Annual Report of the Special Rapporteur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

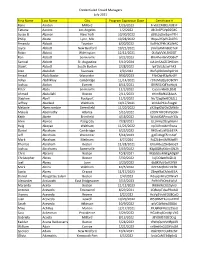

Credentialed Crowd Managers July 2021 First Name Last

Credentialed Crowd Managers July 2021 First Name Last Name City Program Expiration Date Certificate # Rano Aarden Milford 1/26/2023 FrvbECM3ELNUErF Tatiana Aarons Los Angeles 1/2/2022 J8r2x6PSVpDZGKC Susan B. Abanor New York 10/30/2022 s8lELzyDw2qmPTH Philip Abate Lynn, MA 10/28/2022 WqaslYQvPLZk07G Amanda Abbott Taunton 6/20/2022 Ka9Hs2Pkh1KUNAC Joyce Abbott New Bedford 10/21/2021 zVHllaFMm8dCTeK Robin Abbott Wilmington 12/12/2021 0fz5pVVXLSI60OT Ron Abbott Somerville 9/22/2023 8hk4henBxVDbBv7 Samuel Abbott St. Augustine 5/10/2024 xiA1mSAdZE0HG4m Stuart Abbott South Boston 2/28/2022 lpY1blLJbzwFhK3 Alan Abdallah Swansea 2/9/2022 WxFq0DJ9mPqGHof Amaal Abdelkader Worcester 9/30/2023 FYtrOqHF3pfkzOY Adiya Abdilkhay Cambridge 11/14/2021 r97oMqQly3OBcNY Joshua Abdon Everett 8/11/2021 8VW51lQEYwhliyk Peter Abdu Somerville 11/2/2022 Cuaserkl6OLDbIZ Ahmed Abdullahi Boston 2/11/2023 tHImRAfKLS8JsxA Stephen Abell Rockport 11/5/2023 NoT2agXeKIOBZL1 Jeffrey Abellard Waltham 10/17/2021 eCG3eP61sFxog9l Melanie Abercrombie Greenfield 11/20/2022 aY2bpJ0WOsCMN0v Makyla Abernathy Atlanta 5/15/2022 cODN7RFDYaYpDcH Keith Abete Brimfield 4/18/2022 Wxh4f0APmovh33s Alvin Abinas Pasig City 7/28/2021 ULzHHuZOsydr6mI Haig Aboyan Waltham 11/26/2022 np3UfnoLfzH5wca Daniel Abraham Cambridge 6/25/2022 9HDvxEuWGiLiE7A Jeff Abraham Worcester 5/14/2023 gj0TzUxgE5rmA9F Mark Abraham Methuen 4/7/2024 FxZZL4mXMf6JwRY Thomas Abraham Reston 11/28/2021 EVLm0eLZSHSmsq9 Joshua Abrahams Somerville 5/19/2022 Kdp8QRqKtAmGN2h Chris Abrams Boston 10/8/2021 MSbGbeMkEgADg9P Christopher -

Soccernews Issue # 07, July 10Th 2014

SoccerNews Issue # 07, July 10th 2014 Continental/Division Tires Alexander Bahlmann Phone: +49 511 938 2615 Head of Media & Public Relations PLT E-Mail: [email protected] Buettnerstraße 25 | 30165 Hannover www.contisoccerworld.de SoccerNews # 07/2014 2 World Cup insight German team watched the match at their base camp in South Bahia, where they had been celebrated by the locals upon their return. (Video-Link Süddeutsche Zeitung: Final countdown http://www.sueddeutsche.de/sport/herzlicher- empfang-trotz-1.2037941). The 23 players and is running for the the coaching staff headed by Joachim Loew watched how two-time World Cup champions Argentina positively toiled to reach the final. DFB team The match in no way reached the level of the semi-final in Belo Horizonte on the previous After the magical night with the historic 7-1 evening, acclaimed around the globe, when triumph over Brazil, Argentina is the last ob- the German national team achieved a sen- stacle on the road to the fourth World Cup sational, unique triumph over the World Cup title for the German national team. In the hosts. Brazil and the Netherlands will meet in disappointingly colourless second semi-final the “small final” for third place in the capital of the 2014 FIFA World Cup™, the Argentinians Brasilia (22:00hrs CSET), a fixture won by The national team and captain Philipp Lahm after the historic triumph against Brazil defeated the Netherlands 4-2 in a penalty the DFB team in 2006 (against Portugal) and shoot-out after 120 goalless minutes in Sao 2010 (against Uruguay). -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

