Differentiability Versus Continuity: Restriction and Extension Theorems and Monstrous Examples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics David Aubin, Catherine Goldstein

Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics David Aubin, Catherine Goldstein To cite this version: David Aubin, Catherine Goldstein. Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics. 2013. hal- 00830121v1 HAL Id: hal-00830121 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-00830121v1 Preprint submitted on 4 Jun 2013 (v1), last revised 8 Jul 2014 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics David Aubin and Catherine Goldstein Abstract. In the historical literature, opposite conclusions were drawn about the impact of the First World War on mathematics. In this chapter, the case is made that the war was an important event for the history of mathematics. We show that although mathematicians' experience of the war was extremely varied, its impact was decisive on the life of a great number of them. We present an overview of some uses of mathematics in war and of the development of mathematics during the war. We conclude by arguing that the war also was a crucial factor in the institutional modernization of mathematics. Les vrais adversaires, dans la guerre d'aujourd'hui, ce sont les professeurs de math´ematiques`aleur table, les physiciens et les chimistes dans leur laboratoire. -

Theological Metaphors in Mathematics

STUDIES IN LOGIC, GRAMMAR AND RHETORIC 44 (57) 2016 DOI: 10.1515/slgr-2016-0002 Stanisław Krajewski University of Warsaw THEOLOGICAL METAPHORS IN MATHEMATICS Abstract. Examples of possible theological influences upon the development of mathematics are indicated. The best known connection can be found in the realm of infinite sets treated by us as known or graspable, which constitutes a divine-like approach. Also the move to treat infinite processes as if they were one finished object that can be identified with its limits is routine in mathemati- cians, but refers to seemingly super-human power. For centuries this was seen as wrong and even today some philosophers, for example Brian Rotman, talk critically about “theological mathematics”. Theological metaphors, like “God’s view”, are used even by contemporary mathematicians. While rarely appearing in official texts they are rather easily invoked in “the kitchen of mathemat- ics”. There exist theories developing without the assumption of actual infinity the tools of classical mathematics needed for applications (For instance, My- cielski’s approach). Conclusion: mathematics could have developed in another way. Finally, several specific examples of historical situations are mentioned where, according to some authors, direct theological input into mathematics appeared: the possibility of the ritual genesis of arithmetic and geometry, the importance of the Indian religious background for the emergence of zero, the genesis of the theories of Cantor and Brouwer, the role of Name-worshipping for the research of the Moscow school of topology. Neither these examples nor the previous illustrations of theological metaphors provide a certain proof that religion or theology was directly influencing the development of mathematical ideas. -

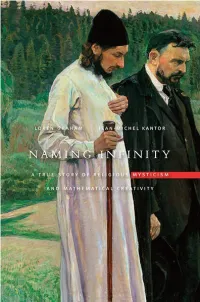

Naming Infinity: a True Story of Religious Mysticism And

Naming Infinity Naming Infinity A True Story of Religious Mysticism and Mathematical Creativity Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Graham, Loren R. Naming infinity : a true story of religious mysticism and mathematical creativity / Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-03293-4 (alk. paper) 1. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Religious aspects. 2. Mysticism—Russia (Federation) 3. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Philosophy. 4. Mathematics—France—Religious aspects. 5. Mathematics—France—Philosophy. 6. Set theory. I. Kantor, Jean-Michel. II. Title. QA27.R8G73 2009 510.947′0904—dc22â 2008041334 CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Storming a Monastery 7 2. A Crisis in Mathematics 19 3. The French Trio: Borel, Lebesgue, Baire 33 4. The Russian Trio: Egorov, Luzin, Florensky 66 5. Russian Mathematics and Mysticism 91 6. The Legendary Lusitania 101 7. Fates of the Russian Trio 125 8. Lusitania and After 162 9. The Human in Mathematics, Then and Now 188 Appendix: Luzin’s Personal Archives 205 Notes 212 Acknowledgments 228 Index 231 ILLUSTRATIONS Framed photos of Dmitri Egorov and Pavel Florensky. Photographed by Loren Graham in the basement of the Church of St. Tatiana the Martyr, 2004. 4 Monastery of St. Pantaleimon, Mt. Athos, Greece. 8 Larger and larger circles with segment approaching straight line, as suggested by Nicholas of Cusa. 25 Cantor ternary set. -

