Australia As a Southern Hemisphere Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Number of Living Species in Australia and the World

Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World 2nd edition Arthur D. Chapman Australian Biodiversity Information Services australia’s nature Toowoomba, Australia there is more still to be discovered… Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study Canberra, Australia September 2009 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Insecta (insects) 23 Plants 43 Viruses 59 Arachnida Magnoliophyta (flowering plants) 43 Protoctista (mainly Introduction 2 (spiders, scorpions, etc) 26 Gymnosperms (Coniferophyta, Protozoa—others included Executive Summary 6 Pycnogonida (sea spiders) 28 Cycadophyta, Gnetophyta under fungi, algae, Myriapoda and Ginkgophyta) 45 Chromista, etc) 60 Detailed discussion by Group 12 (millipedes, centipedes) 29 Ferns and Allies 46 Chordates 13 Acknowledgements 63 Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, etc) 31 Bryophyta Mammalia (mammals) 13 Onychophora (velvet worms) 32 (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) 47 References 66 Aves (birds) 14 Hexapoda (proturans, springtails) 33 Plant Algae (including green Reptilia (reptiles) 15 Mollusca (molluscs, shellfish) 34 algae, red algae, glaucophytes) 49 Amphibia (frogs, etc) 16 Annelida (segmented worms) 35 Fungi 51 Pisces (fishes including Nematoda Fungi (excluding taxa Chondrichthyes and (nematodes, roundworms) 36 treated under Chromista Osteichthyes) 17 and Protoctista) 51 Acanthocephala Agnatha (hagfish, (thorny-headed worms) 37 Lichen-forming fungi 53 lampreys, slime eels) 18 Platyhelminthes (flat worms) 38 Others 54 Cephalochordata (lancelets) 19 Cnidaria (jellyfish, Prokaryota (Bacteria Tunicata or Urochordata sea anenomes, corals) 39 [Monera] of previous report) 54 (sea squirts, doliolids, salps) 20 Porifera (sponges) 40 Cyanophyta (Cyanobacteria) 55 Invertebrates 21 Other Invertebrates 41 Chromista (including some Hemichordata (hemichordates) 21 species previously included Echinodermata (starfish, under either algae or fungi) 56 sea cucumbers, etc) 22 FOREWORD In Australia and around the world, biodiversity is under huge Harnessing core science and knowledge bases, like and growing pressure. -

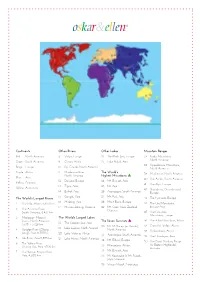

Countries and Continents of the World: a Visual Model

Countries and Continents of the World http://geology.com/world/world-map-clickable.gif By STF Members at The Crossroads School Africa Second largest continent on earth (30,065,000 Sq. Km) Most countries of any other continent Home to The Sahara, the largest desert in the world and The Nile, the longest river in the world The Sahara: covers 4,619,260 km2 The Nile: 6695 kilometers long There are over 1000 languages spoken in Africa http://www.ecdc-cari.org/countries/Africa_Map.gif North America Third largest continent on earth (24,256,000 Sq. Km) Composed of 23 countries Most North Americans speak French, Spanish, and English Only continent that has every kind of climate http://www.freeusandworldmaps.com/html/WorldRegions/WorldRegions.html Asia Largest continent in size and population (44,579,000 Sq. Km) Contains 47 countries Contains the world’s largest country, Russia, and the most populous country, China The Great Wall of China is the only man made structure that can be seen from space Home to Mt. Everest (on the border of Tibet and Nepal), the highest point on earth Mt. Everest is 29,028 ft. (8,848 m) tall http://craigwsmall.wordpress.com/2008/11/10/asia/ Europe Second smallest continent in the world (9,938,000 Sq. Km) Home to the smallest country (Vatican City State) There are no deserts in Europe Contains mineral resources: coal, petroleum, natural gas, copper, lead, and tin http://www.knowledgerush.com/wiki_image/b/bf/Europe-large.png Oceania/Australia Smallest continent on earth (7,687,000 Sq. -

