Late 19^0'S When Atlanta Was Strictly Segregated, and Non-Indigent While

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negroes Are Different in Dixie: the Press, Perception, and Negro League Baseball in the Jim Crow South, 1932 by Thomas Aiello Research Essay ______

NEGROES ARE DIFFERENT IN DIXIE: THE PRESS, PERCEPTION, AND NEGRO LEAGUE BASEBALL IN THE JIM CROW SOUTH, 1932 BY THOMAS AIELLO RESEARCH ESSAY ______________________________________________ “Only in a Negro newspaper can a complete coverage of ALL news effecting or involving Negroes be found,” argued a Southern Newspaper Syndicate advertisement. “The good that Negroes do is published in addition to the bad, for only by printing everything fit to read can a correct impression of the Negroes in any community be found.”1 Another argued that, “When it comes to Negro newspapers you can’t measure Birmingham or Atlanta or Memphis Negroes by a New York or Chicago Negro yardstick.” In a brief section titled “Negroes Are Different in Dixie,” the Syndicate’s evaluation of the Southern and Northern black newspaper readers was telling: Northern Negroes may ordain it indecent to read a Negro newspaper more than once a week—but the Southern Negro is more consolidated. Necessity has occasioned this condition. Most Southern white newspapers exclude Negro items except where they are infamous or of a marked ridiculous trend… While his northern brother is busily engaged in ‘getting white’ and ruining racial consciousness, the Southerner has become more closely knit.2 The advertisement was designed to announce and justify the Atlanta World’s reformulation as the Atlanta Daily World, making it the first African-American daily. This fact alone probably explains the advertisement’s “indecent” comment, but its “necessity” argument seems far more legitimate.3 For example, the 1932 Monroe Morning World, a white daily from Monroe, Louisiana, provided coverage of the black community related almost entirely to crime and church meetings. -

FOR SALE! Studio Closing! Atlanta Based

For Back-to-School Fashion NNPA: Proactive and Profitable and Savings .. * The National Newspaper Publisher Association members Christopher Bennett, Seattle Cleretta (NNPA), the Black Press of held its 51st Medium; JEROMES America, Annual Thomas-Blackmon, Mobile Beacon; Andrew The convention in Atlanta in June. With the theme: Proactive and Cooler, City Profitable* the NNPA Sun; Frances Murphy Draper, Afro American Newspaper Your Accounts Welcomed 1991 attendance doubled. Conferees enjoyed Group; William Garth, Chicago Citizen Carlton dynamic speakers such as Operation PUSH President Rev. B. Goodie Newspapers; C4A kl I IOCDTV #CURTAINS .READY-TO-'READY-TO. .BEDSPREADS -JOO 7A1A Williamson Sr., Rev. Henry 1, Reporter Publications; John Holoman, Herald DaIN. LIDCnlT .draperies wear .slipcovers Bernice King,' Essencc Magazine Editor-in- Dispatch; Dr. Ruth Love, California Voice; James Washington, Chief Susan . » Taylor, Congressman William Cray and Second Dallas ^Weekly; and Melyvn Williams, Macon* Courier. :1» i.m. lo S30 p.m. Morwtay-Satuiday Pond Wtdnsadsys Episcopal District (AME) Bishop Hamct Brookins, Thought Sponsors for the 1991 NNPA June Convention included: ¦ provoking workshops were led by National Bar Association Kraft General Foods, Philip Morris Tobacco Co., Miller President Algentia Scott founder of the ' for a Brewing - New Davis,, Organization Co., Southland Corporation, American Tobacco Co., Ford Motor Co., Equality Rev. Charles Stith, Money Watch TV host Theodore Martell Cognac, Pepsi-Cola Co., Shoney's, Coca Cola USA, Daniels, and: * ys Census specialist Dwight Johnson. McDonald's Corp., Coors Brewing Co., R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., rtawt mluih, Elections were held and the following publishers are. the General Motors Schieffelin & new NNPA Co., Somerset Co. -

