Oral Tradition 3.1-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orality in Writing: Its Cultural and Political Function in Anglophone African, African-Caribbean, and African-Canadian Poetry

ORALITY IN WRITING: ITS CULTURAL AND POLITICAL FUNCTION IN ANGLOPHONE AFRICAN, AFRICAN-CARIBBEAN, AND AFRICAN-CANADIAN POETRY A Thesis submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Yaw Adu-Gyamfi Spring 1999 © Copyright Yaw Adu-Gyamfi, 1999. All rights reserved. National Ubrary Bib!iotheque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1 A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Vol", ,eferet1C8 Our file Not,e ,life,encs The author has granted a non L' auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format electronique. The author retains ownership of the L' auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permISSlOn. autorisation. 0-612-37868-3 Canada UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN College of Graduate Studies and Research SUMMARY OF DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Yaw Adu-Gyamfi Department of English Spring 1999 -EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Dr. -

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This Page Intentionally Left Blank Shadows in the Field

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This page intentionally left blank Shadows in the Field New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology Second Edition Edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley 1 2008 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright # 2008 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shadows in the field : new perspectives for fieldwork in ethnomusicology / edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-532495-2; 978-0-19-532496-9 (pbk.) 1. Ethnomusicology—Fieldwork. I. Barz, Gregory F., 1960– II. Cooley, Timothy J., 1962– ML3799.S5 2008 780.89—dc22 2008023530 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper bruno nettl Foreword Fieldworker’s Progress Shadows in the Field, in its first edition a varied collection of interesting, insightful essays about fieldwork, has now been significantly expanded and revised, becoming the first comprehensive book about fieldwork in ethnomusicology. -

The Challenge of Oral Epic to Homeric Scholarship

humanities Article The Challenge of Oral Epic to Homeric Scholarship Minna Skafte Jensen The Saxo Institute, Copenhagen University, Karen Blixens Plads 8, DK-2300 Copenhagen S, Denmark; [email protected] or [email protected] Received: 16 November 2017; Accepted: 5 December 2017; Published: 9 December 2017 Abstract: The epic is an intriguing genre, claiming its place in both oral and written systems. Ever since the beginning of folklore studies epic has been in the centre of interest, and monumental attempts at describing its characteristics have been made, in which oral literature was understood mainly as a primitive stage leading up to written literature. With the appearance in 1960 of A. B. Lord’s The Singer of Tales and the introduction of the oral-formulaic theory, the paradigm changed towards considering oral literature a special form of verbal art with its own rules. Fieldworkers have been eagerly studying oral epics all over the world. The growth of material caused that the problems of defining the genre also grew. However, after more than half a century of intensive implementation of the theory an internationally valid sociological model of oral epic is by now established and must be respected in cognate fields such as Homeric scholarship. Here the theory is both a help for readers to guard themselves against anachronistic interpretations and a necessary tool for constructing a social-historic context for the Iliad and the Odyssey. As an example, the hypothesis of a gradual crystallization of these two epics is discussed and rejected. Keywords: epic; genre discussion; oral-formulaic theory; fieldwork; comparative models; Homer 1. -

Musicology Today Journal of the National University of Music Bucharest

Musicology Today Journal of the National University of Music Bucharest Issue 3 (39) July-September 2019 Title: Laudatio for Professor Philip V. Bohlman Author: Costin Moisil E-mail: Source: Musicology Today: Journal of the National University of Music Bucharest / Volume 10 / Issue 3 (39) / July-September 2019, pp 219-224 Link to this article: musicologytoday.ro/39/MT39laudationesBohlman Moisil.pdf How to cite this article: Costin Moisil, “Laudatio for Professor Philip V. Bohlman”, Musicology Today: Journal of the National University of Music Bucharest, 10/3 (39) (2019), 219-224. Published by: Editura Universității Naționale de Muzică București Musicology Today: Journal of the National University of Music Bucharest is indexed by EBSCO, RILM, and ERIH PLUS Laudatio Laudatio for Professor Philip V. Bohlman Festive Meeting of the National University of Music Senate. Bucharest, November 22nd, 2019 t is a great honour and gladness for our university to grant today the title of doctor honoris causa to Philip Vilas Bohlman, the Ludwig Rosenberger IDistinguished Service Professor in Jewish History, Music and the Humanities in the Department of Music at the University of Chicago. As you have already noticed on the event poster, Professor Bohlman is an ethnomusicologist. Among the 45 musicians to whom the title of doctor honoris causa has been granted by the Bucharest National University of Music there are only eight musicologists. Professor Philip Bohlman is the second ethnomusicologist who receives the title after Professor Jean-Jacques Nattiez who is rather appreciated as musical semiotician. The granting of this title to an ethnomusicologist represents a great happiness for the Department of Musicology, whose member I am and whose founder there was another eth- nomusicologist, Constantin Brăiloiu. -

