492191 Vol1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trent 91; First Steps Towards a Stylistic Classification (Revised 2019 Version of My 2003 Paper, Originally Circulated to Just a Dozen Specialists)

Trent 91; first steps towards a stylistic classification (revised 2019 version of my 2003 paper, originally circulated to just a dozen specialists). Probably unreadable in a single sitting but useful as a reference guide, the original has been modified in some wording, by mention of three new-ish concordances and by correction of quite a few errors. There is also now a Trent 91 edition index on pp. 69-72. [Type the company name] Musical examples have been imported from the older version. These have been left as they are apart from the Appendix I and II examples, which have been corrected. [Type the document Additional information (and also errata) found since publication date: 1. The Pange lingua setting no. 1330 (cited on p. 29) has a concordance in Wr2016 f. 108r, whereti it is tle]textless. (This manuscript is sometimes referred to by its new shelf number Warsaw 5892). The concordance - I believe – was first noted by Tom Ward (see The Polyphonic Office Hymn[T 1y4p0e0 t-h15e2 d0o, cpu. m21e6n,t se suttbtinigt lneo] . 466). 2. Page 43 footnote 77: the fragmentary concordance for the Urbs beata setting no. 1343 in the Weitra fragment has now been described and illustrated fully in Zapke, S. & Wright, P. ‘The Weitra Fragment: A Central Source of Late Medieval Polyphony’ in Music & Letters 96 no. 3 (2015), pp. 232-343. 3. The Introit group subgroup ‘I’ discussed on p. 34 and the Sequences discussed on pp. 7-12 were originally published in the Ex Codicis pilot booklet of 2003, and this has now been replaced with nos 148-159 of the Trent 91 edition. -

Voir Les Saints Du Mois De Septembre

1er septembre 1. Commémoraison de saint Josué, fils de Nun, serviteur du Seigneur, vers 1220. Quand Moïse lui eut imposé les mains, il fut rempli de l’esprit de sagesse et, après la mort de Moïse, fit passer le peuple d’Israël à travers le lit du Jourdain et l’introduisit dans la terre promise d’une manière merveilleuse. 2. À Reims, en Gaule Belgique au IIème siècle, saint Sixte, reconnu comme premier évêque de la cité. 3. À Capoue en Campanie, sur la voie Aquaria, vers le IVème siècle, saint Prisque, martyr. 4. À Todi en Ombrie, vers le IVème siècle, saint Térentien, évêque. 5. À Dax en Aquitaine, vers le IVème siècle, saint Vincent, vénéré comme évêque et martyr. 6. À Zurzach sur le Rhin, dans le canton d’Argovie en Suisse, au IVème siècle, sainte Vérène, vierge. 7. Au Mans en Gaule Lyonnaise, vers 490, saint Victeur, évêque, dont saint Grégoire de Tours fait mention. 8. Près d’Aquin dans le Latium, vers 570, saint Constance, évêque. Le pape saint Grégoire le Grand fit l'éloge de son don de prophétie. 9. Dans la région de Nîmes en Gaule Narbonnaise, au VIème ou VIIème siècle, saint Gilles, dont le nom a été donné à la ville qui s’est établie ensuite dans la vallée Flavienne, où lui-même aurait érigé un monastère et terminé sa vie mortelle. 10. À Sens, en Neustrie vers 623, saint Loup, évêque. Il subit l’exil pour avoir eu l’audace de déclarer, devant un important personnage du lieu, que le devoir de l’évêque est de diriger le peuple et qu’il faut obéir à Dieu plutôt qu’aux princes. -

How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed. Julie Ellen Kane Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1999 How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed. Julie Ellen Kane Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Kane, Julie Ellen, "How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed." (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6892. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6892 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been rqxroduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directfy firom the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fiice, vdiile others may be from any typ e o f com pater printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^innm g at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

