Artists in Dialogue Creative Approaches to Interreligious Encounters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EWVA 4Th Full Proofxx.Pdf (9.446Mb)

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk Faculty of Arts and Humanities School of Art, Design and Architecture 2019-04 Ewva European Women's Video Art in The 70sand 80s http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/16391 JOHN LIBBEY PUBLISHING All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. EWVA EuropeanPROOF Women’s Video Art in the 70s and 80s do not distribute PROOF do not distribute Cover image: Lydia Schouten, The lone ranger, lost in the jungle of erotic desire, 1981, still from video. Courtesy of the artist. EWVA European Women’s PROOF Video Art in the 70s and 80s Edited by do Laura Leuzzi, Elaine Shemiltnot and Stephen Partridge Proofreading and copyediting by Laura Leuzzi and Alexandra Ross Photo editing by Laura Leuzzi anddistribute Adam Lockhart EWVA | European Women's Video Art in the 70s and 80s iv British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data EWVA European Women’s Video Art in the 70s and 80s A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 9780 86196 734 6 (Hardback) PROOF do not distribute Published by John Libbey Publishing Ltd, 205 Crescent Road, East Barnet, Herts EN4 8SB, United Kingdom e-mail: [email protected]; web site: www.johnlibbey.com Distributed worldwide by Indiana University Press, Herman B Wells Library – 350, 1320 E. -

If One Were to Describe European Dance Since the 1990S in Geopolitical Terms, It Would Be a Disintegration of the Center and Dispersion Toward New Cells

2005.12.28 If one were to describe European dance since the 1990s in geopolitical terms, it would be a disintegration of the center and dispersion toward new cells. While on the one hand we see a continuing diversification of expression, we are also seeing the start of trend toward similarity in the creative approach and ideas due to the development of information networks and media. The creators are questioning the fundamental elements of “creativity” as the source of creation. Within this context, there was widespread critical acclaim when the Lyon Dance Biennial 2004 chose a program consisting primarily of artists from what had until recently had been considered the peripheral regions of Eastern Europe, Scandinavia and the Mediterranean countries rather than the “mainstream” countries of France and Germany. This move was considered an apt reflection of present conditions. In fact, there is increasing attention coming to focus today on the refreshing new expressions coming out of these areas of Eastern Europe, Scandinavia and the Mediterranean countries, which are indeed possessed of new, untapped appeal. Among these up and coming dance nations, Finland has shown especially vital growth in recent years. It is dance that is energetic and strong-boned or, you would not call it stylish or adroit, but it stands out among the dance styles of Europe with a unique vibrancy that draws from an accentuated presence of the body. For example, among the performances I saw during the 2005 season, the one that perhaps left the strongest impression was Borrowed Light by one of Finland’s representative choreographers, Tero Saarinen. -

Nordic Wildlife. Norwegian Seattle. a Filmmaker in Iceland

WHAT THE GREENLAND VIKINGS CAN TEACH US ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE. SPRING 2009 Volume 16: Issue 2 www.nordicway.com $395 Nordic Wildlife. Norwegian Seattle. A Filmmaker In Iceland. PM 40010214 R9201 Now with search engine THE ORIGINAL SWEDISH PRESS APRON Great at the BBQ! Show off your heritage with this unisex navy blue apron with three BIG &BIG and small. large ebroidered golden crowns The BIG BAG is really a very VERY large The BIG bag is a VERYsmall large 32” x 14” x 14” navy blue canvas carry-all and a practical pocket for $29 (All with34”x14”x14” the three navy yellow blue heavycrowns duty for canvas US$29 carry-allor Can$ 43with (Subscribers inside zippered pay pocketUS$27 $ $ subscribers take 10% off) + 10 for orand Can the $three41). Theyellow Small crowns bag for is 39.a practical The small 18” bag xis 9”a neat x 9” 18”x9”x9” navy blue navy nylon blue $ shipping & handling. carry-on with shoulder strap, zippered pocket and the$ three yellow$ crowns for 29. carry-on with the three yellow crowns for US 15$ or Can 22 (subscribers To order simply send a check or your (All subscribers$ take $10% off these prices). Please add$ 10 for shipping & handling VISA or M/C information to Swedish pay US 14 or Can$ 21).$ Shipping & handling$ 5 $per bag. These Original$ Swedishfor orders Press up to 60 (and 12 for orders above 60 and 15 for orders above 100)). Press, Box 4302, Blaine, WA 98230, USA quality bags are sturdy, practical and always recognizable. -

