Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern Shale Gas Development in the United States: a Primer

U.S. Department of Energy • Office of Fossil Energy National Energy Technology Laboratory April 2009 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe upon privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. Modern Shale Gas Development in the United States: A Primer Work Performed Under DE-FG26-04NT15455 Prepared for U.S. Department of Energy Office of Fossil Energy and National Energy Technology Laboratory Prepared by Ground Water Protection Council Oklahoma City, OK 73142 405-516-4972 www.gwpc.org and ALL Consulting Tulsa, OK 74119 918-382-7581 www.all-llc.com April 2009 MODERN SHALE GAS DEVELOPMENT IN THE UNITED STATES: A PRIMER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Fossil Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) under Award Number DE‐FG26‐ 04NT15455. Mr. Robert Vagnetti and Ms. Sandra McSurdy, NETL Project Managers, provided oversight and technical guidance. -

CONODONT BIOSTRATIGRAPHY and ... -.: Palaeontologia Polonica

CONODONT BIOSTRATIGRAPHY AND PALEOECOLOGY OF THE PERTH LIMESTONE MEMBER, STAUNTON FORMATION (PENNSYLVANIAN) OF THE ILLINOIS BASIN, U.S.A. CARl B. REXROAD. lEWIS M. BROWN. JOE DEVERA. and REBECCA J. SUMAN Rexroad , c.. Brown . L.. Devera, 1.. and Suman, R. 1998. Conodont biostrati graph y and paleoec ology of the Perth Limestone Member. Staunt on Form ation (Pennsy lvanian) of the Illinois Basin. U.S.A. Ill: H. Szaniawski (ed .), Proceedings of the Sixth European Conodont Symposium (ECOS VI). - Palaeont ologia Polonica, 58 . 247-259. Th e Perth Limestone Member of the Staunton Formation in the southeastern part of the Illinois Basin co nsists ofargill aceous limestone s that are in a facies relati on ship with shales and sandstones that commonly are ca lcareous and fossiliferous. Th e Perth conodo nts are do minated by Idiognathodus incurvus. Hindeodus minutus and Neognathodu s bothrops eac h comprises slightly less than 10% of the fauna. Th e other spec ies are minor consti tuents. The Perth is ass igned to the Neog nathodus bothrops- N. bassleri Sub zon e of the N. bothrops Zo ne. but we were unable to co nfirm its assignment to earliest Desmoin esian as oppose d to latest Atokan. Co nodo nt biofacies associations of the Perth refle ct a shallow near- shore marine environment of generally low to moderate energy. but locali zed areas are more variable. particul ar ly in regard to salinity. K e y w o r d s : Co nodo nta. biozonation. paleoecology. Desmoinesian , Penn sylvanian. Illinois Basin. U.S.A. -

Harrodsburg Limestone in Kentucky

Harrodsburg Limestone In Kentucky By E. G. SABLE, R. C. KEPFERLE, and W. L. PETERSON CONTRIBUTIONS TO STRATIGRAPHY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1224-1 Prepared in cooperation with the Com monwealth of Kentucky, University of Kentucky, Kentucky Geological Survey UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1966 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 10 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Fag* Abstract.________________________________________________________ II Introduction.____________________________-_--____--____-__--_-_--_ 1 History of nomenclature_________________ ______________________ 1 Harrodsburg Limestone redefined in Kentucky._______________________ 6 Round Hollow section__-__-___-_---____._-___-_----__-._.__--_.__ 7 Correlations._____________________________________________________ 11 References cited.................__________________________________ 11 ILLUSTRATIONS Pag» FIGURE 1. Stratigraphic nomenclature of selected Mississippian units in 12 northwest-central Kentucky __________________________ 2. Map of central Kentucky showing counties and topographic quadrangles referred to in this re port..____.___.._.__.__.__ 4 ill 799-251 66 CONTRIBUTIONS TO STRATIGRAPHY HARRODSBURG LIMESTONE IN KENTUCKY By E. G. SABLE, R. C. KEPFERLE, and W. L. PETERSON ABSTRACT The Harrodsburg Limestone (Mississippian) in northwest-central Kentucky consists of 20 to 50 feet of light-gray coarse-grained fossil-fragmental limestone and minor silty limestone. It underlies the Salem Limestone, overlies the Borden Formation, and includes the Leesville and Guthrie Creek Members, of the Lower Harrodsburg of P. B. Stockdale and the Harrodsburg (restricted) as used by him. INTRODUCTION The name Harrodsburg Limestone was given (Hopkins and Sieben- tlial, 1897) to a unit of predominantly carbonate rocks of Mississippian age in Indiana and was subsequently used in Kentucky. -

