. Counts of leaf and petal damage have confirmed that plants on the cliffs are grazed less heavily than those growing inland and have demonstrated that individuals with acyanogenic leaves or petals are liable to be chewed more heavily than their cyanogenic neighbours. Most of the damage was attributable to feeding by molluscs and it is concluded that herbivorous insects have only a minor role in the maintenance of the dines. 1. INTRODUCTION The population of Lotus corniculatus L. on the cliff along the S. W. facing coast of Porthdafarch, Holy Island, Anglesey contains a lower proportion of plants with cyanogenic leaves than two nearby populations less than 200 metres inland (Jones, 1962). Because this dine appeared to have been stable for several years and the two inland sites had essentially the same proportions of cyanogenic plants, in spite of being topographically very different, Ellis et a!., (1977) sought those environmental factors common to the inland sites by which they differed from the cliff site. -

Original Research Paper R Lavanya Pharmacy

VOLUME-7, ISSUE-4, APRIL-2018 • PRINT ISSN No 2277 - 8160 Original Research Paper Pharmacy LOTUS CORNICULATUS L.- A REVIEW Department of Pharmacy, Government Polytechnic for women, Nizamabad, R Lavanya Telangana, India. ABSTRACT : Lotus corniculatus L. (Fabaceae), commonly known as bird's foot trefoil, is a forage plant. It possesses cytotoxic, anti-inammatory, antibacterial and antifungal activity. The plant contains benzoic acid, transilin, isosalicin, soyasaponin I, dehydrosoyasaponin I, medicarpin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, pharbitoside A and p-coumaric acid. This review article provides information on the pharmacological activities of Lotus corniculatus L. KEYWORDS : Lotus corniculatus L, Bird's-foot, cytotoxic. INTRODUCTION Lotus corniculatus L. is a perennial legume, popular in temperate leaets obovate–elliptic, usually blunt. Stipules vestigial. climates for pasture, hay and silage production[1]. All the parts of the plant contain cyanogenic glycosides(hydrogen cyanide)[2]. In Fruit:Straight,narrow,round,brown,opening,spreadingpod small quantities, hydrogen cyanide has been shown to stimulate (legume). respiration and improve digestion, it is also claimed to be of benet in the treatment of cancer. In excess, however, it can cause respiratory failure and even death. The owers of some forms of the plant contain traces of prussic acid and so the plants can become mildly toxic when owering[3]. Bird's-foot-trefoil grows to between 5 and 35 cm (2 and 13.5 inches) high, and from June to September produces bright yolk-yellow pea- like blooms that are often patterned with streaks of red (hence the “bacon and eggs” reference in one of its many common names). The “birds-foot” in the plant's most common name refers to the claw- like arrangement of its black seed pods, while trefoil comes from the leaves, which at rst glance appear to consist of three separate Figure 1: Lotus corniculatusL.