Australia As a Southern Hemisphere Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IOM Regional Strategy 2020-2024 South America

SOUTH AMERICA REGIONAL STRATEGY 2020–2024 IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher: International Organization for Migration Av. Santa Fe 1460, 5th floor C1060ABN Buenos Aires Argentina Tel.: +54 11 4813 3330 Email: [email protected] Website: https://robuenosaires.iom.int/ Cover photo: A Syrian family – beneficiaries of the “Syria Programme” – is welcomed by IOM staff at the Ezeiza International Airport in Buenos Aires. © IOM 2018 _____________________________________________ ISBN 978-92-9068-886-0 (PDF) © 2020 International Organization for Migration (IOM) _____________________________________________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. PUB2020/054/EL SOUTH AMERICA REGIONAL STRATEGY 2020–2024 FOREWORD In November 2019, the IOM Strategic Vision was presented to Member States. It reflects the Organization’s view of how it will need to develop over a five-year period, in order to effectively address complex challenges and seize the many opportunities migration offers to both migrants and society. It responds to new and emerging responsibilities – including membership in the United Nations and coordination of the United Nations Network on Migration – as we enter the Decade of Action to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. -

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

The Civil War Differences Between the North and South Geography of The

Differences Between the North and The Civil War South Geography of the North Geography of the South • Climate – frozen winters; hot/humid summers • Climate – mild winters; long, hot, humid summers • Natural features: • Natural features: − coastline: bays and harbors – fishermen, − coastline: swamps and shipbuilding (i.e. Boston) marshes (rice & sugarcane, − inland: rocky soil – farming hard; turned fishing) to trade and crafts (timber for − inland: indigo, tobacco, & shipbuilding) corn − Towns follow rivers inland! Economy of the North Economy of the South • MORE Cities & Factories • Agriculture: Plantations and Slaves • Industrial Revolution: Introduction of the Machine − White Southerners made − products were made cheaper and faster living off the land − shift from skilled crafts people to less skilled − Cotton Kingdom – Eli laborers Whitney − Economy BOOST!!! •cotton made slavery more important •cotton spread west, so slavery increases 1 Transportation of the North Transportation of the South • National Road – better roads; inexpensive way • WATER! Southern rivers made water travel to deliver products easy and cheap (i.e. Mississippi) • Ships & Canals – river travels fast; steamboat • Southern town sprang up along waterways (i.e. Erie Canal) • Railroad – steam-powered machine (fastest transportation and travels across land ) Society of the North – industrial, urban Society of the South – life agrarian, rural life • Maine to Iowa • Black Northerners − free but not equal (i.e. segregation) • Maryland to Florida & west to Texas − worked -

Struggle for North America Prepare to Read

0120_wh09MODte_ch03s3_s.fm Page 120 Monday, June 4, 2007 10:26WH09MOD_se_CH03_S03_s.fm AM Page 120 Monday, April 9, 2007 10:44 AM Step-by-Step WITNESS HISTORY AUDIO SECTION 3 Instruction 3 A Piece of the Past In 1867, a Canadian farmer of English Objectives descent was cutting logs on his property As you teach this section, keep students with his fourteen-year-old son. As they focused on the following objectives to help used their oxen to pull away a large log, a them answer the Section Focus Question piece of turf came up to reveal a round, and master core content. 3 yellow object. The elaborately engraved 3 object they found, dated 1603, was an ■ Explain why the colony of New France astrolabe that had belonged to French grew slowly. explorer Samuel de Champlain. This ■ Analyze the establishment and growth astrolabe was a piece of the story of the of the English colonies. European exploration of Canada and the A statue of Samuel de Champlain French-British rivalry that followed. ■ Understand why Europeans competed holding up an astrolabe overlooks Focus Question How did European for power in North America and how the Ottawa River in Canada (right). their struggle affected Native Ameri- Champlain’s astrolabe appears struggles for power shape the North cans. above. American continent? Struggle for North America Prepare to Read Objectives In the 1600s, France, the Netherlands, England, and Sweden Build Background Knowledge L3 • Explain why the colony of New France grew joined Spain in settling North America. North America did not Given what they know about the ancient slowly. -

