Investigating the Freedom of Gender Performativity Within the Queer Space of Cosplay/Cross Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOWN the RABBIT HOLE and INTO the CURIOUS REALM of COSPLAY By

DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE AND INTO THE CURIOUS REALM OF COSPLAY by Margaret E. Haynes A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Anthropology Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Down the Rabbit Hole and into the Curious Realm of Cosplay A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Margaret E. Haynes Bachelor of Arts George Mason University, 2016 Director: Rashmi Sadana, Assistant Professor George Mason University Fall Semester 2018 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2017 Margaret E. Haynes All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION To my dog, Gypsy, who had to forgo hours of walks and playtime in order to supervise my writing. To my loving parents and younger brother, who are the foundation of my success with their unconditional support. To the cosplay community who welcomed me with open arms. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everyone who helped make this thesis possible! I would first like to give a huge thanks to my thesis advisor, Dr. Sadana, and the other members of my committee, Dr. Gatling and Dr. Schiller, who were always happy to give me constructive criticism on my ideas. A special thanks to the convention committees at Nekocon, Katsucon, and Anime Mid- Atlantic, who gave me permission to interview cosplayers at their conventions. This work would not have been possible without my friend, Samantha Ouellette, who introduced me to cosplay and conventions. -

1 Undoing Gender Through Performing The

1 Undoing Gender through Performing the Other Anastasia Seregina1 1Anastasia Seregina ([email protected]) is a Lecturer in Marketing at Goldsmiths, University of London, Lewisham Way, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, United Kingdom. 2 Abstract Following the perspective on gender as a socially constructed performance, consumer research has given light to how individuals take on, negotiate, and express a variety of gender roles. Yet the focus of research has remained on gender roles themselves, largely overlooking the underlying process of gender performativity and consumers’ engagement with it in the context of their everyday lives. Set within a performance methodology and the context of crossplay in live action role-playing games, this paper explores how individuals undo gender on a subjective level, thus becoming conscious and reflexive of gender performativity. The study suggests that individuals become active in undoing gender through engaging in direct, bodily performance of the gender other. Such performance does not challenge or ridicule norms, but pushes individuals to actively figure out for themselves how gender is performed. As a result, individuals become aware of gender performativity and become capable of actively recombining everyday performance. Keywords: gender performativity, performance, agency, crossplay, live action role-playing game, LARP 3 Introduction Gender is a central aspect of how we define ourselves and how those around us define us. Within contemporary consumer culture, gender also becomes inseparable from consumption, its practices, objects, and contexts (Schroeder and Zwick 2004; Holt and Thompson 2004). Butler (1990, 2004) proposed that gender is a performatively produced doing, that is, it is a doing based in a repetition that creates its own effect. -

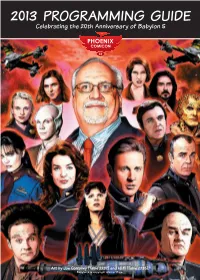

2013 PROGRAMMING GUIDE Celebrating the 20Th Anniversary of Babylon 5

2013 PROGRAMMING GUIDE Celebrating the 20th Anniversary of Babylon 5 Art by Joe Corroney (Table 2237) and Hi Fi (Table 2235). Babylon 5 is copyright Warner Bros. 2 PHOENIX COMICON 2013 • PROGRAMMING GUIDE • PHOENIXCOMICON.COM PHOENIX COMICON 2013 • PROGRAMMING GUIDE • PHOENIXCOMICON.COM 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Hyatt Regency Map .....................................................6 Renaissance Map ...........................................................7 Exhibitor Hall Map .................................................. 8–9 Programming Rooms ........................................... 10–11 Phoenix Comicon Convention Policies .............12 Exhibitor & Artist Alley Locations .............14-15 Welcome to Phoenix Comicon, Guest Locations...........................................................16 Guest Bios .............................................................. 18–22 the signature pop-culture event of Programming Schedule ................................. 24–35 the southwest! Gaming Schedule ..............................................36–42 If you are new to us, or have never been to a “comicon” before, we welcome you. Programming Descriptions.........................44–70 This weekend is the culmination of efforts by over seven hundred volunteers over the past twelve months all with a singular vision of putting on the most fun convention you’ll attend. Festivities kick off Thursday afternoon and continue throughout the weekend. Spend the day checking out the exhibitor hall, meeting actors and writers, buying that hard to -

