Angle of Attack: Harrison Storms and the Race to the Moon by Mike Gray

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apollo Program 1 Apollo Program

Apollo program 1 Apollo program The Apollo program was the third human spaceflight program carried out by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the United States' civilian space agency. First conceived during the Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower as a three-man spacecraft to follow the one-man Project Mercury which put the first Americans in space, Apollo was later dedicated to President John F. Kennedy's national goal of "landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth" by the end of the 1960s, which he proposed in a May 25, 1961 address to Congress. Project Mercury was followed by the two-man Project Gemini (1962–66). The first manned flight of Apollo was in 1968 and it succeeded in landing the first humans on Earth's Moon from 1969 through 1972. Kennedy's goal was accomplished on the Apollo 11 mission when astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed their Lunar Module (LM) on the Moon on July 20, 1969 and walked on its surface while Michael Collins remained in lunar orbit in the command spacecraft, and all three landed safely on Earth on July 24. Five subsequent Apollo missions also landed astronauts on the Moon, the last in December 1972. In these six spaceflights, 12 men walked on the Moon. Apollo ran from 1961 to 1972, and was supported by the two-man Gemini program which ran concurrently with it from 1962 to 1966. Gemini missions developed some of the space travel techniques that were necessary for the success of the Apollo missions. -

Collection of Research Materials for the HBO Television Series, from the Earth to the Moon, 1940-1997, Bulk 1958-1997

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8290214d No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Research Materials for the HBO Television Series, From the Earth to the Moon, 1940-1997, bulk 1958-1997 Processed by Manuscripts Division staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé © 2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. 561 1 Finding Aid for the Collection of Research Materials for the HBO Television Series, From the Earth to the Moon, 1940-1997, bulk 1958-1997 Collection number: 561 UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Los Angeles, CA Processed by: Manuscripts Division staff, 2004 Encoded by: Caroline Cubé © 2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Collection of Research Materials for the HBO Television Series, From the Earth to the Moon, Date (inclusive): 1940-1997, bulk 1958-1997 Collection number: 561 Creator: Home Box Office (Firm) Extent: 86 boxes (43 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Dept. of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Abstract: From the earth to the moon was a Clavius Base/Imagine Entertainment production that followed the experiences of the Apollo astronauts in their mission to place a man on the moon. The collection covers a variety of subjects related to events and issues of the United States manned space flight program through Project Apollo and the history of the decades it covered, primarily the 1960s and the early 1970s. The collection contains books, magazines, unidentified excerpts from books and magazines, photographs, videorecordings, glass slides and audiotapes. -

Astronaut Candidacy and Selection

5/2/2019 Show Apache Solr Results in Table Published on dms_public.local.dev (https://historydms.hq.nasa.gov) Show Apache Solr Results in Table Displaying 1 - 17 of 17 Highlight On Summary View Show All Sort Result Set Record Number 30030 Series: ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEWS Document Type: ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEWS Publish_status: Public Approval Status: APPROVED FOR PUBLIC Subject: YOUNG, JOHN W. Location: ELECTRONIC DOCUMENT Folder Title: YOUNG, JOHN W. ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW Period Covered: 1974-06-28: JUNE 28, 1974 Description: Oral history interview with John W. Young conducted by Robert Sherrod for unpublished book on the Apollo program re current astronaut assignments, Young's education, Young's selection as part of second class of astronauts, Gus Grissom, training for Gemini 3 flight, Gemini 3 flight, Gemini 10 flight, how Young became command module (CM) pilot on Apollo 10 flight, Young's involvement with Apollo 13 flight, steering an Apollo CM through reentry, difference between space photography and the human eye, Apollo 16 astronaut training, Apollo 16 flight, what Young did in space between Apollo 1 (AS-204) fire and Apollo 7 flight, and when NASA would select Space Shuttle astronauts. Name(s) YOUNG, JOHN W. SHERROD, ROBERT GRISSOM, VIRGIL I. ("GUS") Topics: APOLLO PROGRAM, ASTRONAUT OFFICE, ASTRONAUT SELECTION, ASTRONAUT TRAINING, GEMINI 3 FLIGHT, GEMINI 10 FLIGHT, APOLLO 10 FLIGHT, APOLLO 13 FLIGHT, APOLLO 16 FLIGHT Access Type: GUEST Updated By: esuckow Last Update: 2019-04-03T17:39:00Z Record Number 31128 Series: ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEWS Document Type: ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEWS, TRANSCRIPTS Publish_status: Public Approval Status: APPROVED FOR PUBLIC Subject: DONLAN, CHARLES J. -

