Chinese Entanglements with Lower Franconian Business

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entlang Der Mainschleife

Entlang der Mainschleife Entfernung: ca. 12 km, Dauer: ca. 3,5 Std. Höhenprofil Die Mainschleife (03.09.2016, VGN © VGN GmbH) Vorwort Karte Vom Bahn hofsvorplatz in Kitzingen R1 aus starten wir unseren Karte am Ende des Dokuments in höherer Ausflug in Rich tung Mainschleife. Immer mal wieder am Main ent lang, Auflösung. geht es mit dem Mainschleifen-Express 107 dann durch die unterfrän kischen Weinorte Dettelbach, Sommerach, Nordheim und auch vorbei an der Abtei Münsterschwarzach. In allen Orten kann man sowohl bei der ersten Hin- als auch bei der Rück fahrt die Fahrt un ter- bre chen. Von Volkach aus umrunden wir auf unserer Tour fast die ge- Weg be schrei bung samte Volkacher Mainschleife: quer durch die Weinberge, zwei Überfahrten über den Main. Von der Bus hal te stel le am alten Bahn hof geht es am Brothaus Kohler vorbei aufwärts (Kühgasse). Oben dann links und durch das Jede Menge Aussichtspunkte und Ein kehr mög lich keiten lassen keine Obere Tor nach der St.-Bartholomäus-Kirche bis zum Markt platz. Langeweile aufkommen! Zusammen mit dem Marktbrunnen – 1480 erbaut und 1720 erneuert – und dem im Jahr 1544 fertiggestellten Rathaus sowie den alten Bürgerhäusern ein herrliches Fotomotiv. Stand: 8.7.2020 Seite 2 von 11 Seite 3 von 11 Tourist-In for ma ti on Volkacher Mainschleife Rathaus (EG) 97332 Volkach Tel: 09381 401-12 Fax: 09381 401-16 E-Mail: [email protected] Zwischen den Weinlagen (03.09.2016, VGN © VGN GmbH) www.volkach.de Jetzt weiter auf dem Panoramaweg, fädeln wir nach einem Öffn ungs zeiten: April bis Ok to ber: Mo-Mi von 8-12:30 Uhr und Rechtsbogen rechts aufwärts in einen geteerten Querweg ein. -

Fränkisches Weinland

Freizeitlinien 107, 108, 109 - Karte am Ende des Dokuments in höherer Auflösung. Fränkisches Weinland Flussauen-Erlebnis an der Volkacher Mainschliefe, Dorf-Romantik rund um die "Dorfschätze" und die frän kische Weinkultur des Karte am Ende des Dokuments in höherer Weinparadies Franken - die drei Weinregionen laden Sie ein zum Auflösung. Genießen und Entdecken der frän kischen Lebensart. Die Region rund um die Volkacher Mainschleife sowie rund um die „Dorfschätze“ im nördlichen Land kreis Kitzingen ist ein Paradies für Weinliebhaber. Nicht nur die endlos wirkenden Weinhänge, die sich z. Karte am Ende des Dokuments in höherer B. um den Schwanberg schmiegen, sondern auch die Kultur, das ku li- Auflösung. na rische An ge bot und das Lebensgefühl in einer der wärmsten Regionen Deutschlands laden zu einem Ausflug ein. Ein schönes Ziel ist die bekannte Weinparadiesscheune – identitätsstiftender Ort und Zentrum für Be su cher und Bewohner des Weinparadies Franken. Hier lässt sich bei einem gepflegten Glas Wein der grandiose Blick Fehler in der Tourenbeschreibung? weit über das Frankenland genießen. Korrekturen können an frei [email protected] geschickt werden. Für jede Zu den Winzern und Weinfesten gelangen Sie an Sams tagen, Sonn- Mithilfe, unsere Tipps so aktuell wie möglich zu halten, besten Dank! und Fei er tagen vom 1. Mai bis 1. No vem ber mit den VGN-Frei zeit li ni- en. VGN-App Der Mainschleifen-Express 107 fährt von Kitzingen über VGN Fahrplan & Tickets für Android, iOS und Windows Phone - mit Dettelbach, Münsterschwarzach, Sommerach, Nordheim nach Fahr plan aus künften, Fußwegekarten und Preis- und Ta rif an ga ben für Volkach und zurück. -

