Public Education and Intelligent Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Intelligent Design Creationist Movement: Its True Nature and Goals

UNDERSTANDING THE INTELLIGENT DESIGN CREATIONIST MOVEMENT: ITS TRUE NATURE AND GOALS A POSITION PAPER FROM THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY OFFICE OF PUBLIC POLICY AUTHOR: BARBARA FORREST, Ph.D. Reviewing Committee: Paul Kurtz, Ph.D.; Austin Dacey, Ph.D.; Stuart D. Jordan, Ph.D.; Ronald A. Lindsay, J. D., Ph.D.; John Shook, Ph.D.; Toni Van Pelt DATED: MAY 2007 ( AMENDED JULY 2007) Copyright © 2007 Center for Inquiry, Inc. Permission is granted for this material to be shared for noncommercial, educational purposes, provided that this notice appears on the reproduced materials, the full authoritative version is retained, and copies are not altered. To disseminate otherwise or to republish requires written permission from the Center for Inquiry, Inc. Table of Contents Section I. Introduction: What is at stake in the dispute over intelligent design?.................. 1 Section II. What is the intelligent design creationist movement? ........................................ 2 Section III. The historical and legal background of intelligent design creationism ................ 6 Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) ............................................................................ 6 McLean v. Arkansas (1982) .............................................................................. 6 Edwards v. Aguillard (1987) ............................................................................. 7 Section IV. The ID movement’s aims and strategy .............................................................. 9 The “Wedge Strategy” ..................................................................................... -

Argumentation and Fallacies in Creationist Writings Against Evolutionary Theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1

Nieminen and Mustonen Evolution: Education and Outreach 2014, 7:11 http://www.evolution-outreach.com/content/7/1/11 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Argumentation and fallacies in creationist writings against evolutionary theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1 Abstract Background: The creationist–evolutionist conflict is perhaps the most significant example of a debate about a well-supported scientific theory not readily accepted by the public. Methods: We analyzed creationist texts according to type (young earth creationism, old earth creationism or intelligent design) and context (with or without discussion of “scientific” data). Results: The analysis revealed numerous fallacies including the direct ad hominem—portraying evolutionists as racists, unreliable or gullible—and the indirect ad hominem, where evolutionists are accused of breaking the rules of debate that they themselves have dictated. Poisoning the well fallacy stated that evolutionists would not consider supernatural explanations in any situation due to their pre-existing refusal of theism. Appeals to consequences and guilt by association linked evolutionary theory to atrocities, and slippery slopes to abortion, euthanasia and genocide. False dilemmas, hasty generalizations and straw man fallacies were also common. The prevalence of these fallacies was equal in young earth creationism and intelligent design/old earth creationism. The direct and indirect ad hominem were also prevalent in pro-evolutionary texts. Conclusions: While the fallacious arguments are irrelevant when discussing evolutionary theory from the scientific point of view, they can be effective for the reception of creationist claims, especially if the audience has biases. Thus, the recognition of these fallacies and their dismissal as irrelevant should be accompanied by attempts to avoid counter-fallacies and by the recognition of the context, in which the fallacies are presented. -

Ono Mato Pee 145

789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 148215 9 789493 148215 789493 9 9 789493 148215 9 148215 789493 148215 789493 9 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 148215 789493 9 789493 148215 9 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 99 789493789493 148215148215 9 789493 148215 99 789493789493 148215148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 145 PEE MATO ONO Graphic Design Systems, and the Systems of Graphic Design Francisco Laranjo Bibliography M.; Drenttel, W. & Heller, S. (2012) Within graphic design, the concept of systems is profoundly Escobar, A. (2018) Designs for Looking Closer 4: Critical Writings rooted in form. When a term such as system is invoked, it is the Pluriverse (New Ecologies for on Graphic Design. Allworth Press, normally related to macro and micro-typography, involving pp. 199–207. the Twenty-First Century). Duke book design and typesetting, but also addressing type design University Press. Manzini, E. (2015) Design, When or parametric typefaces. Branding and signage are two other Jenner, K. (2016) Chill Kendall Jenner Everybody Designs: An Introduction Didn’t Think People Would Care to Design for Social Innovation. domains which nearly claim exclusivity of the use of the That She Deleted Her Instagram. Massachusetts: MIT Press. word ‘systems’ in relation to graphic design. A key example of In: Vogue. Available at: https://www. Meadows, D. (2008) Thinking in this is the influential bookGrid Systems in Graphic Design vogue.com/article/kendall-jenner- Systems. -