LARS SWANLJUNG Keräilijä Ja Hänen Kokoelmansa Samlaren Och Hans Samling Collector and His Collection Sisältö Innehåll Contents

LARS SWANLJUNG Keräilijä ja hänen kokoelmansa Samlaren och hans samling Collector and His Collection Sisältö Innehåll Contents Tekijänoikeus ja hyvät tavat PAMELA ANDERSSON: JULIA SVARVAR: Upphovsrätt och god ton Rei’itetyt muistot Valta, sukupuoli ja normit Good manners according to Finnish copyright policy 3 Perforerade minnen Makt, kön och normer Perforated Memories 26 Power, Gender and Norms 38 MAARIA NIEMI: Taiteenkeräilijä Lars Swanljungin kokoelma on järjestyksen ja ANNE-KARIN FURUNES LAURA LILJA hulluttelun cocktail Konstsamlaren Lars Swanljungs samling är en cocktail av PIA TIMBERG: PIA TIMBERG: ordning och tokeri 4 Muistatko? – Martti Jämsän valokuvataide Sofia Wilkmanin vapaus Art Collector Lars Swanljung’s Collection is a Cocktail of Order Minns du? – Martti Jämsäs fotokonst Sofia Wilkmans frihet and Foolery Do You Remember? – The Photographic Art of Martti Jämsä 28 The Freedom of Sofia Wilkman 40 PIA TIMBERG: MARTTI JÄMSÄ SOFIA WILKMAN Lars Swanljung – taidekeräilijän elämä Lars Swanljung – en konstsamlares liv 14 MAARIA NIEMI: JULIA SVARVAR: Lars Swanljung – The Life of an Art Collector Ambitious bitch Marita Liulia Performanssia, happeningeja ja liitutaulu 30 Performance, happening och svarta tavlan MAARIA NIEMI: MARITA LIULIA Performance, Happening and Blackboard 42 Islantilainen nykytaide luo perustan Isländsk samtidskonst bildar samlingens grundval MAARIA NIEMI: ROI VAARA The Foundation: Contemporary Art from Iceland 18 Ekspressionistit uskottavuuden mittarina Expressionister som trovärdighetens mätare MAARIA NIEMI: GEORG -

Ambitious Bitch Looks Very Rich - in Texture, Presentation, Content and Style

a m b itio u s lb o U c h in the press La navigation et l'interface sont originales : le sommaire se transforme au fur et à mesure que Ion progresse dans le CD-ROM, des portes colorées s'ouvrent pour que l'on s'y engouffre. L'interactivité apparaiît omniprésente. Agnès Batifoulier / Le Monde 27-28/10/96 Ambitious Bitch looks very rich - in texture, presentation, content and style. ...Marita eviscerates the bowels of multimedia tecknowhow and post-feminism - making it fun, funky and lime- green fresh! Geekgirl 6/96 The program uses English and French but is deeply Finnish: assertive, deceptively simple and technologically advanced. ...a sort of computer game with attitude. Sara Henley/Bangkok Post Jan/96 ...an imposing example of the alliance between intellect and the senses, a sort of sensual orgy in which sounds, colours and words are woven together. ...a Pandora's box, full of surprises. One of the most exciting and provocating CD-ROMs I have seen... Ana Valdes / Dagens Nyheter 7/3/96 AB is a refreshing and non-threatening introduction at the possibilities of CD-ROM, as a media for artistic expression. Lionel Dersot / Cd-Rom Fan, Japan 8/96 The visualisation, design and colours are closely linked to the codes and logos of popular culture, up to the techno and ambient style font-choises. Springier 2/96 f j t k k e t Gc.t, Q fh /9^Q » » I rtCF^OW -ÖOftlf O Ö ^ £ r Ä + $ n U I #4 X - m ; * * - z »□RVf^SlHQffaffi »‘sm & m o M -a víft .»Urd^VUiVA © W rlo ^n ^^ä ^iVASçv(?§]ti!î ¡M fe .dW i^äia vj 0t >Ja Si- sjMa Ss> .» r4^^n; - >j &IdT^-~VrV-V*$ 4^r"^0 I (œ) -iK'lXVSlJ üDtíí (“ '“ ifl S iiO n^.Q S ,GVF: 4^W>rírá9«-m G ^JSrKTr^-^i OOOi IS'd ■Pc:S!> o Ô ^ d 0 & n -sV U iV -w J V îM a 4 |tV ï . -