1 GERMANY Schweinfurt Case Study Report – D9 Dr

GERMANY Schweinfurt Case Study Report – D9 Dr. Ilona Biendarra Table of contents 1. Abstract 2 2. Presentation of the town 2 2.1 Introduction 2 2.2 Presentation of the majority and the minority presence 3 2.3 Presentation of the local welfare system 6 3. Context and timeframe 10 4. Methods and sources 11 4.1 Research focus and questions 11 4.2 Methods and material 12 4.3 Research sample 13 4.4 Conversations and focus/in-depth interviews 14 5. Findings 16 5.1 Communication, mutual understanding and social cohesion 16 5.2 Different definitions of family and women’s roles 22 5.3 Education and language support, but for whom? 26 5.4 Individual and alternative health care 29 5.5 Employment as a basis for integration 32 5.6 The local situation is in flux: an ongoing integration process 34 6. Analysis: emergent values 35 6.1 Welfare areas and values 36 6.2 Classification of values 40 6.3 Analysis conclusions 43 7. References 46 1 1. Abstract The study of values in Europe, observable through the prism of welfare, consists of an examination of the values of various groups in the domain of welfare, e.g. in the expression and provision of ‘basic’ individual and group needs. The different values and practices of the majority and the minorities are a source of tension in the German society. German policy tries to direct the interaction between majority and minorities towards more cohesion and solidarity. At the same time it becomes more obvious that minority groups influence and challenge majority values. -

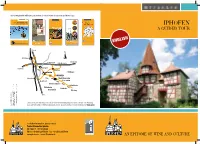

Iphofen a Guided Tour

The following leaflets will inform you on where to eat out, where to taste wine and where to go: GASTGEBERVERZEICHNIS ÜBERNACHTEN & EINKEHREN GASTGEBERVERZEICHNIS ÜBERNACHTEN & EINKEHREN IPHOFEN A GUIDED TOUR ENGLISH EINE WEINSTADT MIT KULTUR EINE WEINSTADT MIT KULTUR Kassel N Würzburg A7 Nürnberg Schwarzach Rüdenhausen A3 Frankfurt Kitzingen Rödelsee Mainbernheim Birklingen B8 IPHOFEN Ochsenfurt Markt Einersheim Marktbreit Possenheim Mönchsondheim Hellmitzheim Hüttenheim Dornheim Nenzenheim Nürnberg Ulm Stadt Iphofen, DLKM, Richard Schober, | schwarzach : DLKM Iphofen and its park+ride railway station are part of the Greater Nürnberg transport association (VGN). It offers 85 parking Layout: Picture credits Fränkisches Weinland, Knauf-Museum Translated by Erna Anderl-Fröhlich and Janet Baumann places and toilet facilities. A VGN ticket allows you to use 500 bus and rail services. For more information, visit www.vgn.de For further information, please contact Tourist Information Iphofen Kirchplatz 7 · 97346 Iphofen Phone +49 (0)9323/870306 · Fax +49 (0)9323/870308 www.iphofen.de · [email protected] AN EPITOME OF WINE AND CULTURE Welcome to Iphofen – welcome to past and present days The wine town of Iphofen stands out for its warm hospitality, excellent wine and culinary delights. Just like a precious painting, its meticulously restored ancient centre is framed by completely intact town walls. Its double town gates and towers bear witness of its strong fortifications, and a stroll on the “Herrengraben” along the town walls will take you back to the Middle Ages and to the days of lookouts, hangmen and executioners. Iphofen offers everything for unforgettable holidays in any season. Wine tasting and a variety of cultural events, historical sights and leisure time activities not only appeal to wine connoisseurs. -

Future Trends in Tourism

OFFICE OF TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT AT THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG Thomas Petermann Christoph Revermann Constanze Scherz Future trends in tourism Summary May 2005 Working report no. 101 SUMMARY Demographic, sociostructural and sociocultural developments have always led to changes in tourist demand and faced service providers in tourism with sub- stantial need to adjust. These constant challenges have expanded and intensified considerably in the first few years of the new millennium. War and tourism, extreme weather, the ongoing internationalisation of tourism and the ageing of society (increasingly prominent in public awareness) have emphatically demon- strated the latent vulnerability of tourism as a boom industry. The survival of the tourist industry depends decisively on recognising relevant trends and allowing for them in good time. In this context, TAB – at the initiative of the party working groups on the Com- mittee for Tourism – was commissioned by the Committee for Education, Re- search and Technology Assessment to carry out a TA project »Future trends in tourism«. Its focus was the themes »demographic change«, »EU expansion« and »security, crises and dangers«. The present report > identifies the relevant trends and their implications for tourism in Germany and by Germans, on the basis of a review and an analysis of current sociodemogra- phic data; > looks at the impacts of the eastward expansion of the EU and considers what trends in vacation traffic can be expected in and from the new EU nations and to and from Germany; > describes current and future potential dangers to tourism and discusses possibi- lities for improving information, prevention and crisis management. DEMOGRAPHICS The tourist industry is more than almost any other industry linked to its social and natural contexts. -