PMMS L'homme Arme' Masses Discography

Missa L’homme armé Discography Compiled by Jerome F. Weber This discography of almost forty Masses composed on the cantus firmus of L’homme armé (twenty- eight of them currently represented) makes accessible a list of this group of recordings not easily found in one place. A preliminary list was published in Fanfare 26:4 (March/April 2003) in conjunction with a recording of Busnoys’s Mass. The composers are listed in the order found in Craig Wright, The Maze and the Warrior (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2001), p. 288; the list is alphabetical within broad eras. In particular, he discusses Du Fay (pp. 175ff.), Regis (pp. 178ff.), the Naples Masses (pp. 184ff.), and Josquin des Prez (pp. 188ff.). Richard Taruskin, “Antoine Busnoys and the L’Homme armé Tradition,” Journal of AMS, XXXIX:2 (Summer 1986), pp. 255-93, writes about Busnoys and the Naples Masses, suggesting (pp. 260ff.) that Busnoys’s Mass is the earliest of the group and that the Naples Masses are also by him. Fabrice Fitch, Johannes Ockeghem: Masses and Models (Paris, 1997, pp. 62ff.), suggests that Ockeghem’s setting is the earliest. Craig Wright, op. cit. (p. 175), calls Du Fay’s the first setting. Alejandro Planchart, Guillaume Du Fay (Cambridge, 2018, p. 594) firmly calls Du Fay and Ockeghem the composers of the first two Masses, jointly commissioned by Philip the Good in May 1461. For a discussion of Taruskin’s article, see Journal of AMS, XL:1 (Spring 1987), pp. 139-53 and XL:3 (Fall 1987), pp. 576-80. See also Leeman Perkins, “The L’Homme armé Masses of Busnoys and Okeghem: A Comparison,” Journal of Musicology, 3 (1984), pp. -

From Historical Concerts to Monumental Editions: the Early Music Revivals at the Viennese International Exhibition of Music and Theater (1892)

From Historical Concerts to Monumental Editions: The Early Music Revivals at the Viennese International Exhibition of Music and Theater (1892) María Cáceres-Piñuel All content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Received: 28/08/2019 Published: 03/04/2021 Last updated: 03/04/2021 How to cite: María Cáceres-Piñuel, “From Historical Concerts to Monumental Editions: The Early Music Revivals at the Viennese International Exhibition of Music and Theater (1892),” Musicologica Austriaca: Journal for Austrian Music Studies (April 03, 2021) Tags: 19th century; Adler, Guido; Böhm, Josef; Cecilian Movement; Denkmäler der Tonkunst in Österreich (DTÖ); Early music programming ; Hermann, Albert Ritter von; Historical concerts; International Exhibition of Music and Theater (Vienna 1892); Joachim, Amalie; National monumental editions This article is part of the special issue “Exploring Music Life in the Late Habsburg Monarchy and Successor States,” ed. Tatjana Marković and Fritz Trümpi (April 3, 2021). Most of the archival research needed to write this article was made possible thanks to a visiting fellowship in the framework of the Balzan Research Project: “Towards a Global History of Music,” led by Reinhard Strohm. I have written this article as part of my membership at the Swiss National Science Fund (SNSF) Interdisciplinary Project: “The Emergence of 20th Century ‘Musical Experience’: The International Music and Theatre Exhibition in Vienna 1892,” led by Cristina Urchueguía. I want to thank Alberto Napoli and Melanie Strumbl for reading the first draft of this text and for their useful suggestions. The cover image shows Ernst Klimt’s (1864–92) lithograph for the Viennese Exhibition of 1892 (by courtesy Albertinaof Sammlungen Online, Plakatsammlung, Sammlung Mascha). -

A Stylistic Analysis

THE POLYPHONIC INTROITS OF TRENTO, ARCHIMO CAPITOLARE, MS 93: A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS Briao Edward Powcr A tbesis submitted ia conformity witb the requirements for the degree of Doetor of Philosopby Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 8 Copyrigbt by Brian Edward Power 1999 National Library Bibliothéque nationale B+B of Canada du Canada Acqiiisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliogiaphiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Otîawa ON KiA ON4 Ortawa ON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive Licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfichelfilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT The Polyphonie latroits of Tnnto, Archivio Copiolure, M.93: A Stylistic Analysis Doctor of Philosophy, 1999 Brian Edward Power Graduate Department of Music, University of Toronto Trent 93, the most recently discovered of the Trent Codices (a large and well- preserved source of fifteenthcenhuy sacred polyphony) contains a lengthy grouping of polyphonic settings of introits, the first item in the Proper of the Mass. -

Notes on Heinrich Isaac's Virgo Prudentissima Author(S): Alejandro Enrique Planchart Source: the Journal of Musicology, Vol

