OBJ (Application/Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Objectivity, Interdisciplinary Methodology, and Shared Authority

ABSTRACT HISTORY TATE. RACHANICE CANDY PATRICE B.A. EMORY UNIVERSITY, 1987 M.P.A. GEORGIA STATE UNIVERSITY, 1990 M.A. UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN- MILWAUKEE, 1995 “OUR ART ITSELF WAS OUR ACTIVISM”: ATLANTA’S NEIGHBORHOOD ARTS CENTER, 1975-1990 Committee Chair: Richard Allen Morton. Ph.D. Dissertation dated May 2012 This cultural history study examined Atlanta’s Neighborhood Arts Center (NAC), which existed from 1975 to 1990, as an example of black cultural politics in the South. As a Black Arts Movement (BAM) institution, this regional expression has been missing from academic discussions of the period. The study investigated the multidisciplinary programming that was created to fulfill its motto of “Art for People’s Sake.” The five themes developed from the program research included: 1) the NAC represented the juxtaposition between the individual and the community, local and national; 2) the NAC reached out and extended the arts to the masses, rather than just focusing on the black middle class and white supporters; 3) the NAC was distinctive in space and location; 4) the NAC seemed to provide more opportunities for women artists than traditional BAM organizations; and 5) the NAC had a specific mission to elevate the social and political consciousness of black people. In addition to placing the Neighborhood Arts Center among the regional branches of the BAM family tree, using the programmatic findings, this research analyzed three themes found to be present in the black cultural politics of Atlanta which made for the center’s unique grassroots contributions to the movement. The themes centered on a history of politics, racial issues, and class dynamics. -

The Atlanta Constitution Circulation

CIRCULATION CIRCULATION LA*T »imi>AT. 47,885 THE ATLANTA CONSTITUTION 49,425 Omar mm* Smmtmf. carrier tttl-nrr, U orata Vol. XLVUJ. — No. 158. ATLANTA. QA., SATUBDAY MORNING, NOVEMBER 20, 1915.—FOURTEEN PAGES. MBKl* c*»i«» «• the atrMta and at »ew« •(•Mete fi e*Bt»> Ca/f'forn/afis and Af/anfans Georgia Woman Is Declared SERBS BEATEN TO PIECES Gossip Over the Telephone Best Farmer in the Southeast At Opening of New Service BY CORONER'S JURY BETWEEN BULGAR HAMMER Across the desert, over the Kockle IN LETTING BABE DIE ANB THE TEUTONIC ANVIL and through western plains last nigh there came contributions to the enter- HARVEST FESTIVAL tainment presented by the Southern Six Physicians, After Hear- Bell Telephone and Telegraph company to 250 city and state officials and busi ness men at the chamber of commerce ing Evidence, Hold Dr. Almost Trapped, the Serb- hall. Haiselden Was Morally DAVIS IS RUN DOWN ians Must Fight Greatly WILL CLOSE TODAY It waa the official opening of Atlanta extension of the transconti- and Ethically Right in Re- nental telephone service, that reaches Superior Forces- or Retire from New York to San Francisco. At- fusing to Operate. AND KjUffl BY to Montenegro, Albania or WITH GREAT FROLIC lanta sat and gossiped with San Fran- cisco about the fair, the weather, cur- rent topics and personal amtters. Greece. Chicago came in, too, and so dl( Smoke Prevented Motor- Denver and Salt Lake City and a II tU RIGHT FOR A PHYSICIAN Indications Are That Today unheard-of town out in Nevada, named man From Seeing Man on Wlnnemucca. -