A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States

Buffalo Law Review Volume 4 Number 2 Article 2 1-1-1955 A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States Zelman Cowan Harvard Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Zelman Cowan, A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States, 4 Buff. L. Rev. 155 (1955). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol4/iss2/2 This Leading Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COMPARISON OF THE CONSTITUTIONS OF AUSTRALIA AND THE UNITED STATES * ZELMAN COWAN** The Commonwealth of Australia celebrated its fiftieth birth- day only three years ago. It came into existence in January 1901 under the terms of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, which was a statute of the United Kingdom Parliament. Its origin in a 1 British Act of Parliament did not mean that the driving force for the establishment of the federation came from outside Australia. During the last decade of the nineteenth cen- tury, there had been considerable activity in Australia in support of the federal movement. A national convention met at Sydney in 1891 and approved a draft constitution. After a lapse of some years, another convention met in 1897-8, successively in Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne. -

Fitting in Or Falling Out? Australia's Place in the Asia-Pacific Regional

FITTING IN OR FALLING OUT? AUSTRALIA’S PLACE IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGIONAL ECONOMY Mark Beeson alliance.ussc.edu.au October 2012 US STUDIES CENTRE | ALLIANCE 21 FITTING IN OR FALLING OUT? AUSTRALIA’S PLACE IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGIONAL ECONOMY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ■■ At■the■centre■of■the■new■economic■and■political■realities■that■shape■the■Asia- Pacific■region■is■the■relationship■between■China■and■the■United■States,■Australia’s■ The Alliance 21 Program is a multi-year research initiative respective■principal■trade■partner■and■long-standing■security■guarantor. that examines the historically strong Australia-United ■■ Australia■needs■to■adapt■to■new■market■forces■in■the■international■ States relationship and works to address the challenges economy■in■order■to■escape■the■resource■curse. and opportunities ahead as the alliance evolves in a changing Asia. Based within the United States Studies ■ ■ Despite■the■changing■dynamics■of■the■region■and■the■potential■rivalries■that■may■ Centre at the University of Sydney, the program was exist,■Australia■must■ensure■its■national■interests■continue■to■be■advanced. launched by the Australian Prime Minister in 2011 as a public-private partnership to develop new insights and policy ideas. Australia is caught between two worlds. On one hand, it has the opportunity to take advantage of Asia’s rise and intergrate with Asian economies in order to guarantee its inclusion in the region’s rapid growth. On the other The Australian Government and corporate partners Boral, hand, it faces a series of challenges. Asian economies are developing with great speed and promise. Adapting Dow, News Corp Australia, and Northrop Grumman to changing market complementarity and escaping the resource-curse will be crucial to Australia ‘fitting in’. -

Adaptation of Arab Immigrants to Australia: Psychological, Social' Cultural and Educational Aspects

,l q o") 'no ADAPTATION OF ARAB IMMIGRANTS TO AUSTRALIA: PSYCHOLOGICAL, SOCIAL' CULTURAL AND EDUCATIONAL ASPECTS Nina Maadad,8.4., Dip. Ed., MBd. Studies Research Portfolio submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Bducation in the University of Adelaide, March 2007. ADDENDUM Table B (cont) Eclucational and Occupational Background of Respondents page 45b. ERRATA Page Line AMENDMENT 7 11 delete etc 10 13 l¡r should be lts 26 5 from that shouldbe thctn bottom 34 I4 group should be groups 53 6 from Add century afÍer nineteenth bottom 4 I Tuttisia should be Cairo 8 2 Insefi (Robinson, 1996) 19 1 Delete is and insert has an 2 Delete a 26 4 Delete of 28 2from Delete to the extent and delete lr bottom 70 9 suit case should be suitcase 98 4 there nationality should be their nationality 110 t7 ¿v¿r should be every t20 16 other shouldbe others 160 l7 than shouldbe then 161 t7 Arabian should be Arab r70 4 Arabian should be Arabic 1 9 1 4 from convent should be convert bottom 230 1 Abdullah, S. should be Saeed, A. 234 6 from Taric shouldbe Tarigh bottom TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract lv Declaration vt Äcknowledgements vll Dedication lx INTRODUCTION TO PORTFOLIO Introduction 2 Støtement of the Problem 4 Arabian Cultural Background 7 Arøbían Core Values 7 Islnm ínthe Arab World t4 Hístory of Druze Sect 22 Educatíon ìn the Arab World 26 Muslíms ín Australía 30 Druze ìn Australia 32 Theoretical Framework and Research Method Theoríes of ImmigraÍíon ønd Interactíon 33 Assumptions 38 Research MethodologY 38 S ele ctíon of -

