The Mobile Suit Gundam Franchise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printing Printout

[Directory] parent nodes: Merge Merges Merge Chain Setting Jumps Notes Trigun [Across the Sands, Dune Hot sands, hot lead, hot blood. Have the hearts of men have shrivled under this alien sun? Thunder] Red Dead Redemption Generic Western Infamous [Appropriate X-Men Metahumans are rare, discriminated against, and pressed into service if they aren't lynched. Measures] Shadow Ops Marvel DC Incredibles City of Heroes [Capes & Spandex] Teen Titans Super heroes are real, but so are villains, and so are monsters. Young Justice Hero Academia PS238 Heroes Path of Exile [Cast Out] You're an outcast, exile, abandoned child of civilization. Welcome to life outside the Golden Empire. Avernum Last Exile Ring of Red [Conflict Long in Wolfenstein Two peoples, united in war against one another. Coming] Killzone Red Faction Naruto Basilisk Kamigawa [Court of War] Kami and Humans both embroiled in complex webs of conflict. Mononokehime Samurai Deeper Kyo Inuyasha Drakengard It's grim, it's dark, it's got magic, demons, monsters, and corrupt nobles and shit. [Darker Fantasy] Berserk I wish there was a Black Company Jump. Diablo 1&2 Nechronica BLAME [Elan Vital] Everything falls apart, even people. But people can sometimes be put back together. Neir: Automata Biomega WoD Mortals Hellgate: London [Extranormal GURPS Monster Hunter Go hunt these things that would prey upon mankind. Forces] Hellboy F.E.A.R. Princess Bride [Fabled Disney Princess Your classic Princess and Prince Charming. Sort of. Coronation] Shrek Love is a Battlefield Platoon Generation Kill War is hell. There is little honor, little glory to be won on the stinking fields of death between the [Fog of War] WW2 (WIP) trenches. -

The Anime Galaxy Japanese Animation As New Media

i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i Herlander Elias The Anime Galaxy Japanese Animation As New Media LabCom Books 2012 i i i i i i i i Livros LabCom www.livroslabcom.ubi.pt Série: Estudos em Comunicação Direcção: António Fidalgo Design da Capa: Herlander Elias Paginação: Filomena Matos Covilhã, UBI, LabCom, Livros LabCom 2012 ISBN: 978-989-654-090-6 Título: The Anime Galaxy Autor: Herlander Elias Ano: 2012 i i i i i i i i Índice ABSTRACT & KEYWORDS3 INTRODUCTION5 Objectives............................... 15 Research Methodologies....................... 17 Materials............................... 18 Most Relevant Artworks....................... 19 Research Hypothesis......................... 26 Expected Results........................... 26 Theoretical Background........................ 27 Authors and Concepts...................... 27 Topics.............................. 39 Common Approaches...................... 41 1 FROM LITERARY TO CINEMATIC 45 1.1 MANGA COMICS....................... 52 1.1.1 Origin.......................... 52 1.1.2 Visual Style....................... 57 1.1.3 The Manga Reader................... 61 1.2 ANIME FILM.......................... 65 1.2.1 The History of Anime................. 65 1.2.2 Technique and Aesthetic................ 69 1.2.3 Anime Viewers..................... 75 1.3 DIGITAL MANGA....................... 82 1.3.1 Participation, Subjectivity And Transport....... 82 i i i i i i i i i 1.3.2 Digital Graphic Novel: The Manga And Anime Con- vergence........................ 86 1.4 ANIME VIDEOGAMES.................... 90 1.4.1 Prolongament...................... 90 1.4.2 An Audience of Control................ 104 1.4.3 The Videogame-Film Symbiosis............ 106 1.5 COMMERCIALS AND VIDEOCLIPS............ 111 1.5.1 Advertisements Reconfigured............. 111 1.5.2 Anime Music Video And MTV Asia......... -

