In Ancient Rome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book I. Title XXVII. Concerning the Office of the Praetor Prefect Of

Book I. Title XXVII. Concerning the office of the Praetor Prefect of Africa and concerning the whole organization of that diocese. (De officio praefecti praetorio Africae et de omni eiusdem dioeceseos statu.) Headnote. Preliminary. For a better understanding of the following chapters in the Code, a brief outline of the organization of the Roman Empire may be given, but historical works will have to be consulted for greater details. The organization as contemplated in the Code was the one initiated by Diocletian and Constantine the Great in the latter part of the third and the beginning of the fourth century of the Christian era, and little need be said about the time previous to that. During the Republican period, Rome was governed mainly by two consuls, tow or more praetors (C. 1.39 and note), quaestors (financial officers and not to be confused with the imperial quaestor of the later period, mentioned at C. 1.30), aediles and a prefect of food supply. The provinces were governed by ex-consuls and ex- praetors sent to them by the Senate, and these governors, so sent, had their retinue of course. After the empire was established, the provinces were, for a time, divided into senatorial and imperial, the later consisting mainly of those in which an army was required. The senate continued to send out ex-consuls and ex-praetors, all called proconsuls, into the senatorial provinces. The proconsul was accompanied by a quaestor, who was a financial officer, and looked after the collection of the revenue, but who seems to have been largely subservient to the proconsul. -

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

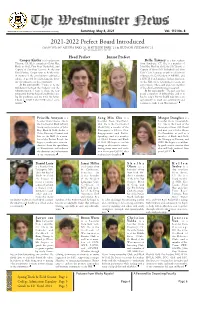

2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced - - - Times

Westminster School Simsbury, CT 06070 www.westminster-school.org Saturday, May 8, 2021 Vol. 110 No. 8 2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced COMPILED BY ALEYNA BAKI ‘21, MATTHEW PARK ‘21 & HUDSON STEDMAN ‘21 CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF, 2020-2021 Head Prefect Junior Prefect Cooper Kistler is a boarder from Bella Tawney is a day student Tiburon, CA. He is a member of John Hay, from Simsbury, CT. She is a member of Black & Gold, First Boys’ Basketball, and John Hay, Black & Gold, the SAC Board, a Captain of First Boys’ lacrosse. As the new Captain of First Girls’ Basketball and First Head Prefect, Cooper aims to be the voice Girls’ Cross Country, as well as a Horizons of everyone in the community to cultivate a volunteer, the Co-President of AWARE, and culture of growth by celebrating the diver- a HOTH board member. In her final year sity of perspectives in the community. on the Hill, she is determined to create an In his own words: “I want to be the environment, where each and every member middleman between the Students and the of the school community feels accepted. Administration. I want to share the new In her own words: “The past year has perspective that we have all established dur- posed a number of difficulties, and it is ing the pandemic, and use it for the better. hard to adapt, but we should take this as an I want to UNITE the NEW school com- opportunity to teach our community and munity." continue to make it our Westminster." Priscilla Ameyaw is a Sung Min Cho is a Margot Douglass is a boarder from Ghana. -

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome William E. Dunstan ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK ................. 17856$ $$FM 09-09-10 09:17:21 PS PAGE iii Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright ᭧ 2011 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. All maps by Bill Nelson. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. The cover image shows a marble bust of the nymph Clytie; for more information, see figure 22.17 on p. 370. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dunstan, William E. Ancient Rome / William E. Dunstan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6833-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6834-1 (electronic) 1. Rome—Civilization. 2. Rome—History—Empire, 30 B.C.–476 A.D. 3. Rome—Politics and government—30 B.C.–476 A.D. I. Title. DG77.D86 2010 937Ј.06—dc22 2010016225 ⅜ϱ ீThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48–1992. Printed in the United States of America ................ -

Vigiles (The Fire Brigade)

insulae: how the masses lived Life in the city & the emperor Romans Romans in f cus With fires, riots, hunger, disease and poor sanitation being the order of the day for the poor of the city of Rome, the emperor often played a personal role in safeguarding the people who lived in the city. Source 1: vigiles (the fire brigade) In 6 AD the emperor Augustus set up a new tax and used the proceeds to start a new force: the fire brigade, the vigiles urbani (literally: watchmen of the city). They were known commonly by their nickname of spartoli; little bucket-carriers. Bronze water Their duties were varied: they fought fires, pump, used by enforced fire prevention methods, acted as vigiles, called a police force, and even had medical a sipho. doctors in each cohort. British Museum. Source 2: Pliny writes to the emperor for help In this letter Pliny, the governor of Bithynia (modern northern Turkey) writes to the emperor Trajan describing the outbreak of a fire and asking for the emperor’s assistance. Pliny Letters 10.33 est autem latius sparsum, primum violentia It spread more widely at first because of the venti, deinde inertia hominum quos satis force of the wind, then because of the constat otiosos et immobilestanti mali sluggishness of the people who, it is clear, stood around as lazy and immobile spectatores perstitisse; et alioqui nullus spectators of such a great calamity. usquam in publico sipo, nulla hama, nullum Furthermore there was no fire-engine or denique instrumentumad incendia water-bucket anywhere for public use, or in compescenda. -

