Richard Pilbeam Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOWN the RABBIT HOLE and INTO the CURIOUS REALM of COSPLAY By

DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE AND INTO THE CURIOUS REALM OF COSPLAY by Margaret E. Haynes A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Anthropology Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Down the Rabbit Hole and into the Curious Realm of Cosplay A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Margaret E. Haynes Bachelor of Arts George Mason University, 2016 Director: Rashmi Sadana, Assistant Professor George Mason University Fall Semester 2018 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2017 Margaret E. Haynes All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION To my dog, Gypsy, who had to forgo hours of walks and playtime in order to supervise my writing. To my loving parents and younger brother, who are the foundation of my success with their unconditional support. To the cosplay community who welcomed me with open arms. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everyone who helped make this thesis possible! I would first like to give a huge thanks to my thesis advisor, Dr. Sadana, and the other members of my committee, Dr. Gatling and Dr. Schiller, who were always happy to give me constructive criticism on my ideas. A special thanks to the convention committees at Nekocon, Katsucon, and Anime Mid- Atlantic, who gave me permission to interview cosplayers at their conventions. This work would not have been possible without my friend, Samantha Ouellette, who introduced me to cosplay and conventions. -

24 Frames SF Tube Talk Reanimation in This Issue Movie News TV News & Previews Anime Reviews by Lee Whiteside by Lee Whiteside News & Reviews

Volume 12, Issue 4 August/September ConNotations 2002 The Bi-Monthly Science Fiction, Fantasy & Convention Newszine of the Central Arizona Speculative Fiction Society 24 Frames SF Tube Talk ReAnimation In This Issue Movie News TV News & Previews Anime Reviews By Lee Whiteside By Lee Whiteside News & Reviews The next couple of months is pretty slim This issue, we’ve got some summer ***** Sailor Moon Super S: SF Tube Talk 1 on genre movie releases. Look for success stories to talk about plus some Pegasus Collection II 24 Frames 1 Dreamworks to put Ice Age back in the more previews of new stuff coming this ***** Sherlock Hound Case File II ReAnimation 1 theatre with some extra footage in advance fall. **** Justice League FYI 2 of the home video release and Disney’s The big news of the summer so far is **** Batman: The Animated Series - Beauty & The Beast may show up in the success of The Dead Zone. Its debut The Legend Begins CASFS Business Report 2 regular theatre sometime this month. on USA Network on June 16th set **** ZOIDS : The Battle Begins Gamers Corner 3 September is a really dry genre month, with records for the debut of a cable series, **** ZOIDS: The High-Speed Battle ConClusion 4 only the action flick Ballistic: Eck Vs *** Power Rangers Time Force: Videophile 8 Sever on the schedules as of press time. Dawn Of Destiny Musty Tomes 15 *** Power Rangers Time Force: The End Of Time In Our Book (Book Reviews) 16 Sailor Moon Super S: Special Feature Pegasus Collection II Hary Potter and the Path to the DVD Pioneer, 140 mins, 13+ Secrets DVD $29.98 by Shane Shellenbarger 7 In Sailor Moon Super S, Hawkeye, Convention & Fandom Tigereye, and Fisheye tried to find Pegasus by looking into peoples dreams. -

Fortunato Cerlino, Michele Riondino Xiaoya Ma, Aniello Arena Con La Partecipazione Straordinaria Di Pippo Delbono E Stefania Sandrelli

