Arxiv:1710.05659V1 [Math.HO]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics David Aubin, Catherine Goldstein

Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics David Aubin, Catherine Goldstein To cite this version: David Aubin, Catherine Goldstein. Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics. 2013. hal- 00830121v1 HAL Id: hal-00830121 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-00830121v1 Preprint submitted on 4 Jun 2013 (v1), last revised 8 Jul 2014 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics David Aubin and Catherine Goldstein Abstract. In the historical literature, opposite conclusions were drawn about the impact of the First World War on mathematics. In this chapter, the case is made that the war was an important event for the history of mathematics. We show that although mathematicians' experience of the war was extremely varied, its impact was decisive on the life of a great number of them. We present an overview of some uses of mathematics in war and of the development of mathematics during the war. We conclude by arguing that the war also was a crucial factor in the institutional modernization of mathematics. Les vrais adversaires, dans la guerre d'aujourd'hui, ce sont les professeurs de math´ematiques`aleur table, les physiciens et les chimistes dans leur laboratoire. -

Theological Metaphors in Mathematics

STUDIES IN LOGIC, GRAMMAR AND RHETORIC 44 (57) 2016 DOI: 10.1515/slgr-2016-0002 Stanisław Krajewski University of Warsaw THEOLOGICAL METAPHORS IN MATHEMATICS Abstract. Examples of possible theological influences upon the development of mathematics are indicated. The best known connection can be found in the realm of infinite sets treated by us as known or graspable, which constitutes a divine-like approach. Also the move to treat infinite processes as if they were one finished object that can be identified with its limits is routine in mathemati- cians, but refers to seemingly super-human power. For centuries this was seen as wrong and even today some philosophers, for example Brian Rotman, talk critically about “theological mathematics”. Theological metaphors, like “God’s view”, are used even by contemporary mathematicians. While rarely appearing in official texts they are rather easily invoked in “the kitchen of mathemat- ics”. There exist theories developing without the assumption of actual infinity the tools of classical mathematics needed for applications (For instance, My- cielski’s approach). Conclusion: mathematics could have developed in another way. Finally, several specific examples of historical situations are mentioned where, according to some authors, direct theological input into mathematics appeared: the possibility of the ritual genesis of arithmetic and geometry, the importance of the Indian religious background for the emergence of zero, the genesis of the theories of Cantor and Brouwer, the role of Name-worshipping for the research of the Moscow school of topology. Neither these examples nor the previous illustrations of theological metaphors provide a certain proof that religion or theology was directly influencing the development of mathematical ideas. -

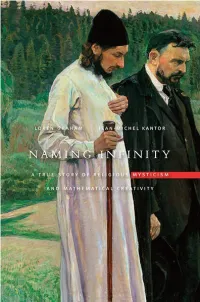

Naming Infinity: a True Story of Religious Mysticism And

Naming Infinity Naming Infinity A True Story of Religious Mysticism and Mathematical Creativity Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Graham, Loren R. Naming infinity : a true story of religious mysticism and mathematical creativity / Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-03293-4 (alk. paper) 1. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Religious aspects. 2. Mysticism—Russia (Federation) 3. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Philosophy. 4. Mathematics—France—Religious aspects. 5. Mathematics—France—Philosophy. 6. Set theory. I. Kantor, Jean-Michel. II. Title. QA27.R8G73 2009 510.947′0904—dc22â 2008041334 CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Storming a Monastery 7 2. A Crisis in Mathematics 19 3. The French Trio: Borel, Lebesgue, Baire 33 4. The Russian Trio: Egorov, Luzin, Florensky 66 5. Russian Mathematics and Mysticism 91 6. The Legendary Lusitania 101 7. Fates of the Russian Trio 125 8. Lusitania and After 162 9. The Human in Mathematics, Then and Now 188 Appendix: Luzin’s Personal Archives 205 Notes 212 Acknowledgments 228 Index 231 ILLUSTRATIONS Framed photos of Dmitri Egorov and Pavel Florensky. Photographed by Loren Graham in the basement of the Church of St. Tatiana the Martyr, 2004. 4 Monastery of St. Pantaleimon, Mt. Athos, Greece. 8 Larger and larger circles with segment approaching straight line, as suggested by Nicholas of Cusa. 25 Cantor ternary set. -

