Crafting Alliances

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College News October 2018

30 YEARS 1988 - 2018 QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OCTOBER EDITION 2018 Congratulations to this year’s Honorary Fellows, Professor Harminder Dua, Miss Marcia Zondervan and the diplomates receiving their award at the RCOphth Admissions Ceremony in September. PAGE 4 A SAS perspective Jugnoo Rahi Trainee Knowledge PAGE 6 New PAGE 15 New PAGE 18 How to to the NHS Chair, Academic mix research with subcommittee clinical training college news Dear fellow members, “Treating clinicians can lawfully choose Avastin for ophthalmic use on grounds of cost” Contents The 21st of September 2018 will live long in the memory of those who have campaigned 3 Awards galore! to be allowed to use Avastin (bevacizumab) 5 2018 Admissions as treatment for wet age-related macular Ceremony degeneration (ARMD). The landmark ruling by 6 New to the NHS - A Mrs Justice Whipple has brought clarity to the SAS Perspective interpretation of the national and European 7 Focus Managing legislation and should be read in full by all refractive surprise ophthalmologists. The College has issued a briefing note via Eye- 11 Museum Piece Mail to help answer some of the comments Births and Books in Whilst some may consider this a victory and concerns raised by members and I wish Ophthalmology 1818 over ‘Big Pharma’, we must not forget that members to continue to contribute to the 15 Jugnoo Rahi pharmaceutical companies are responsible discussions around Avastin. - New Academic for the development of the drugs we now use subcommittee chair to prevent blindness. It is essential that we Please do contact me at president@rcophth. 17 Ophthalmologists in recognise their vital role in eye health and ac.uk and I will do my best to answer your Training continue to work closely with them in future. -

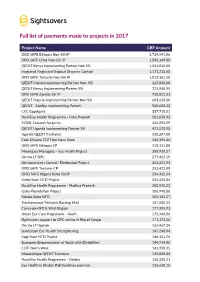

Full List of Payments Made to Projects in 2017

Full list of payments made to projects in 2017 Project Name GBP Amount DfID SAFE Ethiopia Non-SSI IP 3,724,841.06 DfID SAFE Chad Non-SSI IP 1,893,149.00 QEDJT Kenya Implementing Partner Non SSI 1,261,816.00 Inegrated Neglected Tropical Diseases Control 1,171,233.68 DfID SAFE Tanzania Non-SSI IP 1,013,161.50 QEDJT Malawi Implementing Partner Non-SSI 825,000.00 QEDJT Kenya Implementing Partner SSI 721,960.95 DfID SAFE Zambia SSI IP 720,031.31 QEDJT Nigeria Implementing Partner Non SSI 603,658.00 QEDJT - Zambia Implementing Partner 580,608.32 CEC Gopalganj 557,718.51 Rural Eye Health Programme - Uttar Pradesh 501,838.92 87001 Cataract Surgeries 462,293.59 QEDJT Uganda Implementing Partner SSI 421,538.90 Uganda QEDJT Trachoma 380,297.00 Cote D'Ivoire CDTI Northern Zone 340,192.64 DfID SAFE Ethiopia CP 318,111.00 Mwangaza Morogoro – Eye Health Project 289,938.37 Oncho LF DRC 277,423.19 Onchocerciasis Control/ Elimination Project 261,231.91 DfID SAFE Tanzania CP 252,433.00 DFID SAFE Nigeria Kano SSI IP 234,412.34 Kebbi State NTD Project 225,634.84 Rural Eye Health Programme - Madhya Pradesh 208,938.23 Gates Foundation Project 206,998.88 Sokoto State NTD 203,103.27 Trachomatous Trichiasis Backlog Mali 187,888.23 Cameroon NTDs West Region 177,395.91 Urban Eye Care Programme - South 175,348.06 Sightsavers support to OPC-oncho in Rep of Congo 171,173.56 Oncho LF Uganda 165,967.34 Sunderban Eye Health Strengthening 147,240.04 Kogi State NTD Project 146,131.74 Economic Empowerment of Youth with Disabilities 144,914.08 CDTI North West 141,950.35 Mozambique -

