Programming the USSR: Leonid V. Kantorovich in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ties That Bind Olga Alexandrovna Ladyzhenskaya and the 2022 ICM in St. Petersburg

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Math and Computer Science Faculty Publications Math and Computer Science 3-2020 The Ties That Bind Olga Alexandrovna Ladyzhenskaya and the 2022 ICM in St. Petersburg Della Dumbaugh University of Richmond, [email protected] Panagiota Daskalopoulos Anatoly Vershik Lev Kapitanski Nicolai Reshetikhin See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/mathcs-faculty-publications Recommended Citation Dumbaugh, Della, Panagiota Daskalopoulos, Anatoly Vershik, Lev Kapitanski, Nicolai Reshetikhin, Darya Apushkinskaya, and Alexander Nazarov. “The Ties That Bind: Olga Alexandrovna Ladyzhenskaya and the 2022 ICM in St. Petersburg.” Notices of the American Mathematical Society 67 (March 2020): 373–81. https://doi.org/10.1090/noti2047. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Math and Computer Science at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Math and Computer Science Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Della Dumbaugh, Panagiota Daskalopoulos, Anatoly Vershik, Lev Kapitanski, Nicolai Reshetikhin, Darya Apushkinskaya, and Alexander Nazarov This article is available at UR Scholarship Repository: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/mathcs-faculty-publications/ 237 HISTORY The Ties That Bind Olga Alexandrovna Ladyzhenskaya and the 2022 ICM in St. Petersburg Della Dumbaugh, Panagiota -

Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics David Aubin, Catherine Goldstein

Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics David Aubin, Catherine Goldstein To cite this version: David Aubin, Catherine Goldstein. Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics. 2013. hal- 00830121v1 HAL Id: hal-00830121 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-00830121v1 Preprint submitted on 4 Jun 2013 (v1), last revised 8 Jul 2014 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Placing World War I in the History of Mathematics David Aubin and Catherine Goldstein Abstract. In the historical literature, opposite conclusions were drawn about the impact of the First World War on mathematics. In this chapter, the case is made that the war was an important event for the history of mathematics. We show that although mathematicians' experience of the war was extremely varied, its impact was decisive on the life of a great number of them. We present an overview of some uses of mathematics in war and of the development of mathematics during the war. We conclude by arguing that the war also was a crucial factor in the institutional modernization of mathematics. Les vrais adversaires, dans la guerre d'aujourd'hui, ce sont les professeurs de math´ematiques`aleur table, les physiciens et les chimistes dans leur laboratoire. -

Theological Metaphors in Mathematics

STUDIES IN LOGIC, GRAMMAR AND RHETORIC 44 (57) 2016 DOI: 10.1515/slgr-2016-0002 Stanisław Krajewski University of Warsaw THEOLOGICAL METAPHORS IN MATHEMATICS Abstract. Examples of possible theological influences upon the development of mathematics are indicated. The best known connection can be found in the realm of infinite sets treated by us as known or graspable, which constitutes a divine-like approach. Also the move to treat infinite processes as if they were one finished object that can be identified with its limits is routine in mathemati- cians, but refers to seemingly super-human power. For centuries this was seen as wrong and even today some philosophers, for example Brian Rotman, talk critically about “theological mathematics”. Theological metaphors, like “God’s view”, are used even by contemporary mathematicians. While rarely appearing in official texts they are rather easily invoked in “the kitchen of mathemat- ics”. There exist theories developing without the assumption of actual infinity the tools of classical mathematics needed for applications (For instance, My- cielski’s approach). Conclusion: mathematics could have developed in another way. Finally, several specific examples of historical situations are mentioned where, according to some authors, direct theological input into mathematics appeared: the possibility of the ritual genesis of arithmetic and geometry, the importance of the Indian religious background for the emergence of zero, the genesis of the theories of Cantor and Brouwer, the role of Name-worshipping for the research of the Moscow school of topology. Neither these examples nor the previous illustrations of theological metaphors provide a certain proof that religion or theology was directly influencing the development of mathematical ideas. -

