Does Anyone Really Know What Time It Was?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Titanic Research Project What Is It? You Will Choose a Person Involved with the Titanic from the List Provided by Your Teacher

Titanic Research Project What is it? You will choose a person involved with the Titanic from the list provided by your teacher. Steps for your research 1. You will gather information about your person by reading articles, online resources, and books. 2. You will take notes on important facts about your person and keep them in your folder. 3. You will organize your facts and sort them into like categories that will become your sections/subheadings of your expository essay. 4. You will create a thinking map and put your information into a thinking map. 5. You will write the draft of your expository essay. 6. You will revise and add transitional words, fix the any of the words in your essay. 7. You will edit your essay and check for spelling, punctuation, and capitalization. 8. You will publish your essay. If time permits you will be able to type your report. When is it due? January 6, 2017 When is the Titanic Live Museum? The week of January 9th exact times and date TBD What materials do you need? Writing folder Internet access at home or school Access to books The Titanic articles given to you by your teacher Supplies for your presentation at the Titanic Live Museum—this will vary depending on what you decide to do What is a live museum? A living museum is a museum which recreates a historical event by using props, costumes, decorations, etc. in which the visitors will feel as though they are literally visiting that particular event or person(s) in history. -

Frederick Fleet, 9 Norman Road, Freemantle: Saved

Frederick Fleet, 9 Norman Road, Freemantle: Saved Left: Frederick Fleet’s index card from the National Register of Merchant Seamen. The Register is held at the Southampton Archives Service and the image appears here with their permission. Frederick Fleet was born in Liverpool on 15 October 1887 but was abandoned by his father and mother soon after. On the 1891 census, he was aged 3 and living in the Foundling Hospital in Liverpool’s Toxteth Park. He started his career at sea in 1903 as a deck boy. Before serving on the Titanic, he had been a crew- member on her sister-ship, Oceanic, as had many of the Titanic’s crew. His address at that time was 9 Norman Road in Freemantle (see photograph below right). This was the same address on the record of his marriage to Eva Le Gros on 17 June 1917 at Freemantle parish church. He joined the Titanic in Belfast as look-out. As an able-seaman Fred earned £5 a month with an extra 5s for lookout duty. At 10 pm on the night of Sunday, 14 April 1912, he took his position in the crow’s nest with fellow look-out, Reginald Lee. Fleet spotted the iceberg near the end of his watch, just after 11.30 pm. At that time, he told the US Senate Inquiry, it appeared to be no bigger than the two tables. He rang three bells to notify the bridge an object was ahead and then called Officer Moody on the bridge to say it was an iceberg right ahead. -

Captain Arthur Rostron

CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON CARPATHIA Created by: Jonathon Wild Campaign Director – Maelstrom www.maelstromdesign.co.uk CONTENTS 1 CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………3-6 CUNARD LINE…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………7-8 CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON CONT…….….……………………………………………………………………………………………………….8-9 RMS CARPATHIA…………………………………………………….…………………………………………………………………………………….9-10 SINKING OF THE RMS TITANIC………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…11-17 CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON CONT…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….18-23 R.M.S CARPATHIA – Copyright shipwreckworld.com 2 CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON Sir Arthur Henry Rostron, KBE, RD, RND, was a seafaring officer working for the Cunard Line. Up until 1912, he was an unknown person apart from in nautical circles and was a British sailor that had served in the British Merchant Navy and the Royal Naval Reserve for many years. However, his name is now part of the grand legacy of the Titanic story. The Titanic needs no introduction, it is possibly the most known single word used that can bring up memories of the sinking of the ship for the relatives, it will reveal a story that is still known and discussed to this day. And yet, Captain Rostron had no connections with the ship, or the White Star Line before 1912. On the night of 14th/15th April 1912, because of his selfless actions, he would be best remembered as the Captain of the RMS Carpathia who rescued many hundreds of people from the sinking of the RMS Titanic, after it collided with an iceberg in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean. Image Copyright 9gag.com Rostron was born in Bolton on the 14th May 1869 in the town of Bolton. His birthplace was at Bank Cottage, Sharples to parents James and Nancy Rostron. -

