Speculative Fiction Fandom and the Discourse of Empathy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printing Printout

[Directory] parent nodes: Merge Merges Merge Chain Setting Jumps Notes Trigun [Across the Sands, Dune Hot sands, hot lead, hot blood. Have the hearts of men have shrivled under this alien sun? Thunder] Red Dead Redemption Generic Western Infamous [Appropriate X-Men Metahumans are rare, discriminated against, and pressed into service if they aren't lynched. Measures] Shadow Ops Marvel DC Incredibles City of Heroes [Capes & Spandex] Teen Titans Super heroes are real, but so are villains, and so are monsters. Young Justice Hero Academia PS238 Heroes Path of Exile [Cast Out] You're an outcast, exile, abandoned child of civilization. Welcome to life outside the Golden Empire. Avernum Last Exile Ring of Red [Conflict Long in Wolfenstein Two peoples, united in war against one another. Coming] Killzone Red Faction Naruto Basilisk Kamigawa [Court of War] Kami and Humans both embroiled in complex webs of conflict. Mononokehime Samurai Deeper Kyo Inuyasha Drakengard It's grim, it's dark, it's got magic, demons, monsters, and corrupt nobles and shit. [Darker Fantasy] Berserk I wish there was a Black Company Jump. Diablo 1&2 Nechronica BLAME [Elan Vital] Everything falls apart, even people. But people can sometimes be put back together. Neir: Automata Biomega WoD Mortals Hellgate: London [Extranormal GURPS Monster Hunter Go hunt these things that would prey upon mankind. Forces] Hellboy F.E.A.R. Princess Bride [Fabled Disney Princess Your classic Princess and Prince Charming. Sort of. Coronation] Shrek Love is a Battlefield Platoon Generation Kill War is hell. There is little honor, little glory to be won on the stinking fields of death between the [Fog of War] WW2 (WIP) trenches. -

IAW 2018 E-Book.Pdf

IT’S ALL WRITE 2018 0 1 Thank you to our generous sponsors: James Horton for the Arts Trust Fund & Loudoun Library Foundation, Inc. Thank you to the LCPL librarians who selected the stories for this book and created the electronic book. These stories are included in their original format and text, with editing made only to font and spacing. 2 Ernest Solar has been a writer, storyteller, and explorer of some kind for his entire life. He grew up devouring comic books, novels, any other type of books along with movies, which allowed him to explore a multitude of universes packed with mystery and adventure. A professor at Mount St. Mary’s University in Maryland, he lives with his family in Virginia. 3 Table of Contents Middle School 1st Place Old Blood ........................................................... 8 2nd Place Hope For Life ................................................. 22 3rd PlaceSad Blue Mountain ......................................... 36 Runner Up Oblivion ...................................................... 50 Runner Up In the Woods ............................................. 64 Middle School Honorable Mentions Disruption ........................................................................ 76 Edge of the Oak Sword ................................................. 84 Perfection .......................................................................... 98 The Teddy ...................................................................... 110 Touch the Sky............................................................... -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

The Cyborg Griffin: a Speculative Literary Journal

Hollins University Hollins Digital Commons Cyborg Griffin: a Speculative Fiction Literary Journal 2014 The yC borg Griffin: ap S eculative Literary Journal Hollins University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/cyborg Part of the Fiction Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Hollins University, "The yC borg Griffin: a Speculative Literary Journal" (2014). Cyborg Griffin: a Speculative Fiction Literary Journal. 3. https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/cyborg/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Hollins Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cyborg Griffin: a Speculative Fiction Literary Journal by an authorized administrator of Hollins Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Volume IV 2014 The Cyborg Griffin A Speculative Fiction Literary Journal Hollins University ©2014 Tributes Editors Emily Catedral Grace Gorski Katharina Johnson Sarah Landauer Cynthia Romero Editing Staff Rachel Carleton AnneScott Draughon Kacee Eddinger Sheralee Fielder Katie Hall Hadley James Maura Lydon Michelle Mangano Laura Metter Savannah Seiler Jade Soisson-Thayer Taylor Walker Kara Wright Special Thanks to: Jeanne Larsen, Copperwing, Circuit Breaker, and Cyberbyte 2 Table of Malcontents Cover Design © Katie Hall Title Page Image © Taylor Hurley The Machine Princess Hadley James ......................................................................................... -

Horse Motifs in Folk Narrative of the Supernatural

HORSE MOTIFS IN FOLK NARRATIVE OF THE SlPERNA TURAL by Victoria Harkavy A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies Committee: ___ ~C=:l!L~;;rtl....,19~~~'V'l rogram Director Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: ~U_c-ly-=-a2..!-.:t ;LC>=-----...!/~'fF_ Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Horse Motifs in Folk Narrative of the Supernatural A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Victoria Harkavy Bachelor of Arts University of Maryland-College Park 2006 Director: Margaret Yocom, Professor Interdisciplinary Studies Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my wonderful and supportive parents, Lorraine Messinger and Kenneth Harkavy. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee, Drs. Yocom, Fraser, and Rashkover, for putting in the time and effort to get this thesis finalized. Thanks also to my friends and colleagues who let me run ideas by them. Special thanks to Margaret Christoph for lending her copy editing expertise. Endless gratitude goes to my family taking care of me when I was focused on writing. Thanks also go to William, Folklore Horse, for all of the inspiration, and to Gumbie, Folklore Cat, for only sometimes sitting on the keyboard. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract .............................................................................................................................. vi Interdisciplinary Elements of this Study ............................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

