Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ull History Centre: Papers of Alan Plater

Hull History Centre: Papers of Alan Plater U DPR Papers of Alan Plater 1936-2012 Accession number: 1999/16, 2004/23, 2013/07, 2013/08, 2015/13 Biographical Background: Alan Frederick Plater was born in Jarrow in April 1935, the son of Herbert and Isabella Plater. He grew up in the Hull area, and was educated at Pickering Road Junior School and Kingston High School, Hull. He then studied architecture at King's College, Newcastle upon Tyne, becoming an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1959 (since lapsed). He worked for a short time in the profession, before becoming a full-time writer in 1960. His subsequent career has been extremely wide-ranging and remarkably successful, both in terms of his own original work, and his adaptations of literary works. He has written extensively for radio, television, films and the theatre, and for the daily and weekly press, including The Guardian, Punch, Listener, and New Statesman. His writing credits exceed 250 in number, and include: - Theatre: 'A Smashing Day'; 'Close the Coalhouse Door'; 'Trinity Tales'; 'The Fosdyke Saga' - Film: 'The Virgin and the Gypsy'; 'It Shouldn't Happen to a Vet'; 'Priest of Love' - Television: 'Z Cars'; 'The Beiderbecke Affair'; 'Barchester Chronicles'; 'The Fortunes of War'; 'A Very British Coup'; and, 'Campion' - Radio: 'Ted's Cathedral'; 'Tolpuddle'; 'The Journal of Vasilije Bogdanovic' - Books: 'The Beiderbecke Trilogy'; 'Misterioso'; 'Doggin' Around' He received numerous awards, most notably the BAFTA Writer's Award in 1988. He was made an Honorary D.Litt. of the University of Hull in 1985, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1985. -

Angeli, Helen Rossetti, Collector Angeli-Dennis Collection Ca.1803-1964 4 M of Textual Records

Helen (Rossetti) Angeli - Imogene Dennis Collection An inventory of the papers of the Rossetti family including Christina G. Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Michael Rossetti, as well as other persons who had a literary or personal connection with the Rossetti family In The Library of the University of British Columbia Special Collections Division Prepared by : George Brandak, September 1975 Jenn Roberts, June 2001 GENEOLOGICAL cw_T__O- THE ROssFTTl FAMILY Gaetano Polidori Dr . John Charlotte Frances Eliza Gabriele Rossetti Polidori Mary Lavinia Gabriele Charles Dante Rossetti Christina G. William M . Rossetti Maria Francesca (Dante Gabriel Rossetti) Rossetti Rossetti (did not marry) (did not marry) tr Elizabeth Bissal Lucy Madox Brown - Father. - Ford Madox Brown) i Brother - Oliver Madox Brown) Olive (Agresti) Helen (Angeli) Mary Arthur O l., v o-. Imogene Dennis Edward Dennis Table of Contents Collection Description . 1 Series Descriptions . .2 William Michael Rossetti . 2 Diaries . ...5 Manuscripts . .6 Financial Records . .7 Subject Files . ..7 Letters . 9 Miscellany . .15 Printed Material . 1 6 Christina Rossetti . .2 Manuscripts . .16 Letters . 16 Financial Records . .17 Interviews . ..17 Memorabilia . .17 Printed Material . 1 7 Dante Gabriel Rossetti . 2 Manuscripts . .17 Letters . 17 Notes . 24 Subject Files . .24 Documents . 25 Printed Material . 25 Miscellany . 25 Maria Francesca Rossetti . .. 2 Manuscripts . ...25 Letters . ... 26 Documents . 26 Miscellany . .... .26 Frances Mary Lavinia Rossetti . 2 Diaries . .26 Manuscripts . .26 Letters . 26 Financial Records . ..27 Memorabilia . .. 27 Miscellany . .27 Rossetti, Lucy Madox (Brown) . .2 Letters . 27 Notes . 28 Documents . 28 Rossetti, Antonio . .. 2 Letters . .. 28 Rossetti, Isabella Pietrocola (Cole) . ... 3 Letters . ... 28 Rossetti, Mary . .. 3 Letters . .. 29 Agresti, Olivia (Rossetti) . -

Vol. VI, No. 4 (1945, Oct.)