Illinois Classical Studies

NOTICE: Return or renew all Library Materialsl The Minimum Fee for each Lost Book Is $50.00. The person charging this material is responsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for discipli- nary action and may result In dismissal from the University. To renew call Telephone Center, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN e-f ^.ft.f r OCT [im L161—O-1096 A ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XVIII 1993 ISSN 0363-1923 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XVIII 1993 SCHOLARS PRESS ISSN 0363-1923 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XVIII Studies in Honor of Miroslav Marcovich ©1993 The Board of Trustees University of Illinois Copies of the journal may be ordered from: Scholars Press Membership Services P.O. Box 15399 Atlanta, GA 30333-0399 Printed in the U.S.A. 220 :^[r EDITOR David Sansone ADVISORY EDITORIAL COMMITTEE John J. Bateman Howard Jacobson Gerald M. Browne S. Douglas Olson William M. Calder III Maryline G. Parca CAMERA-READY COPY PRODUCED BY Britt Johnson, under the direction of Mary Ellen Fryer Illinois Classical Studies is published annually by Scholars Press. Camera- ready copy is edited and produced in the Department of the Classics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Each conu-ibutor receives twenty-five offprints. Contributions should be addressed to: The Editor, Illinois Classical Studies Department of the Classics 4072 Foreign Languages Building 707 South Mathews Avenue Urbana, Illinois 61801 ^-AUro s ioM --J^ojrco ^/c/ — PREFACE The Department of the Classics of the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign and the Advisory Editorial Committee of Illinois Classical Studies are pleased to devote this issue and the next to the publication of Studies in Honor of Miroslav Marcovich. -

Comparative Research on Oral Traditions: a Memorial for Milman Parry

160 BOOK REVIEWS James W . Heisig Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture Nagoya, Japan Foley, John M iles, editor. Comparative Research on Oral Traditions: A Memorial for Milman Parry. Columbus, Ohio: Slavica Publishers, 1987. 597 pages. Hardcover US$29.95. ISBN 0-89357-173-3. As every folklorist knows, the co-founders of the modern study of oral poetry are the classicist M ilman Parry and his student, the slavicist Albert Lord. Lord has had his festschrift: Oral Traditional Literature: A Festschrift for Albert Bates Lord, ed. John Miles Foley (1981). The prolific editor of that work has also given us the standard bibliography_ Oral-Formulaic Theory and Research: An Introduction and Annotated Bibliography (1984)_as well as a welcome history~The Theory of Oral Composition: History and Methodology (1988)— of the Parry-Lord theory and its in fluence. Now Foley has produced a memorial festschrift for Parry, who died in 1935. The work starts off with a preface by Albert Lord, a pleasantly anecdotal re flection on Parry’s life and influence. It is followed by the editor’s somewhat con fusing introduction. According to Foley, “ Parry’s activity in the field . • initiated the comparative method in oral literature research ” (18). Foley goes on to say that “ Africa, with its plethora of tongues and traditions, is beginning to yield startling new information about oral tradition and culture, while some of the most ancient civi lization of the world, among them the Indie, Sumerian, and Hittite, also show signs of oral transmission of tales,” and he concludes these thoughts with the assertion that “ [t]his enormous field of research and scholarship, still in its relative infancy, is ul timately the bequest of M ilm an Parry ” (19). -

Bibliography

Colby Quarterly Volume 29 Issue 3 September Article 13 September 1993 Bibliography Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 29, no.3, September 1993 This Back Matter is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. et al.: Bibliography Bibliography Thefollowing areworks referredtointhepapersofthis volume. Thepublicationdates listed in the bibliography are those submitted by the contributors. ADKINS, A. W. H. 1960. Merit and Responsibility. Oxford. ---.1969. ''Threatening, Abusing and Feeling Angry in the Homeric Poems." JHS 89: 7-21. ALExIOU, M. 1974. The Ritual Lament in Greek Tradition. Cambridge, Eng. ALLEN, T.W. 1924. Homer: The Origins and the Transmission. Oxford. ALLEN, W. 1939. "The Theme of the Suitors in the Odyssey." TAPA 70: 14-24. ALTER, R. 1989. The Pleasures ofReading in an Ideological Age. New York. APTHORP, M. 1980. "The Obstacles to Telemachus' Return." CQ 30: 1-22. AREND, W. 1933. Die typische Szenen bei Homer. Berlin. ARRIGHETTI, G. 1991. "Eoikota tekna goneusi: etica eroica e continuita genealogica nell'epos greco." SIFC 9: 133-47. ARTHUR, M. 1981. "The Divided World: Iliad VI." In Reflections o/Women in Antiquity, ed. H. P. Foley, 19-43. New York. AUSTIN, N. 1975. Archery at the Dark ofthe Moon. Berkeley. Ax, W. 1932. "Die Parodos des Oidipus Tyrannos." Hermes 67: 413-37. BASSETT, S.E. 1938. The Poetry ofHomer. Berkeley. BASSO, E. 1985. A Musical View ofthe Universe. Philadelphia. BECK, W., 1991. -