Sightsavers-Annual-Review-2012.Pdf

Annual review 2012 Contents President’s welcome 3 Our mission, our methods 4 How we measure our progress 5 How we prevent and cure blindness 7 We invest in training eye health workers and volunteers, in-country 8 We aim to eliminate blinding trachoma from 24 countries 11 We plan on eliminating river blindness from 14 countries 12 We work for long-term change 14 We work to make education accessible to blind children 16 We work towards social inclusion 18 Where we work 20 Bereket and Besufigad Funding innovation 21 Sisay, from Booddachi town in the Oromia Raising our international profile 23 region of Ethiopia both What our supporters say about us 24 suffer from trachoma. Without vital antibiotic Income and expenditure 25 treatment they would both face a future of blindness. A word from our Chief Executive 26 Thank you 27 © Dominic Nahr / Magnum / Sightsavers 2 Annual review 2012 Sightsavers President HRH Princess Alexandra © Dominic Nahr / Magnum / Sightsavers 3 © Zul Mukhida / Sightsavers © Zul The Sightsavers SIM Card Our mission, (Strategy Implementation and Monitoring Card) our methods Sightsavers’ strategy map Our vision: No one is blind from avoidable causes; visually impaired people participate equally in society Sightsavers’ vision is of a Our focus isn’t just on short-term goals – we Our mission: To eliminate avoidable blindness and promote equality of opportunity for disabled people are looking to make long-term change in the world where no one is blind countries where we work. Sightsavers is working with the Kamuli Visually -

Why Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Are Vital for Eliminating Neglected Tropical Diseases

WASH Why water, sanitation and hygiene are vital for eliminating neglected tropical diseases Brief Now is the time to say goodbye to neglected tropical diseases © Sightsavers/Jason Mulikita © Sightsavers/Jason Children from Ngangula Primary School carrying water to school in Chikankata, Zambia. Contents 4 14 Introduction Using WASH data to combat NTDs 5 17 WASH: the facts Social behaviour change communication: the practices that underpin WASH 6 WASH: our key programmes 18 Preparing for the future 8 Working with communities: helping neighbours and friends stay 19 trachoma free References 9 The challenges of delivering WASH 10 Why WASH is worth the investment 11 Encouraging collaboration between the WASH and NTD sectors Cover image 12 Peace Kiende, 11, a student at Developing tools to support Antuaduru Primary School sings a WASH programmes song that helps her remember how to wash her hands and face, as part of the Sightsavers’ WASH project in Meru, Kenya. ©Sightsavers/Andrew Renneisen 3 Introduction In communities where water is scarce, supplies are often reserved for drinking or farming, meaning hygiene and sanitation are sidelined. Poor hygiene is linked to people in people’s habits, community, culture or contracting and spreading bacterial and national tradition, but these practices are parasitic infections, including a number potentially harmful because they help of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). trachoma and other NTDs to spread. Improving access to clean water, good sanitation and hygiene (often referred Closely linked to some of our WASH work to by the acronym ‘WASH’) is critical in is the WHO-approved ‘SAFE’ strategy preventing and treating these diseases. -

UK Eye Care Services Project Phase One: Systematic Review of the Organisation of UK Eye Care Services

