How Australia Led the Way: Dora Meeson Coates and British Suffrage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Muriel Matters Society Epistle

The Muriel Matters Proudly supported by: Society Epistle No: 16 (October 2012) Hello Members and Friends! Our next event will be to commemorate the 104th Anniversary of The Grille Protest on Sunday, 4 November, 2012 from 1.00pm to 3.00pm at MRC/Lions Community Centre, 23 Coglin Street, Adelaide 5000 (located between Gouger and Wright Streets, near Central Market). RSVP (helpful!) to 0437 656 700 or [email protected]. Mr Ron Potts, a highly regarded speaker, has kindly agreed to bring along his ‘magic lantern’ and address us on the history of the ‘kinematograph’ - the technology Muriel brought with her to Australia to ‘vividly illustrate with pictures’ her lectures during the 1910 Tour to Perth, Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney. Accompanied by her great friend, Violet Tillard, (who may have operated the lantern), the tour informed her eager audiences about her adventures in England, assisting British women to secure the franchise. The secrets of ‘magic lantern’ operation will be revealed!! An event – like the original – not to be missed! (Invitations have already been emailed to members who have supplied their email address. If you didn’t receive an email, and have access to email, please advise your email address asap. Newsletters can then also be emailed. Thanks!) Memberships Due: for those yet to renew, payments can be made at the meeting or by cheque or direct bank transfer via the form enclosed. Please remember - your subs keep Muriel projects happening – thank you! UK News The recent London Olympic Opening Ceremony did feature a vignette on suffrage. Women and girls, in Edwardian costume, carried a suffrage banner in the segment choreographed by Australian Danny Boyle, while the story of the struggle for Votes for Women was narrated by Sir Kenneth Branagh. -

Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign George David Schieffler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2017 Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign George David Schieffler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Schieffler, George David, "Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 2426. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2426 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by George David Schieffler The University of the South Bachelor of Arts in History, 2003 University of Arkansas Master of Arts in History, 2005 August 2017 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________________ Dr. Daniel E. Sutherland Dissertation Director ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Dr. Elliott West Dr. Patrick G. Williams Committee Member Committee Member Abstract “Civil War in the Delta” describes how the American Civil War came to Helena, Arkansas, and its Phillips County environs, and how its people—black and white, male and female, rich and poor, free and enslaved, soldier and civilian—lived that conflict from the spring of 1861 to the summer of 1863, when Union soldiers repelled a Confederate assault on the town. -

Liña Do Tempo

Documento distribuído por Álbum de mulleres Liña do tempo http://culturagalega.org/album/linhadotempo.php 11ª versión (13/02/2017) Comisión de Igualdade Pazo de Raxoi, 2º andar. 15705 Santiago de Compostela (Galicia) Tfno.: 981957202 / Fax: 981957205 / [email protected] GALICIA MEDIEVO - No mundo medieval, as posibilidades que se ofrecen ás mulleres de escoller o marco en que han de desenvolver o seu proxecto de vida persoal son fundamentalmente tres: matrimonio, convento ou marxinalidade. - O matrimonio é a base das relacións de parentesco e a clave das relacións sociais. Os ritos do matrimonio son instituídos para asegurar un sistema ordenado de repartimento de mulleres entre os homes e para socializar a procreación. Designando quen son os pais engádese outra filiación á única e evidente filiación materna. Distinguindo as unións lícitas das demais, as crianzas nacidas delas obteñen o estatuto de herdeiras. - Século IV: Exeria percorre Occidente, á par de recoller datos e escribir libros de viaxes. - Ata o século X danse casos de comunidades monásticas mixtas rexidas por abade ou abadesa. - Entre os séculos IX e X destacan as actividades de catro mulleres da nobreza galega (Ilduara Eriz, Paterna, Guntroda e Aragonta), que fan delas as principais e máis cualificadas aristócratas galegas destes séculos. - Entre os séculos IX e XII chégase á alianza matrimonial en igualdade de condicións, posto que o sistema de herdanza non distingue entre homes e mulleres; o matrimonio funciona máis como instrumento asociativo capaz de crear relacións amplas entre grupos familiares coexistentes que como medio que permite relacións de control ou protección de carácter vertical. - Século X: Desde mediados de século, as mulleres non poden testificar nos xuízos e nos documentos déixase de facer referencia a elas. -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

Nothing Complicated About Ordinary Equality: Alice Paul and Self-Sacrifice

Nothing Complicated About Ordinary Equality: Alice Paul and Self-Sacrifice Handout A: Narrative BACKGROUND The organized reform movement for American women’s economic and legal rights, including suffrage, is commonly dated from the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. At this meeting of about 300 people, Elizabeth Cady Stanton read her Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions, and 100 attendees signed the document. Stanton met Susan B. Anthony three years later and for the next half century the two women collaborated in a powerful partnership focused on numerous social reforms including the abolition of slavery, support for temperance, and pursuit of legal equality for women. In 1885, Alice Paul was born to a Quaker family in New Jersey, and as a small child she attended women’s suffrage events with her mother. She would become one of the most powerful voices for women’s rights in the new century, bringing new life to a movement that had stalled out by 1900. NARRATIVE From a young age, Paul demonstrated outstanding academic promise, and though she studied social work and served the poor at settlement houses, she disdained the typical professions open to women: nursing, teaching, and social work. She later explained, “I knew in a very short time I was never going to be a social worker, because I could see that social workers were not doing much good in the world…you couldn’t change the situation by social work.” After completing a bachelor’s degree in biology and then a master’s degree in sociology, Paul sailed to Great Britain in 1907. -