Where Now the Harp? Listening for the Sounds of Old English Verse, from Beowulf to the Twentieth Century

Oral Tradition, 24/2 (2009): 485-502 Where Now the Harp? Listening for the Sounds of Old English Verse, from Beowulf to the Twentieth Century Chris Jones nis þær hearpan sweg, / gomen in geardum, swylce ðær iu wæron (2458b-59)1 There is no sound of the harp, delight in courts, as there once were The way to learn the music of verse is to listen to it. (Pound 1951:56) Even within an advanced print culture, poetry arguably never escapes the oral dimension. For Ezra Pound, whose highly intertextual epic The Cantos, so conscious of its page appearance, could only be the product of such a print culture, poetry was nevertheless “an art of pure sound,” the future of which in English was to be the “orchestration” of different European systems of sound-patterning (Pound 1973:33). Verbal orchestration is meaningless without auditors; it goes without saying that the notion of oral literature simultaneously implies the concept of aural literature. This much is also evident from the very beginning of Beowulf: Hwæt, we Gar-Dena in geardagum, / þeodcyninga þrym gefrunon . (“Listen, we have heard of the Spear-Danes in times past, of the glory of the people’s kings . ,” lines 1-2). While the conventionality of the opening might suggest the evocation of a formulaic idiom often associated with oral composition,2 the emphasis is clearly on aurality, on hearing a voice. Much work has been done in recent decades on the evidence in Old English written texts for a poetics that draws on compositional methods derived from an oral culture, either as it had survived into a period of widespread literacy, or as it was imagined to have once existed.3 This essay will not directly address that valuable rehabilitation of oral-formulaic theory into a more sophisticated understanding of early medieval scribal culture, although it will draw on it at times. -

Compound Diction and Traditional Style in Beowulf and Genesis A

Oral Tradition, 6/1 (1991): 79-92 Compound Diction and Traditional Style in Beowulf and Genesis A Jeffrey Alan Mazo One of the most striking features of Anglo-Saxon alliterative poetry is the extraordinary richness of the vocabulary. Many words appear only in poetry; almost every poem contains words, usually nominal or adjectival compounds, which occur nowhere else in the extant literature. Creativity in coining new compounds reaches its apex in the 3182-line heroic epic Beowulf. In his infl uential work The Art of Beowulf, Arthur G. Brodeur sets out the most widely accepted view of the diction of that poem (1959:28): First, the proportion of such compounds in Beowulf is very much higher than that in any other extant poem; and, secondly, the number and the richness of the compounds found in Beowulf and nowhere else is astonishingly large. It seems reasonable, therefore, to regard the many unique compounds in Beowulf, fi nely formed and aptly used, as formed on traditional patterns but not themselves part of a traditional vocabulary. And to say that they are formed on traditional patterns means only that the character of the language spoken by the poet and his hearers, and the traditional tendency towards poetic idealization, determined their character and form. Their elevation, and their harmony with the poet’s thought and feeling, refl ect that tendency, directed and controlled by the genius of a great poet. It goes without saying that the poet of Beowulf was no “unwashed illiterate,” but a highly trained literary artist who could transcend the traditional medium. -

