Landed Property and Elite Conflict in Ottoman Tulkarm End of the Crusades, This Area Was Poorly Inhabited for Security Reasons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor. -

A Study of Muslim Economic Thinking in the 11Th A.H

Munich Personal RePEc Archive A study of Muslim economic thinking in the 11th A.H. / 17th C.E. century Islahi, Abdul Azim Islamic Economics Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75431/ MPRA Paper No. 75431, posted 06 Dec 2016 02:55 UTC Abdul Azim Islahi Islamic Economics Research Center King Abdulaziz University Scientific Publising Centre King Abdulaziz University P.O. Box 80200, Jeddah, 21589 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia FOREWORD There are numerous works on the history of Islamic economic thought. But almost all researches come to an end in 9th AH/15th CE century. We hardly find a reference to the economic ideas of Muslim scholars who lived in the 16th or 17th century, in works dealing with the history of Islamic economic thought. The period after the 9th/15th century remained largely unexplored. Dr. Islahi has ventured to investigate the periods after the 9th/15th century. He has already completed a study on Muslim economic thinking and institutions in the 10th/16th century (2009). In the mean time, he carried out the study on Muslim economic thinking during the 11th/17th century, which is now in your hand. As the author would like to note, it is only a sketch of the economic ideas in the period under study and a research initiative. It covers the sources available in Arabic, with a focus on the heartland of Islam. There is a need to explore Muslim economic ideas in works written in Persian, Turkish and other languages, as the importance of these languages increased in later periods. -

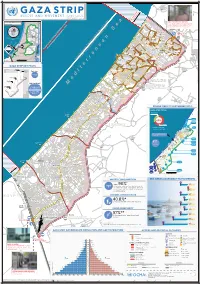

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Download the PDF File

This study focuses on the role of the Mirage in the Sands: Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa, the Ottoman Special Organization (SO), in the Sinai-Palestine The Ottoman Special front during the First World War. The Organization on the SO was defined by its use of various tactics of unconventional warfare, namely Sinai-Palestine Front intelligence-gathering, espionage, guerilla Polat Safi warfare, and propaganda. Along the Sinai- Palestine front, the operational goal to which these tactics were put to use was to bring about an uprising in British-occupied Egypt.1 The SO hoped to secure the support of the tribal and Bedouin populations of Sinai-Palestine front and the people of Egypt and encourage them to rise up against the British rule.2 The SO’s involvement on the Sinai- Palestine front was part of a broader effort developed between Germany and the Ottoman State for the purposes of encircling Egypt. An examination of the SO’s work in Palestine will illuminate the nature of the peripheral strategy the Germans and Ottomans employed outside of Europe during World War I and how it was applied in practice. As part of this broader strategy, in Palestine the SO engaged in a volunteer recruitment campaign, worked to foment rebellion behind enemy lines, engaged in guerilla warfare, and carried out intelligence duties. By examining the nature and contours of the SO’s operations there, this study aims to provide both new insights into the regional aspects of a crucial organization and also valuable information which will offer a firmer ground for future comparative studies on the different operational bases of the SO. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87598-1 - The War for Palestine: Rewriting the History of 1948, Second Edition Edited by Eugene L. Rogan and Avi Shlaim Excerpt More information Introduction The Palestine War lasted less than twenty months, from the United Nations resolution recommending the partition of Palestine in November 1947 to the final armistice agreement signed between Israel and Syria in July 1949. Those twenty months transformed the political landscape of the Middle East forever. Indeed, 1948 may be taken as a defining moment for the region as a whole. Arab Palestine was destroyed and the new state of Israel established. Egypt, Syria and Lebanon suffered outright defeat, Iraq held its lines, and Transjordan won at best a pyrrhic victory. Arab public opinion, unprepared for defeat, let alone a defeat of this magnitude, lost faith in its politicians. Within three years of the end of the Palestine War, the prime ministers of Egypt and Lebanon and the king of Jordan had been assassinated, and the president of Syria and the king of Egypt over- thrown by military coups. No event has marked Arab politics in the second half of the twentieth century more profoundly. The Arab–Israeli wars, the Cold War in the Middle East, the rise of the Palestinian armed struggle, and the politics of peace-making in all of their complexity are a direct con- sequence of the Palestine War. The significance of the Palestine War also lies in the fact that it was the first challenge to face the newly independent states of the Middle East. -