Gender, Sexuality, and Cosplay: a Case Study of Male-To-Female Crossplay

Gender, Sexuality, and Cosplay: A Case Study of Male-to-Female Crossplay The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation “Gender, Sexuality, and Cosplay: A Case Study of Male-to-Female Crossplay,” The Phoenix Papers: First Edition, (Apr 2013), 89-110. ISSN: 2325-2316. Published Version http://fansconf.a-kon.com/dRuZ33A/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/ Gender-Sexuality-and-Cosplay-by-Rachel-Leng1.pdf;http:// fansconf.a-kon.com/dRuZ33A/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Gender- Sexuality-and-Cosplay-by-Rachel-Leng1.pdf Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:13481274 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Gender, Sexuality, and Cosplay: A Case Study of Male-to-Female Crossplay Rachel Leng "Let's get one thing straight. I am not gay. I like girls a lot. That‟s why most of my favorite anime characters are girls. I like them so much that I sometimes dress up like them." Tenshi, Crossplay.net, quoted on “Why Crossplay?” forum,(May 2012). “Good crossplay reveals the pure love for an anime character […] that is at the heart of all cosplay, regardless of the gender of [the] cosplayer or the character being cosplayed. In my perspective, it takes a real man to dress like a 10-year-old girl.” Lyn, Cosplay.com, quoted on “Views on Crossplay” thread (Oct. -

Superheroes & Stereotypes: a Critical Analysis of Race, Gender, And

SUPERHEROES & STEREOTYPES: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF RACE, GENDER, AND SOCIAL ISSUES WITHIN COMIC BOOK MATERIAL Gabriel Arnoldo Cruz A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2018 Committee: Alberto González, Advisor Eric Worch Graduate Faculty Representative Joshua Atkinson Frederick Busselle Christina Knopf © 2018 Gabriel Arnoldo Cruz All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Alberto González, Advisor The popularity of modern comic books has fluctuated since their creation and mass production in the early 20th century, experiencing periods of growth as well as decline. While commercial success is not always consistent from one decade to the next it is clear that the medium has been and will continue to be a cultural staple in the society of the United States. I have selected this type of popular culture for analysis precisely because of the longevity of the medium and the recent commercial success of film and television adaptations of comic book material. In this project I apply a Critical lens to selected comic book materials and apply Critical theories related to race, class, and gender in order to understand how the materials function as vehicles for ideological messages. For the project I selected five Marvel comic book characters and examined materials featuring those characters in the form of comic books, film, and television adaptations. The selected characters are Steve Rogers/Captain America, Luke Cage, Miles Morales/Spider-Man, Jean Grey, and Raven Darkholme/Mystique. Methodologically I interrogated the selected texts through the application of visual and narrative rhetorical criticism. -

Abstract the Gendered Superhero

i ABSTRACT THE GENDERED SUPERHERO: AN EXAMINATION OF MASCULINITIES AND FEMININITIES IN MODERN AGE DC AND MARVEL COMIC BOOKS Jennifer Volintine, M.A. Department of Anthropology Northern Illinois University, 2016 Kendall M. Thu, Director This thesis examines American gender concepts of masculinity and femininity depicted in six Modern Age superhero comic books. Specifically, it examines how the American gender concepts of hegemonic masculinity, hypersexualized masculinity, emphasized femininity, and hypersexualized femininity are depicted in three Marvel and three DC comic books. This examination found that despite gender differences defined by biological essentialism that legitimates gender inequality, female and male superheroes are much more alike than different through what I term ―visionary gender.‖ Also, it examines indicators of gender not previously examined in American superhero comic books. In particular, it examines the text of superhero comic books to demonstrate that language use in comic books is gendered and that female superheroes use interruption as a way to control and dominate male superheroes in conversation. In addition, two viewpoints within the comic book subculture are examined: the comic book readers and the comic book artists. It addresses the readers‘ interpretation of gender depicted in a selection of images illustrating superhero characters‘ bodies and it observes the artists‘ intention in illustrating superhero characters with respect to gender. i NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DE KALB, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 THE GENDERED SUPERHERO: AN EXAMINATION OF MASCULINITIES AND FEMININITIES IN MODERN AGE DC AND MARVEL COMIC BOOKS BY JENNIFER VOLINTINE ©2016 Jennifer Volintine A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY Thesis Director: Kendall M. -

