Information for Parents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crafting Alliances

05-Wei-45241.qxd 2/14/2007 5:16 PM Page 191 CHAPTER 5 Crafting Alliances egardless of how successful a social enterprise is at mobilizing funds, most R organizations will inevitably face resource and capacity constraints as a limiting factor to achieving their mission. The resources that any single organi- zation brings to bear on a social problem are often dwarfed by the magnitude and complexity of most social problems. Thus, social entrepreneurs often pursue alliance approaches as a means to mobilizing resources, financial and nonfinan- cial, from the larger context and beyond their own organizational boundaries, to achieve increased mission impact. Social enterprise alliances among nonprofits, nonprofits and business, nonprofits and government, and even across all sectors in the form of tripartite alliances between nonprofit, government, and business have become increasingly common in recent years. Because alliances capitalize on the resources and capacities of more than one organization and capture syn- ergies that would otherwise often go unrealized, they have the potential to gen- erate mission impact far beyond what the individual contributors could achieve independently. This chapter first describes some alliance trends in the social sec- tor and illustrates them with case examples. Next, we introduce a conceptual framework that can be helpful for developing an alliance strategy. Finally, we briefly introduce the chapter’s two case studies, which offer readers an opportu- nity for in-depth analysis of a range of alliance approaches. ALLIANCE TRENDS Increased Competition Increased competition due to a growing number of nonprofits coupled with recent overall declines in social sector funding have contributed to a dramatic 191 05-Wei-45241.qxd 2/14/2007 5:16 PM Page 192 192 Entrepreneurship in the Social Sector increase in the number and form of social enterprise alliances. -

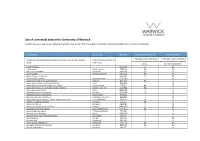

Use of Contextual Data at the University of Warwick Please Use

Use of contextual data at the University of Warwick Please use the table below to check whether your school meets the eligibility criteria for a contextual offer. For more information about our contextual offer please visit our website or contact the Undergraduate Admissions Team. School Name School Postcode School Performance Free School Meals 'Y' indicates a school which meets the 'Y' indicates a school which meets the Free School Meal criteria. Schools are listed in alphabetical order. school performance citeria. 'N/A' indicates a school for which the data is not available. 6th Form at Swakeleys UB10 0EJ N Y Abbey College, Ramsey PE26 1DG Y N Abbey Court Community Special School ME2 3SP N Y Abbey Grange Church of England Academy LS16 5EA Y N Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College ST2 8LG Y Y Abbey Hill School and Technology College, Stockton TS19 8BU Y Y Abbey School, Faversham ME13 8RZ Y Y Abbeyfield School, Northampton NN4 8BU Y Y Abbeywood Community School BS34 8SF Y N Abbot Beyne School and Arts College, Burton Upon Trent DE15 0JL Y Y Abbot's Lea School, Liverpool L25 6EE Y Y Abbotsfield School UB10 0EX Y N Abbotsfield School, Uxbridge UB10 0EX Y N School Name School Postcode School Performance Free School Meals Abbs Cross School and Arts College RM12 4YQ Y N Abbs Cross School, Hornchurch RM12 4YB Y N Abingdon And Witney College OX14 1GG Y NA Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX Y Y Abraham Guest Academy WN5 0DQ Y Y Abraham Moss High School, Manchester M8 5UF Y Y Academy 360 SR4 9BA Y Y Accrington Academy BB5 4FF Y Y Acklam Grange -

A Practical Guide for Disabled People

HB6 A Practical Guide for Disabled People Where to find information, services and equipment Foreword We are pleased to introduce the latest edition of A Practical Guide for Disabled People. This guide is designed to provide you with accurate up-to-date information about your rights and the services you can use if you are a disabled person or you care for a disabled relative or friend. It should also be helpful to those working in services for disabled people and in voluntary organisations. The Government is committed to: – securing comprehensive and enforceable civil rights for disabled people – improving services for disabled people, taking into account their needs and wishes – and improving information about services. The guide gives information about services from Government departments and agencies, the NHS and local government, and voluntary organisations. It covers everyday needs such as money and housing as well as opportunities for holidays and leisure. It includes phone numbers and publications and a list of organisations.Audio cassette and Braille versions are also available. I hope that you will find it a practical source of useful information. John Hutton Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Health Margaret Hodge Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Employment and Equal Opportunities, Minister for Disabled People The Disability Discrimination Act The Disability Discrimination Act became law in November 1995 and many of its main provisions came into force on 2 December 1996.The Act has introduced new rights and measures aimed at ending the discrimination which many disabled people face. Disabled people now have new rights in the areas of employment; getting goods and services; and buying or renting property.Further rights of access to goods and services to protect disabled people from discrimination will be phased in. -