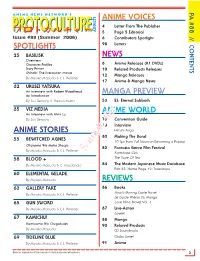

Protoculture Addicts

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

Banshee Gundam Review by Ziggy Downs-Bumgardner

December 2018 AUSTIN SCALE MODELERS SOCIETY Banshee Gundam Review By Ziggy Downs-Bumgardner FJ-3 Fury Reviewed by Ron McCracken Milleniumcon! • On The Table Texas’ Biggest Historical • Old Rumors and New Kits Miniature Wargame Convention • The Cotton Report GREEN MONKEY ‘Thumbs-Up’ NewsNews •• ArticlesArticles •• FeaturesFeatures •• OpinionsOpinions •• AdviceAdvice •• HumbugHumbug sign of approval ASMS Sprue examiner December 2018 Our Sponsors Page 3 The President’s Notepad – By Aaron Smischney Page 4 Mobile Suit RX-O Unicorn Gundam 02 Banshee Review – By Ziggy Downs-Bumgardner www.austinarmorbuilders.com Page 9 Sword’s 1/72nd FJ-3 Fury - By Ron McCracken Page 12 The Cotton Report: Winter is coming… - By Rick Cotton Page 14 On The Table - by Flanged End Yoke www.kingshobbyshop.com Page 17 Old Rumors and New Kits: Page 17 Shipping News – by Rick Herrington Page 19 The Air Report – by Ron McCracken www.wmbros.com Page 21 It Figures – by Michael Lamm Page 26 Tracked Topics – by Rick Herrington Page 29 Sundries - Golzar Shahrzàd Page 33 Milleniumcon - by Rick Herrington www.ctsms.org Phil Brandt (in memorium) Austin Scale Modelers Society (ASMS) is a chartered chapter of International Plastic Modelers Society (IPMS/ Eric Choy Angela Forster USA). ASMS meets on the third Thursday of each month. Jeff Forster Russ Holm Anual dues for full membership are $25/individual or $30/ Rick Willaman Jack Johnston family. The views expressed in this newsletter are those of Mike Krizan Rick Herrington the authors. It is intended for educational purposes only. Aaron Smischney www.austinsms.org ASMS does not endorese the contents of any article. -

Anime Expo Lite 2021 Sweepstakes Official Rules

ANIME EXPO LITE 2021 SWEEPSTAKES OFFICIAL RULES 1. Official Rules. The Anime Expo Lite 2021 Sweepstakes (the “Promotion”) is subject to these Official Rules, except as expressly stated otherwise. No purchase necessary. A purchase does not improve your chances of winning. Void where prohibited. The Sweepstakes is sponsored by Society for the Promotion of Japanese Animation, 1522 Brookhollow Dr. Suite 1, Santa Ana, CA 92705 (the “Sponsor”). 2. Eligibility. The Sweepstakes is open to legal residents of the United States (but excluding U.S. military installations in foreign countries and all other U.S. territories and possessions), who are 18 years of age or older at the start of the Promotion (“Entrant”). By participating in the Sweepstakes, Entrant agrees to be fully and unconditionally bound by these Official Rules and the decisions of Sponsor. 3. Privacy. The information you provide in your entry will be used for administering this Promotion and for marketing purposes in accordance with Sponsor’s privacy policy found here: http://www.anime-expo.org/plan/policies/. 4. Sweepstakes Period. The Sweepstakes begins at 12:00 p.m PDT on June 25, 2021 and ends at 12:00 p.m. PDT on July 16, 2021 (the "Promotion Period"). 1. How to Enter the Sweepstakes. During the Sweepstakes Period, you can enter the Sweepstakes through the following methods: a. Purchase: You may purchase an online pass for Anime Expo Lite 2021 from https://www.tixr.com/groups/animeexpolite/events/anime-expo-lite-2021- benefitting-hate-is-a-virus-23015 (“Website”); Note: All online passes purchased prior to the Sweepstakes Period are also eligible to enter. -

Event Highlights

Event Highlights Events • Yoshihiro Ike: Anime Soundtrack World sponsored by Studio Kitchen: International debut performance of one of Japan’s most prolific music composers in the industry featuring a 50 piece orchestra that will bring to life the greatest collection of soundtracks from Tiger & Bunny, Saint Seiya, B: The Beginning, Dororo, Rage of Bahamut:Genesis, and Shadowverse. • 4DX Anime Film Festival: Featuring Detective Conan: Zero The Enforcer, Mobile Suit Gundam NT (Narrative) and Mobile Suit Gundam 00 the MOVIE – A Wakening of the Trailblazer- enhanced with immersive, multi-sensory 4DX motion and environmental effects. • Anime Expo Masquerade & World Cosplay Summit US Finals • Inside the World of Street Fighter & Street Fighter V: Arcade Edition - Ultimate Cosplay Showdown sponsored by Capcom • LOVE LIVE! SUNSHINE!! Aqours World LoveLive! in LA ~BRAND NEW WAVE~ • Fate/Grand Order USA Tour • Fashion Show: Featuring Japanese brands h. NAOTO with designer Hirooka Naoto, Acryl CANDY with guest model Haruka Kurebayashi, amnesiA¶mnesiA with guest model Yo from Matenrou Opera, and Metamorphose with designer Chinatsu Taira. In addition, Hot Topic will reveal a new collection and HYPLAND will debut new items from their BLEACH collaboration. Programming • 15+ Premieres & Exclusive Screenings: Promare, Dr. Stone, In/Spectre, Human Lost, Fire Force, My Hero Academia Season 4, “Pokémon: Mewtwo Strikes Back—Evolution!” and more. • 900+ Hours of Panels, Events, Screenings, Workshops, and more. • Programming Tracks: Career, Culture, Family, and Academic Program. • Pre-Show Night on July 4 (6 - 10pm) 150+ Guests & Industry Appearances • Creators: Katsuhiro Otomo, Bisco Hatori, Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, Yusuke Kozaki, Atsushi Ohkubo, Utako Yukihiro. • Japanese Voice Actors: Rica Matsumoto, Mamoru Miyano, Maya Uchida, Kaori Nazuka. -