UK Eye Care Services Project Phase One: Systematic Review of the Organisation of UK Eye Care Services University of Warwick September 2010 (Revised February 2011) Dr Carol Hawley Helen Albrow Dr Jackie Sturt Lynda Mason UK Eye Care Services Project Contents Phase One: Systematic Review of the Organisation of UK Eye Care Services Study team i Acknowledgements i Glossary of abbreviations ii Executive Summary 1 1. Background to current organisation of UK eye care services 4 Devolution in Scotland and Wales 6 Global thinking surrounding eye care services and the UK response 8 Other ophthalmic roles 9 Generalisability of care pathways 11 Report Aim 11 2. Methods 12 2.1 Data searches 12 2.2 Data Extraction 14 3. Results 15 3.1 Report organisation 15 3.2 Summary of ‘black’ literature 17 Optometrists in primary care 18 Optometrists within the HES 19 Combined eye examination and referral initiatives for all eye conditions 22 Referral initiatives for all eye conditions 23 Referral quality and frequencies for all eye conditions 25 Glaucoma 28 Ocular Hypertension (OHT) 40 Cataract 41 Posterior Capsular Opacification 47 Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) 49 Blood Glucose screening 60 Optometric Prescribing 61 Low Vision Services 64 Paediatric eye care services 67 Melanoma 71 Flashes and floaters 72 Critique of the COSI concept (Community Optometrists with a Special Interest) 74 Optometric technological comparison studies 75 4. Conclusions from the literature 76 5. References 78 UK Eye Care Services Project Appendices Phase One: Systematic Review of the Organisation -

Fight for Sight Is the UK's Largest Charity Funding Pioneering Eye

Fight for Sight is the UK’s largest charity funding pioneering eye research since 1965. Our mission Fight for Sight funds pioneering research to prevent sight loss and treat eye disease. Our vision A future everyone can see. Fight£3.3m for Sight committed to research in 2017/18 Fight£8m for Sight commitment to active research projects Number of active research projects 166 Number of funded institutions 49 5 49 49 2 49 7 49 3 49 3 49 2 49 7 49 1 49 10 49 5 49 4 Numbers of patients in clinical studies funded by Fight for Sight Number16,230 of patients Number87 of studies recruited into NIHR on the NIHR CRN supported studies funded portfolio funded partly partly or wholly by or wholly by Fight for Sight Fight for Sight between between April 2008 April 2008 and and January 2018 January 2018 Number71 of sites Number23 of studies from which NIHR has open on the NIHR recruited participants for CRN portfolio studies funded partly or funded partly or wholly wholly by Fight for Sight by Fight for Sight between April 2008 as of January 2018 and January 2018 National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network (CRN) Charity partners Fight for Sight is very pleased to be collaborating with other charities in the sector. Fight for Sight is the UK’s largest charity funding pioneering eye research since 1965. Estimated prevalence of main eye diseases in the UK Age-related macular degeneration 600,000 people Glaucoma 500,000 people Cataract 500,000 people Diabetic retinopathy 144,000 people How many people fear losing their sight? of25% the adult population are not having an eye test of people78% stated every 2E years. -

2003 Annual Report

building together 2003 Annual Report who we are and what we do Who We Are: INDEPENDENT SECTOR is committed to strengthening, empowering, and partnering with nonprofit and philan- thropic organizations in their work on behalf of the public good. Its membership of nonprofit organizations, foundations, and corporate philanthropy programs collectively represents tens of thousands of charitable groups serving every cause in every region of the country, as well as millions of donors and volunteers. What We Do: INDEPENDENT SECTOR works to promote a just and inclusive society of active citizens, healthy communities, and a vibrant democracy by: •Creating a meeting ground for nonprofit and philan- thropic leaders to take collective action on issues that have an impact on the independent sector and its work; •Promoting policies that enable nonprofits to advocate and engage with public officials on a nonpartisan basis; • Encouraging the sector to meet the highest standards of ethical practice, value, and effectiveness; • Analyzing and interpreting relevant research and other data concerning the voluntary sector; and • Serving as the voice of the independent sector to the media, government, business, and international volun- tary communities. Our Vision: A just and inclusive society of active citizens, vibrant communities, effective institutions, and a healthy democracy. Our Mission: To promote, strengthen, and advance the nonprofit and philanthropic community to foster private initiative for the public good. INDEPENDENT SECTOR and the independent sector The INDEPENDENT SECTOR name celebrates the vast network of voluntary organizations, foundations, religious congregations, social welfare groups, and corporate giving programs working together to improve the lives of people across the United States and around the world. -

CHICAGO CHILDREN to DESIGN DREAM PLAYGROUND: the CATALYST SCHOOLS, BLUE CROSS and BLUE SHIELD of ILLINOIS and Kaboom! HOST DESIGN DAY for NEW PLAYGROUND