Answers to Practice Quiz #2

Philosophy 1104: Critical Thinking Answers to Practice Quiz #2 [Total: 50 marks] 1. In which of the following pairs of propositions does A provide conclusive evidence for B? Also say whether or not A provides at least some evidence, no matter how weak (i.e. say whether A is positively relevant to B). Write just „Yes‟ or „No‟ in each column provided. A B Conclusive Some evidence? evidence? (i) Fred just hit a hole-in-one Fred is a very good golfer No Yes (ii) I have between 4 and 6 eggs I have at least 3 eggs Yes (iii) I have at least 4 eggs I have 5 or more eggs No Yes (iv) It‟s not the case that every Every politician is honest No Yes politician is corrupt. (v) Janet likes listening to Jazz Vancouver is west of Calgary No No (vi) Simpson is a world-class skier Simpson is a non-smoker No Yes (vii) We‟re having fish for supper We‟re having trout for supper No Yes (viii) Qin‟s theory is rejected by all Qin‟s theory is false No Yes relevant scientific authorities (ix) Sally is a Catholic Sally has eight children No Yes (x) Ali stabbed a man in Vernon, Ali first entered Canada in No No B.C. in 1998. 2002. [1 mark each] In rows where you say ‘yes’ in the first column, you should of course say ‘yes’ in the second as well! Or just leave the second column blank, if you prefer. 2. Each of the following definitions is flawed in some way (each in just one way, I think, or at least one main one). -

Toward an Extended Evolutionary Synthesis 10-13 July 2008

18th Altenberg Workshop in Theoretical Biology 2008 Toward an Extended Evolutionary Synthesis 10-13 July 2008 organized by Massimo Pigliucci and Gerd B. Müller Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognition Research Altenberg, Austria The topic More than 60 years have passed since the conceptual integration of several strands of evolutionary theory into what has come to be called the Modern Synthesis. Despite major advances since, in all methodological and disciplinary domains of biology, the Modern Synthesis framework has remained surprisingly static and is still regarded as the standard theoretical paradigm of evolutionary biology. But for some time now there have been calls for an expansion of the Synthesis framework through the integration of more recent achievements in evolutionary theory. The challenge for the present workshop is clear: How do we make sense, conceptually, of the astounding advances in biology since the 1940s, when the Modern Synthesis was taking shape? Not only have we witnessed the molecular revolution, from the discovery of the structure of DNA to the genomic era, we are also grappling with the increasing feeling – as reflected, for example, by the proliferation of “-omics” (proteomics, metabolomics, “interactomics,” and even “phenomics”) – that we just don't have the theoretical and analytical tools necessary to make sense of the bewildering diversity and complexity of living organisms. By contrast, in organismal biology, a number of new approaches have opened up new theoretical horizons, with new possibilities -

On the Interaction of Function, Constraint and Complexity in Evolutionary Systems

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF PHYSICAL SCIENCES AND ENGINEERING ELECTRONICS AND COMPUTER SCIENCE Volume 1 of 1 On The Interaction Of Function, Constraint And Complexity In Evolutionary Systems by Adam Paul Davies Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2014 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF PHYSICAL SCIENCES AND ENGINEERING Electronics and Computer Science Doctor of Philosophy ON THE INTERACTION OF FUNCTION, CONSTRAINT AND COMPLEXITY IN EVOLUTIONARY SYSTEMS by Adam Paul Davies Biological evolution contains a general trend of increasing complexity of the most complex organisms. But artificial evolution experiments based on the mechanisms described in the current theory generally fail to reproduce this trend; instead, they commonly show systematic trends of complexity minimisation. In this dissertation we seek evolutionary mechanisms that can explain these apparently conflicting observations. To achieve this we use a reverse engineering approach by building computational simulations of evolution. One highlighted problem is that even if complexity is beneficial, evolutionary simulations struggle with apparent roadblocks that prevent them from scaling to complexity. Another is that even without roadblocks, it is not clear what drives evolution to become more complex at all. With respect to the former, a key roadblock is how to evolve ‘irreducibly complex’ or ‘non- decomposable’ functions. Evidence from biological evolution suggests a common way to achieve this is by combining existing functions – termed ‘tinkering’ or ‘building block evolution’. But in simulation this approach generally fails to scale across multiple levels of organisation in a recursive manner. We provide a model that identifies the problem hindering recursive evolution as increasing ‘burden’ in the form of ‘internal selection’ as joined functions become more complex. -