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

RTM 360 | Michigan Chronicle | 2019 Media Kit CONTENTS Page No

RTM 360 | Michigan Chronicle | 2019 Media Kit CONTENTS Page No ABOUT US 3 - 4 OUR AUDIENCE 5 - 6 PRODUCTS AND SERVICES 7 - 15 • PRINT 8 • TARGETED BANNER & VIDEO MARKETING 9 • EMAIL MARKETING 10 • TARGETED EMAIL 11 • E-NEWS DAILY 12 • NATIONAL SWEEPSTAKES AND CONTESTS 13 • SOCIAL MEDIA 14 • BRANDED PROJECTS 15 • BRANDED EVENTS 16 • RTM360 17 EDITORIAL AND EVENTS CALENDAR 18 – 20 • QUARTERS 1 & 2 19 • QUARTERS 3 & 4 20 RATES & SPECIFICATIONS 21 – 27 • CIRCULATION 22 • DISPLAY RATES 23 • DIGITAL & PACKAGES 24 • CLASSIFIED RATES 25 • INSERT RATES 26 • AD SPECS 27 RTM 360 | Michigan Chronicle | 2019 Media Kit Media Kit| 21 -- 2 A B O U T U S Real Times Media (RTM) is a Detroit-based multimedia company with a legacy that stretches back over 100 years. As the parent company to five of the country’s most respected African American-owned news organizations, the Atlanta Daily World, Atlanta Tribune: The Magazine, the Chicago Defender, the Michigan Chronicle, and the New Pittsburgh Courier, it is our job to maintain the heartbeat of the African American voice. Being built on the foundation of historic brands affords RTM a depth of knowledge and assets that are multi-generational, relevant, and trustworthy. RTM has an ongoing commitment to delivering quality news, events, and entertainment for African American audiences. In addition to its news brands, RTM offers custom programming and niche publishing through Who’s Who In Black—a professional lifestyle brand focused on live and virtual business/social events and content; strategic communications consultancy services through its marketing services arm, RTM360°, and RTM Digital Studios, an unparalleled archive of historical photographs, videos, and film clips of the African American experience available through licensing for advertising, marketing, publishing, and film initiatives. -

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Guide to the educational resources available on the GHS website Theme driven guide to: Online exhibits Biographical Materials Primary sources Classroom activities Today in Georgia History Episodes New Georgia Encyclopedia Articles Archival Collections Historical Markers Updated: July 2014 Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Table of Contents Pre-Colonial Native American Cultures 1 Early European Exploration 2-3 Colonial Establishing the Colony 3-4 Trustee Georgia 5-6 Royal Georgia 7-8 Revolutionary Georgia and the American Revolution 8-10 Early Republic 10-12 Expansion and Conflict in Georgia Creek and Cherokee Removal 12-13 Technology, Agriculture, & Expansion of Slavery 14-15 Civil War, Reconstruction, and the New South Secession 15-16 Civil War 17-19 Reconstruction 19-21 New South 21-23 Rise of Modern Georgia Great Depression and the New Deal 23-24 Culture, Society, and Politics 25-26 Global Conflict World War One 26-27 World War Two 27-28 Modern Georgia Modern Civil Rights Movement 28-30 Post-World War Two Georgia 31-32 Georgia Since 1970 33-34 Pre-Colonial Chapter by Chapter Primary Sources Chapter 2 The First Peoples of Georgia Pages from the rare book Etowah Papers: Exploration of the Etowah site in Georgia. Includes images of the site and artifacts found at the site. Native American Cultures Opening America’s Archives Primary Sources Set 1 (Early Georgia) SS8H1— The development of Native American cultures and the impact of European exploration and settlement on the Native American cultures in Georgia. Illustration based on French descriptions of Florida Na- tive Americans. -

Finding and Using African American Newspapers

Finding and Using African American Newspapers Timothy N. Pinnick [email protected] http://blackcoalminerheritage.net/ INTRODUCTION African American researchers will find black newspapers an extremely valuable part of their search strategy. Although mainstream newspapers should always be consulted, African American newspapers will provide nuggets of information that can be found nowhere else. Although the first African American newspaper was established in 1827, it is in the post Civil War period that the black press experienced tremendous growth. Hundreds of newspapers appeared to quench the thirst for knowledge in the newly freed slaves, and to provide an accurate and positive image of the race. Clint C. Wilson took the incomplete manuscript of the foremost historian of the African American press, Armistead Pride and produced A History of the Black Press in 1997. It is a great source of information on black newspapers. Another worthwhile source can be found online at the public television website of PBS. They produced the documentary film, “The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords” in 1999, and their website is rich in reference material. http://www.pbs.org/blackpress/index.html VALUE OF BLACK NEWSPAPERS Aside from the most obvious benefit of locating obituaries, researchers can discover: an exact or nearly exact event date (birth, death, or marriage) of an ancestor, therefore enhancing the odds of a successful outcome when the eventual request for the vital record is made. Remember, some places will only search a short span of years in their index, and charge you whether they find the record or not. additional information on the event that will not be found on the vital record. -

Caught in the Cross Fire : African Americans and Florida's System of Labor During World War II