Coordination Failure and the Sinking of Titanic

The Sinking of the Unsinkable Titanic: Mental Inertia and Coordination Failures Fu-Lai Tony Yu Department of Economics and Finance Hong Kong Shue Yan University Abstract This study investigates the sinking of the Titanic from the theory of human agency derived from Austrian economics, interpretation sociology and organizational theories. Unlike most arguments in organizational and management sciences, this study offers a subjectivist perspective of mental inertia to understand the Titanic disaster. Specifically, this study will argue that the fall of the Titanic was mainly due to a series of coordination and judgment failures that occurred simultaneously. Such systematic failures were manifested in the misinterpretations of the incoming events, as a result of mental inertia, by all parties concerned in the fatal accident, including lookouts, telegram officers, the Captain, lifeboat crewmen, architects, engineers, senior management people and owners of the ship. This study concludes that no matter how successful the past is, we should not take experience for granted entirely. Given the uncertain future, high alertness to potential dangers and crises will allow us to avoid iceberg mines in the sea and arrived onshore safely. Keywords: The R.M.S. Titanic; Maritime disaster; Coordination failure; Mental inertia; Judgmental error; Austrian and organizational economics 1. The Titanic Disaster So this is the ship they say is unsinkable. It is unsinkable. God himself could not sink this ship. From Butler (1998: 39) [The] Titanic… will stand as a monument and warning to human presumption. The Bishop of Winchester, Southampton, 1912 Although the sinking of the Royal Mail Steamer Titanic (thereafter as the Titanic) is not the largest loss of life in maritime history1, it is the most famous one2. -

Geographical List of Public Sculpture-1

GEOGRAPHICAL LIST OF SELECTED PERMANENTLY DISPLAYED MAJOR WORKS BY DANIEL CHESTER FRENCH ♦ The following works have been included: Publicly accessible sculpture in parks, public gardens, squares, cemeteries Sculpture that is part of a building’s architecture, or is featured on the exterior of a building, or on the accessible grounds of a building State City Specific Location Title of Work Date CALIFORNIA San Francisco Golden Gate Park, Intersection of John F. THOMAS STARR KING, bronze statue 1888-92 Kennedy and Music Concourse Drives DC Washington Gallaudet College, Kendall Green THOMAS GALLAUDET MEMORIAL; bronze 1885-89 group DC Washington President’s Park, (“The Ellipse”), Executive *FRANCIS DAVIS MILLET AND MAJOR 1912-13 Avenue and Ellipse Drive, at northwest ARCHIBALD BUTT MEMORIAL, marble junction fountain reliefs DC Washington Dupont Circle *ADMIRAL SAMUEL FRANCIS DUPONT 1917-21 MEMORIAL (SEA, WIND and SKY), marble fountain reliefs DC Washington Lincoln Memorial, Lincoln Memorial Circle *ABRAHAM LINCOLN, marble statue 1911-22 NW DC Washington President’s Park South *FIRST DIVISION MEMORIAL (VICTORY), 1921-24 bronze statue GEORGIA Atlanta Norfolk Southern Corporation Plaza, 1200 *SAMUEL SPENCER, bronze statue 1909-10 Peachtree Street NE GEORGIA Savannah Chippewa Square GOVERNOR JAMES EDWARD 1907-10 OGLETHORPE, bronze statue ILLINOIS Chicago Garfield Park Conservatory INDIAN CORN (WOMAN AND BULL), bronze 1893? group !1 State City Specific Location Title of Work Date ILLINOIS Chicago Washington Park, 51st Street and Dr. GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON, bronze 1903-04 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, equestrian replica ILLINOIS Chicago Jackson Park THE REPUBLIC, gilded bronze statue 1915-18 ILLINOIS Chicago East Erie Street Victory (First Division Memorial); bronze 1921-24 reproduction ILLINOIS Danville In front of Federal Courthouse on Vermilion DANVILLE, ILLINOIS FOUNTAIN, by Paul 1913-15 Street Manship designed by D.C. -