MINERVA PICTURES GROUP FIGLI DEL BRONX e RAI CINEMA Presentano: regia di Toni D’Angelo con Fortunato Cerlino, Michele Riondino Xiaoya Ma, Aniello Arena con la partecipazione straordinaria di Pippo Delbono e Stefania Sandrelli una produzione MINERVA PICTURES FIGLI DEL BRONX con RAI CINEMA prodotto da GIANLUCA CURTI e GAETANO DI VAIO con il sostegno del MIBACT in associazione con ALIANTE e in associazione con ST ai sensi delle norme sul tax credit Distribuito in Italia da Via Ripamonti 89, Milano ufficio stampa: Studio PUNTOeVIRGOLA www.studiopuntoevirgola.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Falchi-Il-Film Twitter: #FALCHI CAST TECNICO Regia Toni D’Angelo Soggetto e sceneggiatura Giorgio Caruso, Toni D’Angelo, Marcello Olivieri Fotografia Rocco Marra Montaggio Marco Spoletini Musiche originali Nino D’Angelo Casting Marita D’Elia Scenografia Carmine Guarino Costumi Olivia Bellini Aiuto regia Andrea Vellucci Supervisione alla produzione Antonio Alessi, Angelo Zemella Organizzatore generale Fabio Lombardelli Direttore di produzione Francesco Di Sarno Produzione Minerva Pictures Group, Figli del Bronx con Rai Cinema Produttore esecutivo Minerva Pictures Group Distribuzione Koch Media Ufficio stampa Studio PUNTOeVIRGOLA Tel. 0639388909 [email protected] www.studiopuntoevirgola.com Durata 97’ CAST ARTISTICO Peppe Fortunato Cerlino Francesco Michele Riondino Mei Xiaoya Ma Ispettore Russo Aniello Arena e con la partecipazione straordinaria di Pippo Delbono nel ruolo di Marino e con la partecipazione straordinaria di Stefania Sandrelli nel ruolo di Arianna Luciano Gaetano Amato Liu Alessandra Cao Agente Caserta Carlo Caracciolo Giovane ragazza bionda Noemi Maria Conigni Arturo Cavasino Oscar di Maio Hwang Hong Guo Long Vincenzo Giovane Latitante Carmine Monaco Agente Migliaccio Carmine Paternoster Agente De Nicola Massimiliano Rossi Tuccillo Latitante Salvatore Striano Chen Ruichi Xu Nel corso della lavorazione del film non sono stati inflitti maltrattamenti di alcun genere agli animali. -

Investigating the Freedom of Gender Performativity Within the Queer Space of Cosplay/Cross Play

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@USM 3rd KANITA POSTGRADUATE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON GENDER STUDIES 16 – 17 November 2016 Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang To be or not to be the queerest of them all: Investigating the Freedom of Gender Performativity within the Queer Space of Cosplay/Cross play Elween Loke Malaysia Corresponding Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper examines freedom of gender performativity among Crossplayers and Cosplayers within the queer space in which they embody gendered identities. Cosplay refers to acts of role- playing based on characters from anime and manga, or Japanese animation and comic respectively. Crossplay, on the other hand, is similar to Cosplay, except that participants dressed up as characters that are of their opposite gender. While Cosplay is already regarded as a queer activity, Crossplay is observed as the queerest among the queer, as it defies the traditional gender norms in patriarchal country like Malaysia. This research is significant as both Malaysian Cosplay subculture (and Crossplay), which is increasingly popular, remained understudied, as well as issues with regard to the deviant aspect of gender performativity. Using data collected from in-depth interviews with eight respondents and four sessions of participant observation at various Cosplay events, the researcher observed interactions between Crossplayers and Cosplayers, and subsequently analysed the findings to provide insights into freedom of gender performativity within the queer space. Findings and analyses showed that, while the queer space provides a space for participants to construct their very own gender identity, it is not independent of the influence of the traditional gender dichotomy. -

Discover Our Complete Catalogue, Click Here!