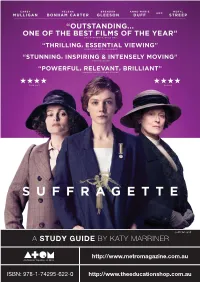

Suffragette Study Guide

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-622-0 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 106 minutes » SUFFRAGETTE Suffragette (2015) is a feature film directed by Sarah Gavron. The film provides a fictional account of a group of East London women who realised that polite, law-abiding protests were not going to get them very far in the battle for voting rights in early 20th century Britain. click on arrow hyperlink CONTENTS click on arrow hyperlink click on arrow hyperlink 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 19 8. Never surrender click on arrow hyperlink 3 STORY 20 9. Dreams 6 THE SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT 21 EXTENDED RESPONSE TOPICS 8 CHARACTERS 21 The Australian Suffragette Movement 10 ANALYSING KEY SEQUENCES 23 Gender justice 10 1. Votes for women 23 Inspiring women 11 2. Under surveillance 23 Social change SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2015 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION 12 3. Giving testimony 23 Suffragette online 14 4. They lied to us 24 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS 15 5. Mrs Pankhurst 25 APPENDIX 1 17 6. ‘I am a suffragette after all.’ 26 APPENDIX 2 18 7. Nothing left to lose 2 » CURRICULUM LINKS Suffragette is suitable viewing for students in Years 9 – 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, Civics and Citizenship, History, Media, Politics and Sociology. Links can also be made to the Australian Curriculum general capabilities: Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability and Ethical Understanding. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ and curriculum outlines relevant to these studies in their state or territory. -

The Health and Welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: an Overview (Full Publication; 5 May

The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people an overview 2011 The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare is Australia’s national health and welfare statistics and information agency. The Institute’s mission is better information and statistics for better health and wellbeing. © Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2011 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior written permission from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Head of the Communications, Media and Marketing Unit, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, GPO Box 570, Canberra ACT 2601. A complete list of the Institute’s publications is available from the Institute’s website <www.aihw.gov.au>. ISBN 978 1 74249 148 6 Suggested citation Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2011. The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, an overview 2011. Cat. no. IHW 42. Canberra: AIHW. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Board Chair Hon. Peter Collins, AM, QC Director David Kalisch Any enquiries about or comments on this publication should be directed to: Communication, Media and Marketing Unit Australian Institute of Health and Welfare GPO Box 570 Canberra ACT 2601 Phone: (02) 6244 1032 Email: [email protected] Published by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Printed by Paragon Printers Australasia Please note that there is the potential for minor revisions of data in this report. Please check the online version at <www.aihw.gov.au> for any amendments. -

Suffrage and Virginia Woolf 121 Actors

SUFFRAGE AND VIRGINIAWOOLF: ‘THE MASS BEHIND THE SINGLE VOICE’ by sowon s. park Virginia Woolf is now widely accepted as a ‘mother’ through whom twenty- ¢rst- century feminists think back, but she was ambivalent towards the su¡ragette movement. Feminist readings of the uneasy relation betweenWoolf and the women’s Downloaded from movement have focused on her practical involvement as a short-lived su¡rage campaigner or as a feminist publisher, and have tended to interpret her disapproving references to contemporary feminists as redemptive self-critique. Nevertheless the apparent contradictions remain largely unresolved. By moving away from Woolf in su¡rage to su¡rage in Woolf, this article argues that her work was in fact deeply http://res.oxfordjournals.org/ rooted at the intellectual centre of the su¡rage movement. Through an examination of the ideas expressed in A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas and of two su¡rage characters, Mary Datchet in Night and Day and Rose Pargiter in TheYears,it establishes how Woolf’s feminist ideas were informed by su¡rage politics, and illumi- nates connections and allegiances as well as highlighting her passionate resistance to a certain kind of feminism. at Bodleian Library on October 20, 2012 I ‘No other element in Woolf’s work has created so much confusion and disagree- mentamongherseriousreadersasherrelationtothewomen’smovement’,noted Alex Zwerdling in 1986.1 Nonetheless the women’s movement is an element more often overlooked than addressed in the present critical climate. And Woolf in the twentieth- ¢rst century is widely accepted as a ‘mother’ through whom feminists think back, be they of liberal, socialist, psychoanalytical, post-structural, radical, or utopian persuasion. -

MANAGING DISCORD in the AMERICAS Great Britain and the United States 1886-1896

MANAGING DISCORD IN THE AMERICAS Great Britain and the United States 1886-1896 GERER LA DISCORDE DANS LES AMERIQUES La Grande-Bretagne et les Etats-Unis 1886-1896 A Thesis Submitted To the Division of Graduate Studies of the Royal Military College of Canada By Charles Robertson Maier, CD, MA In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2010 ©This Thesis may be used within the Department of National Defence but copyright for open publication remains the property of the author Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-69195-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-69195-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