MGLA260719-8697 Date

Our ref: MGLA260719-8697 Date: 22 August 2018 Dear Thank you for your request for information which the GLA received on 26 June 2019. Your request has been dealt with under the Environmental Information Regulations (EIR) 2004. Our response to your request is as follows: 1. Please provide the precise number and list of locations/names of primary and secondary schools in London where air pollution breaches legal limit, according to your most recent data (I believe the same metric has been used across the years, of annual mean limit of 40ug/m3 NO2, but please clarify). If you are able to provide more recent data without breaching the s12 time limit please do. If not, please provide underlying data from May 2018 (see below). Please provide as a spreadsheet with school name, pollution level, and any location information such as borough. This data is available on the London datastore. The most recent available data is from the London Atmospheric Emission Inventory (LAEI) 2016 and was published in April 2019. The data used for the 2018 report is LAEI 2013. Please find attached a list and a summary of all Educational Establishments in London and NO2 levels based on both the LAEI 2013 update and LAEI 2016. The list has been taken from the register of educational establishments in England and Wales, maintained by the Department for Education, and provides information on establishments providing compulsory, higher and further education. It was downloaded on 21/03/2019, just before the release of the LAEI 2016. The attached spreadsheet has recently been published as part of the LAEI 2016 stats on Datastore here. -

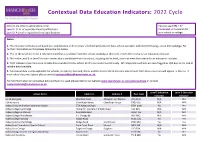

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Choose a Wandsworth SECONDARY SCHOOL

APPLY BY 31 OCTOBER 2021 Choose a Wandsworth SECONDARY SCHOOL A guide for admission to secondary schools Designed and produced by Wandsworth Design & Print. [email protected] in Wandsworth in September 2022. CS.16 (8.21) Contents Introduction 1 About this booklet 2 Before you apply 2 Choosing and applying How and when to apply 3 The variety of schools in Wandsworth and location map 4 The variety of school places 5 Section 1 Open days and evenings 6 The transfer timetable 7 Applying for places - step by step 8-15 Frequently asked questions 16 The schools 17 The schools - Detailed information on all the schools including Section 2 admission criteria and appeal arrangements 18-39 Admission of children already of secondary school age 40 Special schools and other information 41 Other information 42 Children with special educational needs 43 Section 3 Special Schools 44-46 Financial assistance 47 Education for 16-19 year olds 48 The Wandsworth Year 6 Test 49 Section 4 The Wandsworth Year 6 Test 50-51 Schools in other boroughs 52 If there are any further questions you want to ask, or if there is anything you do not understand, staff in the Pupil Services Section will be pleased to help you. You can contact them by: • Telephoning: (020) 8871 7316 • Email: [email protected] Website: www.wandsworth.gov.uk/admissions • Writing to: Pupil Services Section Children’s Services Department Town Hall Extension Wandsworth High Street London SW18 2PU Introduction This booklet is intended to guide Wandsworth parents and their children through the admissions process for September 2022 and to help them to make well-informed choices from the wide range of excellent secondary schools in the borough. -

Job Search: the Real Story

Job Search: The Real Story A toolkit for blind and partially sighted jobseekers, facilitators and employers Job Search: The Real Story A toolkit for blind and partially sighted jobseekers, facilitators and employers Contents Foreword .................................................................................................. 5 Acknowledgements................................................................................. 6 Visage developmental partners ......................................................... 6 Supporting national employers........................................................... 6 Supporting specialist organisations ................................................... 6 Section one: Using the toolkit................................................................ 7 1.1. Introduction ................................................................................. 7 1.2. User guide................................................................................... 8 Who can use the toolkit? ................................................................ 8 What do you do with the toolkit? .................................................... 8 User guide for individual jobseekers ............................................ 10 User guide for facilitators of events.............................................. 11 1.3. Aims and objectives .................................................................. 13 Aims of the toolkit ......................................................................... 13 Learning outcomes...................................................................... -