Mike Kelley's Studio

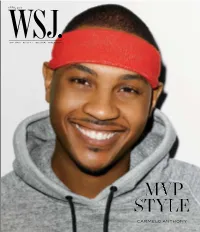

No PMS Flood Varnish Spine: 3/16” (.1875”) 0413_WSJ_Cover_02.indd 1 2/4/13 1:31 PM Reine de Naples Collection in every woman is a queen BREGUET BOUTIQUES – NEW YORK FIFTH AVENUE 646 692-6469 – NEW YORK MADISON AVENUE 212 288-4014 BEVERLY HILLS 310 860-9911 – BAL HARBOUR 305 866-1061 – LAS VEGAS 702 733-7435 – TOLL FREE 877-891-1272 – WWW.BREGUET.COM QUEEN1-WSJ_501x292.indd 1-2 01.02.13 16:56 BREGUET_205640303.indd 2 2/1/13 1:05 PM BREGUET_205640303.indd 3 2/1/13 1:06 PM a sporting life! 1-800-441-4488 Hermes.com 03_501,6x292,1_WSJMag_Avril_US.indd 1 04/02/13 16:00 FOR PRIVATE APPOINTMENTS AND MADE TO MEASURE INQUIRIES: 888.475.7674 R ALPHLAUREN.COM NEW YORK BEVERLY HILLS DALLAS CHICAGO PALM BEACH BAL HARBOUR WASHINGTON, DC BOSTON 1.855.44.ZEGNA | Shop at zegna.com Passion for Details Available at Macy’s and macys.com the new intense fragrance visit Armanibeauty.com SHIONS INC. Phone +1 212 940 0600 FA BOSS 0510/S HUGO BOSS shop online hugoboss.com www.omegawatches.com We imagined an 18K red gold diving scale so perfectly bonded with a ceramic watch bezel that it would be absolutely smooth to the touch. And then we created it. The result is as aesthetically pleasing as it is innovative. You would expect nothing less from OMEGA. Discover more about Ceragold technology on www.omegawatches.com/ceragold New York · London · Paris · Zurich · Geneva · Munich · Rome · Moscow · Beijing · Shanghai · Hong Kong · Tokyo · Singapore 26 Editor’s LEttEr 28 MasthEad 30 Contributors 32 on thE CovEr slam dunk Fashion is another way Carmelo Anthony is scoring this season. -

Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It?

Leaven Volume 17 Issue 2 Theology and Science Article 6 1-1-2009 Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It? Chris Doran [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Doran, Chris (2009) "Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It?," Leaven: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven/vol17/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Leaven by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Doran: Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It? Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It? CHRIS DORAN imaginethatwe have all had occasion to look up into the sky on a clear night, gaze at the countless stars, and think about how small we are in comparison to the enormity of the universe. For everyone except Ithe most strident atheist (although I suspect that even s/he has at one point considered the same feeling), staring into space can be a stark reminder that the universe is much grander than we could ever imagine, which may cause us to contemplate who or what might have put this universe together. For believers, looking up at tJotestars often puts us into the same spirit of worship that must have filled the psalmist when he wrote, "The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands" (Psalms 19.1). -

Intelligent Design Is Not Science” Given by John G

An Outline of a lecture entitled, “Intelligent Design is not Science” given by John G. Wise in the Spring Semester of 2007: Slide 1 Why… … do humans have so much trouble with wisdom teeth? … is childbirth so dangerous and painful? Because a big, thinking brain is an advantage, and evolution is imperfect. Slide 2 Charles Darwin’s Revolutionary Idea His book changed the world. All life forms on this planet are related to each other through “Descent with modification over generations from a common ancestor”. Natural processes fully explain the biological connections between all life on the planet. Slide 3 Darwin’s Idea is Dangerous (from the book of the same title by Daniel Dennett) If we have evolution, we no longer need a Creator to create each and every species. Darwinism is dangerous because it infers that God did not directly and purposefully create us. It simply states that we evolved. Slide 4 Intelligent Design Attempts to Counter Darwin “Intelligent Design” has been proposed as way out of this dilemma. – Phillip Johnson, William Dembski, and Michael Behe (to name a few). They attempt to redefine science to encompass the supernatural as well as the natural world. They accept Darwin’s evolution, if an Intelligent Designer is (sometimes) substituted for natural selection. Design arguments are not new: − 1250 - St. Thomas Aquinas - first design argument − 1802 - Natural Theology - William Paley – perhaps the best(?) design argument Slide 5 What is Science? A specific way of understanding the natural world. Based on the idea that our senses give us accurate information about the Universe. -