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Michael Fehrenbach, The Catalyst Schools, 773-897-5817, [email protected] Mary Ann Schultz, BCBSIL, 312-653-6701, [email protected] Alyssa Ross, KaBOOM!, 202-464-6162, [email protected] CHICAGO CHILDREN TO DESIGN DREAM PLAYGROUND: THE CATALYST SCHOOLS, BLUE CROSS AND BLUE SHIELD OF ILLINOIS AND KaBOOM! HOST DESIGN DAY FOR NEW PLAYGROUND WHAT: The Catalyst Schools, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois, and organizers from KaBOOM! will host a design day for children at Sojourn on Monday, June 3, 2013. Children from The Catalyst Schools–Maria, will put crayon to paper and draw their dream playgrounds, which will ultimately become a reality. Elements from the children’s drawings will be incorporated into the final design for the new playground to be built on Saturday, July 20, 2013, at Catalyst–Maria. Design day will be the first meeting of the playground planning committee that will work for the next seven weeks to plan and prepare for the construction of the new playground. WHY: Today’s kids spend less time playing outside than any previous generation in part because only 1-in-5 children live within walking distance of a park or playground. This play deficit is having profound consequences for kids physically, emotionally and cognitively. Children need a place to play every day in order to be active and healthy, something KaBOOM! has been committed to since 1996. The new playground will provide more than 540 children in the neighborhood with a safe place to play. This will be a new playground for the school, as there is not currently playground equipment on-site. -

Eye Research Charity Looking for Pioneering Researchers in Scotland Fight for Sight Partners with Chief Scientist Office to Fund Research in Scotland

Immediate release Eye research charity looking for pioneering researchers in Scotland Fight for Sight partners with Chief Scientist Office to fund research in Scotland Fight for Sight, the UK’s leading eye research charity, has partnered with the Scottish Government’s Chief Scientist Office (CSO) to help address age-related eye diseases. The charity is calling for research applications from Scottish based researchers for a grant of up to £200,000 for up to three years. The grant will support research to help address age- related eye diseases and conditions as well as projects focusing on the association of visual impairment with other long-term conditions, such as dementia, stroke or diabetes. The closing date for Fight for Sight/ CSO Project grant applications is 5pm on 1 November 2017. Supporting Quote: Dr Alan McNair, Senior Research Manager at the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office “CSO is delighted to partner with Fight for Sight in this exciting research funding initiative. Age related eye diseases can severely impact patients and those close to them. Research is essential if we are to develop a better understanding of the impact of these conditions and develop effective new treatments”. Michele Acton, Chief Executive of Fight for Sight “It is only through funding eye research that we will be able to address age-related sight loss. Partnering with the CSO will bring us closer to our goals to the benefit of people in Scotland and worldwide.” Online Resources: W: http://www.fightforsight.org.uk/apply-for-funding/funding-opportunities/fight-for-sight-cso- project-grant/ T: @fightforsightUK F: https://www.facebook.com/fightforsightuk ENDS About Fight for Sight 1. -

A Practical Guide for Disabled People

HB6 A Practical Guide for Disabled People Where to find information, services and equipment Foreword We are pleased to introduce the latest edition of A Practical Guide for Disabled People. This guide is designed to provide you with accurate up-to-date information about your rights and the services you can use if you are a disabled person or you care for a disabled relative or friend. It should also be helpful to those working in services for disabled people and in voluntary organisations. The Government is committed to: – securing comprehensive and enforceable civil rights for disabled people – improving services for disabled people, taking into account their needs and wishes – and improving information about services. The guide gives information about services from Government departments and agencies, the NHS and local government, and voluntary organisations. It covers everyday needs such as money and housing as well as opportunities for holidays and leisure. It includes phone numbers and publications and a list of organisations.Audio cassette and Braille versions are also available. I hope that you will find it a practical source of useful information. John Hutton Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Health Margaret Hodge Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Employment and Equal Opportunities, Minister for Disabled People The Disability Discrimination Act The Disability Discrimination Act became law in November 1995 and many of its main provisions came into force on 2 December 1996.The Act has introduced new rights and measures aimed at ending the discrimination which many disabled people face. Disabled people now have new rights in the areas of employment; getting goods and services; and buying or renting property.Further rights of access to goods and services to protect disabled people from discrimination will be phased in. -