11Eyes Achannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air

11eyes AChannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air Master Amaenaideyo Angel Beats Angelic Layer Another Ao No Exorcist Appleseed XIII Aquarion Arakawa Under The Bridge Argento Soma Asobi no Iku yo Astarotte no Omocha Asu no Yoichi Asura Cryin' B Gata H Kei Baka to Test Bakemonogatari (and sequels) Baki the Grappler Bakugan Bamboo Blade Banner of Stars Basquash BASToF Syndrome Battle Girls: Time Paradox Beelzebub BenTo Betterman Big O Binbougami ga Black Blood Brothers Black Cat Black Lagoon Blassreiter Blood Lad Blood+ Bludgeoning Angel Dokurochan Blue Drop Bobobo Boku wa Tomodachi Sukunai Brave 10 Btooom Burst Angel Busou Renkin Busou Shinki C3 Campione Cardfight Vanguard Casshern Sins Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Chaos;Head Chobits Chrome Shelled Regios Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai Clannad Claymore Code Geass Cowboy Bebop Coyote Ragtime Show Cuticle Tantei Inaba DFrag Dakara Boku wa, H ga Dekinai Dan Doh Dance in the Vampire Bund Danganronpa Danshi Koukousei no Nichijou Daphne in the Brilliant Blue Darker Than Black Date A Live Deadman Wonderland DearS Death Note Dennou Coil Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko Densetsu no Yuusha no Densetsu Desert Punk Detroit Metal City Devil May Cry Devil Survivor 2 Diabolik Lovers Disgaea Dna2 Dokkoida Dog Days Dororon EnmaKun Meeramera Ebiten Eden of the East Elemental Gelade Elfen Lied Eureka 7 Eureka 7 AO Excel Saga Eyeshield 21 Fight Ippatsu! JuudenChan Fooly Cooly Fruits Basket Full Metal Alchemist Full Metal Panic Futari Milky Holmes GaRei Zero Gatchaman Crowds Genshiken Getbackers Ghost -

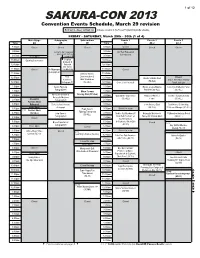

Sakura-Con 2013

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST 320Kbpsrar

Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST 320kbpsrar Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST 320kbpsrar 1 / 3 2 / 3 Download FLAC Gundam Seed - Seed Complete Best 2004 lossless CD, MP3, M4A. Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST [320kbps].rar Gundam .... Mobile Suit Gundam SEED is an anime series developed by Sunrise and directed by Mitsuo ... The Archangel arrives in Alaska but ZAFT launches a full-scale attack on the base overpowering their enemies. ... Mobile Suit Gundam SEED ~ SEED DESTINY BEST "THE BRIDGE" Across the Songs from GUNDAM SEED .... Jump to Mobile Suit Gundam SEED Complete Best - Mobile Suit Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST. Compilation album by. T.M.Revolution, See- Saw, .... View credits, reviews, tracks and shop for the 2004 CD release of Mobile Suit Gundam Seed Complete Best on Discogs.. Jump to Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST 320kbpsrar - tercardmitrue - All Gundam Seed + Destiny Opening ... Best* Title: Gundam 00 Complete Best Type OST: .... Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST [320kbps].rar ... http://www.mediafire.com/file/796jpbeqq39ny68/amd-hh full moon paper & qp.zip.. Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST [320kbps].rar DOWNLOAD. 5f91d47415 Music of Mobile Suit Gundam SEED - WikipediaMusic of Mobile .... This cd has all the songs from the anime and is very enjoyable. The songs are longer than the anime openings, but are still very enjoyable and fun to listen to.. Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST [320kbps].rar >> http://urllio.com/rwc1z 89e59902e3.. Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST [320kbps].rarhttp://bltlly.com/11tes0.. Album: Mobile Suit Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST (機動戦士ガンダムSEED COMPLETE BEST); Released: 2003.09.26; Catalog Number: AICL-1489~90 ... 54ea0fc042 Windows Vista Crack Product 21 Mettle Freeform Pro Mac Crack 20 Diamond Necklace Full Movie Free Download gilad hekselman transcription pdf download Falkovideo 86 kenneth laudon sistemas de informacion gerencial pdf download Hassan Sadiq Qasida Mp4 Free Download Skold Skold Rar conant gardens maschine serial 14 Hindi Medium 2 full movie download in 720p hd 3 / 3 Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST 320kbpsrar. -

