Mccall Phd 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH

UGP COVER 2012 22/3/11 14:01 Page 2 THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH Undergraduate Prospectus Undergraduate 2012 Entry 2012 THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH Undergraduate Prospectus 2012 Entry www.ed.ac.uk EDINB E56 UGP COVER 2012 22/3/11 14:01 Page 3 UGP 2012 FRONT 22/3/11 14:03 Page 1 UGP 2012 FRONT 22/3/11 14:03 Page 2 THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH Welcome to the University of Edinburgh We’ve been influencing the world since 1583. We can help influence your future. Follow us on www.twitter.com/UniofEdinburgh or watch us on www.youtube.com/user/EdinburghUniversity UGP 2012 FRONT 22/3/11 14:03 Page 3 The University of Edinburgh Undergraduate Prospectus 2012 Entry Welcome www.ed.ac.uk 3 Welcome Welcome Contents Contents Why choose the University of Edinburgh?..... 4 Humanities & Our story.....................................................................5 An education for life....................................................6 Social Science Edinburgh College of Art.............................................8 pages 36–127 Learning resources...................................................... 9 Supporting you..........................................................10 Social life...................................................................12 Medicine & A city for adventure.................................................. 14 Veterinary Medicine Active life.................................................................. 16 Accommodation....................................................... 20 pages 128–143 Visiting the University............................................... -

Dundee Women's Trail Want to Know More?

Dundee Women’s Trail Many have made history worldwide. 21 Bella Keyzer 24 Janet Keiller Dundee Women’s Trail celebrates just a few amazing women whose lives touched 1922 - 1992 1737 - 1813 this city. Those we mark along this Trail are testimony to Dundee’s reputation for During World War Two, women took over She and her husband ran a cake and sweetie the jobs of the men who were fighting shop. One day, faced with a consignment of strong women. abroad, and Bella found her vocation as a unwanted bitter oranges, she boiled them welder in Caledon Shipyard. She was paid up to make the first chip marmalade. When The 25 women commemorated by bronze plaques in the city include artists, trades off four years later, but as soon as the Equal the menfolk died, she and her daughter- unionists, social reformers, suffragettes, a shipyard welder and a marine engineer. Opportunities Act was passed in 1975, she in-law Margaret ran the business - very was back. She was a loyal Labour Party successfully. member, and in 1992 Dundee District Take a walk through the streets they knew and glimpse the lives they led. Council, as it was then, gave her an award 25 Emma Caird (or Marryat) for promoting women’s equality. 1849 - 1927 Daughter of a mega-rich mill owner, she 22 Ethel Moorhead was a bright spark in her youth. In old 1869 - 1955 age, she was better known as ‘the greatest Ethel studied art in Paris and exhibited in benefactress Dundee has ever seen’, as she prestigious galleries. -

“COBBIE” and “THE KING of FORGUE” 1800S

THE MARQUIS OF HUNTLY, “COBBIE” AND “THE KING OF FORGUE” 1800s ames Allardes had inherited Boynsmill Estate in 1800, but by 1802 was living at J Cobairdy, where, although only the tenant of John Morison of Auchintoul, he lived very much the lifestyle of a laird and acquired the sobriquet of “Cobbie” as a result. One of his neighbouring landowners was the Duke of Gordon, and both men knew each other and had mutual dealings, especially when it came to improving the estate boundaries between lands at Kinnoir and Cobairdy. Aberdeen Journal 24 February 1802 The Duke’s son and heir, George, Marquis of Huntly at this time lived at Huntly Lodge, and oversaw the running of his father’s estates in the Huntly area, and became closely acquainted with James Allardes and also with Alexander Shand, in Conland. The outcome of these friendships was that these two prominent men of Forgue society were regular guests of the Marquis at his lavish parties. Detail of The Lodge and Castle from a drawing of Huntly 73 Huntly, Jan 19th 1802 sometime very unwell. If you like my Mr Editor, letter, I could send you an account of As you like Christmas gambols I am many gay scenes that took place during tempted to send you the annals of this the festivity of this noble party, among gay neighbourhood. Our Marquis of which were horse races of excellent Huntly, who is the adoration of all sport, on the race ground at the old ranks, assembled a large party by Castle of Huntly, by the Marquis, Lord sledges, &c. -