2 TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW FILMS 4 IN PRODUCTION 42 LIBRARY 48 RESTORED MASTERPIECES 54 SPAGHETTI WESTERN 66 ACTION 70 HORROR/SCI-FI 76 ADVENTURE 82 DRAMA 86 COMEDY 90 EROTIC 94 CONTACTS 101 3 4 NEW FILMS 5 Directed by Alessio Liguori Cast: Andrei Claude (Game of Thrones), David Keynes (Pirates of the Carribean), Jack Kane (Dragonheart Vengeance / The A List), Zak Sutcliffe, Sophie Jane Oliver, Terence Anderson Year of Production: 2019 Country: Italy, Germany (English spoken) Genre: Mistery, Fantasy, Coming of Age Duration: 76’ 6 SHORTCUT A group of five teenagers is trapped inside their school bus after a mysterious creature invade the road. Time runs and every passing minute decreases their survival chances against the constant threats of that unknown entity. 7 Directed by Marco Coppola Cast: Charlie Hofheimer (24: Legacy /Mad Men / Black Hawk Down), Leticia Peres, Natalia Dyer (Stranger Things) Year of Production: 2019 Country: USA Genre: Romance, Drama, Comedy Duration: 80’ 8 THE NEAREST HUMAN BEING Devin's struggles between an office job he hates and a pitiful career as an actor. Things get worse when his beautiful girlfriend Jasmine decides to stop hoping he could ever turn into serious 'relationship material'. She seizes the opportunity to try new experiences but soon her reckless single life induces Jasmine to question herself. Will she give Devin a second chance? 9 Directed by Simone Isola and Fausto Trombetta Original Title: Se c'è un Aldilà sono Fottuto. Vita e Cinema di Claudio Caligari Cast: Claudio Caligari, Alessandro Borghi (Romolus & Remus - The First King / On my Skin / Naples in Veils / Suburra), Valerio Mastandrea (Euforia / Perfect Strangers / Pasolini), Luca Marinelli (They call me Jeeg / Don’t be Bad / Martin Eden) Year of production: 2019 Country: Italy Genre: Documentary Duration: 104' 10 NO FILTERS. -

1 Undoing Gender Through Performing The

1 Undoing Gender through Performing the Other Anastasia Seregina1 1Anastasia Seregina ([email protected]) is a Lecturer in Marketing at Goldsmiths, University of London, Lewisham Way, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, United Kingdom. 2 Abstract Following the perspective on gender as a socially constructed performance, consumer research has given light to how individuals take on, negotiate, and express a variety of gender roles. Yet the focus of research has remained on gender roles themselves, largely overlooking the underlying process of gender performativity and consumers’ engagement with it in the context of their everyday lives. Set within a performance methodology and the context of crossplay in live action role-playing games, this paper explores how individuals undo gender on a subjective level, thus becoming conscious and reflexive of gender performativity. The study suggests that individuals become active in undoing gender through engaging in direct, bodily performance of the gender other. Such performance does not challenge or ridicule norms, but pushes individuals to actively figure out for themselves how gender is performed. As a result, individuals become aware of gender performativity and become capable of actively recombining everyday performance. Keywords: gender performativity, performance, agency, crossplay, live action role-playing game, LARP 3 Introduction Gender is a central aspect of how we define ourselves and how those around us define us. Within contemporary consumer culture, gender also becomes inseparable from consumption, its practices, objects, and contexts (Schroeder and Zwick 2004; Holt and Thompson 2004). Butler (1990, 2004) proposed that gender is a performatively produced doing, that is, it is a doing based in a repetition that creates its own effect. -

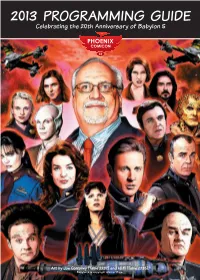

2013 PROGRAMMING GUIDE Celebrating the 20Th Anniversary of Babylon 5

2013 PROGRAMMING GUIDE Celebrating the 20th Anniversary of Babylon 5 Art by Joe Corroney (Table 2237) and Hi Fi (Table 2235). Babylon 5 is copyright Warner Bros. 2 PHOENIX COMICON 2013 • PROGRAMMING GUIDE • PHOENIXCOMICON.COM PHOENIX COMICON 2013 • PROGRAMMING GUIDE • PHOENIXCOMICON.COM 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Hyatt Regency Map .....................................................6 Renaissance Map ...........................................................7 Exhibitor Hall Map .................................................. 8–9 Programming Rooms ........................................... 10–11 Phoenix Comicon Convention Policies .............12 Exhibitor & Artist Alley Locations .............14-15 Welcome to Phoenix Comicon, Guest Locations...........................................................16 Guest Bios .............................................................. 18–22 the signature pop-culture event of Programming Schedule ................................. 24–35 the southwest! Gaming Schedule ..............................................36–42 If you are new to us, or have never been to a “comicon” before, we welcome you. Programming Descriptions.........................44–70 This weekend is the culmination of efforts by over seven hundred volunteers over the past twelve months all with a singular vision of putting on the most fun convention you’ll attend. Festivities kick off Thursday afternoon and continue throughout the weekend. Spend the day checking out the exhibitor hall, meeting actors and writers, buying that hard to -