THE SHAKESPEARE FELLOWSHIP JAN 29 1946 SEATTLE, WASH INC.TON The Shakespeare Fellowship was founded i,, London in 1922 under the presidency of Sir George Greenwo94~. VOL. VI OCTOBER, 194.5 NO. 4 Oxford-Shakespeare Case Loses Brilliant Advocate Bernard Mordaunt Ward (1893-1945), Author of The Seventeenth Earl oJ Oxjord Friends and admirers of Captain Bernard M. searching out the original records at great pains and Ward will be saddened to learn of his death, which expense. He took as his guiding principle in the occurred quite suddenly at his home, Lemsford Cot accomplishment of this task the following text of Itage, Lemsford, Hertfordshire, England, on October Edmund Lodge in Illustrations of Br,tish History 2, 1945. (17911: Captain Ward's untimely demise--due to over• "For genuine illustration of history, biography exertion in the war-removes the last of a distin• and manners, we must chiefly rely on ancient orig guished family of British soldier-scholars. He was inal papers. To them we must return for the correc• one of the founders of The Shakespeare Fellowship tion of past errors; for a supply of future materials; in 1922, and for several years prior to his return to and for proof of what hath already been delivered the British Army in 1940, served as Honorary Sec unto us." retary of The Ft-llowship. As author of The Seven• In order to keep the size of his book within reason• teentk Earl o/ Oxford, the authoritative biography able bounds, Captain Ward did not attempt to in o( Edward de Vere, based upon contemporary doc· troduce detailed Shakespearean arguments into The uments, and published by John Murray of London Seventeenth Earl of Oxford, being content to leave in 1928, Captain Ward will always occupy the place to others the rewarding task of making apparent the of honor next to the late J. -

2021 PDF Catalogue

Spring & Summer CATALOGUE2021 Contents 3 Spring & Summer Selection 4 Featured Title When I Think of My Body as a Horse by Wendy Pratt 6 Featured Title Talking to Stanley on the Telephone by Michael Schmidt 9 The PB Bookshelf The AQI by David Tait 10 The North 11 New Poets List Ugly Bird by Lauren Hollingsworth-Smith Have a nice weekend I think you’re interesting by Lucy Holt Aunty Uncle Poems by Gboyega Odubanjo Takeaway by Georgie Woodhead 14 Forthcoming Titles 15 Subject Codes Pamphlet | 9781912196418 | £6 Black Mascara (Waterproof) eBook | 9781912196517 | £4.50 Published 1st Feb 2021 Rosalind Easton 34pp Black Mascara (Waterproof) is a glamorous and lively debut exploring Rosalind Easton grew up in Salisbury and relationships, popular culture, and the enduring power of teenage memories. now lives in South East London, where she works as an English teacher. After a first degree at Exeter University, she trained as Full of wicked invention. – Imtiaz Dharker a dance teacher and spent several years Love and the possibilities of love and intimacy are examined and celebrated teaching tap, modern and ballet before completing her PGCE at Bristol and MA at and quotidian adventures like bra fittings and running mascara are given the Goldsmiths. She has recently completed her power of myth. – Ian McMillan PhD thesis on Sarah Waters. Black Mascara (Waterproof) is her first collection. Witty, sexy poems that strut across the page – Natalie Whittaker Pamphlet | 9781912196425 | £6 In Your Absence eBook | 9781912196524 | £4.50 Published 1st Feb 2021 Jill Penny 36pp In Your Absence is a response to a year of bereavement, a murder and a trial, Jill Penny is from a touring theatre and estrangements, departures and insights. -

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

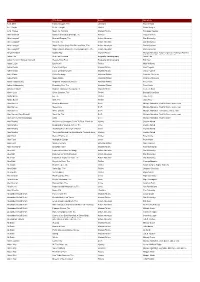

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. -

Layout 1 (Page 2)