Roman Large-Scale Mapping in the Early Empire

13 · Roman Large-Scale Mapping in the Early Empire o. A. w. DILKE We have already emphasized that in the period of the A further stimulus to large-scale surveying and map early empire1 the Greek contribution to the theory and ping practice in the early empire was given by the land practice of small-scale mapping, culminating in the work reforms undertaken by the Flavians. In particular, a new of Ptolemy, largely overshadowed that of Rome. A dif outlook both on administration and on cartography ferent view must be taken of the history of large-scale came with the accession of Vespasian (T. Flavius Ves mapping. Here we can trace an analogous culmination pasianus, emperor A.D. 69-79). Born in the hilly country of the Roman bent for practical cartography. The foun north of Reate (Rieti), a man of varied and successful dations for a land surveying profession, as already noted, military experience, including the conquest of southern had been laid in the reign of Augustus. Its expansion Britain, he overcame his rivals in the fierce civil wars of had been occasioned by the vast program of colonization A.D. 69. The treasury had been depleted under Nero, carried out by the triumvirs and then by Augustus him and Vespasian was anxious to build up its assets. Fron self after the civil wars. Hyginus Gromaticus, author of tinus, who was a prominent senator throughout the Fla a surveying treatise in the Corpus Agrimensorum, tells vian period (A.D. 69-96), stresses the enrichment of the us that Augustus ordered that the coordinates of surveys treasury by selling to colonies lands known as subseciva. -

Tetrarch Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TETRARCH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ian Irvine | 704 pages | 05 Feb 2004 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781841491998 | English | London, United Kingdom Tetrarch PDF Book Chapter Master Aetheon of the 19th Chapter of the Ultramarines Legion was rumoured to be Guilliman's choice to take up the role of the newest Prince of Ultramar. Eleventh Captain of the Ultramarines Chapter. After linking up with the 8th Parachute Battalion in Bois de Bavent, they proceeded to assist with the British advance on Normandy, providing reconnaissance for the troops. Maxentius rival Caesar , 28 October ; Augustus , c. Year of the 6 Emperors Gordian dynasty — Illyrian emperors — Gallic emperors — Britannic emperors — Cookie Policy. Keep scrolling for more. Luke Now in the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Cesar, Pontius Pilate being governor of Judea, and Herod being tetrarch of Galilee, and his brother In the summer of , Tetrarch got their first taste at extensive touring by doing a day east coast tour in support of the EP. D, Projector and Managing Editor. See idem. Galerius and Maxentius as Augusti of East and West. The four tetrarchs based themselves not at Rome but in other cities closer to the frontiers, mainly intended as headquarters for the defence of the empire against bordering rivals notably Sassanian Persia and barbarians mainly Germanic, and an unending sequence of nomadic or displaced tribes from the eastern steppes at the Rhine and Danube. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. Primarch of the Ultramarines Legion. The armor thickness was increased to a maximum of 16mm using riveted plating, and the Henry Meadows Ltd. -

The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476)

Impact of Empire 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd i 5-4-2007 8:35:52 Impact of Empire Editorial Board of the series Impact of Empire (= Management Team of the Network Impact of Empire) Lukas de Blois, Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt, Elio Lo Cascio, Michael Peachin John Rich, and Christian Witschel Executive Secretariat of the Series and the Network Lukas de Blois, Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn and John Rich Radboud University of Nijmegen, Erasmusplein 1, P.O. Box 9103, 6500 HD Nijmegen, The Netherlands E-mail addresses: [email protected] and [email protected] Academic Board of the International Network Impact of Empire geza alföldy – stéphane benoist – anthony birley christer bruun – john drinkwater – werner eck – peter funke andrea giardina – johannes hahn – fik meijer – onno van nijf marie-thérèse raepsaet-charlier – john richardson bert van der spek – richard talbert – willem zwalve VOLUME 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd ii 5-4-2007 8:35:52 The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476) Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C. – A.D. 476) Capri, March 29 – April 2, 2005 Edited by Lukas de Blois & Elio Lo Cascio With the Aid of Olivier Hekster & Gerda de Kleijn LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. -