Gender, Sexuality, and Cosplay: a Case Study of Male-To-Female Crossplay

Gender, Sexuality, and Cosplay: A Case Study of Male-to-Female Crossplay The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation “Gender, Sexuality, and Cosplay: A Case Study of Male-to-Female Crossplay,” The Phoenix Papers: First Edition, (Apr 2013), 89-110. ISSN: 2325-2316. Published Version http://fansconf.a-kon.com/dRuZ33A/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/ Gender-Sexuality-and-Cosplay-by-Rachel-Leng1.pdf;http:// fansconf.a-kon.com/dRuZ33A/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Gender- Sexuality-and-Cosplay-by-Rachel-Leng1.pdf Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:13481274 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Gender, Sexuality, and Cosplay: A Case Study of Male-to-Female Crossplay Rachel Leng "Let's get one thing straight. I am not gay. I like girls a lot. That‟s why most of my favorite anime characters are girls. I like them so much that I sometimes dress up like them." Tenshi, Crossplay.net, quoted on “Why Crossplay?” forum,(May 2012). “Good crossplay reveals the pure love for an anime character […] that is at the heart of all cosplay, regardless of the gender of [the] cosplayer or the character being cosplayed. In my perspective, it takes a real man to dress like a 10-year-old girl.” Lyn, Cosplay.com, quoted on “Views on Crossplay” thread (Oct. -

Superheroes & Stereotypes: a Critical Analysis of Race, Gender, And

SUPERHEROES & STEREOTYPES: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF RACE, GENDER, AND SOCIAL ISSUES WITHIN COMIC BOOK MATERIAL Gabriel Arnoldo Cruz A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2018 Committee: Alberto González, Advisor Eric Worch Graduate Faculty Representative Joshua Atkinson Frederick Busselle Christina Knopf © 2018 Gabriel Arnoldo Cruz All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Alberto González, Advisor The popularity of modern comic books has fluctuated since their creation and mass production in the early 20th century, experiencing periods of growth as well as decline. While commercial success is not always consistent from one decade to the next it is clear that the medium has been and will continue to be a cultural staple in the society of the United States. I have selected this type of popular culture for analysis precisely because of the longevity of the medium and the recent commercial success of film and television adaptations of comic book material. In this project I apply a Critical lens to selected comic book materials and apply Critical theories related to race, class, and gender in order to understand how the materials function as vehicles for ideological messages. For the project I selected five Marvel comic book characters and examined materials featuring those characters in the form of comic books, film, and television adaptations. The selected characters are Steve Rogers/Captain America, Luke Cage, Miles Morales/Spider-Man, Jean Grey, and Raven Darkholme/Mystique. Methodologically I interrogated the selected texts through the application of visual and narrative rhetorical criticism. -

Abstract the Gendered Superhero

i ABSTRACT THE GENDERED SUPERHERO: AN EXAMINATION OF MASCULINITIES AND FEMININITIES IN MODERN AGE DC AND MARVEL COMIC BOOKS Jennifer Volintine, M.A. Department of Anthropology Northern Illinois University, 2016 Kendall M. Thu, Director This thesis examines American gender concepts of masculinity and femininity depicted in six Modern Age superhero comic books. Specifically, it examines how the American gender concepts of hegemonic masculinity, hypersexualized masculinity, emphasized femininity, and hypersexualized femininity are depicted in three Marvel and three DC comic books. This examination found that despite gender differences defined by biological essentialism that legitimates gender inequality, female and male superheroes are much more alike than different through what I term ―visionary gender.‖ Also, it examines indicators of gender not previously examined in American superhero comic books. In particular, it examines the text of superhero comic books to demonstrate that language use in comic books is gendered and that female superheroes use interruption as a way to control and dominate male superheroes in conversation. In addition, two viewpoints within the comic book subculture are examined: the comic book readers and the comic book artists. It addresses the readers‘ interpretation of gender depicted in a selection of images illustrating superhero characters‘ bodies and it observes the artists‘ intention in illustrating superhero characters with respect to gender. i NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DE KALB, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 THE GENDERED SUPERHERO: AN EXAMINATION OF MASCULINITIES AND FEMININITIES IN MODERN AGE DC AND MARVEL COMIC BOOKS BY JENNIFER VOLINTINE ©2016 Jennifer Volintine A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY Thesis Director: Kendall M. -