Notes on Heinrich Isaac's Virgo prudentissima Author(s): Alejandro Enrique Planchart Source: The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Winter 2011), pp. 81-117 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jm.2011.28.1.81 Accessed: 26-06-2017 18:47 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Musicology This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Mon, 26 Jun 2017 18:47:45 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Notes on Heinrich Isaac’s Virgo prudentissima ALEJandro ENRIQUE PLANCHART Thomas Binkley in memoriam In 1520 Sigmund Grimm and Marx Wirsung published their Liber selectarum cantionum quas vulgo mutetas appellant, a choirbook that combined double impression printing in the manner of Petrucci with decorative woodcuts. As noted in the dedicatory letter by the printers and the epilogue by the humanist Conrad Peutinger, the music was selected and edited by Ludwig Senfl, who had succeeded his teacher, Heinrich Isaac, as head of Emperor Maximilian’s chapel 81 until the emperor’s death in 1519. -

Reception of Josquin's Missa Pange

THE BODY OF CHRIST DIVIDED: RECEPTION OF JOSQUIN’S MISSA PANGE LINGUA IN REFORMATION GERMANY by ALANNA VICTORIA ROPCHOCK Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. David J. Rothenberg Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2015 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Alanna Ropchock candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree*. Committee Chair: Dr. David J. Rothenberg Committee Member: Dr. L. Peter Bennett Committee Member: Dr. Susan McClary Committee Member: Dr. Catherine Scallen Date of Defense: March 6, 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ........................................................................................................... i List of Figures .......................................................................................................... ii Primary Sources and Library Sigla ........................................................................... iii Other Abbreviations .................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... v Abstract ..................................................................................................................... vii Introduction: A Catholic -

Je Suis Ici À Viuz, Qui Est La Terre De Mon Évêché. François, Evêque De Genève, Lettre Du 20 Juillet 1607

SOMMAIRE - n° 3 - Editorial ......................... ...................... p. 2 St François, l’homme........................... p. 3 Statue à St François ............................ p .6 Retable ................................................. p. 9 Que de François ................................. p. 11 Lettre de St François ......................... p. 12 Translation des Reliques ................... p. 13 Religieux et St François .................... p. 14 Missions en Inde ................................ p. 15 St François à St Jean de Tholome .... p. 18 Falcinacus à F. .................................... p. 19 Miracles ................................................ p. 21 St François à Contamine .................... p. 22 Visite pastorale à Marcellaz ............... p. 24 Pensée de St François......................... p. 24 Transaction avec St François............. p. 25 St François à Peillonnex .................... p. 26 Viuz, visite pastorale .......................... p. 27 St François à Viuz, mandements ....... p. 28 Protestants, Catholiques .................... p. 29 Chapelle de Prévières.......................... p. 30 Chemin avec St François ................... p. 30 Un peu de tourisme ............................ p. 31 Cantique des Souvenirs .................... p. 32 Chant, Cantique .................................. p. 33 Vitraux de Fillinges ............................. p. 34 Je suis ici à Viuz, qui est la terre de mon évêché. François, Evêque de Genève, lettre du 20 juillet 1607 Numéro 3 - page 1 - Editorial Juste -

Volume 34 (2017)

BULLETIN OF MEDIEVAL CANON LAW NEW SERIES 2017 VOLUME 34 AN ANNUAL REVIEW PUBLISHED BY THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA PRESS BULLETIN OF MEDIEVAL CANON LAW BULLETIN OF MEDIEVAL CANON LAW NEW SERIES 2017 VOLUME 34 AN ANNUAL REVIEW PUBLISHED BY THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA PRESS Founded by Stephan G. Kuttner and Published Annually Editorial correspondence and manuscripts in electronic format should be sent to: PETER LANDAU AND KENNETH PENNINGTON, Editors The School of Canon Law The Catholic University of America Washington, D.C. 20064 [email protected] MELODIE H. EICHBAUER, Reviews and Bibliography Editor Florida Gulf Coast University Department of Social Sciences 10501 FGCU Blvd, South Fort Myers, Florida 33965 [email protected] Advisory Board PÉTER CARDINAL ERDŐ CHRISTOF ROLKER Archbishop of Esztergom Universität Bamberg Budapest FRANCK ROUMY ORAZIO CONDORELLI Université Panthéon-Assas Università degli Studi Paris II di Catania DANICA SUMMERLIN ANTONIA FIORI University of Sheffield La Sapienza, Rome JOSÉ MIGUEL VIÉJO-XIMÉNEZ PETER LINEHAN Universidad de Las Palmas de St. John’s College Gran Canaria Cambridge University Inquiries concerning subscriptions or notifications of change of address should be sent to the Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law Subscriptions, PO Box 19966, Baltimore, MD 21211-0966. Notifications can also be sent by email to [email protected] telephone 410-516-6987 or 1-800-548-1784 or fax 410-516-3866. Subscription prices: United States $75 institutions; $35 individuals. Single copies $80 institutions, $40 individuals. The articles in the Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law are abstracted in Canon Law Abstracts, Catholic Periodical and Literature Index and is indexed and abstracted in the Emerging Sources Citation Index ISSN: 0146-2989 Typeset annually and printed at 450 Fame Avenue, Hanover, PA 17331 by The Catholic University of America Press, Washington D.C. -

