DOWN the RABBIT HOLE and INTO the CURIOUS REALM of COSPLAY By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Icg Newsletter

THE ICG NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED BY THE INTERNATIONAL COSTUMERS' GUILD, INC. A 501(C)(3) NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION VOLUME VIII, ISSUE 5 - SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2009 The International Costumers' Guild, Inc. (ICG), is an affiliation of amateur, hobbyist, and professional costumers dedicated to the promotion and education of costuming as an art form in all its aspects. The awards from the Masquerade Judges followed: FROM THE WORLDCON: Novice Division-Presentation: By Patrick J. and Leah R. O’Connor (CCG) Best in Class: Jennifer Aubin for “X-Men-The Phoenix” Best Character: Colin Betts for “Green Lantern” This year’s World Science-Fiction Convention (Anticipation 2009) Recreation: Jennifer Wynne for “Wanted: One Hero” was in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The Masquerade was chaired by photo by Christine Mak, pxlbarrel Byron Connell . Novice Division- Like Neil Armstrong, we came on behalf of all mankind, but Workmanship: particularly the Chicagoland Chapter, with the ancillary goal of Best in Class: Jennifer delivering the coveted(?) Cement Overshoes Award to a suitable Wynne for “Wanted: One contestant in the Masquerade, and of course, to report back to the Hero” – also noted for Membership on the outcome of that competition. “best use of spandex.” The Masquerade took place at the Palais de Congres de Montreal There is “Well Tailored,” on the evening of Saturday, August 8, 2009. “Really Well-tailored,” and 23 groups competed for awards; the entries were of such high “Looks Like it was Painted quality that the judges could not decide on an overall Best in Show, on” Jennifer W’s costume and none was awarded. This was not due to any lack of excellence— was in the third category.. -

Protoculture Addicts #61

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ PROTOCULTURE ✾ PRESENTATION ........................................................................................................... 4 STAFF WHAT'S GOING ON? ANIME & MANGA NEWS .......................................................................................................... 5 Claude J. Pelletier [CJP] — Publisher / Manager VIDEO & MANGA RELEASES ................................................................................................... 6 Martin Ouellette [MO] — Editor-in-Chief PRODUCTS RELEASES .............................................................................................................. 8 Miyako Matsuda [MM] — Editor / Translator NEW RELEASES ..................................................................................................................... 10 MODEL NEWS ...................................................................................................................... 47 Contributors Aaron Dawe Kevin Lilliard, James S. Taylor REVIEWS Layout LIVE-ACTION ........................................................................................................................ 15 MODELS .............................................................................................................................. 46 The Safe House MANGA .............................................................................................................................. 54 Cover PA PICKS ............................................................................................................................ -

Orlando in 2015

Fannish Inquisition Survey: Orlando Worldcon Bid Worldcon Bid: Orlando What are the proposed dates for which you are bidding? September 2nd-6th, 2015 (Labor Day weekend) What is your proposed convention host city? Is your convention site in a city center location or a suburb? If a suburb, what are the transport options into the city center? How far is the site from the city center? We are bidding Orlando, Florida, specifically Walt Disney World. It is located about a twenty-minute drive from downtown Orlando. Walt Disney World connects to the LYNX Central Florida Transportation Authority at both the Transportation and Ticket Center and the Downtown Disney Entertainment Complex, and provides free bus service from your hotel to either location. By 2014, SunRail, Orlando’s new light rail service, will run north-south and through downtown Orlando. Walt Disney World will provide free shuttle service to and from the nearest SunRail station in Kissimmee. What is the typical current airfare to your closest airport from world cities such as London, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, Melbourne? Atlanta? (April 2013): According to kayak.com - to Orlando from London: $541, from Boston: $114, from Chicago: $142, from LA: $134, from Melbourne: $1,788, from Atlanta: $118. Do international flights, as well as domestic, fly into your local airport? Which airlines? If not, where is the closest international airport? Are direct flights from the cities above flown into your local airport? Orlando is a world destination. Over one hundred different domestic and international flights regularly fly to Orlando, including many nonstop international flights. -