ACTION THRILLER DRAMA KIDS COMEDY HORROR MARTIAL ARTS SPECIAL INTEREST DVD CATALOG TABLE OF CONTENTS FAMILY 3-4 ANIMATED 4-5 KID’S SOCCER 5 COMEDY 6 STAND-UP COMEDY 6 COMEDY TV DVD 7 DRAMA 8-11 TRUE STORIES COLLECTION 12-14 THRILLER 15-16 HORROR 16 ACTION 16 MARTIAL ARTS 17 EROTIC 17-18 DOCUMENTARY 18 MUSIC 18 NATURE 18-19 INFINITY ROYALS 20 INFINITY ARTHOUSE 20 INFINITY AUTHORS 21 DISPLAYS 22 TITLE INDEX 23-24 Josh Kirby: Trapped on Micro-Mini Kids Toyworld Now one inch tall, Josh Campbell has his Fairy Tale Police Department The lifelike toy creations of a fuddy-duddy work cut out, but being tiny has its perks. (FTPD) tinkerer rally to Josh's cause. Stars CORBIN Stars COLIN BAIN AND JOSH HAMMOND There’s trouble in Fairy Tale Land! For some reason, the ALLRED, JENNIFER BURNES AND DEREK 90 Minutes / Not Rated world’s best known fairy tales aren’t ending the way they WEBSTER Johnny Mysto Cat: DH9013 / UPC: 844628090131 should. So it’s up to the team at the Fairy Tale Police Department to put An enchanted ring transports a young 91 Minutes / Rated PG the Fairy Tales back on track, and assure they end they way they’re magician back to thrilling adventures in Cat: DH9081 / UPC: 844628090810 supposed to... Happily Ever After! Ancient Britain. Stars TORAN CAUDELL, FTPD: Case File 1 AMBER TAMBLYN AND PATRICK RENNA PINOCCHO, THE THREE LITTLE PIGS, 87 Minutes / Rated PG SNOW WHITE & THE SEVEN DWARFS, THE Cat: DH9008 / UPC: 844628090087 FROG PRINCE, SLEEPING BEAUTY 120 Minutes / Not Rated Cat: TE1069 / UPC: 844628010696 Josh Kirby: Human Pets Kids Of The Round Table Josh and his pals have timewarped to For Alex, Excalibur is just a legend, that is 70,379 and the Fatlings are holding them until he tumbles into a magic glade where hostage! Stars CORBIN ALLRED, JENNIFER the famed sword and Merlin the Magician BURNS AND DEREK WEBSTER appear. -

A Bibliography of the Walter Scott Publishing House

A Bibliography of the Walter Scott Publishing House by John R. Turner Department of Information and Library Studies University of Wales, Aberystwyth Contents Introduction 1 Bibliography Books and Pamphlets 8 Periodicals 413 Books in Series 414 Remainders 459 Agency 459 Titles Published but Not Seen 460 Titles Announced but Not Published 463 Index of Editors, Translators and Contributors 466 Index of Authors 469 Index of Titles 478 Introduction The following bibliography lists the total output of Walter Scott's publishing department. An attempt has been made to include all titles with a Walter Scott imprint in either separate publications, joint publications, or works published on behalf of some-one else (usually Vanity' publishing for the author). There were some significant moves in the company’s history which can be used to date publications. For example, the London publishing office moved from 14 Paternoster Square to 24 Warwick Lane, Paternoster Row, in July 1885 and moved again in October 1894 to 1 Paternoster Buildings (which appeared on title-page imprints as Paternoster Square). The firm became a limited company in 1892 changing its title to Walter Scott Limited, and finally changed its title to the Walter Scott Publishing Co Ltd in 1901. These and other changes are summarised in Table 1. The entries are arranged in chronological order by year and then alphabetically by author within each year. Anonymous works, along with anthologies and similar compilations without an obvious author, appear in the same alphabetical sequence under their titles. Each entry is given a number followed by a heading line consisting of the author's name (if known), the short title, and the date of publication: 635 ARNOLD, Matthew Strayed Reveller [1896] A large number of Scott’s books were issued without any indication of the date of publication. -