CALCULUS I §2.2: Differentiability, Graphs, and Higher Derivatives

MATH 12002 - CALCULUS I x2.2: Differentiability, Graphs, and Higher Derivatives Professor Donald L. White Department of Mathematical Sciences Kent State University D.L. White (Kent State University) 1 / 10 Differentiability The process of finding a derivative is called differentiation, and we define: Definition Let y = f (x) be a function and let a be a number. We say f is differentiable at x = a if f 0(a) exists. What does this mean in terms of the graph of f ? If f 0(a) = lim f (a+h)−f (a) exists, then f (a) must be defined. h!0 h Since the denominator is approaching 0, in order for the limit to exist, the numerator must also approach 0; that is, lim (f (a + h) − f (a)) = 0: h!0 Hence lim f (a + h) = f (a), and so lim f (x) = f (a), h!0 x!a meaning f must be continuous at x = a. D.L. White (Kent State University) 2 / 10 Differentiability But being continuous at a is not enough to make f differentiable at a. Differentiability is \continuity plus." The \plus" is smoothness: the graph cannot have a sharp \corner" at a. The graph also cannot have a vertical tangent line at x = a: the slope of a vertical line is not a real number. Hence, in order for f to be differentiable at a, the graph of f must 1 be continuous at a, 2 be smooth at a, i.e., no sharp corners, and 3 not have a vertical tangent line at x = a. -

Example: Using the Grid Provided, Graph the Function

3.2 Differentiability Calculus 3.2 DIFFERENTIABILITY Notecards from Section 3.2: Where does a derivative NOT exist, Definition of a derivative (3rd way). The focus on this section is to determine when a function fails to have a derivative. For all you non-English majors, the word differentiable means you are able to take a derivative, or the derivative exists. Example 1: Using the grid provided, graph the function fx( ) = x − 3 . y a) What is fx'( ) as x → 3− ? b) What is fx'( ) as x → 3+ ? c) Is f continuous at x = 3? d) Is f differentiable at x = 3? x 2 Example 2: Graph fx x3 y a) Describe the derivative of f (x) as x approaches 0 from the left and the right. 2 b) Suppose you found fx' . 33 x x What is the value of the derivative when x = 0? 3 Example 3: Graph fx x y a) Describe the derivative of f (x) as x approaches 0 from the left and the right. 1 b) Suppose you found fx' . 33 x2 What is the value of the derivative when x = 0? x These last three examples (along with any graph that is not continuous) are NOT differentiable. The first graph had a “corner” or a sharp turn and the derivatives from the left and right did not match. The second graph had a “cusp” where secant line slope approach positive infinity from one side and negative infinity from the other. The third graph had a “vertical tangent line” where the secant line slopes approach positive or negative infinity from both sides. -