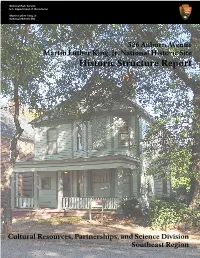

Historic Structure Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report Cultural Resources, Partnerships, and Science Division Southeast Region 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report May 2017 Prepared by: WLA Studio SBC+H Architects Palmer Engineering Under the direction of National Park Service Southeast Regional Offi ce Cultural Resources, Partnerships, & Science Division The report presented here exists in two formats. A printed version is available for study at the park, the Southeastern Regional Offi ce of the National Park Service, and at a variety of other repositories. For more widespread access, this report also exists in a web-based format through ParkNet, the website of the National Park Service. Please visit www.nps. gov for more information. Cultural Resources, Partnerships, & Science Division Southeast Regional Offi ce National Park Service 100 Alabama Street, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404)507-5847 Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site 450 Auburn Avenue, NE Atlanta, GA 30312 www.nps.gov/malu About the cover: View of 526 Auburn Avenue, 2016. 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report Approved By : Superintendent, Date Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Recommended By : Chief, Cultural Resource, Partnerships & Science Division Date Southeast Region Recommended By : Deputy Regional Director, -

Infra-Culture

WHERE WE WANT TO LIVE APA PLANNING WEBCAST SERIES | RYAN GRAVEL, AICP | JUNE 17, 2016 Alexandria, Louisiana Geraldine Keller Gravel with daughter Gerry, 1940s (Gravel family collection) WHERE WE WANT TO LIVE RECLAIMING INFRASTRUCTURE FOR A NEW GENERATION OF CITIES @ryangravel [email protected] www.ryangravel.com RYAN GRAVEL | ST MARTINS PRESS | NEW YORK | 2016 Where We Want to Live Where We Want to Live – Reclaiming Infrastructure for a New Generation of Cities, Ryan Gravel (St Martin’s Press, 2016) @ryangravel www.ryangravel.com @ryangravel Change. Atlanta Beltline. Catalyst Infrastructure. 8 Lessons Why It Matters. @ryangravel Atlanta Beltline (Ryan Gravel, 2006) @ryangravel Atlanta Beltline (Ralph Daniels, 2013) CHANGE. Infra-culture CHANGE. 37 Rue Traversière, Paris (Ryan Gravel, 1994) Infra-culture Baron Haussmann; les Grands Boulevards, Paris Infra-culture Baron Haussmann; demolition for construction of the Avenue de l’Opera, Paris Infra-culture Baron Haussmann; Boulevard Richard Lenoir, Paris Infra-culture Paris (Ryan Gravel, 2010) Infra-culture Paris, a Rainy Day, by Gustave Caillebotte, 1877 Infra-culture Avenue de l’Opera: Morning Sunshine, Camille Pissaro, 1898 IT WAS MORE THAN INFRASTRUCTURE. IT WAS A NEW WAY OF LIFE. Infra-culture Valdosta, Georgia Infra-culture Louisville & Nashville Railroad Virginia Tennessee and Georgia Air Line Infra-culture MARIETTA ATLANTA FORT VALLEY MACON Infra-culture Atlanta, Georgia Infra-culture streetcars built streetcar suburbs (Special Collections Department, Pullen Library, Georgia State University) Infra-culture Woodward Avenue, Detroit, circa 1917 (Detroit Publishing Company) Infra-culture Detroit Superior Bridge (built 1914-1918; source: Library of Congress/courtesy of Turner Publishing) IT WAS MORE THAN INFRASTRUCTURE. IT WAS A WAY OF LIFE. -

Cleveland Avenue Corridor Study 2009

2009 City of Atlanta Department of Planning and Community Development Bureau of Planning CLEVELAND AVENUE CORRIDOR STUDY 2009 City of Atlanta Shirley Franklin, Mayor City Council Lisa Borders, Council President Carla Smith, District 1 Kwanza Hall, District 2 Ivory L. Young Jr., District 3 Cleta Winslow, District 4 Natalyn M. Archibong, District 5 Anne Fauver, District 6 Howard Shook, District 7 Clair Muller, District 8 Felicia Moore, District 8 C.T. Martin, District 10 Jim Maddox, District 11 Joyce Sheperd, District 12 Ceasar C. Mitchell, Post 1 At Large Mary Norwood, Post 2 At Large H. Lamar Willis, Post 3 At Large Department of Planning and Community Development James E. Shelby, Commissioner Bureau of Planning Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director Garnett Brown, Assistant Director 55 Trinity Ave, Suite 3350, Atlanta Ga 30303 404-330-6145 http://www.atlantaga.gov/government/planning/burofplanning.aspx P a g e | 2 CLEVELAND AVENUE CORRIDOR STUDY 2009 Project Team Garnett Brown, Bureau of Planning Jessica Lavandier, Bureau of Planning Flor Velarde, Bureau of Planning Jonathan Gelber, Bureau of Planning Alexandra Arkadieva, Bureau of Planning Jewelle Kennedy, Bureau of Planning Valencia Coar, Community Design Center Consultant Team Ken Bleakly, Bleakly Advisory Group JJG Funding Provided by Joyce Sheperd, District 12 The team would like to thank Rosel Fann Recreation Center for the use of the facilities as well as many of the stakeholders that participated in this study. P a g e | 3 CLEVELAND AVENUE CORRIDOR STUDY 2009 Table of Contents Introduction -