National Report, State of Palestine United Nations

National Report, State of Palestine United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat III) 2014 Ministry of Public Works and Housing National Report, State of Palestine, UN-Habitat 1 Photo: Jersualem, Old City Photo for Jerusalem, old city Table of Contents FORWARD 5 I. INTRODUCTION 7 II. URBAN AGENDA SECTORS 12 1. Urban Demographic 12 1.1 Current Status 12 1.2 Achievements 18 1.3 Challenges 20 1.4 Future Priorities 21 2. Land and Urban Planning 22 2. 1 Current Status 22 2.2 Achievements 22 2.3 Challenges 26 2.4 Future Priorities 28 3. Environment and Urbanization 28 3. 1 Current Status 28 3.2 Achievements 30 3.3 Challenges 31 3.4 Future Priorities 32 4. Urban Governance and Legislation 33 4. 1 Current Status 33 4.2 Achievements 34 4.3 Challenges 35 4.4 Future Priorities 36 5. Urban Economy 36 5. 1 Current Status 36 5.2 Achievements 38 5.3 Challenges 38 5.4 Future Priorities 39 6. Housing and Basic Services 40 6. 1 Current Status 40 6.2 Achievements 43 6.3 Challenges 46 6.4 Future Priorities 49 III. MAIN INDICATORS 51 Refrences 52 Committee Members 54 2 Lists of Figures Figure 1: Percent of Palestinian Population by Locality Type in Palestine 12 Figure 2: Palestinian Population by Governorate in the Gaza Strip (1997, 2007, 2014) 13 Figure 3: Palestinian Population by Governorate in the West Bank (1997, 2007, 2014) 13 Figure 4: Palestinian Population Density of Built-up Area (Person Per km²), 2007 15 Figure 5: Percent of Change in Palestinian Population by Locality Type West Bank (1997, 2014) 15 Figure 6: Population Distribution -

Anglo-French Relations in Syria: from Entente Cordiale to Sykes-Picot a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the College of Arts A

Anglo-French Relations in Syria: From Entente Cordiale to Sykes-Picot A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts James L. Bowman May 2020 © 2020 James L. Bowman. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Anglo-French Relations in Syria: From Entente Cordiale to Sykes-Picot by JAMES L. BOWMAN has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Peter John Brobst Associate Professor of History Florenz Plassmann Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract BOWMAN, JAMES L., M.A., May 2020, History Anglo-French Relations in Syria: From Entente Cordiale to Sykes-Picot Director of Thesis: Peter John Brobst Though the Entente Cordiale of 8 April, 1904 addressed several outstanding imperial tensions between the British Empire and the French Third Republic, other imperial disputes remained unresolved in the lead-up to World War I. This thesis explores Anglo-French tensions in Ottoman Syria, from the signing of the Entente to the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1916. Syria proved to be a cause of frictions that brought many buried Anglo-French resentments back to the surface and created new ones. Cultural, strategic, and economic interests were at stake, interests which weighed heavily upon the Entente powers and which could not easily be forgone for the sake of ‘cordiality’. This thesis presents evidence that unresolved Anglo-French tensions in Syria raised serious concerns among officials of both empires as to the larger future of their Entente, and that even after the Entente joined in war against their common enemies, such doubts persisted. -