Boenig-Liptsin / Entrepreneurs of the Mind / 1 Citizen's Mind

Margo Boenig-Liptsin SIGCIS Workshop, November 9, 2014 Work in !rogress Session "orking draft – please do not cite (ear SIGCIS Workshop !articipants) *hank you $or reading this partial draft of one of my dissertation 'hapters) I-m submitting to your review a draft of a 'hapter $rom the mi##&e of my dissertation, therefore to contextualize the "riting that you "i&& be reading, I inc&ude be&ow an abstract of my "hole dissertation project and a chapter out&ine. 2s you "i&& see, this early draft of Chapter 2 is based primari&y on empirical research of my three national cases1 I haven't yet integrated into it any secondary &iterature. I "ould be very gratef,& $or your suggestions of re$erences that you $eel "ould be interesting $or me to incorporate/refect upon, especial&y $rom the &iterature on the history of computing, given the topi's that I am exploring in this chapter or in the dissertation as a "hole. *his early draft is also missing complete $ootnotes—they are current&y 0ust notes $or mysel$ and references that I need to tidy up. I-m gratef,& $or al& of your comments, "hich "i&& no doubt make the next #raft of this signifcant&y better) Best "ishes, Margo (issertation abstract Making the Citi/en of the Information 2ge7 2 comparative study of computer &iteracy programs $or 'hi&dren, 1960s-1990s My dissertation is a comparative history of the frst computer &iteracy programs $or chi&dren. *he project examines how programs to introduce 'hi&dren to computers in the 9nited States, :rance, and the Soviet 9nion $rom the 1960s to 1990s embodied political, epistemic, and moral debates about the kind of citi/en required $or &i$e in the 21st century. -

Nikolay Luzin, His Students, Adversaries, and Defenders (Notes

Nikolay Luzin, his students, adversaries, and defenders (notes on the history of Moscow mathematics, 1914-1936) Yury Neretin This is historical-mathematical and historical notes on Moscow mathematics 1914-1936. Nikolay Luzin was a central figure of that time. Pavel Alexandroff, Nina Bari, Alexandr Khinchin, Andrey Kolmogorov, Mikhail Lavrentiev, Lazar Lyusternik, Dmitry Menshov, Petr Novikov, Lev Sсhnirelman, Mikhail Suslin, and Pavel Urysohn were his students. We discuss the time of the great intellectual influence of Luzin (1915-1924), the time of decay of his school (1922-1930), a moment of his administrative power (1934-1936), and his fall in July 1936. But the thing which served as a source of Luzin’s inner drama turned out to be a source of his subsequent fame... Lazar Lyusternik [351] Il est temps que je m’arr ete: voici que je dis, ce que j’ai d´eclar´e, et avec raison, ˆetre inutile `adire. Henri Lebesgue, Preface to Luzin’s book, Leˇcons sur les ensembles analytiques et leurs applications, [288] Прошло сто лет и что ж осталось От сильных, гордых сих мужей, Столь полных волею страстей? Их поколенье миновалось Alexandr Pushkin ’Poltava’ There is a common idea that a life of Nikolay Luzin can be a topic of a Shakespeare drama. I am agree with this sentence but I am extremely far from an intention to realize this idea. The present text is an impassive historical-mathematical and historical investigation of Moscow mathematics of that time. On the other hand, this is more a story of its initiation and turning moments than a history of achievements. -