Progress in Sight

Progress in sight National standards of social care for visually impaired adults The Association of Directors of Social Services October 2002 Alternative formats This document is also available in large print, Braille and on audio tape. It can be supplied on a floppy disk in pdf format for a Windows PC or Apple Macintosh computer (requires Adobe Acrobat™ Reader) or as a Microsoft Word document or a plain text file. It can be obtained in any of these formats for £10 plus postage and packing from: RNIB Customer Services Telephone: 08457 023153 PO Box 173 Fax: 01733 371555 Peterborough PE2 6WS Minicom: 0845 758 5691 E-mail: [email protected] It can also be downloaded from the following Web sites on the Internet: www.adss.org.uk/eyes.shtml (The Association of Directors of Social Services) www.guidedogs.org.uk (The Guide Dogs for the Blind Association) www.rnib.org.uk (The Royal National Institute of the Blind) Copyright notice This publication is free from copyright restrictions. It can be copied in whole or in part and used to train staff and volunteers or for any other purpose that results in improved services for visually impaired people. However, any material that is used in this way should acknowledge this publication as its source. Edited by Andrew Northern ([email protected]) Designed by Ray Hadlow FCSD ([email protected]) Typeset in Stone Sans by DP Press, Sevenoaks, Kent (www.dppress.co.uk) Printed by CW Print Group, Loughton, Essex (www.cwprint.co.uk) Published in October 2002 by the Disabilities Committee of the Association of Directors of Social Services, Riverview House, Beaver Lane, London W6 9AR The Association of Directors of Social Services is a registered charity, number 299154 2 Contents Introduction 4 Acknowledgements 5 Notes on terminology 6 The extent of the problem 8 The purpose of the national standards 10 The principles underpinning the national standards 12 The national standards — A summary 14 Part One. -

Use of Contextual Data at the University of Warwick

Use of contextual data at the University of Warwick The data below will give you an indication of whether your school meets the eligibility criteria for the contextual offer at the University of Warwick. School Name Town / City Postcode School Exam Performance Free School Meals 'Y' indicates a school with below 'Y' indcicates a school with above Schools are listed on alphabetical order. Click on the arrow to filter by school Click on the arrow to filter by the national average performance the average entitlement/ eligibility name. Town / City. at KS5. for Free School Meals. 16-19 Abingdon - OX14 1RF N NA 3 Dimensions South Somerset TA20 3AJ NA NA 6th Form at Swakeleys Hillingdon UB10 0EJ N Y AALPS College North Lincolnshire DN15 0BJ NA NA Abbey College, Cambridge - CB1 2JB N NA Abbey College, Ramsey Huntingdonshire PE26 1DG Y N Abbey Court Community Special School Medway ME2 3SP NA Y Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds LS16 5EA Y N Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College Stoke-on-Trent ST2 8LG NA Y Abbey Hill School and Technology College, Stockton Stockton-on-Tees TS19 8BU NA Y Abbey School, Faversham Swale ME13 8RZ Y Y Abbeyfield School, Chippenham Wiltshire SN15 3XB N N Abbeyfield School, Northampton Northampton NN4 8BU Y Y Abbeywood Community School South Gloucestershire BS34 8SF Y N Abbot Beyne School and Arts College, Burton Upon Trent East Staffordshire DE15 0JL N Y Abbot's Lea School, Liverpool Liverpool L25 6EE NA Y Abbotsfield School Hillingdon UB10 0EX Y N Abbs Cross School and Arts College Havering RM12 4YQ N -

June 2017 (PDF)

Date Amount Supplier Name Spend 20170601 3,915.65 KEEGANS LTD Professional Fees 20170601 70,489.21 H A MARKS LIMITED Construction Work 20170601 603.9 PERSONAL SECURITY SERVICE LTD S17 - Transport 20170601 1,470.00 MRS C C VON EISENHEART-GOODWIN Independent - Day & Boarding 20170601 711.36 RRC (RRCONSULTANCY) LTD General Contract Work 20170601 78,245.48 Cora Foundation Secure Accommodation Welfare 20170601 850 Speak2me Ltd Independent - Day & Boarding 20170601 2,039.36 PENDERELS TRUST LIMITED - DP Direct Payments to Clients 20170602 29,124.81 THE ROCHE SCHOOL Grants Early Yrs Providrs 3Yr+ 20170602 3,771.81 HAYES COURT NURSING HOME External Residential Care 20170602 16,640.77 NURSERY ASPIRE Grants Early Yrs Providrs 3Yr+ 20170602 7,770.15 POPPITS DAY NURSERY Private Providers 2 Year Olds 20170602 7,169.60 YUKON DAY NURSERY Private Providers 2 Year Olds 20170602 14,968.80 PROSPECT HOUSE SCHOOL Grants Early Yrs Providrs 3Yr+ 20170602 18,182.96 ABACUS EARLY LEARNING NURSERY Grants Early Yrs Providrs 3Yr+ 20170602 36,513.36 NODDY'S DAY NURSERY Grants Early Yrs Providrs 3Yr+ 20170602 19,379.48 NSL LIMITED Materials 20170602 6,738.22 BRIGHT HORIZONS FAMILY SOLUTIONS Grants Early Yrs Providrs 4Yr+ 20170602 660 MRS C C VON EISENHEART-GOODWIN Independent - Day & Boarding 20170602 4,473.76 THE PARK GARDENS CHILDCARE LTD Grants Early Yrs Providrs 3Yr+ 20170602 5,595.25 NIGHTINGALE DAY NURSERY Grants Early Yrs Providrs 3Yr+ 20170602 16,139.92 ROOKSTONE ROAD PLAYGROUP Private Providers 2 Year Olds 20170602 554.4 AA DRIVETECH Payments To Sub-Contractors -