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)

Description of document: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Report on Episodes from American History Where the Federal Government Fostered Critical Activities for the Public Good 2014 Requested date: 26-October-2020 Release date: 13-November-2020 Posted date: 22-February-2021 Source of document: FOIA Request NASA Headquarters 300 E Street, SW Room 5Q16 Washington, DC 20546 Fax: (202) 358-4332 Email: [email protected] Online FOIA submission form The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. National Aeronautics and Space Administration Headquarters Washington, DC 20546-0001 November 13, 2020 Office of Communications Re: FOIA Tracking Number 21-NSSC-F-00054 This letter acknowledges receipt of your October 26, 2020 Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the NASA Headquarters FOIA Office. -

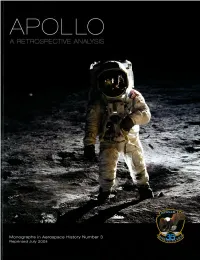

Apollo: a Retrospective Analysis

APOLLO --A RETROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS~-- by Roger D. Launius NASA History Office Code IQ Office of External Relations NASA Headquarters Washington, DC 20546 MONOGRAPHS IN AEROSPACE HISTORY NUMBER 3 NASA SP-2004-4503 Reprinted July 2004 APOLLO: A RETROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS PREFACE The program to land an American on the Moon and return safely to Earth in the 1960s has been called by some observers a defining event of the twentieth century. Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., even suggested that when Americans two centuries hence study the twentieth century, they will view the Apollo lunar landing as the critical event of the century. While that conclusion might be premature, there can be little doubt but that the flight of Apollo II in particular and the overall Apollo program in general was a high point in humanity's quest to explore the universe beyond Earth. Since the completion of Project Apollo more than twenty years ago there have been a plethora of books, stud ies, reports, and articles about its origin, execution, and meaning. At the time of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the first landing, it is appropriate to reflect on the effort and its place in U.S. and NASA history. This monograph has been written as a means to this end. It presents a short narrative account of Apollo from its origin through its assessment. That is followed by a mission by mission summary of the Apollo flights and concluded by a series of key documents relative to the program reproduced in facsimile. The intent of this monograph is to provide a basic history along with primary documents that may be useful to NASA personnel and others desiring informa tion about Apollo. -

From the Earth to the Moon Episode Guide Episodes 001–012

From the Earth to the Moon Episode Guide Episodes 001–012 Last episode aired Saturday May 10, 1998 www.hbo.com c c 1998 www.tv.com c 1998 www.hbo.com c 1998 c 1998 www.dvdtalk.com garethon.blogspot.it The summaries and recaps of all the From the Earth to the Moon episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http://www.hbo.com and http://garethon.blogspot.it and http://www.dvdtalk.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ! This booklet was LATEXed on November 6, 2018 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.61 Contents Season 1 1 1 Can We Do This? . .3 2 Apollo 1 . .5 3 We Have Cleared The Tower . .7 4 1968...............................................9 5 Spider . 11 6 Mare Tranquilitatis . 13 7 That’s All There Is . 15 8 We Interrupt This Program . 17 9 For Miles And Miles . 19 10 Galileo Was Right . 21 11 The Original Wives’ Club . 23 12 Le Voyage Dans La Lune . 25 Actor Appearances 27 From the Earth to the Moon Episode Guide II Season One From the Earth to the Moon Episode Guide Can We Do This? Season 1 Episode Number: 1 Season Episode: 1 Originally aired: Saturday April 5, 1998 Writer: Steven Katz Director: Tom Hanks Show Stars: Chris Isaak (Astronaut Edward White II), Timothy Daly (Astronaut James Lovell), Bryan Cranston (Astronaut Edwin ”Buzz” Aldrin), Peter Scolari (Astronaut Pete Conrad), Mark Rolston (Astronaut Gus Gris- som), Ben Marley (Astronaut Roger Chaffee), Steve Hofvendahl (Astro- naut Tom Stafford), David Andrews (Frank Borman), Cary Elwes (As- tronaut Michael Collins), Tony Goldwyn (Astronaut Neil Armstrong), Ted Levine (Astronaut Alan Shepard), Brett Cullen (Astronaut Dave Scott), Conor O’Farrell (Astronaut James McDivitt), J. -