University of South Florida Digital Commons @ University of South Florida USF St. Petersburg campus Faculty Publications USF Faculty Publications 2012 Caught in the Cross Fire : African Americans and Florida's System of Labor during World War II James Anthony Schnur Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/fac_publications Recommended Citation Schnur, James A. "Caught in the Cross Fire: African Americans and Florida's System of Labor during World War II." Sunland Tribune: Journal of the Tampa Historical Society 19 (November 1993): 47-52. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the USF Faculty Publications at Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. It has been accepted for inclusion in USF St. Petersburg campus Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAUGHT IN THE CROSS FIRE: AFRICAN AMERICANS AND FLORIDA’S SYSTEM OF LABOR DURING WORLD WAR II By JAMES A. SCHNUR The Second World War greatly altered promising them "complete franchise, Florida's social climate. The trends of freedom, and political and social equality." tourism, business progressivism, ur- Guards closely monitored activities in the banization, and industrial development that Scrub and other black areas of the Cigar evolved during the war and flourished in its City. In June 1918, the mayor of Miami aftermath competed with conventional ordered police to prohibit any gathering of agricultural and extractive enterprises. blacks in Colored Town because he feared Countless soldiers served on Florida's such an assembly might become rowdy and military bases, and many returned after the unmanageable. -

The Atlanta Constitution Circulation

CIRCULATION CIRCULATION LA*T »imi>AT. 47,885 THE ATLANTA CONSTITUTION 49,425 Omar mm* Smmtmf. carrier tttl-nrr, U orata Vol. XLVUJ. — No. 158. ATLANTA. QA., SATUBDAY MORNING, NOVEMBER 20, 1915.—FOURTEEN PAGES. MBKl* c*»i«» «• the atrMta and at »ew« •(•Mete fi e*Bt»> Ca/f'forn/afis and Af/anfans Georgia Woman Is Declared SERBS BEATEN TO PIECES Gossip Over the Telephone Best Farmer in the Southeast At Opening of New Service BY CORONER'S JURY BETWEEN BULGAR HAMMER Across the desert, over the Kockle IN LETTING BABE DIE ANB THE TEUTONIC ANVIL and through western plains last nigh there came contributions to the enter- HARVEST FESTIVAL tainment presented by the Southern Six Physicians, After Hear- Bell Telephone and Telegraph company to 250 city and state officials and busi ness men at the chamber of commerce ing Evidence, Hold Dr. Almost Trapped, the Serb- hall. Haiselden Was Morally DAVIS IS RUN DOWN ians Must Fight Greatly WILL CLOSE TODAY It waa the official opening of Atlanta extension of the transconti- and Ethically Right in Re- nental telephone service, that reaches Superior Forces- or Retire from New York to San Francisco. At- fusing to Operate. AND KjUffl BY to Montenegro, Albania or WITH GREAT FROLIC lanta sat and gossiped with San Fran- cisco about the fair, the weather, cur- rent topics and personal amtters. Greece. Chicago came in, too, and so dl( Smoke Prevented Motor- Denver and Salt Lake City and a II tU RIGHT FOR A PHYSICIAN Indications Are That Today unheard-of town out in Nevada, named man From Seeing Man on Wlnnemucca. -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

COMMUNITY BUILDING IN ATLANTA: THE PITTSBURGH / RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITY, 1883-1930 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY RAYMOND F. GORDON DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 1977 T - A-2. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES iii LIST OF MAPS iv INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter I. GENERAL BACKGROUND—ATLANTA1S GROWTH DURING THE POST-RECONSTRUCTION ERA 2 II. THE PITTSBURGH RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITY: THE FORMATION OF A BLACK COMMUNITY, 1883-1930 10 III. THE INTERNAL DYNAMICS OF THE PITTSBURGH RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITY 23 CONCLUSION 37 BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 i i LIST OF TABLES Table Page 1. Pittsburgh Residential Community Population, 1883-1930 . 13 2. Pittsburgh Residential Community Migrant Popula¬ tion, 1900-1910 17 3. Pittsburgh Residential Community Occupational Structure, 1910 18 4. Pittsburgh Residential Community Occupational Structure, 1920 19 5. Pittsburgh Residential Community Occupational Structure, 1930 19 6. Pittsburgh Residential Community Black Property Owners 22 iii LIST OF MAPS Map Page 1. Atlanta's Black Communities 8 2. Residences Occupied by Blacks and Whites in the Pittsburgh Residential Community, 1890 14 3. Residences Occupied by Blacks and Whites in the Pittsburgh Residential Community, 1900 15 4. Residences Occupied by Blacks and Whites in the Pittsburgh Residential Community, 1910 16 5. Black Residential Areas, 1890 25 6. Black Residential Areas, 1920 26 7. The Pittsburgh Residential Community 30 INTRODUCTION The economic progress of Blacks in Atlanta's earliest periods of growth and development was the result of a vigorous drive on the part of leading black and white citizens to bring about a better working relation¬ ship between these two groups. -