Histories of Gender & Sexual Diversity in Games

Memory Insufficient the games history e-zine Queering Histories of history in NES ROMs gender & sexual PLUS diversity Gender villainy, Queer genealogies, in games and four histories Issue three of character creation June 2013 Cover image from Helly Kitty World, courtesy of Party Time Hexcellent This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution - Non-commercial - NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. See more information. Memory Insufficient the games history e-zine About the Editor: Zoya Street is a freelance video game historian, journalist and writer, working in the worlds of design criticism and digi- tal content business strategy. zoyastreet.com | @rupazero Memory Insufficient is a celebration of history. First and foremost, it is an attempt to promote and encourage historical writing about games; social histories, biographies, historically situated criticism of games and anything else. It is also a place to turn personal memories of games past into eye-opening written accounts. It is a place to honour the work of game developers who have influenced the path of history. It is a place to learn what games are - not as a formal discipline, but as lived realities. Like all historical study, Memory Insufficient is fundamentally about citizenship. It’s not enough to just remember and admire the games of the past. History is about understanding our place in the world; as developers, as critics and as players. The power of history is to reveal where the agents of change reside, and empower us to be the change we want to see. Memory Insufficient is a celebration of history, not just as fact but as action. -

Cosplaying with Gender: Freedoms and Limitations to Gender Exploration at Canadian Anime Conventions

COSPLAYING WITH GENDER: FREEDOMS AND LIMITATIONS TO GENDER EXPLORATION AT CANADIAN ANIME CONVENTIONS by Victoria E. Lemmons A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Women’s and Gender Studies Pauline Jewett Institute of Women’s and Gender Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2019 Victoria E. Lemmons Abstract This thesis investigates the gendered dimensions of cosplay and cross-play at Canadian anime conventions. How do cosplayers use cross-play to explore gender identities at anime conventions? What limitations hinder cosplayers from feeling free to explore their identities at these events? Why do cis women and non-binary people assigned female at birth (AFAB) participate in cross-play? I use in-depth interviews with cosplayers, autoethnography, and textual analyses of convention anti-harassment policies to explore these questions. Cross-play at Canadian anime conventions is beneficial to queer, trans, and non-binary attendees as they are able to explore their gender presentations in unique ways. Yet, there are limitations to this freedom, particularly for cis women and non-binary AFAB cosplayers who experience negativity surrounding femininity and heightened sexual harassment. These findings broaden understandings of gender and anime fan practices and encourage convention organizers to update policies on harassment. ii Acknowledgements I am indebted to the cosplay community in so many ways. It is thanks to my participants that I was able to produce this thesis. Convention organizers and volunteers made it possible for me to first encounter the world of cosplay. I’ve enjoyed attending different anime conventions across Canada, and I hope they continue to flourish as the years progress. -

The Marginalization of Female Creators and Consumers in Comics

INKING OVER THE GLASS CEILING: THE MARGINALIZATION OF FEMALE CREATORS AND CONSUMERS IN COMICS A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University School of Art in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. by Maria Campbell August, 2015 Thesis written by Maria Campbell B.F.A, Lesley University, 2011 M.F.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by Diane Scillia, Ph.D., Advisor Christine Havice, Ph.D., Director, School of Art John R. Crawford, Ed.D., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………….v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………viii AUTHOR’S NOTE……………………………………………………………….ix INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER ONE THE ORIGINS OF COMICS AND THE GOLDEN AGE……………………….6 The Early History of Comic Strips…………………………………………...6 World War II and the Golden Age……………………………………….......9 Wonder Woman and Her Creators………………………………………….11 The Seduction of the Innocent………………………………………….......13 Jackie Ormes………………………………………………………………..17 The Silver (1956-1970) and Bronze Ages (1970-1985) of Comics Sales…..19 CHAPTER TWO UNDERGROUND COMICS TO MODERN DAY..……………………………23 Pop Art and Comix………………………………………………………....23 Feminist Anthologies……………………………………………………….26 Alternative Comics and Graphic Novels……………………………………27 Women in Refrigerators…………………………………………………….31 “No Girls Allowed” in Comic Books……………………………………….34 Feminist Writers and Heroines…………………………………………......37 Bitch Planet…………………………………………………………………42 CHAPTER THREE MANGA IN AMERICA AND WEBCOMICS….................................................45 -