Prefekci Pretorianów Cesarza Kommodusa*

Artykuły KLIO. Czasopismo poświęcone dziejom Polski i powszechnym PL ISSN 1643-8191, t. 20 (1) 2012, s. 3–44 Karol Kłodziński (Toruń) Prefekci pretorianów cesarza Kommodusa* ◆ okresie wczesnego Cesarstwa Rzymskiego sprawowanie godności prefekta gwardii pretoriańskiej (dalej: PPO) przez dwóch ekwi- tów stanowiło zasadę sformułowaną przez Oktawiana Augusta W 1 w 2 r. p.n.e. Prefektura gwardii pretoriańskiej w epoce pryncypatu była naj- wyższą godnością w ekwickim cursus honorum2. Nie bez znaczenia jest też fakt, że w tym okresie również senatorowie zostawali PPO3. * Niniejszy artykuł jest częścią obronionej w czerwcu 2009 roku pracy licencjackiej o tak samo brzmiącym tytule. Promotorowi pracy, Panu dr. hab. Szymonowi Olszańcowi dziękuję za wszelkie uwagi i sugestie, jednocześnie podkreślam, że autor pracy ponosi wyłączną odpowie- dzialność za jej treść. 1 Cass. Dio, 55, 10, 10; Mommsen 1877, 831; Passerini 1939, 217; De Laet 1943, 73– –95; Durry 1954, 1620; Syme 1980, 64; Brunt 1983, 59; Watson 1985, 16; Dąbrowa 1990, 364; Le Bohec 1994, 21; Southern 2007, 116. Na temat okoliczności powołania praefecti praeto- rio w 2 roku przed narodzeniem Chrystusa zob. Syme 1939, 357, przypis 3; Ensslin 1954, 2392; Syme 1980, 64; Campbell 1984, 116–117. Pojawiające się w niniejszej pracy daty, jeśli nie za- znaczono, że jest inaczej, odnoszą się do czasów po narodzeniu Chrystusa. 2 Alföldy 2003, 171. W latach 70–235 dla czternastu prefektów Egiptu prefektura gwar- dii pretoriańskiej stanowiła najwyższy szczebel w ekwickim cursus honorum. Przed rokiem 70 tylko dla czterech PPO prefektura Egiptu stanowiła najwyższe stanowisko, Brunt 1975, 124; Demougin 1988, 733. 3 Ensslin 1954, 2398; Absil 1997, 31–32. -

Fall' of Rome

APOCALYPSE, TRANSFORMATION OR MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING? WESTERN SCHOLARSHIP AND THE ‘FALL’ OF ROME (1776-2008)1 Jeroen Wijnendaele In many ways the fifth century CE was one of the most remarkable centuries in European and Mediterranean History.2 An glance at a map of this region around 400 CE shows an empire stretching all the way from the Caucasus to the strait of Gibraltar and from the highlands in Scotland to the Red Sea. A Roman citizen living during the reign of Nero (54-68 CE) would still have recognised those borders as the same as those of his Empire. Yet looking further, around 500 CE, this empire has vanished in the West and been replaced by nearly a dozen barbarian kingdoms. The speed and magnitude of this geopolitical revolution is only comparable with twentieth century, when three empires that for centuries had dominated half of Europe were replaced with nearly twenty nation states. Despite its momentous impact on the shape of history, the fifth century has always been a bit of a black sheep in terms of scholarly attention. For most classicists it is too late, while for most medievalists too early. Furthermore, a lot of classicists feel hesitant to deal with this era. Only in the past few decades has there been a serious revaluation of this period. The old attitude is demonstrated by the original Cambridge Ancient History, the last volume of which stopped with the ascendancy of Constantine I in 324. In French, the period of the Later Roman Empire is usually called Le Bas-Empire—‘The Low Empire’. -

Reading Death in Ancient Rome

Reading Death in Ancient Rome Reading Death in Ancient Rome Mario Erasmo The Ohio State University Press • Columbus Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Erasmo, Mario. Reading death in ancient Rome / Mario Erasmo. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1092-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1092-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Death in literature. 2. Funeral rites and ceremonies—Rome. 3. Mourning cus- toms—Rome. 4. Latin literature—History and criticism. I. Title. PA6029.D43E73 2008 870.9'3548—dc22 2008002873 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1092-5) CD-ROM (978-0-8142-9172-6) Cover design by DesignSmith Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro by Juliet Williams Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI 39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents List of Figures vii Preface and Acknowledgments ix INTRODUCTION Reading Death CHAPTER 1 Playing Dead CHAPTER 2 Staging Death CHAPTER 3 Disposing the Dead 5 CHAPTER 4 Disposing the Dead? CHAPTER 5 Animating the Dead 5 CONCLUSION 205 Notes 29 Works Cited 24 Index 25 List of Figures 1. Funerary altar of Cornelia Glyce. Vatican Museums. Rome. 2. Sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus. Vatican Museums. Rome. 7 3. Sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus (background). Vatican Museums. Rome. 68 4. Epitaph of Rufus. -

Raetia: Las Relaciones Socioeconómicas De Una Provincia Romana Centroeuropea Con Las Provincias Mediterráneas

Raetia: las relaciones socioeconómicas de una provincia romana centroeuropea con las provincias mediterráneas Juan Manuel Bermúdez Lorenzo ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) i a través del Dipòsit Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX ni al Dipòsit Digital de la UB. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX o al Dipòsit Digital de la UB (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) y a través del Repositorio Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR o al Repositorio Digital de la UB.