Generating Natural Language Adversarial Examples (Supplementary Material)

Generating Natural Language Adversarial Examples (Supplementary Material) Moustafa Alzantot1∗, Yash Sharma2∗, Ahmed Elgohary3, Bo-Jhang Ho1, Mani B. Srivastava1, Kai-Wei Chang1 1Department of Computer Science, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) fmalzantot, bojhang, mbs, [email protected] 2Cooper Union [email protected] 3Computer Science Department, University of Maryland [email protected] 1 Additional Sentiment Analysis Results On the following page(s), Table1 shows an ad- ditional set of attack results against the sentiment analysis model described in our paper. 2 Additional Textual Entailment Results On the following page(s), Table2 shows an addi- tional set of attack results against the textual en- tailment model described in our paper. Moustafa∗ Alzantot and Yash Sharma contribute equally to this work. Original Text Prediction = Positive. (Confidence = 78%) The promise of Martin Donovan playing Jesus was, quite honestly, enough to get me to see the film. Definitely worthwhile; clever and funny without overdoing it. The low quality filming was probably an appropriate effect but ended up being a little too jarring, and the ending sounded more like a PBS program than Hartley. Still, too many memorable lines and great moments for me to judge it harshly. Adversarial Text Prediction = Negative. (Confidence = 59.9%) The promise of Martin Donovan playing Jesus was, utterly frankly, enough to get me to see the film. Definitely worthwhile; clever and funny without overdoing it. The low quality filming was presumably an appropriate effect but ended up being a little too jarring, and the ending sounded more like a PBS program than Hartley. Still, too many memorable lines and great moments for me to judge it harshly. -

Newsletter 07/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 07/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 330 - Juli 2013 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 07/13 (Nr. 330) Juli 2013 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, ben: die Videoproduktion. Da es sich ge zu verzeichnen. Da wäre zum Einen liebe Filmfreunde! dabei um eine extrem zeitaufwändige eine weitere Filmpremiere, die wir Angelegenheit handelt und der Tag videotechnisch festgehalten haben: Bestimmt ist es Ihnen als fleißigem Le- nach wie vor nur 24 Stunden hat, müs- EIN FREITAG IN BARCELONA. Zum ser unseres Newsletters schon längst sen wir mit der uns zur Verfügung ste- Anderen haben wir zwei Videos hoch- aufgefallen, dass wir ganz still und henden Zeit haushalten. Nachteile ent- geladen, die bereits 2011 während des heimlich dessen Erscheinungsfrequenz stehen Ihnen dadurch in keiner Weise. Widescreen Weekends in Bradford ent- geändert haben. Waren Sie es bislang Denn unseren Service in Bezug auf standen sind: TONY EARNSHAW IN gewohnt, alle 14 Tage eine neue Aus- DVDs und Blu-rays halten wir weiter- CONVERSATION WITH CLAIRE gabe in Händen zu halten oder auf Ih- hin mit höchster Priorität aufrecht. Da BLOOM und JOE DUNTON rem Bildschirm zu lesen, so passiert sich in den letzten Jahren nun doch INTRODUCING DANCE CRAZE IN dies seit diesem Jahr nunmehr erst alle einige Monatsmagazine in Deutschland 70MM. Zusätzlich haben wir noch eine vier Wochen. Aber keine Sorge: was etabliert haben, deren Hauptaugenmerk Kurzversion unseres BROKEN die enthaltenen Informationen angeht, den Heimmedien gilt und die an fast CIRCLE Videos erstellt, das weitere so hat sich daran nichts geändert.