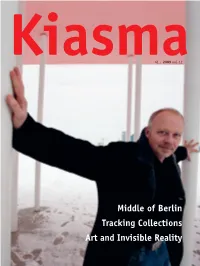

Middle of Berlin Tracking Collections Art and Invisible Reality Art and Invisible Reality

41 · 2009 vol. 12 Middle of Berlin Tracking Collections Art and Invisible Reality Art and Invisible Reality Marita Liulia’s exhibition Choosing My Religion brings religious themes and symbolic imagery to the fifth floor of Kiasma. Liulia has studied the religions of the world in depth and has been presenting the results in the form of art for several years. Metropolitan Ambrosius from the Helsinki diocese of the Finnish Orthodox Church discusses the relationship between art and religion before the exhibition opens. © MARITA LIULIA © MARITA Marita Liulia CHOOSING MY RELIGION Christianity: Assisi series (turquoise), 2008 detail of the new millennium. Another mega- trend Naisbitt mentioned was art. Met- ropolitan Ambrosius sees art as a superb vehicle for depicting the invisible reality. “The Orthodox church has throughout history used the expressive potential of art. Where the church in the West has tended to use written and spoken words and logical argumentation, the church in the East has used images and drama and music.” He looks forward with inter- est to what connections and contrasts the exhibition will present about the dialogue between our ‘European’ religion and the religions of the East. DISCUSSIONS AND ENCOUNTERS Metropolitan Ambrosius considers dis- cussion to be one of the key tasks of contemporary art. Art can “help us enter into dialogue and become aware and see more, to see more deeply, to hear more and thereby to understand ourselves more holistically and to identify our own black holes”. The meeting of art and reli- gion in Kiasma is particularly exciting. “Our European religion is so thoroughly purged of all invisible reality. -

25 Years of Ars Electronica

Literature: Winners in the film section – Computer Animation – Visual Effects Literature: Literature : Literature: Literature (2) : Literature: Literature (2) : Blick, Stimme und (k)ein Körper – Der Einsatz 1987: John Lasseter, Mario Canali, Rolf Herken Cyber Society – Mythos und Realität der Maschinen, Medien, Performances – Theater an Future cinema !! / Jeffrey Shaw, Peter Weibel Ed. Gary Hill / Selected Works Soundcultures – Über elektronische und digitale Kunst als Sendung – Von der Telegrafie zum der elektronischen Medien im Theater und in 1988: John Lasseter, Peter Weibel, Mario Canali and Honorary Mentions (right) Informationsgesellschaft / Achim Bühl der Schnittstelle zu digitalen Welten / Kunst und Video / Bettina Gruber, Maria Vedder Intermedialität – Das System Peter Greenaway Musik / Ed. Marcus S. Kleiner, A. Szepanski 25 years of ars electronica Internet / Dieter Daniels VideoKunst / Gerda Lampalzer interaktiven Installationen / Mona Sarkis Tausend Welten – Die Auflösung der Gesellschaft Martina Leeker (Ed.) Yvonne Spielmann Resonanzen – Aspekte der Klangkunst / 1989: Joan Staveley, Amkraut & Girard, Simon Wachsmuth, Zdzislaw Pokutycki, Flavia Alman, Mario Canali, Interferenzen IV (on radio art) Liveness / Philip Auslander im digitalen Zeitalter / Uwe Jean Heuser Perform or else – from discipline to performance Videokunst in Deutschland 1963 – 1982 Arquitecturanimación / F. Massad, A.G. Yeste Ed. Bernd Schulz John Lasseter, Peter Conn, Eihachiro Nakamae, Edward Zajec, Franc Curk, Jasdan Joerges, Xavier Nicolas, TRANSIT #2 -