Populism in Latin America

Populism in Latin America Oxford Handbooks Online Populism in Latin America Carlos de la Torre The Oxford Handbook of Populism Edited by Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy Print Publication Date: Oct 2017 Subject: Political Science, Political Behavior, Comparative Politics Online Publication Date: Nov 2017 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198803560.013.8 Abstract and Keywords Since the 1930s and 1940s until the present, populist leaders have dominated Latin America’s political landscapes. This chapter explains the commonalities and differences between the different subtypes of Latin American populism—classical, neoliberal, and radical. It examines why these different manifestations of populism emerged, and their democratizing and inclusionary promises while seeking power. Then it analyzes their impact on democracy after gaining office. Whereas populists seeking power promise to include the excluded, once in power populists attacked the institutions of liberal democracy, grabbed power, aimed to control social movements and civil society, and clashed with the privately owned media. Keywords: Latin America, classical populism, neoliberal populism, radical populism, democracy, authoritarianism LATIN America is the land of populism.1 From the 1930s and 1940s until the present, populist leaders have dominated the region’s political landscapes. Mass politics emerged with populist challenges to the rule of elites who used fraud to remain in power. The struggle for free and open elections, and for the incorporation of those excluded from politics, is associated with the names of the leaders of the first wave of populism: Juan and Eva Perón in Argentina, Getulio Vargas in Brazil, Victor Raúl Haya de la Torre in Perú, or José María Velasco Ibarra in Ecuador. -

Monarcas, Bufones, Políticos Y Audiencias Comparación De La Sátira Televisiva En Reino Unido Y España, Revista Latina De Comu

Valhondo Crego, J. L. (2011): Monarcas, bufones, políticos y audiencias Comparación de la sátira televisiva en Reino Unido y España, Revista Latina de Comu... Investigación | Forma de citar/how to cite | informe de revisores/referees | agenda | metadatos | formato para imprimir | PDF dinámico | Creative Commons DOI: 10.4185/RLCS-66-2011-932-252-273 | ISSN 1138-5820 | RLCS # 66 | 2011 | | Monarcas, bufones, políticos y audiencias. Comparación de la sátira televisiva en Reino Unido y España Monarchy, jesters, politicians and audiences. Comparison of TV satire in UK and Spain Dr. José-Luis Valhondo-Crego [C.V.] Doctor por la Universidad Rey Juan Carlos de Madrid - [email protected] Resumen: Los programas de sátira se han convertido en una forma de comunicación política frecuente en la televisión. Tras la liberalización de los medios y la globalización de los formatos, países como España han adoptado formatos satíricos procedentes de otros que, como Reino Unido, contaban con una tradición que se remontaba casi al inicio de la televisión. El objetivo de este artículo es el de pergeñar una definición del género teniendo en cuenta los ejemplos de los dos países mencionados y, también, refiriéndonos a dos épocas separadas por el fenómeno de la liberalización de la televisión. Aplicaremos para ello una metodología comparativa respecto al perfil de las audiencias, de los bufones de la sátira y del papel jugado por la clase política a lo largo de la corta historia de la sátira en televisión. Los resultados señalan una evolución. En los años sesenta del siglo XX, el género apuntaba a las clases medias, sus autores pretendían popularizar la política para una sociedad muy respetuosa con el establishment y los políticos censuraron el espacio en previsión de que pudiera desequilibrar ideológicamente los procesos electorales. -

Middleton Powers Bucks Past Hawks

ARAB TIMES, TUESDAY, JUNE 29, 2021 16 Spain’s Cesar Azpilicueta, (right), scored against Croatia during the Euro 2020 soccer championship round of 16 match between Croatia and Spain, at Parken stadium in Copenhagen, Denmark. (AP) Sports Latest sports scores at — http://sports.arabtimesonline.com Hazard scores winning goal as top-ranked team reach quarters Belgium keep Ronaldo in check, end Portugal title defense SEVILLE, Spain, June 28, (AP): Bel- gium stopped Cristiano Ronaldo on one end, and had just enough attacking power on the other. The top-ranked Belgians held Ron- aldo scoreless and held onto a fi rst-half lead to beat Portugal 1-0 and advance to the quarterfi nals of the European Championship. Ronaldo, who threw his captain’s armband to the ground in de- spair after the fi nal whistle, is still one goal shy of becom- ing the all- time men’s top scorer in inter- national soccer. He came into the match tied Hazard with former Iran striker Ali Daei at 109 goals. Belgium, which have never before won a major soccer title, will next face Italy on Friday in Munich. Belgium’s potent attack, led by Kevin De Bruyne, Eden Hazard and Romelu Lukaku, also struggled, but Thorgan Hazard scored the winning goal in the 42nd minute with a swerv- ing shot from outside the area. Portu- gal goalkeeper Rui Patrício was left wrong-footed and was late to swat the ball away. Belgium played most of the second half without De Bruyne, who had to be substituted after being tackled from Belgium’s Thomas Vermaelen, (left), and Portugal’s Cristiano Ronaldo challenge for the ball during the Euro 2020 soccer championship round of 16 match between Belgium and Portugal at the behind and injuring his left ankle. -