Edinburgh Suffragists: Exercising the Franchise at Local Level1

EDINBURGH SUFFRAGISTS: EXERCISING THE FRANCHISE AT LOCAL LEVEL1 Esther Breitenbach Key to principal women’s and political organisations ENSWS Edinburgh National Society for Women’s Suffrage ESEC Edinburgh Society for Equal Citizenship EWCA Edinburgh Women Citizens Association SFWSS Scottish Federation of Women’s Suffrage Societies WSPU Women’s Social and Political Union WFL Women’s Freedom League ILP Independent Labour Party SCWCA Scottish Council of Women Citizens Associations SWLF Scottish Women’s Liberal Federation NUSEC National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship ESU Edinburgh Social Union Introduction In the centenary year, the focus of commemoration was, of course, the parliamentary franchise. Yet this he year 2018 witnessed widespread celebrations was never the sole focus of suffrage campaigners’ Tacross the UK of the centenary of the partial activities. They sought to extend women’s rights in parliamentary enfranchisement of women in 1918. In many ways, through a variety of organisations and Scotland this meant ‘women 30 years or over who were campaigns, often inter-related and with overlapping themselves, or their husbands, occupiers as owners or memberships. Of particular importance were the tenants of lands or premises in their constituency in forms of franchise to which women were admitted which they claimed the vote’.2 A woman could also prior to 1918, and the ways in which women be registered if her husband was a local government responded to opportunities to vote and to seek public elector; the local government franchise in Scotland office at local level. This local activity should be was more stringent than the first criterion, and this franchise was therefore more restrictive than that seen, however, in the wider context of a suffrage which applied in England and Wales. -

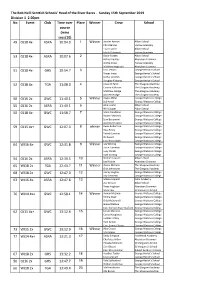

Div 1 Saturday

The Bob Neill Scottish Schools' Head of the River Races - Saturday 14th September 2019 Division 1 1.30pm No Event Club Time over Crew School course Place Winner (mins secs/10) 1 OJ18 4+ ASRA 10:58.2 Xander Beeson Albyn School OJ-18 4+ fastest Chris Bardas Harlaw Academy 1 Scott Lewis Mearns Academy crew Jakub Zbikowski Harlaw Academy Cox: Skye Balance Cults Academy 2 OJ18 4+ ASRA 11:16.0 Oscar Forbes Albyn School Ashley Geddes Aberdeen Grammar 2 Archie Innes Harlaw Academy Matthew Hughson Aberdeen Grammar Cox: Freya Hughson Aberdeen Grammar 3 OJ18 4+ GHS 12:24.4 Josh Jenkins George Heriot's School Fastest single Fraser Innes George Heriot's School 3 Archie Weetch George Heriot's School school OJ-18 4+ Douglas Richards George Heriot's School Cox: Olivia Brindle George Heriot's School 4 OJ18 4+ ASRA 12:27.6 Jan Barraclough Cults Academy Euan Fowler Albyn School 4 Gregor Charles Aberdeen Grammar Michel Dearsley Cults Academy Cox: Gabrielle Topp Kemnay Academy 6 OJ16 4+ ASRA 12:38.9 Alex Fowler Albyn School OJ-16 4+ fastest Will Cooper Albyn School 5 Joe Ritchie Aberdeen Grammar crew William Lawson Albyn School Cox: Harris Macdonald Albyn School 5 OJ18 4+ GWC 12:39.6 Rowen Marwick George Watsons College Sam Beaumont George Watsons College 6 Andrew Knowles George Watsons College Mark Freedman George Watsons College Cox: James Martin George Watsons College 8 WJ18 4+ ASRA 13:17.5 Abigail Topp Kemnay Academy W J-18 4+ Zoe Beeson Albyn School 7 Maisie Aspinall Cults Academy fastest crew Sophia Brew Cults Academy Cox: 9 WJ18 4+ GHS 13:44.0 Heather -

The Art of Picture Making 5 - 29 March 2014

(1926-1998) the art of picture making 5 - 29 march 2014 16 Dundas Street, Edinburgh EH3 6HZ tel 0131 558 1200 email [email protected] www.scottish-gallery.co.uk Cover: Paola, Owl and Doll, 1962, oil on canvas, 63 x 76 cms (Cat. No. 29) Left: Self Portrait, 1965, oil on canvas, 91.5 x 73 cms (Cat. No. 33) 2 | DAVID McCLURE THE ART OF PICTURE MAKING | 3 FOREWORD McClure had his first one-man show with The “The morose characteristics by which we Scottish Gallery in 1957 and the succeeding recognise ourselves… have no place in our decade saw regular exhibitions of his work. painting which is traditionally gay and life- He was included in the important surveys of enhancing.” Towards the end of his exhibiting contemporary Scottish art which began to life Teddy Gage reviewing his show of 1994 define The Edinburgh School throughout the celebrates his best qualities in the tradition 1960s, and culminated in his Edinburgh Festival of Gillies, Redpath and Maxwell but in show at The Gallery in 1969. But he was, even by particular admires the qualities of his recent 1957 (after a year painting in Florence and Sicily) Sutherland paintings: “the bays and inlets where in Dundee, alongside his great friend Alberto translucent seas flood over white shores.” We Morrocco, applying the rigour and inspiration can see McClure today, fifteen years or so after that made Duncan of Jordanstone a bastion his passing, as a distinctive figure that made a of painting. His friend George Mackie writing vital contribution in the mainstream of Scottish for the 1969 catalogue saw him working in a painting, as an individual with great gifts, continental tradition (as well as a “west coast intellect and curiosity about nature, people and Scot living on the east coast whose blood is part ideas. -