Japanese Animation Guide: the History of Robot Anime

Commissioned by Japan's Agency for Cultural Affairs Manga, Animation, Games, and Media Art Information Bureau Japanese Animation Guide: The History of Robot Anime Compiled by Mori Building Co., Ltd. 2013 Commissioned by Japan's Agency for Cultural Affairs Manga, Animation, Games, and Media Art Information Bureau Japanese Animation Guide: The History of Robot Anime Compiled by Mori Building Co., Ltd. 2013 Addition to the Release of this Report This report on robot anime was prepared based on information available through 2012, and at that time, with the exception of a handful of long-running series (Gundam, Macross, Evangelion, etc.) and some kiddie fare, no original new robot anime shows debuted at all. But as of today that situation has changed, and so I feel the need to add two points to this document. At the start of the anime season in April of 2013, three all-new robot anime series debuted. These were Production I.G.'s “Gargantia on the Verdurous Planet," Sunrise's “Valvrave the Liberator," and Dogakobo and Orange's “Majestic Prince of the Galactic Fleet." Each was broadcast in a late-night timeslot and succeeded in building fanbases. The second new development is the debut of the director Guillermo Del Toro's film “Pacific Rim," which was released in Japan on August 9, 2013. The plot involves humanity using giant robots controlled by human pilots to defend Earth’s cities from gigantic “kaiju.” At the end of the credits, the director dedicates the film to the memory of “monster masters” Ishiro Honda (who oversaw many of the “Godzilla” films) and Ray Harryhausen (who pioneered stop-motion animation techniques.) The film clearly took a great deal of inspiration from Japanese robot anime shows. -

International Reinterpretations

International Reinterpretations 1 Remakes know no borders… 2 … naturally, this applies to anime and manga as well. 3 Shogun Warriors 4 Stock-footage series 5 Non-US stock-footage shows Super Riders with the Devil Hanuman and the 5 Riders 6 OEL manga 7 OEL manga 8 OEL manga 9 Holy cow, more OEL manga! 10 Crossovers 11 Ghost Rider? 12 The Lion King? 13 Godzilla 14 Guyver 15 Crying Freeman 16 Fist of the North Star 17 G-Saviour 18 Blood: the Last Vampire 19 Speed Racer 20 Imagi Studios 21 Ultraman 6 Brothers vs. the Monster Army (Thailand) The Adventure Begins (USA) Towards the Future (Australia) The Ultimate Hero (USA) Tiga manhwa 22 Dragonball 23 Wicked City 24 City Hunter 25 Initial D 26 Riki-Oh 27 Asian TV Dramas Honey and Clover Peach Girl (Taiwan) Prince of Tennis (Taiwan) (China) 28 Boys Over Flowers Marmalade Boy (Taiwan) (South Korea) Oldboy 29 Taekwon V 30 Super Batman and Mazinger V 31 Space Gundam? Astro Plan? 32 Journey to the West (Saiyuki) Alakazam the Great Gensomaden Saiyuki Monkey Typhoon Patalliro Saiyuki Starzinger Dragonball 33 More “Goku”s 34 The Water Margin (Suikoden) Giant Robo Outlaw Star Suikoden Demon Century Akaboshi 35 Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sangokushi) Mitsuteru Yokoyama’s Sangokushi Kotetsu Sangokushi BB Senshi Sangokuden Koihime Musou Ikkitousen 36 World Masterpiece Theater (23 seasons since 1969) Moomin Heidi A Dog of Flanders 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother Anne of Green Gables Adventures of Tom Sawyer Swiss Family Robinson Little Women Little Lord Fauntleroy Peter -

The Mobile Suit Gundam Franchise

The Mobile Suit Gundam Franchise: a Case Study of Transmedia Storytelling Practices and the Role of Digital Games in Japan Akinori (Aki) Nakamura College of Image Arts and Sciences, Ritsumeikan University 56-1 Toji-in Kitamachi, Kita-ku, Kyoto 603-8577 [email protected] Susana Tosca Department of Arts and Communication, Roskilde University Universitetsvej 1, P.O. Box 260 DK-4000 Roskildess line 1 [email protected] ABSTRACT The present study looks at the Mobile Suit Gundam franchise and the role of digital games from the conceptual frameworks of transmedia storytelling and the Japanese media mix. We offer a historical account of the development of “the Mobile Suit Gundam” series from a producer´s perspective and show how a combination of convergent and divergent strategies contributed to the success of the series, with a special focus on games. Our case can show some insight into underdeveloped aspects of the theory of transmedial storytelling and the Japanese media mix. Keywords Transmedia Storytelling, Media mix, Intellectual Property, Business Strategy INTRODUCTION The idea of transmediality is now more relevant than ever in the context of media production. Strong recognizable IPs take for example more and more space in the movie box office, and even the Producers Guild of America ratified a new title “transmedia producer” in 2010 1. This trend is by no means unique to the movie industry, as we also detect similar patterns in other media like television, documentaries, comics, games, publishing, music, journalism or sports, in diverse national and transnational contexts (Freeman & Gambarato, 2018). However, transmedia strategies do not always manage to successfully engage their intended audiences; as the problematic reception of a number of works can demonstrate. -