Science and Nation After Socialism in the Novosibirsk Scientific Center, Russia

Local Science, Global Knowledge: Science and Nation after Socialism in the Novosibirsk Scientific Center, Russia Amy Lynn Ninetto Mohnton, Pennsylvania B.A., Franklin and Marshall College, 1993 M.A., University of Virginia, 1997 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dcpartmcn1 of Anthropology University of Virginia May 2002 11 © Copyright by Amy Lynn Ninetta All Rights Reserved May 2002 lll Abstract This dissertation explores the changing relationships between science, the state, and global capital in the Novosibirsk Scientific Center (Akademgorodok). Since the collapse of the state-sponsored Soviet "big science" establishment, Russian scientists have been engaging transnational flows of capital, knowledge, and people. While some have permanently emigrated from Russia, others travel abroad on temporary contracts; still others work for foreign firms in their home laboratories. As they participate in these transnational movements, Akademgorodok scientists confront a number of apparent contradictions. On one hand, their transnational movement is, in many respects, seen as a return to the "natural" state of science-a reintegration of former Soviet scientists into a "world science" characterized by open exchange of information and transcendence of local cultural models of reality. On the other hand, scientists' border-crossing has made them-and the state that claims them as its national resources-increasingly conscious of the borders that divide world science into national and local scientific communities with differential access to resources, prestige, and knowledge. While scientists assert a specifically Russian way of doing science, grounded in the historical relationships between Russian science and the state, they are reaching sometimes uneasy accommodations with the globalization of scientific knowledge production. -

Mathematical Symbolism in a Russian Literary Masterpiece

MATHEMATICAL SYMBOLISM IN A RUSSIAN LITERARY MASTERPIECE NOAH GIANSIRACUSA∗ AND ANASTASIA VASILYEVA∗∗ ABSTRACT. Andrei Bely’s modernist novel Petersburg, first published in 1913, is considered a pinnacle of the Symbolist movement. Nabokov famously ranked it as one of the four greatest mas- terpieces of 20th-century prose. The author’s father, Bugaev, was an influential mathematician and for 12 years served as the president of the Moscow Mathematical Society; he was also a source of inspiration for one of the main characters in the son’s novel. While the philosophical views and po- litical leanings of the mathematicians surrounding Bely, and their impact on Petersburg, have been a topic of recent academic interest, there has not yet been a direct investigation of the surprisingly fre- quent and sophisticated mathematical passages in the book itself. We attempt here to rectify this gap in the scholarly literature, and in doing so find a rich tapestry of mathematical ideas and allusions. 1. INTRODUCTION Andrei Bely (1880-1934) was a fascinating, if somewhat tragic, figure. He grew up under the stern tutelage of his internationally renowned math professor father, Nikolai Bugaev (1837-1903), and studied the natural sciences at the University of Moscow before turning to the literary arts. In fact, it was because of the father’s fame and reputation that Bely took up a pseudonym when launching his literary career, rather than publishing under his birth name, Boris Bugaev [Moc77, p. 31]. Both father and son were polymaths with vast philosophical interests. They seemed intent on expanding the theoretical foundations of their respective subjects (math for the father, poetry and prose for the son) to quixotic extents: they believed they could explain, and even justify, historical events and contemporary social movements through their abstract work. -

Multiplication, Oil Spill, Arcimboldo – and Sliced Bread

Welcome to the 25th issue of the Primary Magazine. Our famous mathematician is Sierpiński, we look at the art of Giuseppe Arcimboldo, and our CPD opportunity aims to develop subject knowledge in multiplication. It’s in the News! features the oil spill disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. Contents Editor’s extras In this issue we tell you of some research about parents and the way they ‘help’ their children with mathematics. We also have news from one of our regional projects and a variety of things for you to look at. It’s in the News! We explore yet another disaster! This one is the oil leak caused by the explosion of the rig Deepwater Horizon in the Gulf of Mexico. The slides provide opportunities for work with such mathematical concepts as measurement, data handling, compass points and coordinates. The Art of Mathematics The art of Giuseppe Arcimboldo, born in Milan, Italy, in 1527. He is best known for his portraits of human heads made up of vegetables, fruits, sea creatures, tree roots and other everyday objects. Focus on… This article has to be ‘the greatest thing since sliced bread’! This month is the 82nd anniversary of the first sliced loaf of bread. The original loaf-slicing machine was invented by Otto Frederick Rohwedder. A little bit of history In this issue we look at a potted history of Sierpiński, a Polish mathematician well known for his contribution to various elements of mathematics, not least fractals. As well as finding out about the mathematician himself we explore his work on fractals, with ideas for great activities to do with your pupils. -

Visiting Mathematicians Jon Barwise, in Setting the Tone for His New Column, Has Incorporated Three Articles Into This Month's Offering