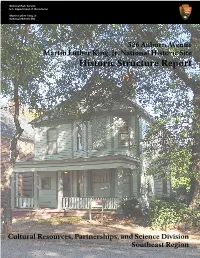

Historic Structure Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report Cultural Resources, Partnerships, and Science Division Southeast Region 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report May 2017 Prepared by: WLA Studio SBC+H Architects Palmer Engineering Under the direction of National Park Service Southeast Regional Offi ce Cultural Resources, Partnerships, & Science Division The report presented here exists in two formats. A printed version is available for study at the park, the Southeastern Regional Offi ce of the National Park Service, and at a variety of other repositories. For more widespread access, this report also exists in a web-based format through ParkNet, the website of the National Park Service. Please visit www.nps. gov for more information. Cultural Resources, Partnerships, & Science Division Southeast Regional Offi ce National Park Service 100 Alabama Street, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404)507-5847 Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site 450 Auburn Avenue, NE Atlanta, GA 30312 www.nps.gov/malu About the cover: View of 526 Auburn Avenue, 2016. 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report Approved By : Superintendent, Date Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Recommended By : Chief, Cultural Resource, Partnerships & Science Division Date Southeast Region Recommended By : Deputy Regional Director, -

Female Historical Figures and Historical Topics

Female Historical Figures and Historical Topics The Georgia Historical Society offers educational materials for teachers to use as resources in the classroom. Explore this document to find highlighted materials related to Georgia and women’s history on the GHS website. In this document, explore the Georgia Historical Society’s educational materials in two sections: Female Historical Figures and Historical Topics. Both sections highlight some of the same materials that can be used for more than one classroom standard or topic. Female Historical Figures There are many women in Georgia history that the Georgia Historical Society features that can be incorporated in the classroom. Explore the readily-available resources below about female figures in Georgia history and discover how to incorporate them into lessons through the standards. Abigail Minis SS8H2 Analyze the colonial period of Georgia’s history. a. Explain the importance of the Charter of 1732, including the reasons for settlement (philanthropy, economics, and defense). c. Evaluate the role of diverse groups (Jews, Salzburgers, Highland Scots, and Malcontents) in settling Georgia during the Trustee Period. e. Give examples of the kinds of goods and services produced and traded in colonial Georgia. • What group of settlers did the Minis family belong to, and how did this contribute to the settling of Georgia in the Trustee Period? • How did Abigail Minis and her family contribute to the colony of Georgia economically? What services and goods did they supply to the market? SS8H3 Analyze the role of Georgia in the American Revolutionary Era. c. Analyze the significance of the Loyalists and Patriots as a part of Georgia’s role in the Revolutionary War; include the Battle of Kettle Creek and Siege of Savannah. -

Cleveland Avenue Corridor Study 2009

2009 City of Atlanta Department of Planning and Community Development Bureau of Planning CLEVELAND AVENUE CORRIDOR STUDY 2009 City of Atlanta Shirley Franklin, Mayor City Council Lisa Borders, Council President Carla Smith, District 1 Kwanza Hall, District 2 Ivory L. Young Jr., District 3 Cleta Winslow, District 4 Natalyn M. Archibong, District 5 Anne Fauver, District 6 Howard Shook, District 7 Clair Muller, District 8 Felicia Moore, District 8 C.T. Martin, District 10 Jim Maddox, District 11 Joyce Sheperd, District 12 Ceasar C. Mitchell, Post 1 At Large Mary Norwood, Post 2 At Large H. Lamar Willis, Post 3 At Large Department of Planning and Community Development James E. Shelby, Commissioner Bureau of Planning Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director Garnett Brown, Assistant Director 55 Trinity Ave, Suite 3350, Atlanta Ga 30303 404-330-6145 http://www.atlantaga.gov/government/planning/burofplanning.aspx P a g e | 2 CLEVELAND AVENUE CORRIDOR STUDY 2009 Project Team Garnett Brown, Bureau of Planning Jessica Lavandier, Bureau of Planning Flor Velarde, Bureau of Planning Jonathan Gelber, Bureau of Planning Alexandra Arkadieva, Bureau of Planning Jewelle Kennedy, Bureau of Planning Valencia Coar, Community Design Center Consultant Team Ken Bleakly, Bleakly Advisory Group JJG Funding Provided by Joyce Sheperd, District 12 The team would like to thank Rosel Fann Recreation Center for the use of the facilities as well as many of the stakeholders that participated in this study. P a g e | 3 CLEVELAND AVENUE CORRIDOR STUDY 2009 Table of Contents Introduction