Titanic's Crew

TITANIC'S CREW 0. TITANIC'S CREW - Story Preface 1. TITANIC - INSIDE AND OUT 2. TITANIC'S CREW 3. MAIDEN VOYAGE 4. THE PASSENGERS 5. ICEBERGS 6. TITANIC'S WIRELESS 7. ICE WARNINGS IGNORED 8. ICEBERG RIGHT AHEAD 9. A DOOMED SHIP 10. DOOMED PASSENGERS 11. WIRELESS TRANSMISSIONS 12. RESCUE OF THE LIVING 13. RECOVERY OF THE DEAD 14. NEWSFLASH! 15. HEROES 16. A DISINTEGRATING VESSEL 17. THE REST OF THE STORY Ten teams of chain makers worked on Titanic’s anchor chains. Those chains were 3 3/8 inches in diameter. Note the cross piece on each chain link. It is called a "stud link chain." That middle bar is intended to stop the link from kinking or from deforming if it is under a heavy load. This 1911 photograph appears in Chain and Anchor Making in the Black Country, a 2006 book by Ron Moss. After she was launched on May 31, 1911 the ship was outfitted for sea duty. It took many months before those tasks were completed. She was finally ready for a sea trial on April 2, 1912. Who was in charge of Titanic? Although most of the officers were the same, the crew that managed the sea trials was different from the crew assigned to the maiden voyage. Significantly, the chief executive officer William Murdoch was replaced by the less-well-liked (but friend-of-the-captain) Henry Tingle Wilde. E.J. (Edward John) Smith was the captain. Murdoch served as 1st officer during the voyage. With the addition of Wilde to the officer staff, the crew had an extra officer on board. -

A Night to Remember Study Guide

A Night to Remember Study Guide Know these people: 1. Baker Joughin- chief baker, famous for being drunk and surviving 2. Benjamin Guggenheim- an American businessman, got dressed in best clothes for the sinking 3. Bruce Ismay- president of the White Star line, survived by jumping into a lifeboat 4. Captain Lord- captain of the Californian 5. Captain Smith- captain of the Titanic, went down with the ship 6. Charles Lightoller- 2nd officer, helped load lifeboats, after the boat sank helped keep Collapsible B afloat 7. Fifth Officer Lowe- went back to pick up survivors 8. First Officer William Murdoch- in charge when the Titanic hit the iceberg 9. omit 10. Jack Thayer Jr.- 1st class passenger, as the boat was sinking he jumped off the boat and survived 11. John Jacob Astor- richest man on board, smoke stack fell on him 12. Lookout Frederick Fleet- the lookout who saw the iceberg 13. Loraine Allison- only 1st class child to die 14. Margaret Brown- 1st class passenger, ‘Molly’, history calls her the “unsinkable” 15. Thomas Andrews- designer of the Titanic, last seen in the smoking room looking at a painting Know these questions: 16. How is Robertson’s book similar to the true story of the Titanic? Famous people, same size, both hit an iceberg and sank, names were similar, both labeled unsinkable, sank in April, not enough lifeboats, similar speeds 17. How did the people react to ice falling onto the ship from the iceberg? 3rd class passengers played with it 18. What things were lost in the cargo of the Titanic? Not the Mona Lisa :) 19. -

Saving the Survivors Transferring to Steam Passenger Ships When He Joined the White Star Line in 1880

www.BretwaldaBooks.com @Bretwaldabooks bretwaldabooks.blogspot.co.uk/ Bretwalda Books on Facebook First Published 2020 Text Copyright © Rupert Matthews 2020 Rupert Matthews asserts his moral rights to be regarded as the author of this book. All rights reserved. No reproduction of any part of this publication is permitted without the prior written permission of the publisher: Bretwalda Books Unit 8, Fir Tree Close, Epsom, Surrey KT17 3LD [email protected] www.BretwaldaBooks.com ISBN 978-1-909698-63-5 Historian Rupert Matthews is an established public speaker, school visitor, history consultant and author of non-fiction books, magazine articles and newspaper columns. His work has been translated into 28 languages (including Sioux). Looking for a speaker who will engage your audience with an amusing, interesting and informative talk? Whatever the size or make up of your audience, Rupert is an ideal speaker to make your event as memorable as possible. Rupert’s talks are lively, informative and fun. They are carefully tailored to suit audiences of all backgrounds, ages and tastes. Rupert has spoken successfully to WI, Probus, Round Table, Rotary, U3A and social groups of all kinds as well as to lecture groups, library talks and educational establishments.All talks come in standard 20 minute, 40 minute and 60 minute versions, plus questions afterwards, but most can be made to suit any time slot you have available. 3 History Talks The History of Apples : King Arthur – Myth or Reality? : The History of Buttons : The Escape of Charles II - an oak tree, a smuggling boat and more close escapes than you would believe. -