OTICES OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY The Growth of the American Mathematical Society page 781 Everett Pitcher ~~ Centennial Celebration (August 8-12) page 831 JULY/AUGUST 1988, VOLUME 35, NUMBER 6 Providence, Rhode Island, USA ISSN 0002-9920 Calendar of AMS Meetings and Conferences This calendar lists all meetings which have been approved prior to Mathematical Society in the issue corresponding to that of the Notices the date this issue of Notices was sent to the press. The summer which contains the program of the meeting. Abstracts should be sub and annual meetings are joint meetings of the Mathematical Associ mitted on special forms which are available in many departments of ation of America and the American Mathematical Society. The meet mathematics and from the headquarters office of the Society. Ab ing dates which fall rather far in the future are subject to change; this stracts of papers to be presented at the meeting must be received is particularly true of meetings to which no numbers have been as at the headquarters of the Society in Providence, Rhode Island, on signed. Programs of the meetings will appear in the issues indicated or before the deadline given below for the meeting. Note that the below. First and supplementary announcements of the meetings will deadline for abstracts for consideration for presentation at special have appeared in earlier issues. sessions is usually three weeks earlier than that specified below. For Abstracts of papers presented at a meeting of the Society are pub additional information, consult the meeting announcements and the lished in the journal Abstracts of papers presented to the American list of organizers of special sessions. -

A Note About Mikhaïl Lavrentieff and His World of Analysis in the Soviet Union (With an Appendix by Galina Sinkevich) Athanase Papadopoulos

A note about Mikhaïl Lavrentieff and his world of analysis in the Soviet Union (With an appendix by Galina Sinkevich) Athanase Papadopoulos To cite this version: Athanase Papadopoulos. A note about Mikhaïl Lavrentieff and his world of analysis in the Soviet Union (With an appendix by Galina Sinkevich). 2019. hal-02406071 HAL Id: hal-02406071 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02406071 Preprint submitted on 12 Dec 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A NOTE ABOUT MIKHA¨IL LAVRENTIEFF AND HIS WORLD OF ANALYSIS IN THE SOVIET UNION ATHANASE PAPADOPOULOS WITH AN APPENDIX BY GALINA SINKEVICH Abstract. We survey the life and work of Mikha¨ıl Lavrentieff, one of the main founders of the theory of quasiconformal mappings, with an emphasis on his training years at the famous Moscow school of theory of functions founded by Luzin. We also mention the major applications of quasiconformal mappings that Lavrentieff developed in the physical sciences. At the same time, we re- view several connected historical events, including the sad fate of Luzin during the Stalin period, the birth of the scientific Siberian center of Akademgorodok, and the role that Lavrentieff played in the organization of science and research in the Soviet Union. -

Pursuing the Infinite the Mathematicians and the Heretical Sect Is Not in Doubt

NATURE|Vol 458|23 April 2009 OPINION population are sustained for the rest of this the best we can hope is that we can manage that some infinite sets were larger than others. century, but at a huge cost — the complete them ourselves, taking over the heavy respon- A group of French mathematicians at the turn loss of all the natural ecosystems of the world. sibility for keeping Earth habitable, which Gaia of the century — including Emile Borel, Henri Most of us, living in cities and insulated from once did for us automatically. Lebesgue and René Baire — were searching the natural environment, would barely notice The more likely outcome is that we would for a systematic way to determine the size of until it was too late to do anything about it. barely manage them at all. In that case, we these infinite sets. This aroused the scepticism This is what many politicians, economists and would face a sequence of global environmental of colleagues such as Henri Poincaré, who industrialists seem to want — their mantra of crises and a steady degradation of the planetary claimed that Cantor’s hierarchy of infinities unceasing economic growth implies that we environment that would eventually kill just as had “a whiff of form without matter, which should take for ourselves all Gaia’s resources many of us as a sudden collapse. Given that, is repugnant to the French spirit”. According and squeeze from them the maximum short- perhaps we had better hope that Lovelock is to the authors, the French researchers found term gain, leaving nothing for the future. -

1 Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor a Comparison of Two Cultural Approaches to Mathematics: France and Russia, 1890-19301 “

1 Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor A Comparison of Two Cultural Approaches to Mathematics: France and Russia, 1890-19301 “. das Wesen der Mathematik liegt gerade in ihrer Freiheit” Georg Cantor, 18832 Many people would like to know where new scientific ideas come from, and how they arise. This subject is of interest to scientists of course, historians and philosophers of science, psychologists, and many others. In the case of mathematics, new ideas often come in the form of new “mathematical objects:” groups, vector spaces, sets, etc. Some people think these new objects are invented in the brains of mathematicians; others believe they are in some sense discovered, perhaps in a platonistic world. We think it would be interesting to study how these questions have been confronted by two different groups of mathematicians working on the same problems at the same time, but in two contrasting cultural environments. Will the particular environment influence the way mathematicians in each of the two groups see their work, and perhaps even help them reach conclusions different from those of the other group? We are exploring this issue 2 in the period 1890-1930 in France and Russia on the subject of the birth of the descriptive theory of sets. In the Russian case we have found that a particular theological view – that of the “Name Worshippers” – played a role in the discussions of the nature of mathematics. The Russian mathematicians influenced by this theological viewpoint believed that they had greater freedom to create mathematical objects than did their French colleagues subscribing to rationalistic and secular principles. -