Vertreterwahl Am 14.10.2018 – Liste Der Gewählten Vertreter Und Ersatzvertreter

Vertreterwahl am 14.10.2018 – Liste der gewählten Vertreter und Ersatzvertreter Wahlbezirk Abtswind: Wahlbezirk Prosselsheim: Brügel Harald, Greuth Börger Birgit, Püssensheim Lenz Holger, Abtswind Friedrich Bernhard, Prosselsheim Schulz Jürgen, Abtswind Hauck Helga, Prosselsheim Schwanfelder Claudia, Abtswind Öchsner Richard, Prosselsheim Senft Oliver, Abtswind Weidt Winfried, Abtswind Zehnder Harald, Abtswind Wahlbezirk Rüdenhausen: Beck Peter, Wüstenfelden Wahlbezirk Escherndorf: Hüßner Hans, Wüstenfelden Klotz Stephan, Castell Pfrang Edith, Escherndorf Lindner Helmut, Rüdenhausen Sauer Christian, Escherndorf Nürnberger Jürgen, Rüdenhausen Sauer Michael, Köhler Pfeiffer Uwe, Rüdenhausen Schlick Matthias, Escherndorf Sinn Elfriede, Rüdenhausen Siedler Georg, Escherndorf Wahlbezirk Sommerach: Wahlbezirk Fahr: Drescher Andreas, Sommerach Henke Bruno, Sommerach Hart Karl, Volkach -Fahr Kallabis-Nüßlein Christiane, Sommerach Nikola Günther, Volkach-Fahr Karl Gerhard, Sommerach Östreicher Martina, Sommerach Pfaff Helmut, Sommerach Pickel Walter, Sommerach Wahlbezirk Kirchschönbach: Then Bernhard, Sommerach Then Max, Sommerach Rößner Albin, Kirchschönbach Weickert Ruppert, Sommerach Weiglein Leo, Geesdorf Wahlbezirk Stadelschwarzach: Wahlbezirk Lindach: Endres Mike, Lindach Ebert Martin, Järkendorf Gerlach Matthias, Stadelschwarzach Englert Holger, Lindach Krapf Roland, Stadelschwarzach Schön Joachim, Lindach Möhler Stefan, Laub Müller Gerd, Stadelschwarzach Weickert Klaus, Laub Wahlbezirk Nordheim: Braun Patrick, Nordheim Wahlbezirk Stammheim: -

M I T T E I L U N G S B L A

MM ii tt tt ee ii ll uu nn gg ss bb ll aa tt tt der Verwaltungsgemeinschaft Großlangheim Amtsstunden der Verwaltungsgemeinschaft: Großlangheim: Montag bis Freitag von 08:00 Uhr bis 12:00 Uhr Telefon: (0 93 25) 97 32 – 0 sowie Donnerstag von 14:00 Uhr bis 18:00 Uhr Telefax: (0 93 25) 97 32 – 40 E-Mail: [email protected] Sprechstunden der Bürgermeister der Mitgliedsgemeinden: Kleinlangheim: Montag und Mittwoch von 16:00 Uhr bis 18:00 Uhr Telefon: (0 93 25) 2 77 Telefax: (0 93 25) 2 77 Wiesenbronn: Dienstag von 18:00 Uhr bis 19:30 Uhr Telefon: (0 93 25) 9 99 66 o. 0171/2877899 Donnerstag von 18:00 Uhr bis 20:00 Uhr Telefax: (0 93 25) 9 99 89 Weitere wichtige Telefonnummern: Polizei: 1 10 Rettungsdienst: 1 12 Feuerwehr: 1 12 Ärztl. Bereitschaftsdienst: (0 18 05) 19 12 12 Dieses Mitteilungsblatt gilt nicht als Amtsblatt. Satzungen und Verordnungen werden durch Niederlegung in der Geschäftsstelle der Verwaltungsgemeinschaft und durch Hinweise an den Amtstafeln amtlich bekannt gemacht. Die Verteilung erfolgt kostenlos an alle Haushalte. A p r i l 2 0 1 1 Bekanntmachung über die Schulanmeldung für das Jedes Schulkind muss die Volksschule besuchen, in Schuljahr 2011/2012 deren Sprengel es wohnt. Zum Sprengel unserer Schule gehören die Gemeinden Kleinlangheim mit Die Schulanmeldung für das Schuljahr 2011/12 findet Ortsteilen, Großlangheim und Wiesenbronn. am Donnerstag, 07. April um 14:00 Uhr für alle Schul- neulinge im Schulhaus Großlangheim statt. Die Erziehungsberechtigten sollten persönlich mit dem Kind zur Schulanmeldung kommen oder im Anzumelden sind alle Kinder, die bis zum 30.09.2011 Verhinderungsfall einen Vertreter beauftragen. -