The Inventory of the Catherine Cookson Collection #483

The Inventory of the Catherine Cookson Collection #483 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center COOKSON, CATHERINE Purchase 1971 Manuscripts Box 1 1) THE BLIND MILLER. London, Macdonald & Company, 1963. a) Typescript, carbon typescript, and holograph, Ca. 350 pp. (#1). b) Dated November 12, 1962-January 23, 1963. Carbon typescript with holograph notation, 412 pp. (#2). · Box 2 2) COLOUR BLIND. London, Macdonald & Company, 1953. Typescript with holograph corrections, 258 pp. (#3). 3) THE DEVIL AND MARY ANN. London, Macdonald & Company, 1958. a) Dated January 15, 1957. Holograph, Ca. 100 pp. (#4). b) Typescript with holograph corrections, Ca. 300 pp. (#5). Box 3 4) FANNY McBRIDE (Original title: THE LADIES). a) Holograph, Ca. 75 pp. (#6)~ b) Typescript with holograph corrections, Ca. 300 pp. (#6). c) Carbon typescript with holograph corrections, 333 pp. (#7). Box 4 5) FENWICK HOUSES, London, Macdonald & Company, 1960. (Original title: CHRISTINE). Typescript and holograph, Ca. 350 pp. (#8). 6) THE FIFTEEN STREETS. London, Macdonald & Company, 1952. a) Holograph, 350 pp. (#9). b) Typescript with holograph corrections, 300 pp. (#10). Box 5 7) THE GARMENT, London, Macdonald & Company, 1962. a) Typescript, carbon typescript, and holograph, Ca. 350 pp. (#11). b) Titled THE DEEDS OF MERCY, dated November 5, 1959. Typescript, carbon typescript, and holograph, Ca. 300 pp. (#12). c) Titled THE DEEDS OF MERCY. Typescript, carbon typescript, and holograph, Ca, 300 pp. (#13). ' - ' p~e2 COOKSON, CATHERINE Purchase 1971 Box 6 d) Typescript with holograph corrections, Ca. 375 pp. (#14). e) Typescript with holograph corrections and printer's marks, Ca. 375 pp. (#15). Box 7 8) THE GLASS VIRGIN. -

The Word, National Centre for the Written Word South Shields Awards and Publications

The Word, National Centre for the Written Word South Shields Awards and Publications The building has achieved the following accolades: 2016 — Living North Awards Best Regeneration or Restoration Project — Mixology Best Public Sector Interiors Project of the Year — Concrete Society Awards National Finalist 2017 — RICS Awards Project of the Year Community Beneit Award Tourism and Leisure Award Design Through Innovation Award — RIBA Awards Project of the Year Regional Award — LABC Awards Best Public Service Building Award The building will be submitted for the following awards: 2017 — Constructing Excellence Awards — British Construction Industry Awards — RTPI Awards — Civic Trust Award The building has appeared in the following publications: — RIBA Journal “Mind your language” April 2017 — International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA) - “1001 Libraries to see before you die” 3rd February 2017 — ARCHITECT - The Journal of the American Institute of Architects “The Word - FaulknerBrowns Architect” 17th January 2017 — ArchDaily “The Word - National Centre for the Written Word / FaulknerBrowns Architects” 9th January 2017 — ImmoWeek “Le choix Immoweek : « The Word », un nouvel écrin pour la littérature” 10th January 2017 — Designing Libraries “The Word - design thinking for our time” 20th October 2016 — Living North “The Word : National Centre for the Written Word” October 2016 — Chronicle Live “‘It’s absolutely brilliant’ - what writer David Baddiel said about new South Shields cultural hub” 19th October 2016 The Word, National Centre for the Written Word 3 The Word, National Centre for the Written Word 5 Foreword This document celebrates the completion of The Word, National Centre for the Written Word in South Shields. It describes the ambition of South Tyneside Council and it’s partner Muse Developments and illustrates the collaborative design approach which enabled the successful delivery of the building. -