Marita Liulia Multimedia Artist

Marita Liulia Multimedia Artist Marita Liulia is a versatile visual artist and a pioneer of interactive multimedia. Her production includes multi-platform media art works, photography, painting, stage performances and books. Her works have been exhibited and performed in over 45 countries. Liulia studied literature and political history at the University of Helsinki and visual arts at the University of Art and Design Helsinki. In the 1990’s, she expanded her scope from theatre and the visual arts to digital and interactive media, becoming one of the pioneers of the industry. Her first digital artworks include Jackpot (1991), CD-ROM Maire (1994) and Ambitious Bitch (1996), a humorous CD-ROM about femininity. SOB (Son of a Bitch), a CD-ROM about men and masculinity, followed in 1999. In Tarot, she combined art, entertainment and technology. The work was published in six different formats and ten languages in 2000–2004. In 2001, Liulia created the works Manipulator and Animator with musician-composer Kimmo Pohjonen. HUNT, her collaboration with Tero Saarinen, premiered in 2002. Choosing My Religion, an exhibition and reference work on the world’s major religions opened in 2009 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma in Helsinki. From 2011 – 2013 Liulia was Artist in Residence at Aalto University where she directed a series of dance movies. Liulia has received numerous awards for her achievements as an artist, including the Prix Möbius International, the Prix Ars Electronica and the Finland Prize. She founded the production company Medeia in 1997 and Prix Möbius Nordica, a media culture competition in 2000. www.maritaliulia.com . -

OLA KOLEHMAINEN Born 1964 in Helsinki, Finland Lives and Works in Berlin, Germany

OLA KOLEHMAINEN Born 1964 in Helsinki, Finland Lives and works in Berlin, Germany EDUCATION 1993-99 Master of Arts in Photography, University of Art and Design Helsinki 1988-92 University of Helsinki, Department of Journalism MEMBERSHIP 1996- Union of Artist Photographers, Helsinki SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Back to Square Black, Galerie Forsblom, Helsinki 2019 Sacred Places, Mirko Mayer gallery, Cologne, Germany COELN, Cathedral of Light, Rheinishes Bildarchive as Guest in Kaune Contemporary, St. Joseph Chapel, Cologne 2018 Sacred Spaces, BGE Contemporary Art Projects, Stavanger, Norway Galerie der Moderne, Munich, Germany 2017 Sacred Spaces, Helsinki Art Museum, Helsinki Spanish Works Galería Senda, Barcelona, Spain It Never Entered My Mind, Galleri Brandstrup, Oslo, Norway Sinan Project, Borusan Contemporary, Istanbul 2015 Ola Kolehmainen, Purdy Hicks Gallery, London, UK Sense of Volume, Galerie Forsblom, Helsinki, Finland 2014 Reason & Intuition: Alvar Aalto and Ola Kolehmainen in Soane, Pitzhanger Manor House & Gallery, London Geometric Light, by Sauerbruch Hutton, Haus am Waldsee, Berlin 2012 Galleri Brandstrup, Oslo, Norway Enlightenment, Alvar Aalto Museum, Kyvaskyla, Finland 2011 Galerie Forsblom, Helsinki, Finland Gallery TAIK, Lindenstrasse, Berlin, Germany Gallery TAIK, Bergstrasse, Berlin, Germany 2010 17th Biennale of Sydney, Austrailia A Building is not a Building, KUNTSI, Museum of Modern Art, Wasa, Finland Deutsche Werkstätten, Dresden, Germany Alvar Aalto, Galeria Senda, Barcelona, Spain 2009 A Building is not a -