Helden. Heroes. Héros. 2

1 Animals: Projecting the Heroic helden. across Species Entangled Agency: Heroic Dragons and Direwolves in Game of Thrones Stefanie Lethbridge heroes. Dogs and Horses as Heroes: Animal (Auto)Biographies in England, 1751-1800 Angelika Zirker Die Heroisierung von Kriegspferden und ihre Funktion im Hinblick auf héros. Heroisierungsprozesse in der mili- tärischen Erinnerungskultur der Napoleonischen Kriege im 19. Jahrhundert E-Journal Kelly Minelli “Famous”, “Immortal” – and zu Kulturen Heroic? The White Whale as Hero in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick des Heroischen. Klara Stephanie Szlezák Widerspruch mit der Zunge einer Hündin. Tierlicher Antiheroismus in Blondi von Michael Degen Tina Hartmann Animal Survival and Inter-Species Heroism in Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man Tom Chadwick Können Tiere Helden sein? Anthropozentrischer und zoozentrischer Anthropomorphismus in Gabriela Cowperthwaites Blackfish Claudia Lillge Edited by Marie-Luise Egbert and Ulrike Zimmermann Volume 3 (2018) Special Issue helden. heroes. héros. 2 Contents Editorial Marie-Luise Egbert and Ulrike Zimmermann . 3 Entangled Agency: Dragons and Direwolves in Game of Thrones Stefanie Lethbridge . 7 Dogs and Horses as Heroes: Animal (Auto)Biographies in England, 1751-1800 Angelika Zirker . 17 „God’s humbler instrument of meaner clay, must share the honours of that glorious day .“ Die Heroisierung von Kriegspferden und ihre Funktion im Hinblick auf Heroisierungsprozesse in der militärischen Erinnerungskultur der Napoleonischen Kriege im 19 . Jahrhundert Kelly Minelli . 27 “Famous”, “Immortal” – and Heroic? The White Whale as Hero in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick Klara Stephanie Szlezák . 41 Widerspruch mit der Zunge einer Hündin . Tierlicher Antiheroismus in Blondi von Michael Degen Tina Hartmann . 49 “Let’s have some fucking water for these animals .” Animal Survival and Inter-Species Heroism in Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man Tom Chadwick . -

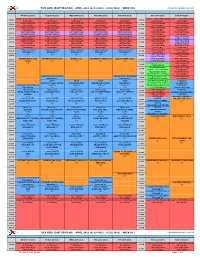

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

Atlantic News

This Page © 2004 Connelly Communications, LLC, PO Box 592 Hampton, NH 03843- Contributed items and logos are © and ™ their respective owners Unauthorized reproduction 30 of this page or its contents for republication in whole or in part is strictly prohibited • For permission, call (603) 926-4557 • AN-Mark 9A-EVEN- Rev 12-16-2004 PAGE 4 SEA | ATLANTIC NEWS | JUNE 16, 2006 | VOL 32, NO 23 ATLANTICNEWS.COM . Brentwood | East Kingston | Exeter | Greenland | Hampton | Hampton Beach | Hampton Falls | Kensington | Newfields | North Hampton | Rye | Rye Beach | Seabrook | South Hampton | Stratham MAILED WEEKLY TO NEARLY 23,000 HOMES!! POSITIVE COMMUNITY AND SCHOOL NEWS FROM 15 TOWNS ATLANTIC LOCALLY OWNED WITH AN INDEPENDENT VOICE 5 TIMES THE REACH AT LESS THAN HALF THE COMPETITORS’ RATE! NEWS To Advertise Call PRICELESS! MIchelle or Sheri at (603) 926-4557 6/17/06 5 PM 5:30 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 WBZ-4 Intercontinental Pok- News CBS Entertainment CSI: NY “Super Men” 48 Hours Mystery “Written in Blood” ’ News (:35) The (12:05) Da Vinci’s In- (CBS) er Champ. (CC) News Tonight (N) ’ (CC) ’ (HD) (CC) (CC) Insider quest (CC) WCVB-5 Explo- Ebert & News ABC Wld 24 “Day 2: 9:00 - ››› Lady and the Tramp (1955) (HD) Voic- The Evidence “Wine News (:35) Star Trek: En- Home- (ABC) ration Roeper (CC) News 10:00PM” ’ (CC) es of Peggy Lee. ’ (CC) and Die” (N) (CC) terprise “Home” ’ Team (N) WCSH-6 Golf U.S.