Number of Living Species in Australia and the World

Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World 2nd edition Arthur D. Chapman Australian Biodiversity Information Services australia’s nature Toowoomba, Australia there is more still to be discovered… Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study Canberra, Australia September 2009 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Insecta (insects) 23 Plants 43 Viruses 59 Arachnida Magnoliophyta (flowering plants) 43 Protoctista (mainly Introduction 2 (spiders, scorpions, etc) 26 Gymnosperms (Coniferophyta, Protozoa—others included Executive Summary 6 Pycnogonida (sea spiders) 28 Cycadophyta, Gnetophyta under fungi, algae, Myriapoda and Ginkgophyta) 45 Chromista, etc) 60 Detailed discussion by Group 12 (millipedes, centipedes) 29 Ferns and Allies 46 Chordates 13 Acknowledgements 63 Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, etc) 31 Bryophyta Mammalia (mammals) 13 Onychophora (velvet worms) 32 (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) 47 References 66 Aves (birds) 14 Hexapoda (proturans, springtails) 33 Plant Algae (including green Reptilia (reptiles) 15 Mollusca (molluscs, shellfish) 34 algae, red algae, glaucophytes) 49 Amphibia (frogs, etc) 16 Annelida (segmented worms) 35 Fungi 51 Pisces (fishes including Nematoda Fungi (excluding taxa Chondrichthyes and (nematodes, roundworms) 36 treated under Chromista Osteichthyes) 17 and Protoctista) 51 Acanthocephala Agnatha (hagfish, (thorny-headed worms) 37 Lichen-forming fungi 53 lampreys, slime eels) 18 Platyhelminthes (flat worms) 38 Others 54 Cephalochordata (lancelets) 19 Cnidaria (jellyfish, Prokaryota (Bacteria Tunicata or Urochordata sea anenomes, corals) 39 [Monera] of previous report) 54 (sea squirts, doliolids, salps) 20 Porifera (sponges) 40 Cyanophyta (Cyanobacteria) 55 Invertebrates 21 Other Invertebrates 41 Chromista (including some Hemichordata (hemichordates) 21 species previously included Echinodermata (starfish, under either algae or fungi) 56 sea cucumbers, etc) 22 FOREWORD In Australia and around the world, biodiversity is under huge Harnessing core science and knowledge bases, like and growing pressure. -

Countries and Continents of the World: a Visual Model

Countries and Continents of the World http://geology.com/world/world-map-clickable.gif By STF Members at The Crossroads School Africa Second largest continent on earth (30,065,000 Sq. Km) Most countries of any other continent Home to The Sahara, the largest desert in the world and The Nile, the longest river in the world The Sahara: covers 4,619,260 km2 The Nile: 6695 kilometers long There are over 1000 languages spoken in Africa http://www.ecdc-cari.org/countries/Africa_Map.gif North America Third largest continent on earth (24,256,000 Sq. Km) Composed of 23 countries Most North Americans speak French, Spanish, and English Only continent that has every kind of climate http://www.freeusandworldmaps.com/html/WorldRegions/WorldRegions.html Asia Largest continent in size and population (44,579,000 Sq. Km) Contains 47 countries Contains the world’s largest country, Russia, and the most populous country, China The Great Wall of China is the only man made structure that can be seen from space Home to Mt. Everest (on the border of Tibet and Nepal), the highest point on earth Mt. Everest is 29,028 ft. (8,848 m) tall http://craigwsmall.wordpress.com/2008/11/10/asia/ Europe Second smallest continent in the world (9,938,000 Sq. Km) Home to the smallest country (Vatican City State) There are no deserts in Europe Contains mineral resources: coal, petroleum, natural gas, copper, lead, and tin http://www.knowledgerush.com/wiki_image/b/bf/Europe-large.png Oceania/Australia Smallest continent on earth (7,687,000 Sq. -

Impacts of Four Northern-Hemisphere Teleconnection Patterns on Atmospheric Circulations Over Eurasia and the Pacific