Rebuilding the Soul: Churches and Religion in Bavaria, 1945-1960

REBUILDING THE SOUL: CHURCHES AND RELIGION IN BAVARIA, 1945-1960 _________________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _________________________________________________ by JOEL DAVIS Dr. Jonathan Sperber, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2007 © Copyright by Joel Davis 2007 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled REBUILDING THE SOUL: CHURCHES AND RELIGION IN BAVARIA, 1945-1960 presented by Joel Davis, a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. __________________________________ Prof. Jonathan Sperber __________________________________ Prof. John Frymire __________________________________ Prof. Richard Bienvenu __________________________________ Prof. John Wigger __________________________________ Prof. Roger Cook ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe thanks to a number of individuals and institutions whose help, guidance, support, and friendship made the research and writing of this dissertation possible. Two grants from the German Academic Exchange Service allowed me to spend considerable time in Germany. The first enabled me to attend a summer seminar at the Universität Regensburg. This experience greatly improved my German language skills and kindled my deep love of Bavaria. The second allowed me to spend a year in various archives throughout Bavaria collecting the raw material that serves as the basis for this dissertation. For this support, I am eternally grateful. The generosity of the German Academic Exchange Service is matched only by that of the German Historical Institute. The GHI funded two short-term trips to Germany that proved critically important. -

Familien Fragebogen

Familien Fragebogen Diese Befragung wird zur Erstellung der ersten Kinder- und Familien-Freizeitkarte für unsere Region am Bayerischen Untermain durchgeführt. Die Ergebnisse kommen als Freizeittipps in den Plan. Bitte die ganze Familie gemeinsam ausfüllen. Wir wohnen in der Stadt/Gemeinde: ____________________________________ 1. Der beste Spielplatz in unserer Gegend (im Ort oder Umgebung) ist… __________________________________________________ (Ort/Ortsteil + Straße) Begründung: _________________________________________________________ Der zweitbeste Spielplatz in unserer Gegend (im Ort oder Umgebung) ist… __________________________________________________ (Ort/Ortsteil + Straße) Begründung: _________________________________________________________ 2. Außer auf offiziellen Spielplätzen spielen wir gerne dort...(Bitte genaue Ortsan- gabe und auf der beigefügten Karte markieren - am besten mit Nummer versehen) Wiese zum Drachensteigen: ____________________________________________ Wiese zum (Ball)spielen: _______________________________________________ Picknick-Wiese: ______________________________________________________ Rodelhang: __________________________________________________________ Wassertreffpunkt (bespielbare Brunnen, Bäche…): ___________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ Skaten: _____________________________________________________________ Spielort im Wald: _____________________________________________________ -