Lesson 1. Introduction to Australia Purpose: to Introduce Students To

Lesson 1. Introduction to Australia Purpose: To introduce students to the continent of Australia. Standards: Goal 2, Standard 2 -To use English to achieve academically in all content areas: Students will use English to obtain, process, construct, and provide subject matter information in spoken and written form. Materials: - items to be put into a travel trunk [a billy (teapot), tea bags, cups, biscuits (crackers), pictures of Australian animals, etc…] - teapot and water - map or globe - construction paper - markers - musical cassette and/or video: Children’s Songs From Around The World (available at local libraries or department stores like Target) Procedures: 1. Before the lesson begins: a. Place the Australian items into the trunk. b. Make tickets to Australia out of construction paper (one for each student). Put a picture of a koala bear on each ticket and write students’ names on them. c. Place a large picture of a koala bear (or other pictures native to Australia) on the trunk. 2. Have students gather around the trunk. Let them guess where their destination might be. Pass out the tickets. 3. Explain that on this adventure, everyone will be a naturalist, (people who are interested in plants and animals around them). 4. Ask what children might know about Australia and record the information (KWL chart). 1 5. Find Australia on a map or globe. a. Identify Australia as a continent b. Look at all the different landscapes (mountains, valleys, rivers). c. Discuss and describe the terms: city, bush, outback, Great Barrier Reef. 6. Examine the trunk. a. Display animal pictures. b. -

Other Rivers

Continents Other Rivers Other Lakes Mountain Ranges Red North America 8 Volga, Europe 22 The Black Sea, Europe 37 Rocky Mountains, North America Green South America 9 Congo, Africa 23 Lake Bajkal, Asia 38 Appalachian Mountains, Beige Europe 10 Rio Grande, North America North America Purple Africa 11 Mackenzie River, The World’s 39 Mackenzie, North America North America Highest Mountains s Blue Asia 40 The Andes, South America 12 Danube, Europe 24 Mt. Everest, Asia Yellow Oceania 41 The Alps, Europe 13 Tigris, Asia 25 K2, Asia White Antarctica 42 Skanderna, (Scandinavia) 14 Eufrat, Asia 26 Aconcagua, South America Europe 15 Ganges, Asia 27 Mt. Fuji, Asia The World’s Longest Rivers 43 The Pyrenees, Europe 16 Mekong, Asia 28 Mont Blanc, Europe 1 The Nile, Africa, 6,650 km 44 The Ural Mountains, 17 Murray-Darling, Oceania 29 Mt. Cook, New Zealand, Europe-Asia 2 The Amazon River, Oceania South America, 6,437 km 45 The Caucasus Mountains, Europe 3 Mississippi- Missouri The World’s Largest Lakes Rivers, North America, The Seven Summits s 46 The Atlas Mountains, Africa 3,778 + 3,726 km 18 The Caspian Sea, Asia 30 Mt. McKinley (or Denali), 47 Great Rift Valley, Africa 19 Lake Superior, North America 4 Yangtze River (Chang North America 48 Drakensberg, Africa Jiang), Asia, 6,300 km 20 Lake Victoria, Africa 31 Aconcagua, South America 49 The Himalayas, Asia 5 Ob River, Asia 5,570 km 21 Lake Huron, North America 32 Mt. Elbrus, Europe 50 The Great Dividing Range 6 The Yellow River 33 Kilimanjaro, Africa (or Eastern Highlands), (Huang Ho), Asia, 4,700 km Australia 7 The Yenisei-Angara River, 34 Mt. -