Theor Appl Climatol DOI 10.1007/s00704-016-1801-2 ORIGINAL PAPER Impacts of four northern-hemisphere teleconnection patterns on atmospheric circulations over Eurasia and the Pacific Tao Gao 1,2 & Jin-yi Yu2 & Houk Paek2 Received: 30 July 2015 /Accepted: 31 March 2016 # Springer-Verlag Wien 2016 Abstract The impacts of four teleconnection patterns on at- in summer could be driven, at least partly, by the Atlantic mospheric circulation components over Eurasia and the Multidecadal Oscillation, which to some degree might trans- Pacific region, from low to high latitudes in the Northern mit the influence of the Atlantic Ocean to Eurasia and the Hemisphere (NH), were investigated comprehensively in this Pacific region. study. The patterns, as identified by the Climate Prediction Center (USA), were the East Atlantic (EA), East Atlantic/ Western Russia (EAWR), Polar/Eurasia (POLEUR), and 1 Introduction Scandinavian (SCAND) teleconnections. Results indicate that the EA pattern is closely related to the intensity of the sub- As one of the major components of teleconnection patterns, tropical high over different sectors of the NH in all seasons, atmospheric extra-long waves influence climatic evolutionary especially boreal winter. The wave train associated with this processes. Abnormal oscillations of these extra-long waves pattern serves as an atmospheric bridge that transfers Atlantic generally result in regional or wider-scale irregular atmo- influence into the low-latitude region of the Pacific. In addi- spheric circulations that can lead to abnormal climatic tion, the amplitudes of the EAWR, SCAND, and POLEUR events elsewhere in the world. Therefore, because of their patterns were found to have considerable control on the importance in climate research, considerable attention is given “Vangengeim–Girs” circulation that forms over the Atlantic– to teleconnection patterns on various timescales. -

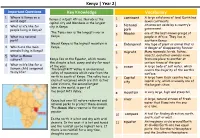

Kenya | Year 2| Important Questions Key Knowledge Vocabulary 1 Where Is Kenya on a a Large Solid Area of Land

Kenya | Year 2| Important Questions Key Knowledge Vocabulary 1 Where is Kenya on a A large solid area of land. Earth has Kenya is in East Africa. Nairobi is the 1 continent world map? seven continents. capital city and Mombasa is the largest An area set aside by a country’s 2 What is life like for city in Kenya. 2 National people living in Kenya? park government. The Tana river is the longest river in 3 Maasai one of the best-known groups of 3 What is a national Kenya. people in Africa. They live in park? southern Kenya Mount Kenya is the highest mountain in 4 Endangered Any type of plant or animal that is 4 Which are the main Kenya. in danger of disappearing forever. animals living in Kenya? 5 migrate Many mammals, birds, fishes, 5 What is Maasai insects, and other animals move culture? Kenya lies on the Equator, which means from one place to another at the climate is hot, sunny and dry for most certain times of the year. What is life like for a 6 of the year. ocean A large body of salt water, which Kenyan child compared 6 The Great Rift Valley is an enormous covers the majority of the earth’s to my life? valley of mountains which runs from the surface. north to south of Kenya. The valley has a 7 Capital A large town. Each country has a chain of volcanoes which are still ‘active’ . city capital city, which is usually one of Lake Victoria, the second largest the largest cities. -

A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States

Buffalo Law Review Volume 4 Number 2 Article 2 1-1-1955 A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States Zelman Cowan Harvard Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Zelman Cowan, A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States, 4 Buff. L. Rev. 155 (1955). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol4/iss2/2 This Leading Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COMPARISON OF THE CONSTITUTIONS OF AUSTRALIA AND THE UNITED STATES * ZELMAN COWAN** The Commonwealth of Australia celebrated its fiftieth birth- day only three years ago. It came into existence in January 1901 under the terms of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, which was a statute of the United Kingdom Parliament. Its origin in a 1 British Act of Parliament did not mean that the driving force for the establishment of the federation came from outside Australia. During the last decade of the nineteenth cen- tury, there had been considerable activity in Australia in support of the federal movement. A national convention met at Sydney in 1891 and approved a draft constitution. After a lapse of some years, another convention met in 1897-8, successively in Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne. -