Zizinho Seri Convidado Pelo Ferroviário

*****•» — : 99 ._»' :hada i tapam Reiicâo ¦ plfIHBUifPH ¦¦•¦li" j IjensaaoitaE Jn3 I W\m Bju |. Cariocas Da Guia único punido — Deia- lhes dá reunião ¦"-' flenrique marcou o _lheiro do órgão goal isolado, dentro judicia- — •:« *> aparf^tlSrias íoi conse- rio m 8.a r$a partida Renda ¦Wda* *3ÍC* Mte pelo futebol bra- . (Texto de e *'&%(^ida esta único "punido, Cr$2U48.315,00 do o <Sremiõ Porto-Ba. Guia, Jogador ^^gjjte reunião de ontem. Pegou 3 ____,ueiro> de grande púloa outros detalhes • e(luipe d° B°Capartidas página) «íègrenS^eou l £ ~ vèj. PAULO —• (Serv. Esp. do Pa- DSc0i"°toWI'' raná Esportivo) — 25 — O seleciona- fll ' ^Sr**"^TM**^' r 'L'l^*.*-Í**-^***'***'*"'' *^* lt 9 d© fiaulista de íutebol nâo conseguiu a; reabilitação, dentro da série que realizou com o scratch, caindo des- tá jfeita pela contagem minima. em nieno Pacaembu • A peleja não conseguiu o mesmo no ulti- aspecto do cotejo realizado ' mi*»,domingo, destacando-se apenai pela extrema violência que os Joga- Continua na 6.a pg. ""*•**A ,condição de artilheiro¦'¦''¦¦ ª-'¦ <¦¦ 榦 w ¦ - - " ' ••...:¦«>' ' '"**m*'k^^^z-Tr _u j34__\\ •\,Z. -^*v$Si_wmy_£&^íi3m\jmZ- ***.'*'"'***¦'* i b ^Val0W ação esta tarde, no gramado de Nelson Medrado l i ataque Riobran.uist,. que estarão em \\ do m m i m m m ¦ -m-wm-* JJ ' '--¦¦¦¦ "—-«l vvw^wwmmmmirv* m mm ,I ¦ ¦ Treina-r.,„.i>Tn»" ' 0 Rio Branco mmgr — — ²Capitalmi-^ I ParaBu í w v__m prJoaar 3 Wa w *** -—.Na ga - ^^^« i Postei a presença ie Morretes no cotetiwoeMe-En- | t. com ansiosidade^1 saio aguardado ser assistido Dor dofcAgua Agua horas.horas, Ipromete - : - . -

Recepción Televisiva Y Adolescentes. El Programa "Caiga Quien Caiga" Producido En Argentina Y Las Prácticas Políticas De Los Adolescentes

Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 6 – junio de 1998 Edita: Laboratorio de Tecnologías de la Información y Nuevos Análisis de Comunicación Social Depósito Legal: TF-135-98 / ISSN: 1138-5820 Año 1º – Director: Dr. José Manuel de Pablos Coello, catedrático de Periodismo Facultad de Ciencias de la Información: Pirámide del Campus de Guajara - Universidad de La Laguna 38200 La Laguna (Tenerife, Canarias; España) Teléfonos: (34) 922 31 72 31 / 41 - Fax: (34) 922 31 72 54 Recepción televisiva y adolescentes. El programa "Caiga quien caiga" producido en Argentina y las prácticas políticas de los adolescentes Dra. Paulina Beatriz Emanuelli © Escuela de Ciencias de la Información - Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias Sociales - Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (Argentina) [email protected] De la concepción política a la recepción y las prácticas políticas La problemática de los medios masivos de comunicación social y las nuevas tecnologías han ido ocupando un papel relevante en la reproducción y crecimiento de la sociedad actual. El vertiginoso desarrollo de los medios masivos (prensa, radio, televisión etc.) desde finales de la segunda guerra mundial y la importante adopción de nuevas tecnologías en la última década marcan sin dudas la oferta y el consumo de medios en nuestra sociedad. Las grandes transformaciones en las áreas de producción, en los formatos y hasta en los géneros que se entremezclan y funden, establecen nuevas relaciones con los públicos y los procesos políticos que vive nuestro país. En este nuevo paisaje massmediático, que trasciende las fronteras geográficas, se diseñan nuevos mapas de consumo y recepción. En ellos se definen viejas y nuevas relaciones, marcos y reglas para la interacción entre los sujetos, sus identidades y socialización, y sus sistemas de normas y valores. -