Hilary Mantel Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8gm8d1h No online items Hilary Mantel Papers Finding aid prepared by Natalie Russell, October 12, 2007 and Gayle Richardson, January 10, 2018. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © October 2007 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Hilary Mantel Papers mssMN 1-3264 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Hilary Mantel Papers Dates (inclusive): 1980-2016 Collection Number: mssMN 1-3264 Creator: Mantel, Hilary, 1952-. Extent: 11,305 pieces; 132 boxes. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The collection is comprised primarily of the manuscripts and correspondence of British novelist Hilary Mantel (1952-). Manuscripts include short stories, lectures, interviews, scripts, radio plays, articles and reviews, as well as various drafts and notes for Mantel's novels; also included: photographs, audio materials and ephemera. Language: English. Access Hilary Mantel’s diaries are sealed for her lifetime. The collection is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. -

SSMPC Scottish Schools Biathlon Championships

10/1/2019 htmlbi.htm SSMPC Scottish Schools Biathlon Championships Sep 29 2019 Biathlon Results P No Name Region Swim Run Total Under 10 Boys Harry Cook 1240 1261 1 52 Sc 2501 Lathallan School 0:37.02 2:52.740 Austin McCaul 1156 1177 2 62 Sc 2333 Robert Gordons College Junior School 0:39.82 2:58.310 Alex Cantley 1120 1078 3 49 Sc 2198 Drumoak Primary School 0:41.09 3:04.970 Oliver Hodzic 1072 1027 4 56 Sc 2099 Robert Gordons College 0:42.67 3:08.210 Alex Henthorn 568 1354 5 48 Sc 1922 Broomhill Primary School 0:59.55 2:46.420 Orson Murray 880 1039 6 59 Sc 1919 Robert Gordons College 0:49.09 3:07.460 Danny Pottinger 856 1024 7 46 Sc 1880 Airyhall Primary School 0:49.95 3:08.510 Maxwell Duncan 838 991 8 54 Sc 1829 Robert Gordons College 0:50.59 3:10.680 Saif Emad Elsayed 814 916 9 53 Sc 1730 Newtonhill Primary School 0:51.25 3:15.660 James Leask 934 601 10 58 Sc 1535 Robert Gordons College 0:47.23 3:36.670 Charlie Slane 1030 370 11 50 Sc 1400 Ferryhill Primary School 0:44.19 3:52.080 Jude Ritchie 658 718 12 60 Sc 1376 Robert Gordons College 0:56.59 3:28.840 George Milligan 940 433 13 63 Sc 1373 Unaffiliated 0:47.12 3:47.900 Nicholas Faber-Johnstone 658 643 14 55 Sc 1301 Robert Gordons College 0:56.42 3:33.890 Bruce Flett 724 469 15 51 Sc 1193 Kinellar Primary School 0:54.31 3:45.530 Aston Sharp 0 958 16 61 Sc 958 Robert Gordons College 1:21.54 3:12.800 Riyansh Kirodian 190 484 17 57 Sc 674 Robert Gordons College 1:12.09 3:44.470 Aran Reynolds 0 547 18 47 Sc 547 Braehead Primary School DNF 3:40.250 Under 10 Girls Ines De Kock 1078 1009 1 -

Notice of Situation of Polling Stations European Parliamentary Election Aberdeenshire Council Area Electoral Region of Scotland