Bfm:978-1-4612-2582-9/1.Pdf

Progress in Mathematics Volume 131 Series Editors Hyman Bass Joseph Oesterle Alan Weinstein Functional Analysis on the Eve of the 21st Century Volume I In Honor of the Eightieth Birthday of I. M. Gelfand Simon Gindikin James Lepowsky Robert L. Wilson Editors Birkhauser Boston • Basel • Berlin Simon Gindikin James Lepowsky Department of Mathematics Department of Mathematics Rutgers University Rutgers University New Brunswick, NJ 08903 New Brunswick, NJ 08903 Robert L. Wilson Department of Mathematics Rutgers University New Brunswick, NJ 08903 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Functional analysis on the eve of the 21 st century in honor of the 80th birthday 0fI. M. Gelfand I [edited) by S. Gindikin, 1. Lepowsky, R. Wilson. p. cm. -- (Progress in mathematics ; vol. 131) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13:978-1-4612-7590-9 e-ISBN-13:978-1-4612-2582-9 DOl: 10.1007/978-1-4612-2582-9 1. Functional analysis. I. Gel'fand, I. M. (lzraU' Moiseevich) II. Gindikin, S. G. (Semen Grigor'evich) III. Lepowsky, J. (James) IV. Wilson, R. (Robert), 1946- . V. Series: Progress in mathematics (Boston, Mass.) ; vol. 131. QA321.F856 1995 95-20760 515'.7--dc20 CIP Printed on acid-free paper d»® Birkhiiuser ltGD © 1995 Birkhliuser Boston Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1995 Copyright is not claimed for works of u.s. Government employees. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright owner. -

Bart, Hempfling, Kaashoek. (Eds.) Israel Gohberg and Friends.. on The

Israel Gohberg and Friends On the Occasion of his 80th Birthday Harm Bart Thomas Hempfling Marinus A. Kaashoek Editors Birkhäuser Basel · Boston · Berlin Editors: Harm Bart Marinus A. Kaashoek Econometrisch Instituut Department of Mathematics, FEW Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam Vrije Universiteit Postbus 1738 De Boelelaan 1081A 3000 DR Rotterdam 1081 HV Amsterdam The Netherlands The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Thomas Hempfling Editorial Department Mathematics Birkhäuser Publishing Ltd. P.O. Box 133 4010 Basel Switzerland e-mail: thomas.hempfl[email protected] Library of Congress Control Number: 2008927170 Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at <http://dnb.ddb.de>. ISBN 978-3-7643-8733-4 Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel – Boston – Berlin This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, re-use of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in other ways, and storage in data banks. For any kind of use permission of the copyright owner must be obtained. © 2008 Birkhäuser Verlag AG Basel · Boston · Berlin P.O. Box 133, CH-4010 Basel, Switzerland Part of Springer Science+Business Media Printed on acid-free paper produced of chlorine-free pulp. TCF ∞ Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-7643-8733-4 e-ISBN 978-3-7643-8734-1 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 www.birkhauser.ch Contents Preface.......................................................................ix CongratulationsfromthePublisher...........................................xii PartI.MathematicalandPhilosophical-MathematicalTales...................1 I. -

“To Be a Good Mathematician, You Need Inner Voice” ”Огонёкъ” Met with Yakov Sinai, One of the World’S Most Renowned Mathematicians

“To be a good mathematician, you need inner voice” ”ОгонёкЪ” met with Yakov Sinai, one of the world’s most renowned mathematicians. As the new year begins, Russia intensifies the preparations for the International Congress of Mathematicians (ICM 2022), the main mathematical event of the near future. 1966 was the last time we welcomed the crème de la crème of mathematics in Moscow. “Огонёк” met with Yakov Sinai, one of the world’s top mathematicians who spoke at ICM more than once, and found out what he thinks about order and chaos in the modern world.1 Committed to science. Yakov Sinai's close-up. One of the most eminent mathematicians of our time, Yakov Sinai has spent most of his life studying order and chaos, a research endeavor at the junction of probability theory, dynamical systems theory, and mathematical physics. Born into a family of Moscow scientists on September 21, 1935, Yakov Sinai graduated from the department of Mechanics and Mathematics (‘Mekhmat’) of Moscow State University in 1957. Andrey Kolmogorov’s most famous student, Sinai contributed to a wealth of mathematical discoveries that bear his and his teacher’s names, such as Kolmogorov-Sinai entropy, Sinai’s billiards, Sinai’s random walk, and more. From 1998 to 2002, he chaired the Fields Committee which awards one of the world’s most prestigious medals every four years. Yakov Sinai is a winner of nearly all coveted mathematical distinctions: the Abel Prize (an equivalent of the Nobel Prize for mathematicians), the Kolmogorov Medal, the Moscow Mathematical Society Award, the Boltzmann Medal, the Dirac Medal, the Dannie Heineman Prize, the Wolf Prize, the Jürgen Moser Prize, the Henri Poincaré Prize, and more. -