Titanic Lessons.Indd

Lee AWA Review Titanic - Lessons for Emergency Communica- tions 2012 Bartholomew Lee Author She went to a freezing North Atlantic grave a hundred years ago, April 15, 1912, hav- By Bartholomew ing slit her hull open on an iceberg she couldn’t Lee, K6VK, Fellow avoid. Her story resonates across time: loss of of the California life, criminal arrogance, heroic wireless opera- Historical Radio tors, and her band playing on a sinking deck, Society, copyright serenading the survivors, the dying and the dead 2012 (no claim to as they themselves faced their own cold wet images) but any demise. The S.S. Titanic is the ship of legend.1 reasonable use The dedication to duty of the Marconi wire- may be made of less operators, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, this note, respect- is both documented and itself legendary.2 Phil- ing its authorship lips stuck to his key even after Captain Edward and integrity, in Smith relieved him and Bride of duty as the ship furtherance of bet- sank. Phillips’ SOS and CQD signals brought the ter emergency com- rescue ships, in particular the S.S. Carpathia. munications. Phillips died of exposure in a lifeboat; Bride Plese see the survived.3 author description This note will present some of the Marconi at the end of the wireless messages of April 14. Any kind of work article, Wireless -- under stress is challenging. In particular stress its Evolution from degrades communications, even when effective Mysterious Won- communications can mean life or death. Art der to Weapon of Botterel4 once summed it up: “Stress makes you War, 1902 to 1905, stupid.” The only protection is training. -

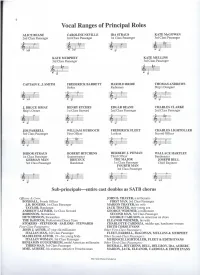

Vocal Ranges of Principal Roles

Vocal Ranges of Principal Roles ALICE BEANE CAROLINE NEVILLE IDA STRAUS KATE McGOWAN 2nd Class Passenger 2nd Class Passenger 1st Class Passenger 3rd Class Passenger KATE MURPHEY KATE MULLINS 3rd Class Passenger 3rd Class Passenger CAPTAIN E. J. SMITH FREDERICK BARRETT HAROLD BRIDE THOMAS ANDREWS Stoker Radioman Ship's Designer f J. BRUCE ISMAY HENRY ETCHES EDGAR BEANE CHARLES CLARKE Ship's Owner 1st Class Steward 2nd Class Passenger 2nd Class Passenger * li f JIM FARRELL WILLIAM MURDOCH FREDERICK FLEET CHARLES LIGHTOLLER 3rd Class Passenger First Officer Lookout Second Officer ?f f ISIDOR STRAUS ROBERT KITCHENS HERBERT J. PITMAN WALLACE HARTLEY 1st Class Passenger Quartermaster Third Officer Bandmaster GERMAN MAN BRICOUX THE MAJOR JOSEPH BELL 3rd Class Passenger Bandsman 1st Class Passenger Chief Engineer FOURTH MAN 3rd Class Passenger ^ w Sub-principals—entire cast doubles as SATB chorus Officers & Crew: JOHN B. THAYER, a millionaire BOXHALL, Fourth Officer FIRST MAN, 3rd Class Passenger J.H. ROGERS, 1st Class Passenger MARION THAYER, his wife TAYLOR, Bandsman JACK THAYER, their young son ANDREW LATIMER, 1st Class Steward GEORGE WIDENER, a millionaire ROBINSON, Stewardess SECOND MAN, 3rd Class Passenger HUTCHINSON, Stewardess GEORGE CARLSON, an American on shore THE DaMICOS, Professional Dance Team ELEANOR WIDENER, his wife STOKERS - STEVEDOR - SAILORS - STEWARDS CHARLOTTE CARDOZA, middle-age, handsome woman First-Class Passengers: EDITH CORSE EVANS JOHN J. ASTOR, 47 year old millionaire Other First-Class Passengers: ITALIAN MAN, 3rd Class Passenger FLEET, FARRELL, McGOWAN, MULLINS & MURPHEY MADELEINE ASTOR, 19—his young bride Other Second-Class Passengers: ITALIAN WOMAN, 3rd Class Passenger MURDOCH, LIGHTOLLER, FLEET & EDITH EVANS BENJAMIN GUGGENHEIM, model American millionaire Other Third-Class Passengers: THIRD MAN, 3rd Class Passenger BOXHALL, KITCHENS, BELL, BELLBOY, IDA, AUBERT, MME. -