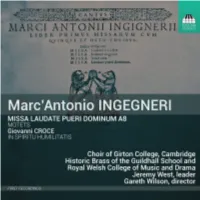

TOCC0556DIGIBKLT.Pdf

THE COUNCIL OF TRENT AND THE MUSIC OF MARC’ANTONIO INGEGNERI by Giampiero Innocente The Protestant Reformation was a storm which shook the Catholic church in every way: its dogmas, its hierarchies and the certainties of faith on which it had been based for 1,500 years were undermined at their very foundations. Luther and the reformers had called into question not only its theology and how it was articulated but also the nature of its community, its liturgy, its rituals and the music associated with them. A direct precursor of those musical changes was Luther’s translation of the Bible from Latin to German, completed in 1534, a work that became a true monument of the German language and a document that helped establish a ‘national’ identity. Although Luther had not totally rejected every musical form of the Catholic tradition – he preserved Latin hymns, for example – the new style of liturgical music he promoted was designed for a congregation that was no longer Catholic: the predominance of the Word of God, the abandonment of faith in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, and communion understood as being taken only ‘in memory’ of Christ’s Last Supper were fundamental elements that emboldened the newly reformed Protestant worship and generated new musical forms which were peculiar, and central, to it. Faced with this turn of events, the Catholic church gathered itself in order to launch a powerful ‘counter-reformation’ of its own, and between 1545 and 1563 its senior cardinals and clergy were convened to meet over a series of 25 sessions, now known as the Council of Trent, in order to respond to the attacks of the Protestant world that were spreading rapidly in northern Europe. -

Conseil Municipal Procès-Verbal Séance Du 7 Mars 2018 L'an DEUX MILLE DIX HUIT, LE SEPT MARS, À VINGT HEURES TRENTE, Le

Conseil municipal Procès-verbal Séance du 7 mars 2018 L’AN DEUX MILLE DIX HUIT, LE SEPT MARS, à VINGT HEURES TRENTE, le Conseil Municipal légalement convoqué, s’est réuni dans la Mairie en séance publique sous la présidence de Monsieur Marc PECHOUX, Maire PRESENTS : M. PECHOUX, C.TRASSARD, B.GUERIN, , A. IACOVELLI, JP.SAINT-CYR, G.LICHTLE, L.BORDELIER, , D.DESFORGES, S.PERNET, Y.GALLAY, G.GAGNE, P.BERTHAUD, A.TESSIAUT , A.SEMMADI, S.VERPAULT, D.BIDAULT, A.GENIN, M.RAYMOND, C.MONTESSUIT, P.CHARRONDIERE, G.BRULLAND EXCUSES AYANT DONNE POUVOIR : H.BONNET à G.LICHTLE, J.CORMORECHE à C.TRASSARD, M. CROUZAT à A.TESSIAUT, I.DE CARVALHO à P.BERTHAUD, I.VERRAT COTTE à L.BORDELIER, M.CACHAT à P.CHARRONDIERE, A.GOMES à M.RAYMOND ABSENTS : J. PARDON Lesquels forment la majorité des membres en exercice. Il a été, conformément aux dispositions de l’article L 2121 -15 du Code Général des Collectivités Locales procédé à la nomination d’un secrétaire de séance, C.TRASSARD ayant obtenu la majorité des suffrages, a été désigné pour remplir ces fonctions qu’il a acceptées. Informations préalables Le maire informe que la modification de règlement intérieur du conseil municipal sera à l’ordre du jour de prochain conseil municipal du 26 avril 2018. M. Raymond espère que ce ne sera pas pour diminuer les droits de la minorité. Prolongation de portage d’un bien r oute de Reyrieux (maison Guerre) : Le maire apporte une réponse à G.Brulland consernant les réserves foncières relatives à la maison Guerre (point 7 de la séance du 30 janvier 2018) : la délibération du 14/11/2013 portant convention de portage par l’EPF de l’Ain de la maison Guerre, route de Reyrieux, a été approuvée à l’unanimité des membr es.