Subsurface Facies Analysis of the Devonian Berea Sandstone in Southeastern Ohio

SUBSURFACE FACIES ANALYSIS OF THE DEVONIAN BEREA SANDSTONE IN SOUTHEASTERN OHIO William T. Garnes A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2014 Committee: James Evans, Advisor Jeffrey Snyder Charles Onasch ii ABSTRACT James Evans, Advisor The Devonian Berea Sandstone is an internally complex, heterogeneous unit that appears prominently both in outcrop and subsurface in Ohio. While the unit is clearly deltaic in outcrops in northeastern Ohio, its depositional setting is more problematic in southeastern Ohio where it is only found in the subsurface. The goal of this project was to search for evidence of a barrier island/inlet channel depositional environment for the Berea Sandstone to assess whether the Berea Sandstone was deposited under conditions in southeastern Ohio unique from northeastern Ohio. This project involved looking at cores from 5 wells: 3426 (Athens Co.), 3425 (Meigs Co.), 3253 (Athens Co.), 3252 (Athens Co.), and 3251 (Athens Co.) In cores, the Berea Sandstone ranges from 2 to 10 m (8-32 ft) thick, with an average thickness of 6.3 m (20.7 ft). Core descriptions involved hand specimens, thin section descriptions, and core photography. In addition to these 5 wells, the gamma ray logs from 13 wells were used to interpret the architecture and lithologies of the Berea Sandstone in Athens Co. and Meigs Co. as well as surrounding Vinton, Washington, and Morgan counties. Analysis from this study shows evidence of deltaic lobe progradation, abandonment, and re-working. Evidence of interdistributary bays with shallow sub-tidal environments, as well as large sand bodies, is also present. -

From Forests to Farms and Towns: State Parks and Settlement of Indiana

From Forests to Farms and Towns: State Parks and Settlement of Indiana Key Objectives State Parks Featured This unit is designed to help students learn about the challenges ■ Turkey Run State Park (www.stateparks.IN.gov/2964.htm) that Indiana’s early settlers faced by looking at the lives of four ■ Spring Mill State Park (www.stateparks.IN.gov/2968.htm) families who settled on land that eventually became part of ■ Mounds State Park (www.stateparks.IN.gov/2977.htm) Indiana’s state parks system. ■ Lincoln State Park (www.stateparks.IN.gov/2979.htm) ■ Potato Creek State Park (www.stateparks.IN.gov/2972.htm) Activity: Standards: Benchmarks: Assessment Tasks: Key Concepts: Daily life in the first half of the 18th century Tools used by Be able to describe the challenges of daily early settlers Daily Life Explain how key individuals and events life as a settler of Indiana’s frontier during for Indiana SS.4.1.6 influenced the early growth and development the pioneer era. Students will research African-Americans Settlers of Indiana. source materials and write a skit about in Indiana daily life in early Indiana. What cemeteries tell us Trade and industry Be able to describe the challenges of daily Give examples of Indiana’s increasing agricul- life as a settler of Indiana’s frontier during tural, industrial, political and business develop- SS.4.1.9 the pioneer era. Students will research ment in the 19th century. source materials and write a skit about daily life in early Indiana. Be able to describe the challenges of daily life as a settler of Indiana’s frontier during the pioneer era. -