Figure 1: Finding a Tangent Plane to a Graph

Figure 1: Finding a tangent plane to a graph Math 8 Winter 2020 Tangent Approximations and Differentiability We have seen how to find partial derivatives of functions from R2 to R, and seen how to use them to find tangent planes to graphs. Figure 1 shows the graph of the function f(x; y) = x2 + y2. The two red curves are the intersections of the graph with planes x = x0 and y = y0, and the yellow lines are tangent lines to the red curves, also lying in those planes. The slopes of the yellow lines (vertical rise over horizontal run, where the z- axis is vertical) are the partial derivatives of f at the point (x; y) = (x0; y0). The plane containing those yellow lines should be tangent to the graph of f. The phrase should be is important here. So far, we have pretty much been assuming this works. There is a very good argument that if there is any plane tangent to this graph at this point, it must be the plane containing these yellow lines, because those lines are tangent to the graph. But how do we know there is any tangent plane at all? 1 2xy Figure 2: Graph of f(x; y) = . px2 + y2 If (x; y) = (r sin θ; r cos θ), then f(x; y) = r sin(2θ). It turns out that a function can have partial derivatives without its graph having a tangent plane. Here is an example. Figure 2 shows two different pictures of a portion of the graph of the function 2xy f(x; y) = : px2 + y2 The x- and y-axes are drawn in red, and the intersection of the graph with the vertical plane y = x is drawn in yellow. -

Is Differentiable at X=A Means F '(A) Exists. If the Derivative

The Derivative as a Function Differentiable: A function, f(x), is differentiable at x=a means f '(a) exists. If the derivative exists on an interval, that is , if f is differentiable at every point in the interval, then the derivative is a function on that interval. f ( x h ) f ( x ) Definition: f ' ( x ) lim . h 0 h ( x h ) 2 x 2 x 2 2 xh h 2 x 2 Example: f ( x ) x 2 f ' ( x ) lim lim lim (2 x h ) 2 x h 0 h h 0 h h 0 Exercise: Show the derivative of a line is the slope of the line. That is, show (mx + b)' = m The derivative of a constant is 0. Linear Rule: If A and B are numbers and if f '(x) and g '(x) both exist then the derivative of Af+Bg at x is Af '(x) + Bg '(x). That is (Af + Bg)'(x)= Af '(x) + Bg '(x) Applying the linear rule for derivatives, we can differentiate any quadratic. Example: g ( x ) 4 x 2 6 x 7 g ' ( x ) 4(2 x ) 6 8 x 6 We can find the tangent line to g at a given point. Example: For g(x) as above, find the equation of the tangent line at (2, g(2)). g(2)=4(4)-12+7= 11 so the point of tangency is (2, 11). To get the slope, we plug x=2 into g '(x)=8x-6 the slope is g'(2)= 8(2)-6=10 so the tangent line is y = 10(x - 2) + 11 Notations for the derivative: df df f ' ( x ) f ' (a ) dx dx x a If a function is differentiable at x=a then it must be continuous at a. -

Unit #5 - Implicit Differentiation, Related Rates

Unit #5 - Implicit Differentiation, Related Rates Some problems and solutions selected or adapted from Hughes-Hallett Calculus. Implicit Differentiation 1. Consider the graph implied by the equation (c) Setting the y value in both equations equal to xy2 = 1. each other and solving to find the intersection point, the only solution is x = 0 and y = 0, so What is the equation of the line through ( 1 ; 2) 4 the two normal lines will intersect at the origin, which is also tangent to the graph? (x; y) = (0; 0). Differentiating both sides with respect to x, Solving process: dy 3 3 y2 + x 2y = 0 (x − 4) + 3 = − (x − 4) − 3 dx 4 4 3 3 so x − 3 + 3 = − x + 3 − 3 4 4 dy −y2 3 3 = x = − x dx 2xy 4 4 6 x = 0 4 dy At the point ( 1 ; 2), = −4, so we can use the x = 0 4 dx point/slope formula to obtain the tangent line y = −4(x − 1=4) + 2 Subbing back into either equation to find y, e.g. y = 3 (0 − 4) + 3 = −3 + 3 = 0. 2. Consider the circle defined by x2 + y2 = 25 4 3. Calculate the derivative of y with respect to x, (a) Find the equations of the tangent lines to given that the circle where x = 4. (b) Find the equations of the normal lines to x4y + 4xy4 = x + y this circle at the same points. (The normal line is perpendicular to the tangent line.) Let x4y + 4xy4 = x + y. Then (c) At what point do the two normal lines in- dy dy dy 4x3y + x4 + (4x) 4y3 + 4y4 = 1 + tersect? dx dx dx hence Differentiating both sides, dy 4yx3 + 4y4 − 1 = : dx 1 − x4 − 16xy3 d d x2 + y2 = (25) dx dx 4. -

