Physics Moves to the Provinces: the Siberian Physics Community and Soviet Power, 1917–1940

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boris Hessen: Physics and Philosophy in the Soviet Union, 1927–1931 Neglected Debates on Emergence and Reduction Series: History of Physics

springer.com Chris Talbot, Olga Pattison (Eds.) Boris Hessen: Physics and Philosophy in the Soviet Union, 1927–1931 Neglected Debates on Emergence and Reduction Series: History of Physics Presents key works by the outstanding Soviet philosopher of science Boris Hessen, available in English for the first time Revives important ideas that were lost after the author's execution by Stalin in 1936 Adds essential new perspectives to current debates on emergence This book presents key works of Boris Hessen, outstanding Soviet philosopher of science, 1st ed. 2021, IX, 169 p. 7 illus., 1 illus. in available here in English for the first time. Quality translations are accompanied by an editors' color. introduction and annotations. Boris Hessen is known in history of science circles for his “Social and Economic Roots of Newton’s Principia” presented in London (1931), which inspired new Printed book approaches in the West. As a philosopher and a physicist, he was tasked with developing a Hardcover Marxist approach to science in the 1920s. He studied the history of physics to clarify issues 119,99 € | £109.99 | $149.99 such as reductionism and causality as they applied to new developments. With the [1] 128,39 € (D) | 131,99 € (A) | CHF philosophers called the “Dialecticians”, his debates with the opposing “Mechanists” on the issue 141,50 of emergence are still worth studying and largely ignored in the many recent works on this eBook subject. Taken as a whole, the book is a goldmine of insights into both the foundations of 96,29 € | £87.50 | $109.00 physics and Soviet history. -

Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics David Aubin, Catherine Goldstein

Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics David Aubin, Catherine Goldstein To cite this version: David Aubin, Catherine Goldstein. Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics. 2013. hal- 00830121v1 HAL Id: hal-00830121 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-00830121v1 Preprint submitted on 4 Jun 2013 (v1), last revised 8 Jul 2014 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics David Aubin and Catherine Goldstein Abstract. In the historical literature, opposite conclusions were drawn about the impact of the First World War on mathematics. In this chapter, the case is made that the war was an important event for the history of mathematics. We show that although mathematicians' experience of the war was extremely varied, its impact was decisive on the life of a great number of them. We present an overview of some uses of mathematics in war and of the development of mathematics during the war. We conclude by arguing that the war also was a crucial factor in the institutional modernization of mathematics. Les vrais adversaires, dans la guerre d'aujourd'hui, ce sont les professeurs de math´ematiques`aleur table, les physiciens et les chimistes dans leur laboratoire. -

Theological Metaphors in Mathematics

STUDIES IN LOGIC, GRAMMAR AND RHETORIC 44 (57) 2016 DOI: 10.1515/slgr-2016-0002 Stanisław Krajewski University of Warsaw THEOLOGICAL METAPHORS IN MATHEMATICS Abstract. Examples of possible theological influences upon the development of mathematics are indicated. The best known connection can be found in the realm of infinite sets treated by us as known or graspable, which constitutes a divine-like approach. Also the move to treat infinite processes as if they were one finished object that can be identified with its limits is routine in mathemati- cians, but refers to seemingly super-human power. For centuries this was seen as wrong and even today some philosophers, for example Brian Rotman, talk critically about “theological mathematics”. Theological metaphors, like “God’s view”, are used even by contemporary mathematicians. While rarely appearing in official texts they are rather easily invoked in “the kitchen of mathemat- ics”. There exist theories developing without the assumption of actual infinity the tools of classical mathematics needed for applications (For instance, My- cielski’s approach). Conclusion: mathematics could have developed in another way. Finally, several specific examples of historical situations are mentioned where, according to some authors, direct theological input into mathematics appeared: the possibility of the ritual genesis of arithmetic and geometry, the importance of the Indian religious background for the emergence of zero, the genesis of the theories of Cantor and Brouwer, the role of Name-worshipping for the research of the Moscow school of topology. Neither these examples nor the previous illustrations of theological metaphors provide a certain proof that religion or theology was directly influencing the development of mathematical ideas. -