Würzburg Residence with the Court Gardens and Residence Square

WHC Nomination Documentation File name: 169.pdf UNESCO Region EUROPE SITE NAME (and NUMBER) ("TITLE") Würzburg Residence with the Court Gardens and Residence Square DATE OF INSCRIPTION ("SUBJECT") 30/10/1981 STATE PARTY ("AUTHOR") GERMANY CRITERIA ("KEY WORDS") C (i)(iv) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: The Committee made no statement BRIEF DESCRIPTION: Under the patronage of two successive bishop-princes, this sumptuous Baroque palace, one of the largest and most beautiful in Germany, surrounded by magnificent gardens, was built and decoreted in the 18th century by an international corps of architects, painters (including Tiepolo), sculptors and stucco workers, led by Balthasar Neumann. 1.b. State, province or region: Land of Bavaria Administrative District : Lower Franconia City of Würzburg 1.d Exact location: Longitude 9°56'23" East Latitude 49°47'23" North Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Kunst G:\StMWFK\Abteilungen\Abteilung B\Referat B_4\Referatsordner\Welterbe\Würzburg\WHC Nachlieferung Pufferzone 9119 r.doc ENTWURF Datum: 30.03.2010 Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Kunst, 80327 München B4 Entwurf erstellt/geprüft: Albert_F UNESCO World Heritage Centre Reinschrift erstellt/geprüft: Director M. Francesco Bandarin Reinschrift geprüft durch Entwurfsverfasser: 7, place de Fontenoy F-75352 Paris 07 FP Reinschrift versandt: Frankreich Reinschrift gefaxt: Reinschrift an e-mail: Ihr Zeichen / Ihre Nachricht vom Unser Zeichen (bitte bei Antwort angeben) München, 30.03.2010 I WHC/74/2442/DE/PA/JSW B4-K0112.1.9-12 a/9 119 Telefon: 089 2186 2511 01.03.2010 Name: Herr Albert “Würzburg Residence with the Court Gardens and Residence Square” (Ref. 169) here: Minor boundary modification proposal Attachments: 2 copies of the map 2 CD-ROMs Dear Mr. -

Roab ~Ap ~Unb Unb ~Latt a Newsletter About the German Colony Establish~D at Broad Bay, Maine 1740 - 1753 II Volume 2 July/Aug 1993 Number 411

®lb ~roab ~ap ~unb unb ~latt A Newsletter about the German Colony Establish~d at Broad Bay, Maine 1740 - 1753 II Volume 2 July/Aug 1993 Number 411 The old German Lutheran Church in Waldoboro, a designated Historic Landmark, once the happy scene of religious and family activities for many of our ancestors, reverberated once again with songs, sermons, prayers and laughter as over 100 descendants of those hardy Germans met for the first time in an official capacity and inaugurated the Old Broad Bay Family History Projects on 1 Aug 1993. The German Protestant Society, which takes such good care of this magnificent old building, and the Ladies Auxiliary, President Becky Maxwell, opened the building, and their hearts, for our use. We wish to thank Becky and those fine women who baked their way into our hearts for such a kind reception. Thank you, also, to the German Protestant Society for their many kindnesses to us . Richard Castner gives a report in this issue of the business .1eeting we held. It was thrilling to sit in those old pews and imagine our German ancestors hovering, just over head, just out of sight, and approving of our activities that day! Thank you all for a great weekend. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you . Official Publication of Old Broad Bay Family History Projects Subscriptions to Bund und Blatt ~ It was rather disconcerting to add everything up and discover that only 54 out of over 220 on our mailing list have been contributing financially to our project. Now, 25% response is not very good. -

Frankfurtrhinemain in Figures 2019

European Institutions European Central Bank (ECB) European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) European Meteorological Satellite Organisation (EUMETSAT) European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) Tourism in FrankfurtRhineMain No. of hotels and guest houses 2,887 FrankfurtRhineMain No. of beds 165,548 Total guests 12,936,055 Guests from abroad in percent 29.2 % Total overnight stays 26,123,146 Average duration of stay 2.0 days in figures 2019 Figures per: 2017 Transport Infrastructure FrankfurtRhineMain Total of classified roads 11,420 km including Federal highways (Bundesautobahnen) 1,448 km Long distance stations 18 Ports along the rivers Rhine and Main 7 Figures per: 01.01.2018 FrankfurtRhineMain In the RhineMain region 7.9 % of the German gross value is generated. The Hessian part of the region realises Frankfurt International Airport (FRA) a staggering 78 % of the gross domestic product of the federal state of Hessian. These numbers emphasise the status of FrankfurtRhineMain as – according to European standards – one of the most important metropolitan FRA segment within Frankfurt International All German areas of Germany. German airports Airport Airports in percent There is also no lack of international flair: four European institutions are based in the region. More than 2,500 companies from China and the United States alone have settled here. This is not least due to the excellent inf- No. of passengers 64,500,386 27.4 % 235,175,472 rastructure of the region. At 12 international schools, students can obtain an internationally accredited degree. Freight (+Airmail) volume in tons 2,228,969 44.7 % 4,983,656 With over 1,300 flight movements a day, Frankfurt International Airport contributes much to the outstanding accessibility of the metropolitan area for both business travellers and tourists.