Japanese Animation Guide: the History of Robot Anime

Commissioned by Japan's Agency for Cultural Affairs Manga, Animation, Games, and Media Art Information Bureau Japanese Animation Guide: The History of Robot Anime Compiled by Mori Building Co., Ltd. 2013 Commissioned by Japan's Agency for Cultural Affairs Manga, Animation, Games, and Media Art Information Bureau Japanese Animation Guide: The History of Robot Anime Compiled by Mori Building Co., Ltd. 2013 Addition to the Release of this Report This report on robot anime was prepared based on information available through 2012, and at that time, with the exception of a handful of long-running series (Gundam, Macross, Evangelion, etc.) and some kiddie fare, no original new robot anime shows debuted at all. But as of today that situation has changed, and so I feel the need to add two points to this document. At the start of the anime season in April of 2013, three all-new robot anime series debuted. These were Production I.G.'s “Gargantia on the Verdurous Planet," Sunrise's “Valvrave the Liberator," and Dogakobo and Orange's “Majestic Prince of the Galactic Fleet." Each was broadcast in a late-night timeslot and succeeded in building fanbases. The second new development is the debut of the director Guillermo Del Toro's film “Pacific Rim," which was released in Japan on August 9, 2013. The plot involves humanity using giant robots controlled by human pilots to defend Earth’s cities from gigantic “kaiju.” At the end of the credits, the director dedicates the film to the memory of “monster masters” Ishiro Honda (who oversaw many of the “Godzilla” films) and Ray Harryhausen (who pioneered stop-motion animation techniques.) The film clearly took a great deal of inspiration from Japanese robot anime shows. -

Bandai June New Product

Bandai June New Product ZZ II "Gundam Build Fighters", Bandai HGBF 1/144 Launching alongside the release of a new Gundam Build Fighters Try episode, the popular Z II is now available! Capable of transforming into its Wave Rider form, the model kit also comes with powerful large-scale weaponry. Set includes a large beam rifle, transformation replacement parts, and interchangeable hand. Runner x12. Foil Sticker x1. Instruction manual x1. Approximately 5.5" Tall Package Size: Approximately 12.2"x7.8"x3.1" MSRP: $27.99 Gyancelot "Gundam Build Fighters", Bandai HGBF 1/144 From the Gyan family, comes a new model kit featuring Gyancelot! With expert detailing on the shield and weapons, the color scheme and textures accurately reproduces the look from the anime! The large lance appears in the shape of the crest of the Principality of Zeon, and its blades can be opened or closed through the use of replacement parts. Set includes large lance, beam saber, shield, and interchangeable hands. Runner x11. Foil sticker x1. Instruction manual x1. Approx. 5" Tall Package Size: Approx. 11.7"x7.4"x3.0" MSRP: $19.99 Gya Eastern Weapons "Gundam Build Fighters", Bandai HGBC 1/144 This is a kit focusing on parts for hand-held weapons from the Build Custom series! The parts can be used to customize existing models from various 1/144 series. The large rifle from the HG 1/144 ZZ II can be combined with a newly molded clay bazooka and optional parts for the lance from the Gyancelot can be customized as well. -

Continuing to Innovate with a Focus on Global Business Initiatives Aligned with Changes in Our Markets

NEWSLETTER September 2018 BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. BANDAI NAMCO Mirai-Kenkyusho 5-37-8 Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-0014 Mitsuaki Taguchi Interview with the President President & Representative Director, BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. Continuing to innovate with a focus on global business initiatives aligned with changes in our markets Under the Mid-term Plan, the Group announced a mid-term vision of CHANGE for the NEXT — Empower, Gain Momentum, and Accelerate Evolution, and launched a five-Unit system. In the first quarter, the Group achieved record-high sales. In these ways, the Mid-term Plan has gotten off to a favorable start. In this issue of the newsletter, BANDAI NAMCO Holdings’ President Mitsuaki Taguchi discusses the future results forecast and the situation with each of the Group’s Units. How were the results in the first What is the outlook for the future? for the mature fan base, BANDAI SPIRITS quarter? Taguchi: In our industry, the environment is CO., LTD., a new company that consolidates Taguchi: In the first quarter of FY2019.3, in undergoing drastic changes, and it is difficult the mature fan base business of the Toys and comparison with the same period of the previous to forecast all of the future trends based on Hobby Unit, started fullscale operation. With year, each business recorded favorable overall three months of results. Considering bolstered a separate organizational structure and a clarified progress with core IP* and products/services, marketing and promotion for businesses mission, the sense of speed in this business despite differences in the home video game recording favorable results; recent business has increased.