RMS Titanic - Wikipedia

RMS Titanic - Wikipedia http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/RMS_Titanic RMS Titanic Da Wikipedia, l'enciclopedia libera. « Nemmeno Dio potrebbe fare affondare questa RMS Titanic nave. » (Il marinaio A.Bardetta del Titanic alla signora Caldwell, il 10 aprile 1912.) Il RMS Titanic era una nave passeggeri britannica della Olympic Class , divenuta famosa per la collisione con un iceberg nella notte tra il 14 e il 15 aprile 1912, e il conseguente drammatico affondamento avvenuto nelle prime ore del giorno successivo. Secondo di un trio di transatlantici, il Titanic , con le sue Descrizione generale due navi gemelle Olympic e Britannic , era stato progettato per offrire un collegamento settimanale con l'America, e Tipo Transatlantico garantire il dominio delle rotte oceaniche alla White Star Classe Olympic Line. Costruttori Harland and Wolff Cantiere Belfast, Irlanda del Nord. Costruito presso i cantieri Harland and Wolff di Belfast, il Titanic rappresentava la massima espressione della Impostazione 31 marzo 1909 tecnologia navale, ed era il più grande, veloce e lussuoso Completamento 31 marzo 1912 Entrata in transatlantico del mondo. Durante il suo viaggio inaugurale 10 aprile 1912 (da Southampton a New York, via Cherbourg e servizio Queenstown), entrò in collisione con un iceberg alle 23:40 Proprietario White Star Line, (ora della nave) di domenica 14 aprile 1912. L’impatto Amministratore Delegato: (Joseph Bruce Ismay) provocò l'apertura di alcune falle lungo la fiancata destra Destino finale Naufragato il 15 aprile 1912. del transatlantico, che affondò due ore e 40 minuti più tardi (alle 2:20 del 15 aprile) spezzandosi in due tronconi. Caratteristiche generali Dislocamento 52.310 t Nella sciagura, una delle più grandi tragedie nella storia Stazza lorda 46.328 t della navigazione civile, persero la vita 1517 dei 2227 Lunghezza 269 m passeggeri imbarcati. -

Projektarbeit Die Versunkene R.M.S. Titanic

Realschulabschlussprüfung 2013 Projektarbeit Thema Die versunkene R.M.S. Titanic Pauline Martensen und Laura Herrig Pellworm, 25. November 2012 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1.Einleitung (Pauline & Laura) 1 2.Hauptteil 2.1. Die White Star Line (Pauline) 2 2.2. Die Idee des Baues der Titanic und deren Umsetzung (Pauline) 3-4 2.3. Darstellung der drei verschiedenen Klassen (Pauline) 4-6 2.3.1. Strenge Trennung 2.3.2. Unglaublicher Luxus 2.3.3. Nach dem Vorbild Frankreichs 2.3.4. Die Ausstattung der 1. Klassen 2.3.5. Erstklassige 2. Klasse 2.3.6. Auch die 3. Klasse kann sich sehen lassen 2.4. Die wichtigsten Daten der R.M.S. Titanic (Laura) 7 2.5. Die Schwesternschiffe der Titanic (Laura) 8-9 2.5.1. Die R.M.S. (Royal Main Ship) Olympic 2.5.2. Wichtige Daten der R.M.S. Olympic 2.5.3. Die H.M.H.S (His Majesty´s Hospital Ship) Britannic 2.5.4. Wichtige Daten der H.M.H.S. Britannic 2.6. Thomas Andrews (Laura) 10 2.7. Die Route (Laura) 11 2.8. Der Kapitän: Edward John Smith (Pauline) 12 2.8.1. Die letzte Reise vor seinem Ruhestand 2.8.2. Edward J. Smith und die Passagiere der 1. Klasse 2.8.3. Die letzte Tat des Kapitäns 2.9. Die wichtigsten Passagiere an Bord (Laura) 13-14 2.9.1. Die letzte Überlebende der Titanic 2.9.2. Die vier reichsten Passagiere an Bord 2.10. Von der Kollision bis zum Untergang der Titanic (Laura) 15-18 2.11.