Women's Political Participation and Representation in Asia

iwanaga The ability of a small elite of highly educated, upper-class Asian women’s political women to obtain the highest political positions in their country is unmatched elsewhere in the world and deserves study. But, for participation and those interested in a more detailed understanding of how women representation strive and sometimes succeed as political actors in Asia, there is a women’s marked lack of relevant research as well as of comprehensive and in asia user-friendly texts. Aiming to fill the gap is this timely and important study of the various obstacles and opportunities for women’s political Obstacles and Challenges participation and representation in Asia. Even though it brings political together a diverse array of prominent European and Asian academicians and researchers working in this field, it is nonetheless a singularly coherent, comprehensive and accessible volume. Edited by Kazuki Iwanaga The book covers a wide range of Asian countries, offers original data from various perspectives and engages the latest research on participation women in politics in Asia. It also aims to put the Asian situation in a global context by making a comparison with the situation in Europe. This is a volume that will be invaluable in women’s studies internationally and especially in Asia. a nd representation representation i n asia www.niaspress.dk Iwanaga-2_cover.indd 1 4/2/08 14:23:36 WOMEN’S POLITICAL PARTICIPATION AND REPRESENTATION IN ASIA Kazuki_prels.indd 1 12/20/07 3:27:44 PM WOMEN AND POLITICS IN ASIA Series Editors: Kazuki Iwanaga (Halmstad University) and Qi Wang (Oslo University) Women and Politics in Thailand Continuity and Change Edited by Kazuki Iwanaga Women’s Political Participation and Representation in Asia Obstacles and Challenges Edited by Kazuki Iwanaga Kazuki_prels.indd 2 12/20/07 3:27:44 PM Women’s Political Participation and Representation in Asia Obstacles and Challenges Edited by Kazuki Iwanaga Kazuki_prels.indd 3 12/20/07 3:27:44 PM Women and Politics in Asia series, No. -

Australian Women, Past and Present

Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Edited by Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein and Mary Tomsic Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Diversity in leadership : Australian women, past and present / Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein, Mary Tomsic, editors. ISBN: 9781925021707 (paperback) 9781925021714 (ebook) Subjects: Leadership in women--Australia. Women--Political activity--Australia. Businesswomen--Australia. Women--Social conditions--Australia Other Authors/Contributors: Damousi, Joy, 1961- editor. Rubenstein, Kim, editor. Tomsic, Mary, editor. Dewey Number: 305.420994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Introduction . 1 Part I. Feminist perspectives and leadership 1 . A feminist case for leadership . 17 Amanda Sinclair Part II. Indigenous women’s leadership 2 . Guthadjaka and Garŋgulkpuy: Indigenous women leaders in Yolngu, Australia-wide and international contexts . 39 Gwenda Baker, Joanne Garŋgulkpuy and Kathy Guthadjaka 3 . Aunty Pearl Gibbs: Leading for Aboriginal rights . 53 Rachel Standfield, Ray Peckham and John Nolan Part III. Local and global politics 4 . Women’s International leadership . 71 Marilyn Lake 5 . The big stage: Australian women leading global change . 91 Susan Harris Rimmer 6 . ‘All our strength, all our kindness and our love’: Bertha McNamara, bookseller, socialist, feminist and parliamentary aspirant . -

To Download MURIEL MATTERS Press

MEDIA KIT (Duration 27 mins) Muriel Matters, (left) ‘Votes for Women’ caravan tour of southeast England, 1908 Rivet Pictures P/L Claire Harris M 0402 280 506 Julia de Roeper M 0418 842 961 Adelaide Studios 226 Fullarton Road Glenside SA 5065 © Rivet Pictures Pty Ltd ONE LINE SYNOPSIS Adelaide-born actress Muriel Matters made international headlines in 1909 as ‘that daring Australian girl’ for her bold escapades in the struggle for women’s rights in Britain. SHORT SYNOPSIS London 1909, an actress from Adelaide makes worldwide headlines after taking to the skies under a 25-metre balloon emblazoned with 'Votes For Women'. Known as 'that daring Australian girl', Muriel Matters is inspired by playwrights, anarchists and revolutionaries to use her performance skills and bravery in the fight for women's rights. LONG SYNOPSIS When Australian actress Muriel Matters arrived in London in 1905 to seek her fortune on the stage, she was astonished to discover that English women didn't yet have the vote. She joined the Suffragette movement and soon became known as 'that daring Australian girl' for her wild exploits: distributing leaflets from a dirigible balloon, touring England to make impassioned speeches from a horse-drawn caravan, and chaining herself to a grille and becoming the first woman to speak in the House of Commons in 1909. Together with other Australian women artists living in London, Muriel made a remarkable contribution to the fight for women's suffrage, but has mysteriously been ignored in the historical record. This film shares Muriel's love of art and performance and tells the story of Muriel and her artistic friends with verve and gusto.