I!Iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiilk:,,,,,,,,

ii!i!iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiilk:,,,,,,,,_,,,,,,................ ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::"":'::_:_:i:i'T+:"_:.: iiii!iiiiiiiiiiiii.::'.:ii!iii!i_i!i_i!!_i_i!! ii_:i!',iii!!:i!@ IB (NASA-TM-109852) AN ANNOTATED N94-B_66B BIBLIOGRAPHY _F THE APOLLO PROGRAM (NASA) 105 p Ur}cl as G3/99 001_i01 AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE APOLLO PROGRAM by Roger D. Launius and J. D. Hunley NASA History Office Code ICH NASA Headquarters Washington, DC 20546 MONOGRAPHS IN AEROSPACE HISTORY Number 2 July 1994 AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE APOLLO PROGRAM PREFACE When future generations review the history of the twentieth century they will judge humanity's movement into space, with both machines and people, as one of its most important developments. Even at this juncture the compelling nature of space flight, and the activity that it has engendered on the part of many peoples and governments, makes the U.S. civil space program a significant area of investigation. People from all avenues of experience and levels of education share an interest in, if not always an attraction to, the drama of space flight. No doubt the lunar landing of Apollo 11 in the summer of 1969 is the high point of this continuing drama. Although President John F. Kennedy had made a public commitment in 1961 to land an American on the Moon by the end of the decade, before this time Apollo had been all promise, and now the realization was about to begin. Its success was an enormously significant accomplishment coming at a time when American society was in crisis; if only for a few moments the world united as one to focus on the historic occasion. -

Lunarna Programa Zda in Sovjetske Zveze Ter Njun Vpliv Na Hladno Vojno

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Damjan Mihelič LUNARNA PROGRAMA ZDA IN SOVJETSKE ZVEZE TER NJUN VPLIV NA HLADNO VOJNO Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2004 UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Damjan Mihelič Mentor: doc. dr. Damijan Guštin LUNARNA PROGRAMA ZDA IN SOVJETSKE ZVEZE TER NJUN VPLIV NA HLADNO VOJNO Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2004 1 In ko zapuščamo Luno, jo zapuščamo kot smo prišli in, z Božjo pomočjo, kot se bomo nanjo vrnili, z mi- rom in upanjem za vse človeštvo. GENE CERNAN, APOLLO 17 ZADNJE BESEDE ČLOVEKA NA LUNI, 13. DECEMBER 1972 2 KAZALO I. UVOD ................................................................................................................................... 4 I.1. Uvodna beseda ............................................................................................................... 4 I.2. Opredelitev problema in namen dela ............................................................................. 5 II. METODOLOŠKO-HIPOTETIČNI OKVIR ....................................................................... 6 II.1. Cilji preučevanja........................................................................................................... 6 II.2. Metode preučevanja...................................................................................................... 6 II.3. Hipoteze........................................................................................................................ 7 II.4. Opredelitev temeljnih pojmov ..................................................................................... -

CHAPTER 8: a Contractual Relationship

CHAPTER 8: A Contractual Relationship Through its NASA contracts, the United States Government mobilized a large segment of American industry comparable to that ordinarily achieved only during the exigencies of war. Space, and more specifically the Apollo lunar program, required a massive effort by a fledgling aerospace industry still struggling to find its own identity. NASA grew massively in size and changed markedly in its configuration from a NACA- like and largely passive research organization into a research/development and mission- oriented agency whose primary business became project management and systems engineering. NASA engineers, trained and with experience in the laboratory and test facility, became managers of people. Whereas in war the government generally mobilized the Nation’s resources through conscription, regimentation, and regulation, NASA mobilized the aerospace industry through a contractual relationship. Arnold S. Levine in Managing NASA in the Apollo Era attributes the enormous increase in government contracting after World War II to the basic virtues of contracting out to the private sector, the limitations of formal advertising, and the demand for special skills in the management and integration of complex weapons systems. Contracting allowed the government to tap the technical experience and capabilities available in the private sector, which was not bound by civil service hiring and retention regulations—albeit labor legislation and union contracts certainly had an effect. Moreover, contracting allowed a very real flexibility in work force and budget expenditures. 1 While the government required it, the reality was that through contracting, NASA built a strong and diverse supporting political framework for government-funded space-related programs, and concurrently helped develop a broad-based technological strength throughout the national economy. -