Investigating the Freedom of Gender Performativity Within the Queer Space of Cosplay/Cross Play

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@USM 3rd KANITA POSTGRADUATE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON GENDER STUDIES 16 – 17 November 2016 Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang To be or not to be the queerest of them all: Investigating the Freedom of Gender Performativity within the Queer Space of Cosplay/Cross play Elween Loke Malaysia Corresponding Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper examines freedom of gender performativity among Crossplayers and Cosplayers within the queer space in which they embody gendered identities. Cosplay refers to acts of role- playing based on characters from anime and manga, or Japanese animation and comic respectively. Crossplay, on the other hand, is similar to Cosplay, except that participants dressed up as characters that are of their opposite gender. While Cosplay is already regarded as a queer activity, Crossplay is observed as the queerest among the queer, as it defies the traditional gender norms in patriarchal country like Malaysia. This research is significant as both Malaysian Cosplay subculture (and Crossplay), which is increasingly popular, remained understudied, as well as issues with regard to the deviant aspect of gender performativity. Using data collected from in-depth interviews with eight respondents and four sessions of participant observation at various Cosplay events, the researcher observed interactions between Crossplayers and Cosplayers, and subsequently analysed the findings to provide insights into freedom of gender performativity within the queer space. Findings and analyses showed that, while the queer space provides a space for participants to construct their very own gender identity, it is not independent of the influence of the traditional gender dichotomy. -

SFC Update Vol. 1 No. 17

SoUTheRN FANDOM CONFEDeRATiON UPDATE VoLUMe 1, NuMBeR 17 JAnUaRY 2011 2 3 Editorial Apology: It’s been too long. I’d meant to get back to the monthly publishing schedule once ReConStruction was through. I even made a go at it, getting out an issue (sloppily thrown together, but complete enough), and doing most of the work towards another one. Exhaustion set in, and the half-issue I had fell by the wayside. Then I went through a breakup, and didn’t much feel like working on zines (somewhere in this period, my membership in SFPA lapsed, for real this time – I hope to make a return in time for the 50 th anniversary). Now, it’s a new year, and I’m ready to make a go at it again. This issue is nearly complete, and it’s my traditional day for wrapping it – the first Thursday of the month. I’ve been working with some local fans on starting an annual con here in Raleigh, and we should have something substantial to announce on that shortly. I’m still fairly involved in other folks’ cons, though I’m not going to chair one again for a while. In case anyone was wondering but hadn’t heard, the NASFiC did better than break-even, so once we’ve got all of the bills wrapped up, we’ll do a partial reimbursement for staff, volunteers, and program participants. The cover this issue is once again from Jose Sanchez, who’s provided an absolute wealth of pieces, so I’m running some as interiors, too. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript and are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was scanned as received. Pages 25-27, and 66 This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Cybercultures from the East: Japanese Rock Music Fans in North America By An Nguyen, B.A. A thesis submitted to The Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Sociology and Anthropology Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario April 2007 © An Nguyen 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-26963-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-26963-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. -

Orlando for 2026

Questionnaire Instructions The questionnaire below includes some of the most asked questions for Worldcon/SMOFcons and bids. Please email the completed answers to [email protected] by Sunday, 22 November, 2020. The completed questionnaires will be posted on the Smofcon 37 ¼ website (https://sites.grenadine.co/sites/conzealand/en/smofcon-37-14) by Tuesday, 1 December, 2020. Please answer all the questions in line below. If a question doesn’t apply to your bid, please state: N/A. If the answer won’t be known until some future date, please provide an estimate of when you will be able to provide an answer. For example, for the question about room rates you might answer “These are expected to be agreed by [date]. Current internet rates are X per night room only for a double or twin and Y for single occupancy.” QUESTIONNAIRE General Name of Bid Orlando 2026 What dates are you bidding for? We’re looking at early to mid-August 2026. We will not be choosing the American Labor Day weekend of early September. What is your proposed convention host city? Is your convention site in a city center location or a suburb? If a suburb, what are the transport options into the city centre? How far is the site from the city centre? Orlando, FL. We’ve not determined our site yet, so we cannot speak to transport options. However, Orlando does have passenger rail (SunRail) and high-speed rail (Brightline) currently being expanded, both of which will connect Orlando International Airport to various points in Orlando at or near possible convention sites well before 2026. -