Choosing My Religion & Tarot

Pour se rendre au Centre Culturel de Rencontre Abbaye de Neumünster, il est recommandé d’utiliser les parkings de la ville haute. Depuis le plateau du Saint-Esprit, un ascenseur gratuit mène au quartier du Grund, à une centaine de mètres du Centre Culturel de Rencontre Abbaye de Neumünster. A la sortie de l’ascenseur, passer le petit pont, puis prendre à gauche vers l’église Saint-Jean. Choosing my religion & Tarot The Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture Frame City of Vantaa Expositions de Marita Liulia Finnish Cultural Foundation Du 7 décembre au 15 janvier 2012 Aalto University L’Ambassade de Finlande au Luxembourg et Le Centre Culturel de Rencontre Abbaye de Neumünster vous prient de leur faire l’honneur d’assister au vernissage des expositions de Marita Liulia Choosing My Religion et Tarot le mardi 6 décembre 2011 à 18h00 dans l’Agora du Centre Culturel de Rencontre Abbaye de Neumünster Choosing My Religion 28, rue Münster . L-2160 Luxembourg Choosing My Religion views the major religions ( Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Sikhism, Hin- en présence de l’artiste duism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism and Shinto ) from female point of view. The exhibition is divided into an artistic and a factual section. The artistic part focuses on the intense experiences of religions. In the factual section ( www.maritaliulia.com/cmr ) one can Merci de confirmer votre présence : compare how religions explain human being, god, life and death. Tél.: +352 / 26 20 52 1 ou E-mail : [email protected] Tarot Le Verre de l’amitié sera offert par Bernard Massard S.A. -

Marita Liulia Choosing My Religion Marita Liulia on the Trail of Religion

Marita Liulia Choosing My Religion Marita Liulia on the trail of religion Marita Liulia’s multimedia work Choosing My Religion compares the world’s major religions: Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Sikhism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism and Shinto. Liulia views religions as an artist, as a researcher, and as a woman. This integrated set of works is made up of individual artworks that draw on the stories and visual worlds of the nine religions, along with factual works that set out their founding ideas. The exhibition at Bomuldsfabriken Kunsthall incorporates photographic works, paintings, installations and religious objects. In the photographs Liulia appears in the roles of scholar and priest, not something that religions normally permit to women. The paintings reflect the influence of oriental art. Liulia’s interest in contemporary dance and technology has resulted in a video called Jumalattaren paluu (Return of the Goddess), in which Virpi Pahkinen dances in a holographic projection. There are also documentary films that take us on a journey with the artist into the process by which the works came about. The religion information pack that also forms part of the project is on the Internet at: www.maritaliulia.com/cmr. The website sets out the basic ideas of the religions and parallels their concepts of the world, the human being, god(s), life and death. The exhibition and website are accompanied by the art book Choosing My Religion published by Maahenki. In it Marita Liulia and scholar of religion Terhi Utriainen write about the place of religion in the contemporary world. The highly versatile, prize-winning media artist Marita Liulia is internationally one of Finland’s best-known contemporary artists. -

Staying Power to Finnish Cultural Exports

Ministry of Education Staying Power to Finnish Cultural Exports The Cultural Exportation Project of the Ministry of Education, the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Trade and Industry Publications of the Ministry of Education, Finland 2005:9 Hannele Koivunen Staying Power to Finnish Cultural Exports The Cultural Exportation Project of the Ministry of Education, the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Trade and Industry Publications of the Ministry of Education, Finland 2005:9 Hannele Koivunen Opetusministeriö • Kulttuuri-, liikunta- ja nuorisopolitiikan osasto • 2005 Ministry of Education • Department for Cultural, Sport and Youth Policy • 2005 Ministry of Education Department for Cultural, Sport and Youth Policy P.O. Box 29, FI-00023 Government http://www.minedu.fi http://www.minedu.fi/minedu/publications/index.html Layout: Liisa Heikkilä, Ministry of Education ISBN 952-442-886-5 (hbk.) ISSN 1458-8110 Publications of the Ministry of Education, Finland 2005:9 Abstract Meaning-intensive production and creative economy are emerging as crucial assets in international competition. Many countries revised their cultural exportation strategies in the 1990s, adopting the creative economy sector as a key strategy in international competitiveness. The strengths of Finnish cultural exports are our large creative capital, high-standard education in the creative fields, strong technological know-how, good domestic infrastructure in culture, well-functioning domestic market and high-quality creative production. Our cultural production is highly valued internationally, and we cannot meet the international demand for Finnish culture. The weak points in our cultural exports are leakage points in the value chain, information, marketing, promotion, and lack of a strategy and coordination in cultural exportation.