Overseas Programme Department

OVERSEAS PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT Staff Members and Contact Details Updated 04/03/03 HAYWARDS HEATH OFFICE Sight Savers International, Grosvenor Hall, Bolnore Road, Haywards Heath, West Sussex, RH16 4BX Tel: +1444 44 66 00 OPD Fax: +1444 44 66 77 e-mail: [email protected] EAST, CENTRAL & SOUTHERN AFRICA REGIONAL OFFICE (ECSA) Sight Savers International, East, Central & Southern Africa Regional Office PO Box 34690, 00100 GPO, Nairobi, Kenya Street Address (for DHL etc): Barclay House, Mai Mahiu Road, Off Langata Road, Nairobi West, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: 00 254 2 502750 Fax: 00 254 2 609623 00 254 2 503835 00 254 2 601204 e-mail: [email protected] NB: Mobiles to be used in emergencies or when switchboard out of order Kenya (Country) Office Sight Savers International, Kenya Country Office PO Box 10417, 00100 GPO, Nairobi, Kenya Street Address (for DHL etc): Barclay House, Mai Mahiu Road, Off Langata Road, Nairobi West, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: 00 254 2 601209 Fax: 00 254 2 505548 e-mail: [email protected] Malawi Country Office Office Address: Sight Savers International, Malawi Country Office, Area 3/310, Baron Avenue, P/Bag A197, Lilongwe, Malawi Tel: 002651 750453 Fax: 00 2651 750450 002651 758210 e-mail: [email protected] Uganda Office Address: Sight Savers International, 3rd Floor, Colline House, Pilkington Road, Kampala, Uganda Tel: 00 256 41 230299 Fax: 00 256 41 230338 e-mail: [email protected] Tanzania Office Address: Sight Savers International, PO Box 2513, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Street Address for DHL: Plot No. 327, -

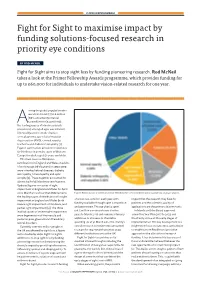

Fight for Sight to Maximise Impact by Funding Solutions-Focused Research in Priority Eye Conditions

25 YEARS IN OPHTHALMOLOGY Fight for Sight to maximise impact by funding solutions-focused research in priority eye conditions BY ROD MCNEIL Fight for Sight aims to stop sight loss by funding pioneering research. Rod McNeil takes a look at the Primer Fellowship Awards programme, which provides funding for up to £60,000 for individuals to undertake vision-related research for one year. mong the global population who were blind in 2015 (36.0 million [80% uncertainty interval A12·9 million to 65.4 million]), the leading causes of blindness (crude prevalence) among all ages was cataract, followed by uncorrected refractive error, glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), corneal opacity, trachoma and diabetic retinopathy [1]. Figure 1 summarises prevalence estimates for blindness in 2015 by cause in Western Europe for adults aged 50 years and older. The main causes of blindness certifications in England and Wales in adults of working age (16-64 years) in 2009-2010 were inherited retinal diseases, diabetic retinopathy / maculopathy and optic atrophy [2]. These together accounted for almost half of all blindness certifications. Updated figures on causes of sight impairment in England and Wales for April 2012-March 2013 show that AMD remains Figure 1: Western Europe: projected prevalence of blindness (VA <3/60 in the better eye) by cause among adults ≥50 years [1]. the leading cause of certifications for sight of around £3-4 million each year, with impact that the research may have for impairment in England and Wales (both funding available through open competition patients and the scientific quality of severe sight impairment or blindness, and partial sight impairment) [3].