Hungarian Refugee Scientists in Defense of the Autonomy

THE INTERCONNECTEDNESS OF THE SOCIAL AND NATURAL SCIENCES: HUNGARIAN REFUGEE SCIENTISTS IN DEFENSE OF THE AUTONOMY OF SCIENCE By Csaba Olasz Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts CEU eTD Collection Supervisor: Professor Karl Hall Second reader: Professor Emese Lafferton Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, maybe made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection i ABSTRACT The contribution of foreign born scientists to the building of the first Atomic bomb is well-known. That a number of theoretical physicist involved in the Manhattan Project continued taking an active part in the politicization of nuclear physics of post war America were also refugees is, perhaps, less so. This essay considers the public engagement of Hungarian born scientists in a broader historical context that has shaped their professional trajectories. Discussing themes as family backgrounds, (forced?) migration, totalitarian systems, personal ambitions, technical brilliance, socio-economic relations of science and government as well as nuclear defense politics, I point out that my protagonists have become agencies in and of the transformation that science politics had been undergoing at the time. The shared experience as Atomic scientists of Eugene Wigner and Leo Szilard is the departure point from which an analysis of personal and socio-political factors is used to interpret any discrepancies in the rationale behind, and the nature of, their public engagement. -

Soviet States and Beyond: Political Epistemologies Of/And Marxism 1917-1945-1968

Soviet States and Beyond: Political Epistemologies of/and Marxism 1917-1945-1968 21-22 June 2018, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Myasnickaya 20, Moscow Самойлов Д.,Ефимович Б., Дворец техники. 1933 Organized by FRIEDRICH CAIN Max Weber Centre for Advanced Cultural and Social Studies, University of Erfurt ALEXANDER DMITRIEV Poletayev Institute for Theoretical and Historical Studies in the Humanities National Research University Higher School of Economics (IGITI HSE), Moscow DIETLIND HÜCHTKER Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe (GWZO), Leipzig JAN SURMAN IGITI HSE Thurdsay, 21 June 2018, Myasnickaya 20, aud. 311 10:00-10:30 Opening 10:30-12:00 Soviet Science Studies and Their Politics (Chair Dietlind Hüchtker) ALEXANDER DMITRIEV, IGITI HSE: Beyond Boris Hessen: New History and Philosophy of Science in Early Soviet Union IGOR KAUFMANN, ST. PETERSBURG STATE UNIVERSITY: Epistemic Programme(s) of the Soviet Science Studies: something old, something new, something bizarre 12:00-13:00 Lunch Break 13:00-14:30 Entanglements & Receptions I: Before WWII (Chair Friedrich Cain) DARIA DROZDOVA, SCHOOL OF PHILOSOPHY, HSE: Historicizing Science: Soviet and Italian Interwar Projects in Comparison KARL HALL, CENTRAL EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY, BUDAPEST: Sarton’s Rivals: Disciplinary Dilemmas of History of Science circa 1931 14:30-15:00 Coffee Break 15:00-16:30 Soviet Science (Studies) in Comparison (Chair Daria Petushkova) GEERT SOMSEN, MAASTRICHT UNIVERSITY: The Epistemology of Popularization: British ‘Scientific -

The Social and Economic Roots of the Scientific Revolution

THE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC ROOTS OF THE SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION Texts by Boris Hessen and Henryk Grossmann edited by GIDEON FREUDENTHAL PETER MCLAUGHLIN 13 Editors Preface Gideon Freudenthal Peter McLaughlin Tel Aviv University University of Heidelberg The Cohn Institute for the History Philosophy Department and Philosophy of Science and Ideas Schulgasse 6 Ramat Aviv 69117 Heidelberg 69 978 Tel Aviv Germany Israel The texts of Boris Hessen and Henryk Grossmann assembled in this volume are important contributions to the historiography of the Scientific Revolution and to the methodology of the historiography of science. They are of course also historical documents, not only testifying to Marxist discourse of the time but also illustrating typical European fates in the first half of the twentieth century. Hessen was born a Jewish subject of the Russian Czar in the Ukraine, participated in the October Revolution and was executed in the Soviet Union at the beginning of the purges. Grossmann was born a Jewish subject of the Austro-Hungarian Kaiser in Poland and served as an Austrian officer in the First World War; afterwards he was forced to return to Poland and then because of his revolutionary political activities to emigrate to Germany; with the rise to power of the Nazis he had to flee to France and then America while his family, which remained in Europe, perished in Nazi concentration camps. Our own acquaintance with the work of these two authors is also indebted to historical context (under incomparably more fortunate circumstances): the revival of Marxist scholarship in Europe in the wake of the student movement and the pro- fessionalization of history of science on the Continent. -