La Verdadera Historia De Los Hermanos Marx Contiene Escenas Inéditas De Su Vida Privada, Pero También Su Inimaginable Participación En Varios De Los

L A V E R D A D E R A HISTORIA DE LOS HERMANOS MARX D E JU LI O S A LV AT IE R R A dossier de producción teatro meridional s.L. L A V ER D AD E RA HISTORIA DE LOS HERMANOS MARX Presentación ¿Es este mundo absurdo? ¿Y aquél ? ¿Es verdadera la historia que conocemos? ¿O la verdad es que la verda - dera historia es mentira? ¿Sería hora de contar real - mente cómo fueron las cosas, caiga quien caiga, o será mejor reconocer que no tenemos ni idea? ¿Quiénes somos? ¿A dónde vamos? Y, sobre todo, ¿de dónde ve - nimos, que traemos tan manchados los pantalones? A todas estas preguntas, y a otras incluso más serias, in - tenta responder este espectáculo construido a partir del universo humorístico, vital, cinematográfico y literario de Groucho y su familia. No es, a pesar de que pudiera pa - recerlo, un espectáculo del absurdo, si no un intento de reflexionar -con mucho humor, desde luego- sobre nues - tro mundo aprovechando esa materia densa y maravi - llosa que es el universo marxiano , especialmente el de Groucho, pero también el de sus hermanos . En todo el material que esta familia dejó tras su paso por este mundo -en sus películas, en sus espectáculos, en sus biografías y en sus escritos- hay substancia para va - rias obras de teatro. Comedias, dramas, obras de época e incluso podríamos imaginar alguna tragedia, aunque nosotros no pretendemos, desde luego, rizar el rizo ni ex - traer sombras de quien quiso, sobre todo, sembrar luces. En uno de sus escritos, Groucho dice: calculo que no existen ni un centenar de comediantes de primera fila, hombres o mujeres, en todo el mundo. -

Diplomatic List – Fall 2018

United States Department of State Diplomatic List Fall 2018 Preface This publication contains the names of the members of the diplomatic staffs of all bilateral missions and delegations (herein after “missions”) and their spouses. Members of the diplomatic staff are the members of the staff of the mission having diplomatic rank. These persons, with the exception of those identified by asterisks, enjoy full immunity under provisions of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Pertinent provisions of the Convention include the following: Article 29 The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom, or dignity. Article 31 A diplomatic agent shall enjoy immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving State. He shall also enjoy immunity from its civil and administrative jurisdiction, except in the case of: (a) a real action relating to private immovable property situated in the territory of the receiving State, unless he holds it on behalf of the sending State for the purposes of the mission; (b) an action relating to succession in which the diplomatic agent is involved as an executor, administrator, heir or legatee as a private person and not on behalf of the sending State; (c) an action relating to any professional or commercial activity exercised by the diplomatic agent in the receiving State outside of his official functions. -- A diplomatic agent’s family members are entitled to the same immunities unless they are United States Nationals. -