Atlanta Heritage Trails 2.3 Miles, Easy–Moderate

4th Edition AtlantaAtlanta WalksWalks 4th Edition AtlantaAtlanta WalksWalks A Comprehensive Guide to Walking, Running, and Bicycling the Area’s Scenic and Historic Locales Ren and Helen Davis Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Copyright © 1988, 1993, 1998, 2003, 2011 by Render S. Davis and Helen E. Davis All photos © 1998, 2003, 2011 by Render S. Davis and Helen E. Davis All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without prior permission of the publisher. This book is a revised edition of Atlanta’s Urban Trails.Vol. 1, City Tours.Vol. 2, Country Tours. Atlanta: Susan Hunter Publishing, 1988. Maps by Twin Studios and XNR Productions Book design by Loraine M. Joyner Cover design by Maureen Withee Composition by Robin Sherman Fourth Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Manufactured in August 2011 in Harrisonburg, Virgina, by RR Donnelley & Sons in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Davis, Ren, 1951- Atlanta walks : a comprehensive guide to walking, running, and bicycling the area’s scenic and historic locales / written by Ren and Helen Davis. -- 4th ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-56145-584-3 (alk. paper) 1. Atlanta (Ga.)--Tours. 2. Atlanta Region (Ga.)--Tours. 3. Walking--Georgia--Atlanta-- Guidebooks. 4. Walking--Georgia--Atlanta Region--Guidebooks. 5. -

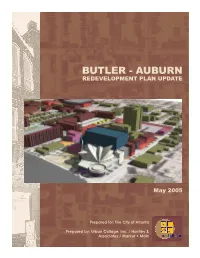

Final Report

BUTLER - AUBURN REDEVELOPMENT PLAN UPDATE May 2005 Prepared for: The City of Atlanta Prepared by: Urban Collage, Inc. / Huntley & Associates / Market + Main Butler - Auburn Redevelopment Plan Update Credits and Acknowledgements Our thanks to the following people for their vision and leadership throughout the redevelopment planning process. City of Atlanta Bureau of Planning James E. Shelby, Acting Comissioner Beverly M. Dockeray-Ojo, Director Flor Velarde, Principal Planner Garnett Brown, Principal Planner Urban Design Commission Karen Huebner, Executive Director Doug Young, Public Information Offi cer Butler-Auburn Leadership Team Project Management Mtamanika Youngblood, Historic District Development Corporation Kwanza Hall, Atlanta Public Schools / Mactec Working Group Frank Catroppa, National Park Service, M. L. King National Historic Site Chuck Lewis, Citizen’s Trust Bank David Patton, NPU-M Janice Perkins, Odd Fellows Building Tony Pope, Architect Consultant Team Stan Harvey, AICP, Principal, Urban Collage, Inc. John Skach, AIA, AICP, Project Manager, Urban Collage, Inc. Bob Begle, Principal Urban Designer, Urban Collage, Inc. Matt Cherry, Project Planner, Urban Collage, Inc. Alix Wilcox, Project Planner, Urban Collage, Inc. Carolina Blenghini, Project Intern, Urban Collage, Inc. Carlos Garcia, Project Intern, Urban Collage, Inc. Kim Brown, Associate, Huntley & Associates Rick Padgett, Associate, Huntley & Associates Aaron Fortner, Principal, Market & Main Butler - Auburn Redevelopment Plan Update 1 Volume One Table of Contents Preface -