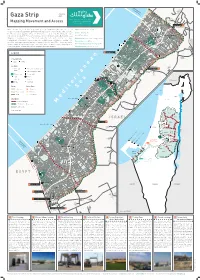

Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary

Zikim Karmiya No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles Yad Mordekhai January Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary Ar-Rasheed Wastewater Treatment Lagoons Sources: OCHA, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics of Statistics Bureau Central OCHA, Palestinian Sources: Erez Crossing 1 Al-Qarya Beit Hanoun Al-Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) Erez What is known today as the Gaza Strip, originally a region in Mandatory Palestine, was created Width 5.7-12.5 km / 3.5 – 7.7 mi through the armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt in 1949. From that time until 1967, North Gaza Length ~40 km / 24.8 mi Al- Karama As-Sekka the Strip was under Egyptian control, cut off from Israel as well as the West Bank, which was Izbat Beit Hanoun al-Jaker Road Area 365 km2 / 141 m2 Beit Hanoun under Jordanian rule. In 1967, the connection was renewed when both the West Bank and the Gaza Madinat Beit Lahia Al-'Awda Strip were occupied by Israel. The 1993 Oslo Accords define Gaza and the West Bank as a single Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Population 1,943,398 • 48% Under age 17 July 2019 Industrial Zone Ash-Shati Housing Project Jabalia Sderot territorial unit within which freedom of movement would be permitted. However, starting in the camp al-Wazeer Unemployment rate 47% 2019 Q2 Jabalia Camp Khalil early 90s, Israel began a gradual process of closing off the Strip; since 2007, it has enforced a full Ash-Sheikh closure, forbidding exit and entry except in rare cases. Israel continues to control many aspects of Percentage of population receiving aid 80% An-Naser Radwan Salah Ad-Deen 2 life in Gaza, most of its land crossings, its territorial waters and airspace. -

1948 Arab‒Israeli

1948 Arab–Israeli War 1 1948 Arab–Israeli War מלחמת or מלחמת העצמאות :The 1948 Arab–Israeli War, known to Israelis as the War of Independence (Hebrew ,מלחמת השחרור :, Milkhemet Ha'atzma'ut or Milkhemet HA'sikhror) or War of Liberation (Hebrewהשחרור Milkhemet Hashikhrur) – was the first in a series of wars fought between the State of Israel and its Arab neighbours in the continuing Arab-Israeli conflict. The war commenced upon the termination of the British Mandate of Palestine and the Israeli declaration of independence on 15 May 1948, following a period of civil war in 1947–1948. The fighting took place mostly on the former territory of the British Mandate and for a short time also in the Sinai Peninsula and southern Lebanon.[1] ., al-Nakba) occurred amidst this warﺍﻟﻨﻜﺒﺔ :Much of what Arabs refer to as The Catastrophe (Arabic The war concluded with the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Background Following World War II, on May 14, 1948, the British Mandate of Palestine came to an end. The surrounding Arab nations were also emerging from colonial rule. Transjordan, under the Hashemite ruler Abdullah I, gained independence from Britain in 1946 and was called Jordan, but it remained under heavy British influence. Egypt, while nominally independent, signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 that included provisions by which Britain would maintain a garrison of troops on the Suez Canal. From 1945 on, Egypt attempted to renegotiate the terms of this treaty, which was viewed as a humiliating vestige of colonialism. Lebanon became an independent state in 1943, but French troops would not withdraw until 1946, the same year that Syria won its independence from France. -

Chapter 5. Development Frameworks

Chapter 5 JERICHO Regional Development Study Development Frameworks CHAPTER 5. DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORKS 5.1 Socioeconomic Framework Socioeconomic frameworks for the Jericho regional development plan are first discussed in terms of population, employment, and then gross domestic product (GDP) in the region. 5.1.1 Population and Employment The population of the West Bank and Gaza totals 3.76 million in 2005, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) estimation.1 Of this total, the West Bank has 2.37 million residents (see the table below). Population growth of the West Bank and Gaza between 1997 and 2005 was 3.3%, while that of the West Bank was slightly lower. In the Jordan Rift Valley area, including refugee camps, there are 88,912 residents; 42,268 in the Jericho governorate and 46,644 in the Tubas district2. Population growth in the Jordan Rift Valley area is 3.7%, which is higher than that of the West Bank and Gaza. Table 5.1.1 Population Trends (1997-2005) (Unit: number) Locality 1997 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 CAGR West Bank and Gaza 2,895,683 3,275,389 3,394,046 3,514,868 3,637,529 3,762,005 3.3% West Bank 1,873,476 2,087,259 2,157,674 2,228,759 2,300,293 2,372,216 3.0% Jericho governorate 31,412 37,066 38,968 40,894 40,909 42,268 3.8% Tubas District 35,176 41,067 43,110 45,187 45,168 46,644 3.6% Study Area 66,588 78,133 82,078 86,081 86,077 88,912 3.7% Study Area (Excl. -