Supplementvolum-E18 Nu-Mber-41989 .__L,___Society

ISSN 0739-4934 NEWSLETTER I IISTORY OF SCIENCE SUPPLEMENTVOLUM-E18 NU-MBER-41989 .__L,___SOCIETY - WELCOME TO GAINESVILLE HSS EXECUTIVE BY FREDERICK GREGORY COMMITTEE "A SOPI-llSTICATED SLICE of small-town south": so wrote Jonathan Lerner PRESIDENT about Gainesville for Washington Post readers this past spring. Like the majority MARY JO NYE, University of Oklahoma of visitors to Gainesville, Lerner was impressed with the topography of the city, VICE-PRESIDENT which forms a hammock-a dry area, relatively higher than its surroundings, STEPHEN G. BRUSH, University of Maryland that can support hardwood trees. Residents of Gainesville are enormously proud of the extensive canopy that covers 46 percent of their town, the highest per EXECUTIVE SECRETARY MICHAEL M. SOKAL, Worcester centage of any Florida city. In addition to the majestic live oaks, the southern Polytechnic Institute pine, and a variety of palm trees, dogwoods and magnolias are also plentiful. TREASURER Unfortunately the HSS Annual Meeting is held at a time of year that misses the MARY LOUISE GLEASON, New York City blossoms of our giant azaleas, some older ones of which are as high as roof tops. EDITOR f obvious interest to historians of science is nearby Paynes Prairie, an 18,000- RONALD L. NUMBERS, University of acre wildlife preserve whose zoological and botanical life was described in vivid Wisconsin-Madison detail by William Bartram after his travels through the region in 1774. Meeting sessions will be held on the campus of the University of Florida, which, at least in this part of the country, is never to be mixed up with Florida State University in Tallahassee. -

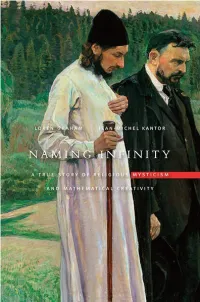

Naming Infinity: a True Story of Religious Mysticism And

Naming Infinity Naming Infinity A True Story of Religious Mysticism and Mathematical Creativity Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Graham, Loren R. Naming infinity : a true story of religious mysticism and mathematical creativity / Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-03293-4 (alk. paper) 1. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Religious aspects. 2. Mysticism—Russia (Federation) 3. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Philosophy. 4. Mathematics—France—Religious aspects. 5. Mathematics—France—Philosophy. 6. Set theory. I. Kantor, Jean-Michel. II. Title. QA27.R8G73 2009 510.947′0904—dc22â 2008041334 CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Storming a Monastery 7 2. A Crisis in Mathematics 19 3. The French Trio: Borel, Lebesgue, Baire 33 4. The Russian Trio: Egorov, Luzin, Florensky 66 5. Russian Mathematics and Mysticism 91 6. The Legendary Lusitania 101 7. Fates of the Russian Trio 125 8. Lusitania and After 162 9. The Human in Mathematics, Then and Now 188 Appendix: Luzin’s Personal Archives 205 Notes 212 Acknowledgments 228 Index 231 ILLUSTRATIONS Framed photos of Dmitri Egorov and Pavel Florensky. Photographed by Loren Graham in the basement of the Church of St. Tatiana the Martyr, 2004. 4 Monastery of St. Pantaleimon, Mt. Athos, Greece. 8 Larger and larger circles with segment approaching straight line, as suggested by Nicholas of Cusa. 25 Cantor ternary set. -

Universities and Empire

Universities and Empire MONEY AND POLITICS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES DURING THE COLD WAR Edited and Introduced by Christopher Simpson THE NEW PRESS * NEW YORK 1998 (Slava Gerovitch) Writing History in the Present Tense: Cold War-era Discursive Strategies of Soviet Historians of Science and Technology The study of Soviet discourse is a fascinating journey through multiple layers of meaning, exquisite rhetorical feats, and intentional paradoxes. Soviet leaders fairly early arrived at the idea of supplementing direct political censorship with more subtle ideological controls over disciplinary discourses. However, their attempts to supervise and homogenize public discourse simply did not reach its goals. The fragmented and unstable real ity of Soviet discourse was a far cry from the (purported) perfect orderliness of totalitarian discourse, so vividly imagined in George Orwell’s 1984 and in various Orwell-inspired studies.1 Only recently have scholars begun to explore the tensions, in consistencies, and uncertainties of Soviet discursive practices. Studies of political discourse provided a few illustrative examples of the complexities involved. Michael Gorham, for instance, has pointed to an essential conflict in Soviet political discourse: The more colloquial a tone Soviet propaganda assumed, the less it was capable of conveying abstract ideas and political symbols of the central state. When sophisticated political language was em ployed, it often caused frustration, distrust, and alienation on the part of peasants and workers.2 In another study, Rachel Walker 189 SLAVA GEROVITCH identified a “linguistic paradox” in Soviet political discourse, which stemmed from the necessity for Soviet leaders to maintain the appearance of continuity with the teachings of Marx and Le nin, and at the same time “creatively develop” Marxist-Leninist doctrine.3 An even more complex picture emerges when we turn from political texts to various disciplinary discourses characteristic of the Soviet academic community. -