The Atlanta Historical Journal

The Atlanta Historical journal Biiekhed UE(fATCKJ„=.._ E<vsf\Poio.<f J Summer/Fall Volume XXVI Number 2-3 The Atlanta Historical Journal Urban Structure, Atlanta Timothy J. Crimmins Dana F. White Guest Editor Guest Editor Ann E. Woodall Editor Map Design by Brian Randall Richard Rothman & Associates Volume XXVI, Numbers 2-3 Summer-Fall 1982 Copyright 1982 by Atlanta Historical Society, Inc. Atlanta, Georgia Cover: The 1895 topographical map of Atlanta and vicinity serves as the background on which railroads and suburbs are highlighted. From the original three railroads of the 1840s evolved the configuration of 1895; since that time, suburban expansion and highway development have dramatically altered the landscape. The layering of Atlanta's metropolitan environment is the focus of this issue. (Courtesy of the Sur veyor General, Department of Archives and History, State of Georgia) Funds for this issue were provided by the Research Division of the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Alumni Association of Georgia State University, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and the University Research Committee of Emory University. Additional copies of this number may be obtained from the Society at a cost of $7.00 per copy. Please send checks made payable to the Atlanta Historical Society to 3101 Andrews Dr. N.W., Atlanta, Georgia, 30305. TABLE OF CONTENTS Urban Structure, Atlanta: An Introduction By Dana F. White and Timothy J. Crimmins 6 Part I The Atlanta Palimpsest: Stripping Away the Layers of the Past By Timothy J. Crimmins 13 West End: Metamorphosis from Suburban Town to Intown Neighborhood By Timothy J. -

A History of the Atlanta Beltline and Its Associated Historic Resources

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Heritage Preservation Projects Department of History 2006 Beltline: A History of the Atlanta Beltline and its Associated Historic Resources Kadambari Badami Janet Barrickman Adam Cheren Allison Combee Savannah Ferguson See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_heritagepreservation Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Badami, Kadambari; Barrickman, Janet; Cheren, Adam; Combee, Allison; Ferguson, Savannah; Frank, Thomas; Garner, Andy; Hawthorne, Mary Anne; Howell, Hadley; Hutcherson, Carrie; McElreath, Rebekah; Marshall, Cherith; Martin, Rebekah; Morrison, Brandy; Serafine, Bethany; and olberT t, Tiffany, "Beltline: A History of the Atlanta Beltline and its Associated Historic Resources" (2006). Heritage Preservation Projects. 4. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_heritagepreservation/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Heritage Preservation Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Kadambari Badami, Janet Barrickman, Adam Cheren, Allison Combee, Savannah Ferguson, Thomas Frank, Andy Garner, Mary Anne Hawthorne, Hadley Howell, Carrie Hutcherson, Rebekah McElreath, Cherith Marshall, Rebekah Martin, Brandy Morrison, Bethany Serafine, -

Historic Structure Report: 550 Auburn Avenue, Martin Luther King, Jr

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site 550Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report Cultural Resources, Partnerships, and Science Division Southeast Region 550 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report May 2017 Prepared by: WLA Studio SBC+H Architects Palmer Engineering Under the direction of National Park Service Southeast Regional Offi ce Cultural Resources, Partnerships, & Science Division The report presented here exists in two formats. A printed version is available for study at the park, the Southeastern Regional Offi ce of the National Park Service, and at a variety of other repositories. For more widespread access, this report also exists in a web-based format through ParkNet, the website of the National Park Service. Please visit www.nps. gov for more information. Cultural Resources, Partnerships, & Science Division Southeast Regional Offi ce National Park Service 100 Alabama Street, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404)507-5847 Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site 450 Auburn Avenue, NE Atlanta, GA 30312 www.nps.gov/malu About the cover: Elevation View of 550 Auburn Avenue from HABS GA,61-ATLA,49- (sheet 7 of 13). 550 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report Approved By : Superintendent, Date Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Recommended By : Chief, Cultural Resource, Partnerships & Science Division Date Southeast Region -