The Lower Carboniferous Area

THE GEOLOGY OF The Lower Carboniferous Area OF SOUTHERN INDIANA. BY GEORGE HALL ASHLEY, PH. D., Assisted by EDW ARD M. KINDLE, PH. D. -49- LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL . INDIANAPOLIS, IND., January 15, 1902. Hon. W. S. Blatchley, State Geologist of Indiana: Sir-I have the honor to hand you herewith my report on the ge ology of the area of the Lower Carboniferous rocks of Bouthern Indiana. This work was planned, in accordanc'e with your instruc tions, primarily as a continuation of the survey of the Bedford Oolitic Limestone made north of Orange County in 1896. Pursuant to your instructions, however, the other members of the Lower Carboniferous have been mapped, and examined, 'especially for any strata of economic value. The most valuable part ot the report is believed to be given on the accompanying maps, which attempt to show the distribution of the different formations with as much or greater accuracy than has hitherto been attempted in this State. They also show graphic'ally the character of the topography by pro files, and the structure of the strata as a whole. In addition a columnar section is added. In order to complete the work in the time allotted it wa.s necessary to omit much work that would have been necessary for the mapping of the quaternary and the forma tion herein called the "Ohio River Formation," believed to be of Tertia,ry age. The field work occupied the season of 190(). The writer was assisted by Dr. Edward M. Kindle. 'rhe writer is entirely responsible for the maps and reports of Washington and Harrison counties. -

What's New in State Parks and Reservoirs in 2014

Visit us online at www.stateparks.IN.gov What’s New in State Parks and Reservoirs in 2014 Enjoy this snapshot of some of the work we have done to prepare for your visits in 2014. Please know that there are hundreds of other projects and events not mentioned that are also designed to manage and interpret the facilities, natural and cultural resources, and history of Indiana’s state parks and reservoirs. Much of the work completed in 2014 did not involve new construction or major infrastructure overhauls. We have more than 2,000 buildings, 700 miles of trails, 631 hotel/lodge rooms, 75 marinas, 16 swimming pools, 15 beaches, almost 8,400 campsites, more than 200 shelters, 160 or so playgrounds and 149 cabins. That’s a lot of maintenance. In these tight fiscal conditions, most of our time and energy has been focused on basic facility care. We have wonderful partners and volunteers who help us accomplish a variety of projects. Our Friends groups contributed thousands of dollars and hours for projects and events. We have creative and dedicated staff who stretch the dollars that you pay when you enter the gate, rent a campsite, launch a boat or attend a special workshop or program. Our goal is to provide you with a great experience during every visit. Your Indiana state parks and reservoirs are a great value, both in cost and in serving as great places to get healthy, relax in the outdoors and create great stories and memories for the future. Get outside with your family and friends – you’ll be glad you did. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places _ j,, -,-4 Registration Form HISTORY This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties antf'djstricts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register BullefifneA). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Shakamak State Park Historic District other names/site number 2. Location street & number 6165 West State Rn?H 48 N/A D not for publication city or town .Tasonville___________ ———H vicinity State Indiana_______ COde TN county Clay code zip code 47418 3. State/Federal Agency Certification "I As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this H nomination G request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property K meets D does not meet the Natjonal Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally £3 statewide J^r loyally. -

LONG DISTANCE HIKING TRAILS Welcome to Indiana State Parks and Reservoirs

34 DNR 2007 Special Events Programs are open to the public, suitable for all ages and with some exceptions, free with admission to the property. Welcome to Indiana State Parks and Reservoirs’ Walk, hike, swim, ride and relax your way to better health at your favorite state park or reservoir. As you spend time outdoors, you’ll see that our Hoosier state properties feature great natural resources, ranging from giant sand dunes to deep rocky canyons. They are priceless gems and it takes staff, expertise and funding to manage and protect them. Visit www.dnr.IN.gov/healthy on the web for more information. Ten Simple Ways.... ....you can improve your health at a state park or reservoir. • Walk a trail. • Rent a canoe or boat and go for a paddle. • Take a swim at a pool or beach. • Have a picnic and visit the playground. • Join our staff for a guided nature hike. • Ride a bike on one of our paved trails or our mountain bike trails. • Turn off your cell phone and computer Make a date to get INShape at state parks and and relax in a lawn chair at a picnic area. reservoirs on Saturday, May 5 and Saturday, • Waterski on one of our nine reservoirs. September 8. Admission to your favorite • Buy a GPS unit and learn to geocache. property is free with an INShape coupon • Take a child fishing. downloaded from www.INShape.IN.gov, and features staff-led exercise walks at most properties. Coupons will be available two weeks before each INShape DNR Day. -