Fitting in Or Falling Out? Australia's Place in the Asia-Pacific Regional

FITTING IN OR FALLING OUT? AUSTRALIA’S PLACE IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGIONAL ECONOMY Mark Beeson alliance.ussc.edu.au October 2012 US STUDIES CENTRE | ALLIANCE 21 FITTING IN OR FALLING OUT? AUSTRALIA’S PLACE IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGIONAL ECONOMY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ■■ At■the■centre■of■the■new■economic■and■political■realities■that■shape■the■Asia- Pacific■region■is■the■relationship■between■China■and■the■United■States,■Australia’s■ The Alliance 21 Program is a multi-year research initiative respective■principal■trade■partner■and■long-standing■security■guarantor. that examines the historically strong Australia-United ■■ Australia■needs■to■adapt■to■new■market■forces■in■the■international■ States relationship and works to address the challenges economy■in■order■to■escape■the■resource■curse. and opportunities ahead as the alliance evolves in a changing Asia. Based within the United States Studies ■ ■ Despite■the■changing■dynamics■of■the■region■and■the■potential■rivalries■that■may■ Centre at the University of Sydney, the program was exist,■Australia■must■ensure■its■national■interests■continue■to■be■advanced. launched by the Australian Prime Minister in 2011 as a public-private partnership to develop new insights and policy ideas. Australia is caught between two worlds. On one hand, it has the opportunity to take advantage of Asia’s rise and intergrate with Asian economies in order to guarantee its inclusion in the region’s rapid growth. On the other The Australian Government and corporate partners Boral, hand, it faces a series of challenges. Asian economies are developing with great speed and promise. Adapting Dow, News Corp Australia, and Northrop Grumman to changing market complementarity and escaping the resource-curse will be crucial to Australia ‘fitting in’. -

SOUTH AMERICA July/August 2007 GGETTINGETTING SSTARTEDTARTED: Guide

SOUTH AMERICA July/August 2007 GGETTINGETTING SSTARTEDTARTED: Guide Is It Time for a ® South American Strategy? Localization Outsourcing ® and Export in Brazil Doing Business ® in Argentina The Tricky Business ® of Spanish Translation Training Translators ® in South America 0011 GGuideuide SSoAmerica.inddoAmerica.indd 1 66/27/07/27/07 44:13:40:13:40 PPMM SOUTH AMERICA Guide: GGETTINGETTING SSTARTEDTARTED Getting Started: Have you seen the maps where the Southern Hemisphere is at South America the top? “South-up” maps quite often are — incorrectly — referred to as “upside-down,” and it’s easy to be captivated by them. They Editor-in-Chief, Publisher Donna Parrish remind us in the Northern Hemisphere how region-centric we are. Managing Editor Laurel Wagers In this Guide to South America, we focus on doing business and work in Translation Department Editor Jim Healey South America. Greg Churilov and Florencia Paolillo address common trans- Copy Editor Cecilia Spence News Kendra Gray lation misconceptions in dealing with Spanish in South America. Jorgelina Illustrator Doug Jones Vacchino, Nicolás Bravo and Eugenia Conti describe how South American Production Sandy Compton translators are trained. Charles Campbell looks at companies that have Editorial Board entered the South American market with different degrees of success. Jeff Allen, Julieta Coirini, Teddy Bengtsson recounts setting up a company in Argentina. And Bill Hall, Aki Ito, Nancy A. Locke, Fabiano Cid explores Brazil, both as an outsourcing option and an Ultan Ó Broin, Angelika -

Latin America's Missing Middle

Latin America’s missing middle: Rebooting inclusive growth inclusive Rebooting middle: missing Latin America’s Latin America’s missing middle Rebooting inclusive growth May 2019 McKinsey Global Institute Since its founding in 1990, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) has sought to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. As the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, MGI aims to provide leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors with the facts and insights on which to base management and policy decisions. MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth, natural resources, labor markets, the evolution of global financial markets, the economic impact of technology and innovation, and urbanization. Recent reports have assessed the digital economy, the impact of AI and automation on employment, income inequality, the productivity puzzle, the economic benefits of tackling gender inequality, a new era of global competition, Chinese innovation, and digital and financial globalization. MGI is led by three McKinsey & Company senior partners: Jacques Bughin, Jonathan Woetzel, and James Manyika, who also serves as the chairman of MGI. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, Anu Madgavkar, Jan Mischke, Sree Ramaswamy, and Jaana Remes are MGI partners, and Mekala Krishnan and Jeongmin Seong are MGI senior fellows.