Polish Mathematicians and Mathematics in World War I. Part II

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Portal Czasopism Naukowych (E-Journals) Science in Poland Stanisław Domoradzki ORCID 0000-0002-6511-0812 University of Rzeszów (Rzeszów, Poland) [email protected] Małgorzata Stawiska ORCID 0000-0001-5704-7270 American Mathematical Society (Ann Arbor, USA) [email protected] Polish mathematicians and mathematics in World War I. Part II. Russian Empire Abstract In the second part of our article we continue presentation of individual fates of Polish mathematicians (in a broad sense) and the formation of modern Polish mathematical community against the background of the events of World War I. In particu- lar we focus on the situations of Polish mathematicians in the Russian Empire (including those affiliated with the University of Warsaw, reactivated by Germans, and the Warsaw Polytechnic, founded already by Russians) and other countries. PUBLICATION e-ISSN 2543-702X INFO ISSN 2451-3202 DIAMOND OPEN ACCESS CITATION Domoradzki, Stanisław; Stawiska, Małgorzata 2019: Polish mathematicians and mathematics in World War I. Part II: Russian Empire. Studia Historiae Scientiarum 18, pp. 55–92. DOI: 10.4467/2543702XSHS.19.004.11010. ARCHIVE RECEIVED: 13.11.2018 LICENSE POLICY ACCEPTED: 16.05.2019 Green SHERPA / PUBLISHED ONLINE: 15.11.2019 RoMEO Colour WWW http://www.ejournals.eu/sj/index.php/SHS/; http://pau.krakow.pl/Studia-Historiae-Scientiarum/ Stanisław Domoradzki, Małgorzata Stawiska Polish mathematicians and mathematics ... Keywords: Polish mathematical community, World War I, Russian Empire, Society for Scientific Courses in Warsaw, Polish University College in Kiev, teaching at the academic level outside traditional institutions, Mathematics Subject Classification: 01A60, 01A70, 01A73, 01A74 Polscy matematycy i polska matematyka w czasach I wojny światowej. -

Polish Mathematicians and Mathematics in World War I. Part II

Science in Poland Stanisław Domoradzki ORCID 0000-0002-6511-0812 University of Rzeszów (Rzeszów, Poland) [email protected] Małgorzata Stawiska ORCID 0000-0001-5704-7270 American Mathematical Society (Ann Arbor, USA) [email protected] Polish mathematicians and mathematics in World War I. Part II. Russian Empire Abstract In the second part of our article we continue presentation of individual fates of Polish mathematicians (in a broad sense) and the formation of modern Polish mathematical community against the background of the events of World War I. In particu- lar we focus on the situations of Polish mathematicians in the Russian Empire (including those affiliated with the University of Warsaw, reactivated by Germans, and the Warsaw Polytechnic, founded already by Russians) and other countries. PUBLICATION e-ISSN 2543-702X INFO ISSN 2451-3202 DIAMOND OPEN ACCESS CITATION Domoradzki, Stanisław; Stawiska, Małgorzata 2019: Polish mathematicians and mathematics in World War I. Part II: Russian Empire. Studia Historiae Scientiarum 18, pp. 55–92. DOI: 10.4467/2543702XSHS.19.004.11010. ARCHIVE RECEIVED: 13.11.2018 LICENSE POLICY ACCEPTED: 16.05.2019 Green SHERPA / PUBLISHED ONLINE: 15.11.2019 RoMEO Colour WWW http://www.ejournals.eu/sj/index.php/SHS/; http://pau.krakow.pl/Studia-Historiae-Scientiarum/ Stanisław Domoradzki, Małgorzata Stawiska Polish mathematicians and mathematics ... Keywords: Polish mathematical community, World War I, Russian Empire, Society for Scientific Courses in Warsaw, Polish University College in Kiev, teaching at the academic level outside traditional institutions, Mathematics Subject Classification: 01A60, 01A70, 01A73, 01A74 Polscy matematycy i polska matematyka w czasach I wojny światowej. Część II. Cesarstwo Rosyjskie Abstrakt W drugiej części artykułu kontynuujemy przedstawianie indy- widualnych losów matematyków polskich (w szerokim sensie) oraz kształtowanie się nowoczesnego polskiego środowiska matematycznego na tle wydarzeń I wojny światowej.