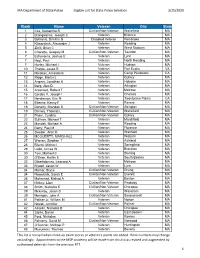

Eligible List for State Police Selection 3/25/2020

MA Department of State Police Eligible List for State Police Selection 3/25/2020 Rank Name Veteran City State 1 Cila, Samantha R Civilian/Non-Veteran Wakefield MA 2 Brangwynne, Joseph C Veteran Billerica MA 3 Bethanis, Dimitris G Disabled Veteran Pembroke MA 4 Klimarchuk, Alexander J Veteran Reading MA 5 Ziniti, Brian C Veteran West Roxbury MA 6 Charette, Gregory M Civilian/Non-Veteran Taunton MA 7 Echevarria, Joshua E Veteran Lynn MA 7 Hoyt, Paul Veteran North Reading MA 7 Hurley, Michael J Veteran Hudson MA 10 Tharpe, Jesse R Veteran Fort Eustis VA 11 Harakas, Amanda K Veteran Camp Pendleton CA 12 Ridge, Martin L Veteran Quincy MA 13 Angers, Jonathan A Veteran Holyoke MA 14 Berg, Alex D Veteran Arlington MA 15 Arsenault, Robert T Veteran Melrose MA 16 Cordes V, Joseph I Veteran Chelsea MA 17 Henderson, Eric N Veteran Twentynine Palms CA 18 Etienne, Kenny F Veteran Revere MA 19 Doherty, Brandon S Civilian/Non-Veteran Abington MA 19 Dorney, Thomas L Civilian/Non-Veteran Wakefield MA 21 Pham, Cynthia Civilian/Non-Veteran Quincy MA 22 Sullivan, Michael T Veteran Marshfield MA 23 Mandell, Michael A Veteran Reading MA 24 Barry, Paul M Veteran Florence MA 25 Sweder, Aron D Veteran Waltham MA 25 MCGUERTY, MARSHALL Veteran Woburn MA 27 Warren, Stephen T Veteran Ashland MA 28 Rivest, Michael Veteran Springfield MA 29 Ladd, James W Veteran Brockton MA 30 Tosi, Michael C Veteran Sterling MA 30 O'Brien, Kaitlin E Veteran South Boston MA 32 Dibartolomeo, Leonard A Veteran Melrose MA 33 Blydell, Jason W Veteran Lynn MA 34 Molnar, Bryce Civilian/Non-Veteran -

EC-XIX & Cop-XI June 29 – July 2, 2004 Buenos Aires, Argentina

INTER-AMERICAN INSTITUTE FOR GLOBAL CHANGE RESEARCH EC-XIX & CoP-XI June 29 – July 2, 2004 Buenos Aires, Argentina 7_ECXIX/CoPXI/DID/07 June 2004 EC - COP MEETING – BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA. COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH NETWORK-CRN STATUS EC - COP MEETING – BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA. COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH NETWORK-CRN STATUS. EDUARDO M. BANUS 1 6/7/2004 4:29 PM EC / COP MEETING – BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA. COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH NETWORK – CRN STATUS INDEX 1. CRN PROJECT SUMMARIES 2. CRN ADDITIONAL OR PARALLEL FUNDS • TABLE • BY CRN´S • BY ORGANIZATIONS: TABLE • BY ORGANIZATIONS: GRAPHIC • BY COUNTRY / INSTITUTIONS - GRAPHICS • BY CRN 3. CRN STUDENTS STATUS: TABLE • BY LEVEL - GRAPHIC • BY COUNTRY - GRAPHIC • BY UNIVERSITIES - GRAPHIC 4. CRN PUBLICATIONS ISSUED: TABLE • BY CRN´S - GRAPHICS • TOTAL NUMBER BY YEAR/CRN - GRAPHIC • TOTAL NUMBER YEAR 1999 - GRAPHIC • TOTAL NUMBER YEAR 2000 - GRAPHIC • TOTAL NUMBER YEAR 2001 - GRAPHIC • TOTAL NUMBER YEAR 2002 - GRAPHIC • TOTAL NUMBER YEAR 2003 - GRAPHIC 5. CRN INSTITUTIONS & SCIENTISTS: TABLE • CRN INSTITUTIONS BY COUNTRY - GRAPHIC • CRN ORIGINALS Vs. ACTUAL COUNTRIES EC - COP MEETING – BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA. COLLABORATIVE R ESEARCH NETWORK-CRN STATUS. EDUARDO M. BANUS 2 6/7/2004 4:29 PM EC - COP MEETING – BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA. COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH NETWORK-CRN STATUS. EDUARDO M. BANUS 3 6/7/2004 4:29 PM INTRODUCTION This document summarizes all the data derived from a survey undertaken in the IAI CRN projects in the following topics: 1. Additional/Parallel funds 2. Students 3. Publications 4. Scientists and/or Institutions The results obtained under these four topics clearly show that the CRN program has contributed to the establishment of a network of institutions, scientists, students, and financial resources.