1 Undoing Gender Through Performing The

1 Undoing Gender through Performing the Other Anastasia Seregina1 1Anastasia Seregina ([email protected]) is a Lecturer in Marketing at Goldsmiths, University of London, Lewisham Way, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, United Kingdom. 2 Abstract Following the perspective on gender as a socially constructed performance, consumer research has given light to how individuals take on, negotiate, and express a variety of gender roles. Yet the focus of research has remained on gender roles themselves, largely overlooking the underlying process of gender performativity and consumers’ engagement with it in the context of their everyday lives. Set within a performance methodology and the context of crossplay in live action role-playing games, this paper explores how individuals undo gender on a subjective level, thus becoming conscious and reflexive of gender performativity. The study suggests that individuals become active in undoing gender through engaging in direct, bodily performance of the gender other. Such performance does not challenge or ridicule norms, but pushes individuals to actively figure out for themselves how gender is performed. As a result, individuals become aware of gender performativity and become capable of actively recombining everyday performance. Keywords: gender performativity, performance, agency, crossplay, live action role-playing game, LARP 3 Introduction Gender is a central aspect of how we define ourselves and how those around us define us. Within contemporary consumer culture, gender also becomes inseparable from consumption, its practices, objects, and contexts (Schroeder and Zwick 2004; Holt and Thompson 2004). Butler (1990, 2004) proposed that gender is a performatively produced doing, that is, it is a doing based in a repetition that creates its own effect. -

Jason Grossman [email protected] · 16 Bellingham Drive, Kendall Park, NJ 08824 · 848-250-6497

Jason Grossman [email protected] · 16 Bellingham Drive, Kendall Park, NJ 08824 · 848-250-6497 EDUCATION The School of Visual Arts, New York, NY Bachelor of Fine Arts in Illustration, June 2011 Activities: Orientation Leader Illustration Department Tour Guide Disability Services Mentor CREATIVE SKILLS Digital Media: Adobe Creative Suite (Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign, Flash, Dreamweaver, Bridge) Unity Maya Traditional Media: Acrylics Watercolors Inking PORTFOLIO: jlgart.daportfolio.com https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCpi0dxOuVhF1CRUnNLG0IiA PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE JLG Illustration, Metuchen, NJ Freelance Illustrator May 2009 - Present • Piloted concepts as the sole freelance illustrator (including original and commissioned artwork) • Designed & implemented marketing, promotion, and sales plans at art exhibitions as well as large video game and comics conventions (see list below) • Analyzed & computed all financial items related • Contacting clients for commissions & rendered ideas into artwork Brookstone, Inc., Edison, NJ Sales Associate November 2011 - Present • Communicated & served customers directly on the sales floor • Calculated & performed transactions • Performing live demonstrations & instruction for customers • Organizing & handling incoming stock ART EXHIBITIONS School of Visual Arts: Final Exhibition School of Visual Arts: Classical Myths – Transformed Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art Convention Metuchen Art Works: Group Show New York Comic Con Rhode Island Comic Con Anime Next Zenkaikon Katsucon C2E2 Magfest Castle Point Anime Boston New York Anime Festival Dexcon Too Many Games Expo Youmacon AnimeUSA Anime North Otakon Awsomecon Atlantic City Comic Con INTERESTS: Magic: The Gathering, Sci Fi/Fantasy, Video Games . -