NOTICE OF SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS EUROPEAN PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION ABERDEENSHIRE COUNCIL AREA ELECTORAL REGION OF SCOTLAND nd THURSDAY, 22 MAY, 2014 The number and situation of the polling stations to be used at the above election are as set out in the first and second columns respectively of the following table, and the description of the persons entitled to vote at each station is as set out in the third column of that table:- Number of Situation of Polling Station Description of Persons Polling entitled to vote thereat, Station being Electors resident in the undernoted Parliamentary Polling Districts: 1 Cairnie Public Hall WG1401 2 Glass Village Hall WG1402 3-5 Stewart’s Hall, Huntly WG1403 6 Drumblade School Nursery Building WG1404 7 Scott Hall, Forgue WG1405 8 Gartly Community Hall WG1406 9 Rhynie Community Education Centre WG1407 10 Rannes Public Hall, Kennethmont WG1408 11 Lumsden Village Hall WG1409 & WW1413 12 Tullynessle Hall WG1410 13 Keig Kirk WG1411 14 Monymusk Village Hall WG1412 15-16 Alford Community Centre WW1414 17 Craigievar Hall WW1415 18 Tough School WW1416 19 Corgarff Public Hall WW1501 20 Lonach Society Club Room, Bellabeg WW1502 21 Towie Public Hall WW1503 22 Braemar Village Hall WW1504 23 Crathie Church Hall WW1505 24 Albert and Victoria Halls, Ballater WW1506 25 Logie Coldstone Hall WW1507 26 MacRobert Memorial Hall, Tarland WW1508 27-28 Victory Hall, Aboyne WW1509 29 Lumphanan Village Hall WW1510 30 Learney Hall, Torphins WW 1511 31 Kincardine O’Neil Public Hall WW1601 Number of Situation of Polling Station -

'Scotland: Identity, Culture and Innovation'

Fulbright - Scotland Summer Institute ‘Scotland: Identity, Culture and Innovation’ University of Dundee University of Strathclyde, Glasgow 6 July-10 August 2013 Tay Rail Bridge, Dundee opened 13th July, 1887 The Clyde Arc, Glasgow opened 18th September, 2006 Welcome to Scotland Fàilte gu Alba We are delighted that you have come to Scotland to join the first Fulbright-Scotland Summer Institute. We would like to offer you the warmest of welcomes to the University of Dundee and the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow. Scotland is a fascinating country with a rich history and a modern and cosmopolitan outlook; we look forward to introducing you to our culture, identity and pioneering spirit of innovation. You will experience our great cities and the breathtaking scenery of the Scottish Highlands and we hope you enjoy your visit and feel inspired to return to Scotland in the future. Professor Pete Downes Principal and Vice-Chancellor, University of Dundee “Education and travel transforms lives and is central to our vision at the University of Dundee, which this year has been ranked one of the top ten universities in the UK for teaching and learning. We are delighted to bring young Americans to Dundee and to Scotland for the first Fulbright- Scotland Summer Institute to experience our international excellence and the richness and variety of our country and culture.” Professor Sir Jim McDonald Principal and Vice-Chancellor, University of Strathclyde “Strathclyde endorses the Fulbright objectives to promote leadership, learning and empathy between nations through educational exchange. The partnership between Dundee and Strathclyde, that has successfully attracted this programme, demonstrates the value of global outreach central to Scotland’s HE reputation. -

Cormack, Wade

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Sport and Physical Education in the Northern Mainland Burghs of Scotland c. 1600-1800 Cormack, Wade DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2016 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Sport and Physical Education in the Northern Mainland Burghs of Scotland c. -

Copy of Start Order (002)

The Bob Neill Scottish Schools' Head of the River Races - Sunday 15th September 2019 Division 1 2.00pm No Event Club Time over Place Winner Crew School course (mins secs/10) 49 OJ18 4x- ASRA 10:04.0 1 Winner Xander Beeson Albyn School Chris Bardas Harlaw Academy Euan Fowler Albyn School Jakub Zbikowski Harlaw Academy 53 OJ18 4x- ASRA 10:07.6 2 Oscar Forbes Albyn School Ashley Geddes Aberdeen Grammar Archie Innes Harlaw Academy Matthew Hughson Aberdeen Grammar 51 OJ18 4x- GHS 10:54.7 3 Josh Jenkins George Heriot's School Fraser Innes George Heriot's School Archie Weetch George Heriot's School Douglas Richards George Heriot's School 52 OJ18 4x- TGA 11:08.0 4 Ceasere Facio The Glasgow Academy Connor Kalkman The Glasgow Academy Matthew Hodge The Glasgow Academy Andrew Hodge The Glasgow Academy 58 OJ16 2x GWC 11:40.1 5 Winner Angus Millar George Watsons College Seb Ansell George Watsons College 55 OJ16 2x ASRA 11:49.1 6 Alex Fowler Albyn School Will Cooper Albyn School 50 OJ18 4x- GWC 11:58.7 7 Mark Freedman George Watsons College Rowen Marwick George Watsons College Sam Beaumont George Watsons College Andrew Knowles George Watsons College 59 OJ15 4x+ GWC 12:07.0 8 winner Ewan Robertson George Watsons College Ross Patey George Watsons College Patrick Lenihan George Watsons College Oli Sword George Watsons College Cox: Ross Adam George Watsons College 64 WJ16 4x- GWC 12:31.8 9 Winner Isla Wilding George Watsons College Rosie Cameron George Watsons College Lucy McGill George Watsons College Kate Skirving George Watsons College 54 OJ16 2x ASRA