Inquiry Into Australia's Trade and Investment

Australia’s trade and investment relationships with the countries of Africa Submission 30 INQUIRY INTO AUSTRALIA’S TRADE AND INVESTMENT RELATIONSHIPS WITH THE COUNTRIES OF AFRICA October 2017 Australia’s trade and investment relationships with the countries of Africa Submission 30 INTRODUCTION The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and the Australian Trade and Investment Commission (Austrade) have prepared a joint submission for the Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade inquiry into Australia’s trade and investment relationships with the countries of Africa. This also draws on input provided by Australian diplomatic missions in Africa. This submission covers the fifty-four countries of Africa (see Map at Annex A), and provides country overviews of the key constraints and opportunities to increasing trade and investment with a number of our trading partners (Annex B). Africa is a large continent comprising many nations at very different stages of economic development and stability. Assessments of the opportunities for Australian companies need to balance growth projections against the reality of conflict, commercial risk and weak political and economic governance in many African countries. The overall assessment is positive for increasing engagement by Australian companies in Africa in the coming decades, however for significant increases to occur, sustained improvements in the business-operating environment will be required. A number of the findings of the 2011 Joint Standing Committee on the Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Inquiry into Australia’s relationship with countries of Africa remain relevant today: “Africa is a diverse continent of increasing importance to the world. In geopolitical terms, African countries have increasing influence on international organisations; in resource terms, Africa has vast reserves; in trading terms, Africa’s underutilised arable lands represent great opportunities to feed the world. -

Social and Cultural Links Between Australia and the Middle East 197

8 6RFLDODQG&XOWXUDO/LQNV%HWZHHQ$XVWUDOLD DQGWKH0LGGOH(DVW 8.1 This Chapter examines the social and cultural links which have been established between Australia and the Middle East region, and how these links might be enhanced. 8.2 Social, cultural, educational and other links between Australia and the Middle East have been underpinned by the contribution made to Australia's social and cultural life by migrants from many countries of the region. For most communities from the Middle East, migration to Australia on a large scale has been a fairly recent phenomenon, influenced by major upheavals or historical events—for example, the protracted Arab-Israeli conflict, the 15-year civil war in Lebanon, the Gulf War and the emergence of fundamentalist Islamic states. Against this background, prospective migrants from the region, as from other parts of the world, have been attracted by the opportunities presented by Australia's immigration program. Migration to Australia from the Middle East 8.3 According to data derived from the 1996 census,1 the countries that represent the most significant sources of migration from the Middle East, as a percentage of the total Australian population, are Lebanon, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq. Table 8.1 overleaf shows the size of relevant populations: 1 The latest census was conducted in August 2001. 196 Table 8.1 Populations born in the Middle East, 1986 and 1996 Percentage of Total 1986 1996 Country of Birth Australian Population in Census Census 1996 Bahrain (a) 58 (b) Egypt 30,633 34,139 0.19 Iran 7,498 16,244 0.09 -

The Australian-American Alliance Nor Absolutely Opposed to Australian Interventionist Policies in Southeast Asia