Letters from Vidin: a Study of Ottoman Governmentality and Politics of Local Administration, 1864-1877

LETTERS FROM VIDIN: A STUDY OF OTTOMAN GOVERNMENTALITY AND POLITICS OF LOCAL ADMINISTRATION, 1864-1877 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Mehmet Safa Saracoglu ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Carter Vaughn Findley, Adviser Professor Jane Hathaway ______________________ Professor Kenneth Andrien Adviser History Graduate Program Copyright by Mehmet Safa Saracoglu 2007 ABSTRACT This dissertation focuses on the local administrative practices in Vidin County during 1860s and 1870s. Vidin County, as defined by the Ottoman Provincial Regulation of 1864, is the area that includes the districts of Vidin (the administrative center), ‛Adliye (modern-day Kula), Belgradcık (Belogradchik), Berkofça (Bergovitsa), İvraca (Vratsa), Rahova (Rahovo), and Lom (Lom), all of which are located in modern-day Bulgaria. My focus is mostly on the post-1864 period primarily due to the document utilized for this dissertation: the copy registers of the county administrative council in Vidin. Doing a close reading of these copy registers together with other primary and secondary sources this dissertation analyzes the politics of local administration in Vidin as a case study to understand the Ottoman governmentality in the second half of the nineteenth century. The main thesis of this study contends that the local inhabitants of Vidin effectively used the institutional framework of local administration ii in this period of transformation in order to devise strategies that served their interests. This work distances itself from an understanding of the nineteenth-century local politics as polarized between a dominating local government trying to impose unprecedented reforms designed at the imperial center on the one hand, and an oppressed but nevertheless resistant people, rebelling against the insensitive policies of the state on the other. -

Resources for the Study of Islamic Architecture Historical Section

RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION Prepared by: Sabri Jarrar András Riedlmayer Jeffrey B. Spurr © 1994 AGA KHAN PROGRAM FOR ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION BIBLIOGRAPHIC COMPONENT Historical Section, Bibliographic Component Reference Books BASIC REFERENCE TOOLS FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE This list covers bibliographies, periodical indexes and other basic research tools; also included is a selection of monographs and surveys of architecture, with an emphasis on recent and well-illustrated works published after 1980. For an annotated guide to the most important such works published prior to that date, see Terry Allen, Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography. Cambridge, Mass., 1979 (available in photocopy from the Aga Khan Program at Harvard). For more comprehensive listings, see Creswell's Bibliography and its supplements, as well as the following subject bibliographies. GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHIES AND PERIODICAL INDEXES Creswell, K. A. C. A Bibliography of the Architecture, Arts, and Crafts of Islam to 1st Jan. 1960 Cairo, 1961; reprt. 1978. /the largest and most comprehensive compilation of books and articles on all aspects of Islamic art and architecture (except numismatics- for titles on Islamic coins and medals see: L.A. Mayer, Bibliography of Moslem Numismatics and the periodical Numismatic Literature). Intelligently organized; incl. detailed annotations, e.g. listing buildings and objects illustrated in each of the works cited. Supplements: [1st]: 1961-1972 (Cairo, 1973); [2nd]: 1972-1980, with omissions from previous years (Cairo, 1984)./ Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography, ed. Terry Allen. Cambridge, Mass., 1979. /a selective and intelligently organized general overview of the literature to that date, with detailed and often critical annotations./ Index Islamicus 1665-1905, ed.