Environmental Education Resource Directory

EE Resource Directory Introduction The Environmental Education Association of Indiana has compiled this directory to assist educators in selecting and accessing resources for environmental education in the classroom. Those who work with adults and non-formal youth groups, such as scouts and 4-H, may also find these resources useful in planning activities for meetings, workshops, camp, and other occasions. The directory is organized into two main sections, those organizations that serve the entire state and those that serve a limited area, such as a county or region. Within the two main sections, you will find public agencies, including federal, state, county, and city departments, and private organizations, such as soil and water conservation districts, conservation organizations, and individuals who are available to share music, stories, or songs. If you have corrections or additions to this list, please contact Cathy Meyer at Monroe County Parks and Recreation, 119 West Seventh Street, Bloomington, IN 47404, 812- 349-2805, How to Get the Most From These Resources The organizations and people listed here are experts who are willing to share a vast array of knowledge and materials with you. There are a few ways to make the most of your contacts with them. These contacts are intended primarily for use by adults, not for student research projects. Before contacting anyone, be clear about your educational objectives. Many of the programs are based on state science standards to help you in meeting educational requirements. Will your objectives best be met with classroom activities, activities using the school grounds, or visits to special sites away from school? Do you need activity ideas, supplementary videos, material or equipment to borrow, or a speaker? What level of understanding should students have after the program? What will they know beforehand and what will you do to follow-up? Many agencies offer preliminary training for teachers using their programs or they may have pre-visit or follow-up activities for you to use. -

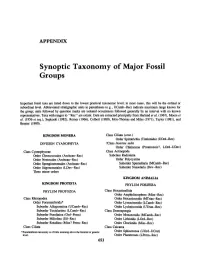

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

![Italic Page Numbers Indicate Major References]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6112/italic-page-numbers-indicate-major-references-2466112.webp)

Italic Page Numbers Indicate Major References]

Index [Italic page numbers indicate major references] Abbott Formation, 411 379 Bear River Formation, 163 Abo Formation, 281, 282, 286, 302 seismicity, 22 Bear Springs Formation, 315 Absaroka Mountains, 111 Appalachian Orogen, 5, 9, 13, 28 Bearpaw cyclothem, 80 Absaroka sequence, 37, 44, 50, 186, Appalachian Plateau, 9, 427 Bearpaw Mountains, 111 191,233,251, 275, 377, 378, Appalachian Province, 28 Beartooth Mountains, 201, 203 383, 409 Appalachian Ridge, 427 Beartooth shelf, 92, 94 Absaroka thrust fault, 158, 159 Appalachian Shelf, 32 Beartooth uplift, 92, 110, 114 Acadian orogen, 403, 452 Appalachian Trough, 460 Beaver Creek thrust fault, 157 Adaville Formation, 164 Appalachian Valley, 427 Beaver Island, 366 Adirondack Mountains, 6, 433 Araby Formation, 435 Beaverhead Group, 101, 104 Admire Group, 325 Arapahoe Formation, 189 Bedford Shale, 376 Agate Creek fault, 123, 182 Arapien Shale, 71, 73, 74 Beekmantown Group, 440, 445 Alabama, 36, 427,471 Arbuckle anticline, 327, 329, 331 Belden Shale, 57, 123, 127 Alacran Mountain Formation, 283 Arbuckle Group, 186, 269 Bell Canyon Formation, 287 Alamosa Formation, 169, 170 Arbuckle Mountains, 309, 310, 312, Bell Creek oil field, Montana, 81 Alaska Bench Limestone, 93 328 Bell Ranch Formation, 72, 73 Alberta shelf, 92, 94 Arbuckle Uplift, 11, 37, 318, 324 Bell Shale, 375 Albion-Scioio oil field, Michigan, Archean rocks, 5, 49, 225 Belle Fourche River, 207 373 Archeolithoporella, 283 Belt Island complex, 97, 98 Albuquerque Basin, 111, 165, 167, Ardmore Basin, 11, 37, 307, 308, Belt Supergroup, 28, 53 168, 169 309, 317, 318, 326, 347 Bend Arch, 262, 275, 277, 290, 346, Algonquin Arch, 361 Arikaree Formation, 165, 190 347 Alibates Bed, 326 Arizona, 19, 43, 44, S3, 67.