Choose a Wandsworth Secondary School 2018

Choose a Wandsworth APPLY BY 31 OCTOBER SECONDARY 2018 SCHOOL A guide for admission to secondary schools in Wandsworth in September 2019 Contents Introduction 1 About this booklet 2 Before you apply 2 Choosing and applying How and when to apply 3 Online application - step by step 4-5 The variety of schools in Wandsworth and location map 6 The variety of school places 7 Section 1 Open days and evenings 8 The transfer timetable 9 Applying for places - step by step 10-17 Frequently asked questions 18 The schools 19 The schools - Detailed information on all the schools including Section 2 admission criteria and appeal arrangements 20-41 Admission of children already of secondary school age 42 Facts and Figures 43 GCSE results 2017 44 Other information 44 Children with special educational needs 45 Section 3 Special Schools 46 Financial assistance 49 Education for 16-19 year olds 50 The Wandsworth Year 6 Test 53 Section 4 The Wandsworth Year 6 Test 54 Schools in other boroughs 56-58 If there are any further questions you want to ask, or if there is anything you do not understand, staff in the Pupil Services Section will be pleased to help you. You can contact them by: • Telephoning: (020) 8871 7316 • Email: [email protected] Website: www.wandsworth.gov.uk/admissions • Writing to: Pupil Services Section Children’s Services Department Town Hall Extension Wandsworth High Street London SW18 2PU • Visiting: The Customer Centre, Town Hall Extension, Wandsworth High Street, London SW18 2PU Introduction This booklet is intended to guide Wandsworth parents and their children Meetings For Parents through the admissions process for September 2019 and to help them to make well-informed choices from the wide range of excellent secondary You are invited to attend one of schools in the borough. -

Eligible If Taken A-Levels at This School (Y/N)

Eligible if taken GCSEs Eligible if taken A-levels School Postcode at this School (Y/N) at this School (Y/N) 16-19 Abingdon 9314127 N/A Yes 3 Dimensions TA20 3AJ No N/A Abacus College OX3 9AX No No Abbey College Cambridge CB1 2JB No No Abbey College in Malvern WR14 4JF No No Abbey College Manchester M2 4WG No No Abbey College, Ramsey PE26 1DG No Yes Abbey Court Foundation Special School ME2 3SP No N/A Abbey Gate College CH3 6EN No No Abbey Grange Church of England Academy LS16 5EA No No Abbey Hill Academy TS19 8BU Yes N/A Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College ST3 5PR Yes N/A Abbey Park School SN25 2ND Yes N/A Abbey School S61 2RA Yes N/A Abbeyfield School SN15 3XB No Yes Abbeyfield School NN4 8BU Yes Yes Abbeywood Community School BS34 8SF Yes Yes Abbot Beyne School DE15 0JL Yes Yes Abbots Bromley School WS15 3BW No No Abbot's Hill School HP3 8RP No N/A Abbot's Lea School L25 6EE Yes N/A Abbotsfield School UB10 0EX Yes Yes Abbotsholme School ST14 5BS No No Abbs Cross Academy and Arts College RM12 4YB No N/A Abingdon and Witney College OX14 1GG N/A Yes Abingdon School OX14 1DE No No Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX Yes Yes Abraham Guest Academy WN5 0DQ Yes N/A Abraham Moss Community School M8 5UF Yes N/A Abrar Academy PR1 1NA No No Abu Bakr Boys School WS2 7AN No N/A Abu Bakr Girls School WS1 4JJ No N/A Academy 360 SR4 9BA Yes N/A Academy@Worden PR25 1QX Yes N/A Access School SY4 3EW No N/A Accrington Academy BB5 4FF Yes Yes Accrington and Rossendale College BB5 2AW N/A Yes Accrington St Christopher's Church of England High School