Oral Tradition

_____________________________________________________________ Volume 6 January 1991 Number 1 _____________________________________________________________ Editor Editorial Assistants John Miles Foley Sarah J. Feeny David Henderson Managing Editor Whitney Strait Lee Edgar Tyler J. Chris Womack Book Review Editor Adam Brooke Davis Slavica Publishers, Inc. Slavica Publishers, Inc. For a complete catalog of books from Slavica, with prices and ordering information, write to: Slavica Publishers, Inc. P.O. Box 14388 Columbus, Ohio 43214 ISSN: 0883-5365 Each contribution copyright (c) 1991 by its author. All rights reserved. The editor and the publisher assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion by the authors. Oral Tradition seeks to provide a comparative and interdisciplinary focus for studies in oral literature and related fields by publishing research and scholarship on the creation, transmission, and interpretation of all forms of oral traditional expression. As well as essays treating certifiably oral traditions, OT presents investigations of the relationships between oral and written traditions, as well as brief accounts of important fieldwork, a Symposium section (in which scholars may reply at some length to prior essays), review articles, occasional transcriptions and translations of oral texts, a digest of work in progress, and a regular column for notices of conferences and other matters of interest. In addition, occasional issues will include an ongoing annotated bibliography of relevant research and the annual Albert Lord and Milman Parry Lectures on Oral Tradition. OT welcomes contributions on all oral literatures, on all literatures directly influenced by oral traditions, and on non-literary oral traditions. Submissions must follow the list-of reference format (style sheet available on request) and must be accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope for return or for mailing of proofs; all quotations of primary materials must be made in the original language(s) with following English translations. -

Hero As Citizen Models of Heroic Thought and Action in Homer, Plato and Rousseau

Man as Hero - Hero as Citizen Models of Heroic Thought and Action in Homer, Plato and Rousseau Dominic Stefanson Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Politics School of History and Politics The University of Adelaide December 2004 Frontisp iece Illustration included in print copy of thesis: Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Socrates (1787) iii Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………… v Declaration…………………………………………………………………….. vi Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………. vii Introduction…………………………………………………………………… 1 PART I HOMER: THE BIRTH OF HEROISM 1. Homeric Man: The Hero …………………………………………………… 21 • Homeric heroes as models for men 22 • Seeking immortal glory achieving a “god-like status” 26 • Who is the hero? Preconditions for heroism 35 • A guide to heroism: transparency of thought, speech and action 44 • The transparency of Homeric narration 48 • Conclusion 55 2. Homeric Polis: the absence of a polis……………………………………… 57 • Finley and Adkins 58 • Seeking a polis in the Iliad 66 • The heroic code as an anti-model 77 • Patroclus’ funeral games as a microcosm of the polis 87 • Conclusion 93 PART II PLATO: EXTENDING HEROISM TO THE POLITICAL 3. Platonic Man: The philosopher as a new hero…………………………… 95 • Socrates: an heroic life 97 • Socratic Intellectualism: the primacy of knowledge 101 • Androgynous virtue 106 • Seeking eternity: philosophy as an activity for gods 111 • Tripartite psychology: heroism within human reach 117 • Theory of Forms 119 • The late dialogues 125 • Conclusion 130 iv 4. Platonic Polis: The political engagement of the heroic philosopher…….. 133 • Enlisting Philosophers to rule 135 • The elitist nature of philosophical rule throughout the Platonic corpus 137 • Philosophical leadership in the late dialogues 143 • The benefits of philosophical rule: harmony and unity in the Republic 150 • Does the community benefit from philosophical leadership? 154 • Conclusion 162 PART III ROUSSEAU: THE DEMISE OF HEROISM IN POLITICAL THOUGHT 5. -

Cr2016-Program.Pdf

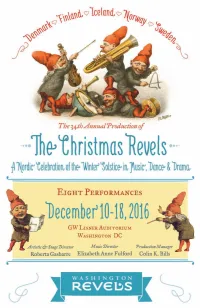

l Artistic Director’s Note l Welcome to one of our warmest and most popular Christmas Revels, celebrating traditional material from the five Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. We cannot wait to introduce you to our little secretive tomtenisse; to the rollicking and intri- cate traditional dances, the exquisitely mesmerizing hardingfele, nyckelharpa, and kantele; to Ilmatar, heaven’s daughter; to wild Louhi, staunch old Väinämöinen, and dashing Ilmarinen. This “journey to the Northlands” beautifully expresses the beating heart of a folk community gathering to share its music, story, dance, and tradition in the deep midwinter darkness. It is interesting that a Christmas Revels can feel both familiar and entirely fresh. Washing- ton Revels has created the Nordic-themed show twice before. The 1996 version was the first show I had the pleasure to direct. It was truly a “folk” show, featuring a community of people from the Northlands meeting together in an annual celebration. In 2005, using much of the same script and material, we married the epic elements of the story with the beauty and mystery of the natural world. The stealing of the sun and moon by witch queen Louhi became a rich metaphor for the waning of the year and our hope for the return of warmth and light. To create this newest telling of our Nordic story, especially in this season when we deeply need the circle of community to bolster us in the darkness, we come back to the town square at a crossroads where families meet at the holiday to sing the old songs, tell the old stories, and step the circling dances to the intricate stringed fiddles.