The Atlanta Historical Bulletin

THE ATLANTA HISTORICAL BULLETIN PUBLISHED BY THE ATLANTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY No. 5 APRIL, 1931 The Bulletin is the organ of the Atlanta Historical Society and is sent free to its members. All persons interested in the history of Atlanta are invited to join the Society. Correspondence concerning contributions for the Bulletin should be sent to the Editor, Stephens MitcheU, 605 Peters Building, Atlanta. Applications for membership and dues should be sent to the Secre tary and Treasurer, Miss Ruth Blair, at the office of the State Historian, Rhodes Memorial Hall, 1516 Peachtree Street. Single numbers of the Bulletin may be obtained from the Secretary. The price is $1.00. THE ATLANTA HISTORICAL BULLETIN PUBLISHED BY THE ATLANTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY No. 5 APRIL, 1931 CONTENTS B. F. BOMAR, ATLANTA'S SECOND MAYOR, by T. D. Kllian 5 JEFFERSON DAVIS AT THE UNVEILING OF THE STATUE OF BENJAMIN H. HILL, by Walter McElreath 9 QUEER PLACE NAMES IN OLD ATLANTA, by Eugene M. Mitchell 22 RESIDENTS OF DEKALB COUNTY IN 1833, by Franklin Garrett 31 WHITEHALL TAVERN, by Wilbur G. Kurtz 42 EDITORIAL NOTES 50 ATLANTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY. OFFICERS. WALTER MCELREATH President EUGENE M. MITCHELL Vice-President MISS RUTH BLAIR Secretary and Treasurer Miss TOMMIE DORA BARKER Librarian CURATORS. FORREST ADAIR A. A. MEYER MISS TOMMIE DORA BARKER E. M. MITCHELL MISS RUTH BLAIR MRS. J. K. OTTLEY DR. PHINIZY CALHOUN EDWARD C. PETERS WILLIAM RAWSON COLLIER MRS. R. K. RAMBO JOHN M. GRAHAM MRS. JOHN M. SLATON CLARK HOWELL HOKE SMITH JOHN ASHLEY JONES W. D. THOMSON JAMES L. MAYSON EDGAR WATKINS WALTER MCELREATH WM. -

The 2017 Inman Park Spring Festival & Tour of Homes

THE Inman Park Advocator Atlanta’s Small Town Downtown News • Newsletter of the Inman Park Neighborhood Association April 2017 [email protected] • inmanpark.org • 245 North Highland Avenue NE • Suite 230-401 • Atlanta 30307 Volume 45 • Issue 4 Say Goodbye to the “Suicide Festival Clean-up Lane” on DeKalb Avenue Everyone is invited! It’s Clean-up Day! BY SUSANNA CAPELOUTO • ADVOCATOR STAFF [email protected] What: Pre-Festival Neighborhood Clean-Up DeKalb Avenue is getting an overhaul, thanks to the Renew Atlanta When: Saturday, April 22 • 9:30 a.m. bond referendum voters approved two years ago. The city held a second public meeting about the roadway on March 30th to present Where: Meet at 860 Euclid Ave ideas that the designers came up with after getting input from (free cake and coffee) residents. We’ll Have: Leaf and litter bags The result was a list of options for the road and its intersections You Bring: Gloves, rakes, shovels ranging from roundabouts and advanced traffi c signaling to just two lanes with buffers, bike lanes and turn lanes. Those at the meeting Why: To help our Festival footprint shine were presented with the various designs and asked to vote on their Come to 860 Euclid Avenue for coffee favorite in a non-binding online poll. None of the options included and doughnuts to help clean up the the so called “suicide lane,” the reversible lane that switches neighborhood, and don’t forget direction with rush hour traffi c. to bring your garden gloves if you have any. We will DeKalb Avenue is part of the Complete Streets project which is trying be cleaning up the streets to turn some of the city’s busiest roads into safe corridors not just for together, making sure they cars, but also for bikers and pedestrians.