Descendants of Anthony Watson

Descendants of Anthony Watson Charles E. G. Pease Pennyghael Isle of Mull Descendants of Anthony Watson 1-Anthony Watson Anthony married someone. He had one son: Joshua. 2-Joshua Watson, son of Anthony Watson, was born on 10 Sep 1672 in Huntwell, Northumberland and died on 14 Jun 1757 at age 84. Joshua married Ann Rutter on 16 Dec 1697 in Rounton, Yorkshire. Ann was born on 19 Feb 1679 in Busby, Yorkshire and died on 14 Nov 1726 at age 47. They had seven children: Mary, Sarah, Hugh, Robert, Phebe, Deborah, and Joseph. 3-Mary Watson1,2 was born in 1700 in Huntwell, Northumberland. Mary married Appleby Bowron,1,2 son of Caleb Bowron2 and Anne Raine, on 17 Apr 1725 in Cotherstone, Barnard Castle, County Durham. Appleby was born on 18 Mar 1700 in Cotherstone, Barnard Castle, County Durham. They had four children: Joshua, Caleb, Mary, and Elizabeth. Noted events in his life were: • He had a residence in Cotherstone, Barnard Castle, County Durham. • He worked as a Husbandman in Cotherstone, Barnard Castle, County Durham. 4-Joshua Bowron was born in 1726. Joshua married Frances Gallilee. They had one daughter: Hannah. 5-Hannah Bowron was born in 1753 in Darlington, County Durham and died in 1836 at age 83. Hannah married John Coates, son of Kay Coates and Ann, on 5 Nov 1776 in Staindrop, County Durham. John was born on 6 Jul 1759 and died in 1843 at age 84. They had ten children: Elizabeth, Mary, Hannah, Hannah, Frances, Bathsheba, William, Caleb, Joshua, and John. 6-Elizabeth Coates 6-Mary Coates 6-Hannah Coates 6-Hannah Coates 6-Frances Coates3 was born in 1782 in Darlington, County Durham and died on 29 Mar 1867 in Darlington, County Durham at age 85. -

Barbarian Masquerade a Reading of the Poetry of Tony Harrison And

1 Barbarian Masquerade A Reading of the Poetry of Tony Harrison and Simon Armitage Christian James Taylor Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of English August 2015 2 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation fro m the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement The right of Christian James Taylor to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2015 The University of Leeds and Christian James Taylor 3 Acknowledgements The author hereby acknowledges the support and guidance of Dr Fiona Becket and Professor John Whale, without whose candour, humour and patience this thesis would not have been possible. This thesis is d edicat ed to my wife, Emma Louise, and to my child ren, James Byron and Amy Sophia . Additional thanks for a lifetime of love and encouragement go to my mother, Muriel – ‘ never indifferent ’. 4 Abstract This thesis investigates Simon Armitage ’ s claim that his poetry inherits from Tony Harrison ’ s work an interest in the politics o f form and language, and argues that both poets , although rarely compared, produce work which is conceptually and ideologically interrelated : principally by their adoption of a n ‘ un - poetic ’ , deli berately antagonistic language which is used to invade historically validated and culturally prestigious lyric forms as part of a critique of canons of taste and normative concepts of poetic register which I call barbarian masquerade . -

A History of the Walter Scott Publishing House

A History of the Walter Scott Publishing House by John R. Turner A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of Economic and Social Studies for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Information and Library Studies University of Wales, Aberystwyth 1995 Abstract Sir Walter Scott of Newcastle upon Tyne was bom in poverty and died a millionaire in 1910. He has been almost totally neglected by historians. He owned a publishing company which made significant contributions to cultural life and which has also been almost completely ignored. The thesis gives an account of Scott's life and his publishing business. Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 : The Life of Sir Walter Scott 4 Chapter 2: Walter Scott's Start as a Publisher 25 Chapter 3: Reprints, the Back-Bone of the Business 45 Chapter 4: Editors and Series 62 Chapter 5: Progressive Ideas 112 Chapter 6: Overseas Trade 155 Chapter 7: Final Years 177 Chapter 8: Book Production 209 Chapter 9: Financial Management and Performance of the Company 227 Conclusion 260 Bibliography 271 Appendices List of contracts, known at present, undertaken by Walter Scott, or Walter Scott and Middleton 1 Printing firms employed to produce Scott titles 7 Transcriptions of surviving company accounts 11 Walter Scott, aged 73, from Newcastle Weekly Chronicle, 2nd December 1899, p 7. Introduction The most remarkable fact concerning Walter Scott is his almost complete neglect by historians since his death in 1910. He created a vast business organization based on building and contracting which included work for the major railway companies, the first London underground railway, the construction of docks and reservoirs, ship building, steel manufacture and coal mining.