The Phenomenon of Soviet Science

The Phenomenon of Soviet Science By Alexei Kojevnikov* ABSTRACT The grand “Soviet experiment” constituted an attempt to greatly accelerate and even shortcut the gradual course of historical development on the assumption of presumed knowledge of the general laws of history. This paper discusses the parts of that experiment that directly concerned scientifi c research and, in fact, anticipated or helped defi ne important global changes in the functioning of science as a profes- sion and an institution during the twentieth century. The phenomenon of Soviet, or socialist, science is analyzed here from the comparative international perspective, with attention to similarities and reciprocal infl uences, rather than to the contrasts and dichotomies that have traditionally interested cold war–type historiography. The problem is considered at several levels: philosophical (Soviet thought on the relationship between science and society and the social construction of scientifi c knowledge); institutional (the state recognition of research as a separate profession, the rise of big science and scientifi c research institutes); demographic (science be- coming a mass profession, with ethnic and gender diversity among scientists); and political (Soviet- inspired infl uences on the practice of science in Europe and the United States through the social relations of science movement of the 1930s and the Sputnik shock of the 1950s). SCIENCE AND SOVIET VALUES The fact that the Soviet Communist regime placed extraordinarily high value and ex- pectations upon science is, of course, rather well known. So much so, perhaps, that it has usually not been seen as a historical problem but has been taken for granted as something natural that does not ask for further discussion or inquiry. -

JD Bernal and the Replication of The

Clipboard J D Bernal and the replication of the genetic material – hindsight on foresight The 1931 International Congress for the History of Science held in London is famous for the sudden appearance of a powerful group from the USSR, led by Nikolai Bukharin (1888–1938). Their papers were rapidly published as a book (later reprinted) because there was almost no place for them in the time-table. These papers stimulated much interest in the social function of science and in the current philosophical outlook of the new communist state, especially as it was a time of great world economic and social unrest. However, the main business of the congress was elsewhere, and the Soviet intervention was nominally a sideshow, although it excited the main publicity. It enabled J D Bernal to meet Nikolai Bukharin and Boris Hessen with important consequences for attitudes to the role of science in society1. The papers read at the congress were not systematically published. J B S Haldane, already in 1923, in a lecture, “Daedalus or Science and the Future”, given in Cambridge to “The Heretics”2, had declared boldly that biology had become the centre of scientific interest. Biology was to be divested of mystical, religious and vitalistic principles and was henceforth to be investigated by materialist scientific methods. For Bernal, as Marx and Engels, not the most romantic people, wrote about Francis Bacon: “Matter smiled at man with poetic sensuous brightness”. The study of the arrangements of atoms was going to reveal the secrets of life, the universe and all that. Science had the power to liberate mankind from poverty, ignorance and hunger if only it could be applied properly. -

Science and Nation After Socialism in the Novosibirsk Scientific Center, Russia

Local Science, Global Knowledge: Science and Nation after Socialism in the Novosibirsk Scientific Center, Russia Amy Lynn Ninetto Mohnton, Pennsylvania B.A., Franklin and Marshall College, 1993 M.A., University of Virginia, 1997 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dcpartmcn1 of Anthropology University of Virginia May 2002 11 © Copyright by Amy Lynn Ninetta All Rights Reserved May 2002 lll Abstract This dissertation explores the changing relationships between science, the state, and global capital in the Novosibirsk Scientific Center (Akademgorodok). Since the collapse of the state-sponsored Soviet "big science" establishment, Russian scientists have been engaging transnational flows of capital, knowledge, and people. While some have permanently emigrated from Russia, others travel abroad on temporary contracts; still others work for foreign firms in their home laboratories. As they participate in these transnational movements, Akademgorodok scientists confront a number of apparent contradictions. On one hand, their transnational movement is, in many respects, seen as a return to the "natural" state of science-a reintegration of former Soviet scientists into a "world science" characterized by open exchange of information and transcendence of local cultural models of reality. On the other hand, scientists' border-crossing has made them-and the state that claims them as its national resources-increasingly conscious of the borders that divide world science into national and local scientific communities with differential access to resources, prestige, and knowledge. While scientists assert a specifically Russian way of doing science, grounded in the historical relationships between Russian science and the state, they are reaching sometimes uneasy accommodations with the globalization of scientific knowledge production.