Apollo Program

Apollo program The Apollo program, also known as Project Apollo, was the third United Apollo program States human spaceflight program carried out by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which succeeded in landing the first humans on the Moon from 1969 to 1972. First conceived during Dwight D. Eisenhower's administration as a three-man spacecraft to follow the one-man Project Mercury which put the first Americans in space, Apollo was later dedicated to President John F. Kennedy's national goal of "landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth" by the end of the 1960s, which he proposed in an address to Congress on May 25, 1961. It was the third US human spaceflight program to fly, preceded by the two-man Project Gemini conceived in 1961 to extend spaceflight capability in support of Apollo. Kennedy's goal was accomplished on theApollo 11 mission when astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed their Apollo Lunar Module (LM) on July 20, 1969, and walked on the lunar surface, while Michael Collins Country United States remained in lunar orbit in the command and service module (CSM), and all Organization NASA three landed safely on Earth on July 24. Five subsequent Apollo missions also landed astronauts on the Moon, the last in December 1972. In these six Purpose Manned lunar landing spaceflights, twelve men walked on the Moon. Status completed Program history Apollo ran from 1961 to 1972, with the first manned flight in 1968. It [1] achieved its goal of manned lunar landing, despite the major setback of a Cost $25.4 billion (1973) [2] 1967 Apollo 1 cabin fire that killed the entire crew during a prelaunch test. -

Oral Histories, Command and Service Module

7/1/2019 Show Apache Solr Results in Table Published on dms_public.local.dev (https://historydms.hq.nasa.gov) Show Apache Solr Results in Table Displaying 1 - 18 of 18 Highlight On Summary View Show All Sort Result Set Record Number 30016 Series: ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEWS Document Type: ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEWS Publish_status: Public Approval Status: APPROVED FOR PUBLIC Subject: COHEN, AARON Location: ELECTRONIC DOCUMENT Folder Title: COHEN, AARON - ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW Period Covered: 1972-04-23: APRIL 23, 1972 Description: Oral history interview with Aaron Cohen conducted by Robert Sherrod re Apollo 16 flight and problems with service module propulsion system (SPS); Apollo command module (CM) design changes after Apollo 1 (AS-204) fire; design changes to CM after Apollo 13 accident; and Apollo program crisis management. Name(s) COHEN, AARON SHERROD, ROBERT Topics: APOLLO 16 FLIGHT, APOLLO COMMAND AND SERVICE MODULE (CSM), SPACECRAFT DESIGN, APOLLO 1 [204] FIRE, APOLLO 13 ACCIDENT Access Type: GUEST Updated By: esuckow Last Update: 2019-03-28T12:32:57Z Record Number 30025 Series: ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEWS Document Type: ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEWS Publish_status: Public Approval Status: APPROVED FOR PUBLIC Subject: MYERS, DALE D. Location: ELECTRONIC DOCUMENT Folder Title: MYERS, DALE D. ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW (MARCH 31, 1970) Period Covered: 1970-03-31: MARCH 31, 1970 Description: Oral history interview with Dale Myers conducted by Robert Sherrod for unpublished book on Apollo program. Interview re Apollo 1 (AS-204) fire and its effect on -

Apollo 1 from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Apollo 1 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Apollo 1 (initially designated AS-204) was the first manned mission of the U.S. Apollo manned lunar Apollo 1 (also AS-204) landing program.[1] The planned low Earth orbital test of the Apollo Command/Service Module never made its target launch date of February 21, 1967, because a cabin fire during a launch rehearsal test on January 27 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Launch Complex 34 killed all three crew members—Command Pilot Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom, Senior Pilot Edward H. White II, and Pilot Roger B. Chaffee—and destroyed the Command Module (CM).[1] The name Apollo 1, chosen by the crew, was officially retired by NASA in commemoration of them on Grissom, White, and Chaffee pose in front of their Apollo/Saturn IB space vehicle on the April 24, 1967.[1] launch pad, ten days before a cabin fire that Immediately after the fire, NASA convened the claimed their lives Apollo 204 Accident Review Board to determine Mission type Crewed spacecraft verification the cause of the fire, and both houses of the test United States Congress launched their own committee inquiries to oversee NASA's Operator NASA investigation. During the investigation, a NASA Mission Up to 14 days (planned) internal document citing problems with prime duration Apollo contractor North American Aviation was publicly revealed by then-Senator Walter F. Spacecraft properties Mondale, and became known as the "Phillips Spacecraft CSM-012 Report", embarrassing NASA Administrator James E. Webb, who was unaware of the Spacecraft Apollo Command/Service document's existence, and attracting controversy type Module, Block I to the Apollo program.