The Perfect Victim: the “Profile in DERP” Farce

The Perfect Victim: The “Profile in DERP” Farce Our findings and conclusions of our investigation into the intentional false public banning of Jkid from /cgl/, the misconduct and social bullying of Jkid by the 4chan moderators and their friends involved during and after Otakon 2010, and the real problem behind the scenes of 4chan.org By a concerned group of 4channers. Twitter: @Themuckrakers Formspring: www.formspringme/Themuckrakers Youtube: youtube.com/user/Themuckraker4 Email: [email protected] 1. Obligatory Inb4 to prevent potential apathic thoughts 2. Introduction 3. Summary of Investigation 4. Details of Investigation 5. Conclusions and what you can do. Appendix: - The Underworld Logs - The Snacks AIM Notes Inb4 the following: Not your personal army Who cares? Who gives a shit/fuck? I don‟t care lol autism lol assburgers lol bullying lol black retard lol retard lol Jkid DEAL WITH IT why didn‟t he manned up U MAD why didn‟t he be a man lol aspergers I don‟t give a fuck MODS=GODS Why didn‟t he kill himself? This isn‟t my problem That‟s old history That‟s ancient history Not my problem Why are you ressurrecting I don‟t give a damn I don‟t give a fuck No spergin it No jerking it Lol black aspie MAN UP Why can‟t he get out more Whites Only No blacks allowed No asspies/aspies/spergs allowed Why can‟t he go to cosplay.com/ flickr/picasa/cosplaylab.com like everyone else? Bitch about mods somewhere else Emo bitch Get the fuck over it Why are you making a big deal out of it? You making a big deal out of nothing. -

Conventional Protections for Commercial Fan Art Under the U.S. Copyright Act

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 31 XXXI Number 2 Article 4 2021 Conventional Protections for Commercial Fan Art Under the U.S. Copyright Act Rachel Morgan Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Rachel Morgan, Conventional Protections for Commercial Fan Art Under the U.S. Copyright Act, 31 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 514 (2021). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol31/iss2/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Conventional Protections for Commercial Fan Art Under the U.S. Copyright Act Cover Page Footnote Rachel Morgan is a third-year student at Fordham University School of Law and a Senior Notes and Articles Editor for the Intellectual Property, Media, and Entertainment Law Journal. Prior to law school, she attended Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania where she majored in History and Italian Studies. She wrote this Note as an independent study in the spring of her second year. The author would like to thank Professor Courtney Cox for her guidance and supervision throughout the Note-writing process, as well as her fellow Executive Board members on the journal for their help in editing and publishing this Note. -

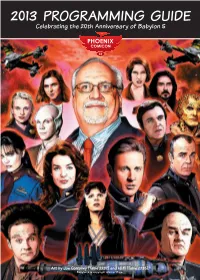

2013 PROGRAMMING GUIDE Celebrating the 20Th Anniversary of Babylon 5

2013 PROGRAMMING GUIDE Celebrating the 20th Anniversary of Babylon 5 Art by Joe Corroney (Table 2237) and Hi Fi (Table 2235). Babylon 5 is copyright Warner Bros. 2 PHOENIX COMICON 2013 • PROGRAMMING GUIDE • PHOENIXCOMICON.COM PHOENIX COMICON 2013 • PROGRAMMING GUIDE • PHOENIXCOMICON.COM 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Hyatt Regency Map .....................................................6 Renaissance Map ...........................................................7 Exhibitor Hall Map .................................................. 8–9 Programming Rooms ........................................... 10–11 Phoenix Comicon Convention Policies .............12 Exhibitor & Artist Alley Locations .............14-15 Welcome to Phoenix Comicon, Guest Locations...........................................................16 Guest Bios .............................................................. 18–22 the signature pop-culture event of Programming Schedule ................................. 24–35 the southwest! Gaming Schedule ..............................................36–42 If you are new to us, or have never been to a “comicon” before, we welcome you. Programming Descriptions.........................44–70 This weekend is the culmination of efforts by over seven hundred volunteers over the past twelve months all with a singular vision of putting on the most fun convention you’ll attend. Festivities kick off Thursday afternoon and continue throughout the weekend. Spend the day checking out the exhibitor hall, meeting actors and writers, buying that hard to