Limit Definition of the Derivative

Limit Definition of the Derivative We define the derivative of a function f(x) at x = x0 as 0 f(x0 + h) − f(x0) 0 f(z) − f(x0) f (x0) = lim or f (x0) = lim h!0 h z!x0 z − x0 if these limits exist! We'll usually find the derivative as a function of x and then plug in x = a. (This allows us to quickly find the value of the derivative a multiple values of a without having to evaluate a limit for each of them.) f(x + h) − f(x) f(z) − f(x) f 0(x) = lim or f 0(x) = lim h!0 h z!x z − x (The book also defines left- and right-hand derivatives in a manner analogous to left- and right-hand limits or continuity.) Notation and Higher Order Derivatives The following are all different ways of writing the derivative of a function y = f(x): d df dy · f 0(x); y0; [f(x)] ; ; ;D [f(x)] ;D [f(x)] ; f dx dx dx x (The brackets in the third, sixth, and seventh forms may be changed to parentheses or omitted entirely.) If we take the derivative of the derivative we get the second derivative. We can also find other higher order derivatives (third, fourth, fifth, etc.). The notation for these is as follows: Order Notation d2 d2f d2y ·· Second f 00(x); y00; f(x); ; ;D2f(x);D2f(x); f dx2 dx2 dx2 x 3 3 3 d d f d y ) Third f 000(x); y000; f(x); ; ;D3f(x);D3f(x); f dx3 dx3 dx3 x d4 d4f d4y Fourth f (4)(x); y(4); f(x); ; ;D4f(x);D4f(x) dx4 dx4 dx4 x dn dnf dny nth f (n)(x); y(n); f(x); ; ;Dnf(x);Dnf(x) dxn dxn dxn x When is a Function Not Differentiable? There is a theorem relating differentiability and continuity which says that if a function is differentiable at a point then it is also continuous there. -

Science and Nation After Socialism in the Novosibirsk Scientific Center, Russia

Local Science, Global Knowledge: Science and Nation after Socialism in the Novosibirsk Scientific Center, Russia Amy Lynn Ninetto Mohnton, Pennsylvania B.A., Franklin and Marshall College, 1993 M.A., University of Virginia, 1997 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dcpartmcn1 of Anthropology University of Virginia May 2002 11 © Copyright by Amy Lynn Ninetta All Rights Reserved May 2002 lll Abstract This dissertation explores the changing relationships between science, the state, and global capital in the Novosibirsk Scientific Center (Akademgorodok). Since the collapse of the state-sponsored Soviet "big science" establishment, Russian scientists have been engaging transnational flows of capital, knowledge, and people. While some have permanently emigrated from Russia, others travel abroad on temporary contracts; still others work for foreign firms in their home laboratories. As they participate in these transnational movements, Akademgorodok scientists confront a number of apparent contradictions. On one hand, their transnational movement is, in many respects, seen as a return to the "natural" state of science-a reintegration of former Soviet scientists into a "world science" characterized by open exchange of information and transcendence of local cultural models of reality. On the other hand, scientists' border-crossing has made them-and the state that claims them as its national resources-increasingly conscious of the borders that divide world science into national and local scientific communities with differential access to resources, prestige, and knowledge. While scientists assert a specifically Russian way of doing science, grounded in the historical relationships between Russian science and the state, they are reaching sometimes uneasy accommodations with the globalization of scientific knowledge production. -

Differential Calculus – Definitions, Rules and Theorems Sarah Brewer, Alabama School of Math and Science