THE AUSTRALIAN Robert Catley -AMERICAN ALLIANCE This paper, here slightly abridged, teas presented to a con ference on “Australia, Vietnam and the Asian Revolution” held in Adelaide in March. The author is a graduate of the London School of Economics and holds a Ph.D. from the Australian National University. He is at present lecturer in international relations at Adelaide University. IN THIS TAPER 1 propose to make a critical examination of the American alliance from an Australian perspective. In that context I shall be only peripherally concerned with that maze of social, economic and diplomatic developments which we term the Asian Revolution. But I would like to make two general observations on that subject which seem relevant to the present discussion. First, there has grown in Australia a school of thought which holds that revolutions a la Vietnam can be expected in a large number of Asian, (and other underdeveloped) countries in the immediate future. I don’t subscribe to this point of view. Revo lutions are extremely difficult things to start and to prosecute; successful revolutions as opposed to palace coups, are exceedingly rare. Most Asian states are rapidly modernising and the power of the modern state to deal with embryonic insurgencies is consider able. In this sense, despite the claims of Peking, time is most likely on the side of the big battalions. The Vietnam insurgency has developed under favourable circumstances and yet has taken nearly three decades and a heavy toll on Vietnamese lives to reach its present stage of considerable strength. The uniqueness of the situation in Vietnam needs to be emphasised both to the romantic armchair revolutionaries, understandably elated by Tet and its aftermath, and to Government supporters, hopefully chastened by recent developments, both of whom have, from different stand points, espoused the domino theory. -

Engagement with Asia: Time to Be Smarter

Securing Australia's Future By Simon Torok and Paul Holper, 208pp, CSIRO Publishing, 2017 2 Engagement with Asia: time to be smarter You can’t do Asia with a Western head, Western thinking. Australian businesses miss opportunities because of a mindset that ‘Aussies know best’. Aussies need to change the way they think about their business. Chinese executive, quoted in SAF11 Australia’s Diaspora Advantage Golden thread Australia must celebrate its relationships in the Asia-Pacific region. We need to engage better and cement Australia’s prominent place in the region. Finding these new opportunities must embrace the invaluable resources of Asian and Pacific communities by improving Australia’s language ability, increasing cultural awareness, building on current export strengths and extending networks and linkages. Key findings This objective distils the interdisciplinary research and evidence from the 11 reports published as part of ACOLA’s Securing Australia’s Future project. To meet this objective, the following six key findings for improving Australia’s smart engagement with Asia and the Pacific need to be addressed: 1. Incentives are required to improve Australia’s linguistic and intercultural competence at school, university, and in the workplace. 2. We need to increase Australia’s ‘soft power’ through cultural diplomacy that updates perceptions of Australia in the Asia-Pacific region, and brings into the 21st century the way Australians see our place in the world. 23 © Australian Council of Learned Academies Secretariat Ltd 2017 www.publish.csiro.au Securing Australia's Future By Simon Torok and Paul Holper, 208pp, CSIRO Publishing, 2017 24 Securing Australia’s Future 3. -

Migration and Integration in Europe, Southeast Asia, and Australia

15 mm front 153 mm 8 mm 13 mm 8 mm front 153 mm 15 mm 15 mm GLOBAL ASIA 6 GLOBAL ASIA Pietsch & Clark (eds) Publications Migration and Integration in Europe, Southeast Asia, and Australia: A Comparative Perspective brings together a group of scholars from a wide range of disciplines to address crucial questions of migration flows and integration in Europe, Southeast Asia, and Australia. Comparative analysis of the three regions and their differing approaches and outcomes yields important insights for each region, as well as provokes new questions and suggests future avenues of study. Juliet Pietsch is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Politics and International Relations, Australian National University. Southeast Asia, and Australia Migration and Integration in Europe, Marshall Clark is a Senior Lecturer at the Research School of Humanities and the Arts of the Australian National University in Canberra. Edited by Juliet Pietsch and Marshall Clark Migration and Integration 240 mm in Europe, Southeast Asia, and Australia A Comparative Perspective ISBN: 978-90-8964-538-8 AUP.nl 9 7 8 9 0 8 9 6 4 5 3 8 8 15 mm Migration and Integration in Europe, Southeast Asia, and Australia Publications The International Institute for Asian Studies is a research and exchange platform based in Leiden, the Netherlands. Its objective is to encourage the interdisciplinary and comparative study of Asia and to promote (inter)national cooperation. IIAS focuses on the humanities and social sciences and on their interaction with other sciences. It stimulates scholarship on Asia and is instrumental in forging research networks among Asia Scholars.