Pretty T Girls June 2013 the Magazine for the Most Beautiful Girls in the World

1 Pretty T Girls June 2013 The Magazine for the most beautiful girls in the world A publication of Pretty T Girls Yahoo group 2 Pretty T Girls The Magazine for the most beautiful girls in the world A publication of Pretty T Girls Yahoo group 3 In This Issue Page Editorial By: Barbara Jean 4 Lip Color: Gloss, Stain, Lipstick, Balm & More 5 How to Apply Eye Makeup Based On Your Eye Shape 8 Makeup Trends That Still Haven’t Died 10 Rhonda’s Ramblings 11 Transgendered In Romania Part 2 12 The Exploits of Barbara Marie 14 Tasi’s Musings 16 Scientist Discover Transsexual Gene 21 Humor 23 Angels in the Centerfold 24 TG Tips by Mellissa 25 My Anime-Zing Adventure by: Mellissa Lynn 30 The Adventures of Judy Sometimes 34 The Ramblings of a Married T-Girl 35 Tasi’s Fashion News 38 Do High Heels Put 100 Times More Stress On Your Feet 41 You Can Judge 90% of People by Their Shoes 43 Banning Boob Sweat 45 What to Wear for Any Occasion 47 Lucille Sorella 53 The Gossip Fence 54 Shop Till You Drop 67 Calendar 74 4 GLB T An Editorial by: Barbara Jean On one of my board there was a question about a rumor of the T separating from the GLB. Well this rumor has been actually going on for many years. For years it been felt that the gay/ lesbian community was saying “let us get our rights and then we will come back for yours.” There have been many hard feeling of the gay/lesbian community by the transgender community especially after the debacle by HRC where Joe Solomonese at the Southern Conference had said that HRC would not support any ENDA that did not include gender, but then right after saying that Rep. -

Liberez Le Batman En Vous » Le Cosplay Et La Consommation De Genre

14èmes Journées Normandes de Recherches sur la Consommation : Société et Consommation 26-27 Novembre 2015, Angers « LIBEREZ LE BATMAN EN VOUS » LE COSPLAY ET LA CONSOMMATION DE GENRE Alexandre TIERCELIN Marion GARNIER Maitre de Conférences Professeur Associé Laboratoire REGARDS LSMRC – M.E.R.C.U.R. IUT de Troyes, Université de Reims SKEMA Business School – Université de Champagne Ardennes Lille [email protected] [email protected] « LIBEREZ LE BATMAN EN VOUS » LE COSPLAY ET LA CONSOMMATION DE GENRE RESUME : Au début des années 2000, Butler remet en question la notion de genre au travers de la transexualité. Face à l’actualité de la soi-disante Gender Theory en France, cette recherche questionne les travaux académiques sur le genre, au travers du cas du cosplay. La collecte de données par le biais d’une netnographie sur la principale communauté de cosplayers français et d’une ethnographie dans les conventions met en évidence les motivations et les pratiques, notamment DIY, attachées à ce loisir. Elle permet de discuter ensuite de l’opportunité de consommation de genre qui peut se manifester dans le cas spécifique du crossplay. MOTS-CLÉS: gender studies, cosplay, crossplay, sous-culture geek “UNLEASH YOU INNER BATMAN” COSPLAY AND GENDER CONSUMPTION ABSTRACT: In the early 2000’s, Butler challenged the notion of gender through transsexualism. As the so-called “Gender Theory” echoes in France, this research questions academic works on gender, through the case of cosplay. The data collection through a netnography on the main French cosplayers community and an ethnography in conventions highlights motivations and practices, notably DIY, linked to this leisure. -

An Exploration of Women in Gender-Bending Cosplay

Costuming as Inquiry: An Exploration of Women in Gender-Bending Cosplay Through Practice & Material Culture Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rebecca Baygents Turk, M.A. Graduate Program in Arts Administration, Education and Policy The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Dr. Shari L. Savage, Advisor Dr. Christine Ballengee Morris Dr. Jennifer Schlueter 1 Copyrighted by Rebecca Baygents Turk 2019 2 Abstract This study explores the phenomenon of gender-bending cosplay (GBC) through its material culture using costuming (the acts of making and wearing artifacts and the artifacts themselves) to examine the motivations/interests/expectations of women who participate. GBC embraces the shifting, or bending, of the identified gender and/or biological sex of a fictional character to match the gender identity and/or biological sex of the player. This study concentrates on self-identified women adapting male characters to female versions of the same characters. The principal approach of the research design is Practice as Research (PaR) from an Art-Based Research (ABR) paradigm. Research methods include costuming, performance, ethnography, narrative inquiry, interviewing, participant observation, and discourse analysis. The worlds of text and image are melded in the amphibious, mixed-methods design and presentations of this study. GBC involves creating and using material culture, the artifacts of a culture/community. It becomes a creative outlet for many who may not otherwise be making art. When material culture can be worn, an interactive embodied performance can be experienced between the maker and the player, the player and the artifacts, the player and the audience, the player and fellow players, the player and cultural texts.