Excerpts from Kolmogorov's Diary

Asia Pacific Mathematics Newsletter Excerpts from Kolmogorov’s Diary Translated by Fedor Duzhin Introduction At the age of 40, Andrey Nikolaevich Kolmogorov (1903–1987) began a diary. He wrote on the title page: “Dedicated to myself when I turn 80 with the wish of retaining enough sense by then, at least to be able to understand the notes of this 40-year-old self and to judge them sympathetically but strictly”. The notes from 1943–1945 were published in Russian in 2003 on the 100th anniversary of the birth of Kolmogorov as part of the opus Kolmogorov — a three-volume collection of articles about him. The following are translations of a few selected records from the Kolmogorov’s diary (Volume 3, pages 27, 28, 36, 95). Sunday, 1 August 1943. New Moon 6:30 am. It is a little misty and yet a sunny morning. Pusya1 and Oleg2 have gone swimming while I stay home being not very well (though my condition is improving). Anya3 has to work today, so she will not come. I’m feeling annoyed and ill at ease because of that (for the second time our Sunday “readings” will be conducted without Anya). Why begin this notebook now? There are two reasonable explanations: 1) I have long been attracted to the idea of a diary as a disciplining force. To write down what has been done and what changes are needed in one’s life and to control their implementation is by no means a new idea, but it’s equally relevant whether one is 16 or 40 years old. -

Shaw' Preemia

Shaw’ preemia 2002. a rajas Hongkongi ajakirjandusmagnaat ja tuntud filantroop sir Run Run Shaw (s 1907) omanimelise fondi, et anda v¨alja iga-aastast preemiat – Shaw’ preemiat. Preemiaga autasustatakse ”isikut, s˜oltumata rassist, rahvusest ja religioossest taustast, kes on saavutanud olulise l¨abimurde akadeemilises ja teaduslikus uuri- mist¨o¨os v˜oi rakendustes ning kelle t¨o¨o tulemuseks on positiivne ja sugav¨ m˜oju inimkonnale.” Preemiat antakse v¨alja kolmel alal – astronoomias, loodusteadustes ja meditsiinis ning matemaatikas. Preemia suurus 2009. a oli uks¨ miljon USA dollarit. Preemiaga kaas- neb ka medal (vt joonist). Esimesed preemiad omistati 2004. a. Ajakirjanikud on ristinud Shaw’ preemia Ida Nobeli preemiaks (the Nobel of the East). Shaw’ preemiaid aastail 2009–2011 matemaatika alal m¨a¨arab komisjon, kuhu kuuluvad: esimees: Sir Michael Atiyah (Edinburghi Ulikool,¨ UK) liikmed: David Kazhdan (Jeruusalemma Heebrea Ulikool,¨ Iisrael) Peter C. Sarnak (Princetoni Ulikool,¨ USA) Yum-Tong Siu (Harvardi Ulikool,¨ USA) Margaret H. Wright (New Yorgi Ulikool,¨ USA) 2009. a Shaw’ preemia matemaatika alal kuulutati v¨alja 16. juunil Hongkongis ja see anti v˜ordses osas kahele matemaatikule: 293 Eesti Matemaatika Selts Aastaraamat 2009 Autori~oigusEMS, 2010 294 Shaw’ preemia Simon K. Donaldsonile ja Clifford H. Taubesile s¨arava panuse eest kolme- ja neljam˜o˜otmeliste muutkondade geomeetria arengusse. Premeerimistseremoonia toimus 7. oktoobril 2009. Sellel osales ka sir Run Run Shaw. Siin pildil on sir Run Run Shaw 100-aastane. Simon K. Donaldson sundis¨ 1957. a Cambridge’is (UK) ja on Londonis Imperial College’i Puhta Matemaatika Instituudi direktor ja professor. Bakalaureusekraadi sai ta 1979. a Pembroke’i Kolled- ˇzistCambridge’s ja doktorikraadi 1983. -