Book Review: Jerry A. Coyne's Why Evolution Is True

A peer-reviewed electronic journal published by the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies ISSN 1541-0099 20(1) – June 2009 Book review: Jerry A. Coyne’s Why Evolution Is True Russell Blackford, Monash University Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Evolution and Technology Journal of Evolution and Technology - Vol. 20 Issue 1 – June 2009 - pgs 61-66 http://jetpress.org/v20/blackford.htm Why Evolution Is True. By Jerry A. Coyne. Viking, New York, 2009. 282 pp., $27.95 (hardback). ISBN: 978 0 670 02053 9 (all page references to this edition) Jerry A. Coyne is a professor at the University of Chicago, where his research focuses on evolutionary genetics and speciation. In Why Evolution Is True, he presents a full-scale defence of modern evolutionary theory, which can, so he notes, be described in one long sentence: Life on earth evolved gradually beginning with one primitive species – perhaps a self-replicating molecule – that lived more than 3.5 billion years ago; it then branched out over time, throwing off many new and diverse species; and the mechanism for most (but not all) of evolutionary change is natural selection. (3.) This breaks down into six components: the fact of evolution, in the sense of genetic change over time; the idea of gradualism, of changes taking place over many generations (although sometimes they come about relatively quickly, depending on the evolutionary pressures operating); the phenomenon of speciation, whereby new species split off from existing lineages; the common ancestry of different species, since new species, -

Clearing the Highest Hurdle: Human-Based Case Studies Broaden Students’ Knowledge of Core Evolutionary Concepts

The Journal of Effective Teaching an online journal devoted to teaching excellence Clearing the highest hurdle: Human-based case studies broaden students’ knowledge of core evolutionary concepts Alexander J. Werth1 Hampden-Sydney College, Hampden-Sydney, VA 23943 Abstract An anonymous survey instrument was used for a ten year study to gauge college student attitudes toward evolution. Results indicate that students are most likely to accept evolu- tion as a historical process for change in physical features of non-human organisms. They are less likely to accept evolution as an ongoing process that shapes all traits (including biochemical, physiological, and behavioral) in humans. Students who fail to accept the factual nature of human evolution do not gain an accurate view of evolution, let alone modern biology. Fortunately, because of students’ natural curiosity about their bodies and related topics (e.g., medicine, vestigial features, human prehistory), a pedagogical focus on human evolution provides a fun and effective way to teach core evolutionary concepts, as quantified by the survey. Results of the study are presented along with useful case studies involving human evolution. Keywords: Survey, pedagogy, biology, evolution, Darwin. All science educators face pedagogical difficulties, but when considering the social rami- fications of scientific ideas, few face as great a challenge as biology teachers. Studies consistently show more than half of Americans reject any concept of biological evolution (Harris Poll, 2005, Miller et al., 2006). Students embody just such a cross-section of soci- ety. Much ink has been spilled explaining how best to teach evolution, particularly to unwilling students (Cavallo and McCall, 2008, Nelson, 2008). -

Evolution Is a Short-Order Cook, Not a Watchmaker

NATURE|Vol 435|19 May 2005 CORRESPONDENCE When science meets religion in the classroom SIR – In the Editorial “Dealing with design” such a reconciliation impossible because faith scientific challenges to their faith should seek (Nature434,1053; 2005), Natureclaims that and science are two mutually exclusive ways guidance from a theologian, not a scientist. scientists have not dealt effectively with the of looking at the world. For such scientists, Scientists should never have to apologize for threat to evolutionary biology posed by Natureapparently prescribes hypocrisy. The teaching science. ‘intelligent design’ (ID) creationism. Rather real business of science teachers is to teach Jerry Coyne than ignoring, dismissing or attacking ID, science, not to help students shore up world- Department of Ecology and Evolution, University scientists should, the editors suggest, learn views that crumble when they learn science. of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637, USA how religious people can come to terms And ID creationism is not science, despite Peter AtkinsLincoln College, University of Oxford with science, and teach these methods of the editors’ suggestion that ID “tries to use Colin BlakemoreMedical Research Council, London accommodation in the classroom. The goal scientific methods to find evidence of God in Richard DawkinsOxford University Museum, University of Oxford of science education should thus be “to point nature”. Rather, advocates of ID pretend to use Steve JonesGalton Laboratories, University College London to options other than ID for reconciling scientific methods to support their religious Richard LewontinMuseum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University science and belief ”. In this way, students’ faith preconceptions. It has no more place in the John Maddox 9 Pitt Street, London W8 4NX will not be challenged by scientific truth, and biology classroom than geocentrism has in Paul NurseThe Rockefeller University, New York evolution will triumph.