Differential Calculus – Definitions, Rules and Theorems Sarah Brewer, Alabama School of Math and Science Precalculus Review Functions, Domain and Range : a function from to assigns to each a unique the domain of is the set - the set of all real numbers for which the function is defined 푓 푋 → 푌 푓 푋 푌 푥 ∈ 푋 푦 ∈ 푌 is the image of under , denoted ( ) 푓 푋 the range of is the subset of consisting of all images of numbers in 푌 푥 푓 푓 푥 is the independent variable, is the dependent variable 푓 푌 푋 is one-to-one if to each -value in the range there corresponds exactly one -value in the domain 푥 푦 is onto if its range consists of all of 푓 푦 푥 푓Implicit v. Explicit Form 푌 3 + 4 = 8 implicitly defines in terms of = + 2 explicit form 푥 푦 푦 푥 3 푦Graphs− 4 o푥f Functions A function must pass the vertical line test A one-to-one function must also pass the horizontal line test Given the graph of a basic function = ( ), the graph of the transformed function, = ( + ) + = + + 푦 푓 푥, can be found using the following rules: 푐 - vertical stretch (mult. -values by ) 푦 푎푓 푏푥 푐 푑 푎푓 �푏 �푥 푏�� 푑 - horizontal stretch (divide -values by ) 푎 푦 푎 – horizontal shift (shift left if > 0, right if < 0) 푏푐 푥 푐 푏 푐 > 0 < 0 푏 - vertical shift (shift up if 푏 , down if 푏 ) You푑 should know the basic 푑graphs of: 푑 = , = , = , = | |, = , = , = , 3 1 = sin , =2 cos , 3 = tan , = csc , = sec , = cot 푦 푥 푦 푥 푦 푥 푦 푥 푦 √푥 푦 √푥 푦 푥 For푦 further푥 discussion푦 푥 of 푦graphing,푥 see푦 Precal 푥and푦 Trig Guides푥 푦 to Graphing푥 Elementary Functions Algebraic functions (polynomial, radical, rational) - functions that can be expressed as a finite number of sums, differences, multiples, quotients, & radicals involving Functions that are not algebraic are trancendental (eg. -

![Arxiv:1710.05659V1 [Math.HO]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9212/arxiv-1710-05659v1-math-ho-3119212.webp)

Arxiv:1710.05659V1 [Math.HO]

FROM POLAND TO PETERSBURG: THE BANACH-TARSKI PARADOX IN BELY’S MODERNIST NOVEL NOAH GIANSIRACUSA∗ AND ANASTASIA VASILYEVA∗∗ ABSTRACT. Andrei Bely’s novel Petersburg, first published in 1913, was declared by Vladimir Nabokov one of the four greatest masterpieces of 20th-century prose. The Banach-Tarski Paradox, published in 1924, is one of the most striking and well-known results in 20th-century mathematics. In this paper we explore a potential connection between these two landmark works, based on various interactions with the Moscow Mathematical School and passages in the novel itself. 1. INTRODUCTION Andrei Bely (1880-1934) was a poet, novelist, and theoretician who helped lead the Symbolist movement in Russia in the early 20th century. His most regarded work is the modernist novel Petersburg, published serially in 1913-1914 then in a revised and shortened form in 1922. Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977) famously declared Petersburg one of the four greatest works of prose of the 20th century, along with Joyce’s Ulysses, Kafka’s Metamorphosis, and Proust’s A` la recherche du temps perdu. As with these three other works, the scholarly literature on Petersburg is vast and continues to grow; for instance, a volume of essays on Petersburg celebrating its centennial was just released [Coo17]. An emerging direction of scholarship has been to better understand the origins and meaning of the remarkably frequent mathematical imagery in Petersburg [Szi02, Szi11, GK09, Sve13, Kos13, GV17]. That Bely had an interest in math is not surprising: his father was the influential math- ematician Nikolai Bugaev1 (1837-1903) who is credited with creating the Moscow Mathemat- ical School, one of the most active and successful groups of mathematicians in recent history [Dem14, DTT15].