Alwyn C. Scott

the frontiers collection the frontiers collection Series Editors: A.C. Elitzur M.P. Silverman J. Tuszynski R. Vaas H.D. Zeh The books in this collection are devoted to challenging and open problems at the forefront of modern science, including related philosophical debates. In contrast to typical research monographs, however, they strive to present their topics in a manner accessible also to scientifically literate non-specialists wishing to gain insight into the deeper implications and fascinating questions involved. Taken as a whole, the series reflects the need for a fundamental and interdisciplinary approach to modern science. Furthermore, it is intended to encourage active scientists in all areas to ponder over important and perhaps controversial issues beyond their own speciality. Extending from quantum physics and relativity to entropy, consciousness and complex systems – the Frontiers Collection will inspire readers to push back the frontiers of their own knowledge. Other Recent Titles The Thermodynamic Machinery of Life By M. Kurzynski The Emerging Physics of Consciousness Edited by J. A. Tuszynski Weak Links Stabilizers of Complex Systems from Proteins to Social Networks By P. Csermely Quantum Mechanics at the Crossroads New Perspectives from History, Philosophy and Physics Edited by J. Evans, A.S. Thorndike Particle Metaphysics A Critical Account of Subatomic Reality By B. Falkenburg The Physical Basis of the Direction of Time By H.D. Zeh Asymmetry: The Foundation of Information By S.J. Muller Mindful Universe Quantum Mechanics and the Participating Observer By H. Stapp Decoherence and the Quantum-to-Classical Transition By M. Schlosshauer For a complete list of titles in The Frontiers Collection, see back of book Alwyn C. -

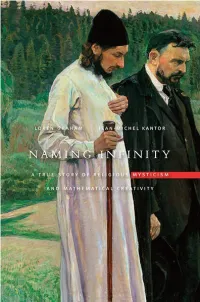

Naming Infinity: a True Story of Religious Mysticism And

Naming Infinity Naming Infinity A True Story of Religious Mysticism and Mathematical Creativity Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Graham, Loren R. Naming infinity : a true story of religious mysticism and mathematical creativity / Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-03293-4 (alk. paper) 1. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Religious aspects. 2. Mysticism—Russia (Federation) 3. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Philosophy. 4. Mathematics—France—Religious aspects. 5. Mathematics—France—Philosophy. 6. Set theory. I. Kantor, Jean-Michel. II. Title. QA27.R8G73 2009 510.947′0904—dc22â 2008041334 CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Storming a Monastery 7 2. A Crisis in Mathematics 19 3. The French Trio: Borel, Lebesgue, Baire 33 4. The Russian Trio: Egorov, Luzin, Florensky 66 5. Russian Mathematics and Mysticism 91 6. The Legendary Lusitania 101 7. Fates of the Russian Trio 125 8. Lusitania and After 162 9. The Human in Mathematics, Then and Now 188 Appendix: Luzin’s Personal Archives 205 Notes 212 Acknowledgments 228 Index 231 ILLUSTRATIONS Framed photos of Dmitri Egorov and Pavel Florensky. Photographed by Loren Graham in the basement of the Church of St. Tatiana the Martyr, 2004. 4 Monastery of St. Pantaleimon, Mt. Athos, Greece. 8 Larger and larger circles with segment approaching straight line, as suggested by Nicholas of Cusa. 25 Cantor ternary set.