Collecting Haudenosaunee Art from the Modern Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Cusick's Sketches of Ancient History of The

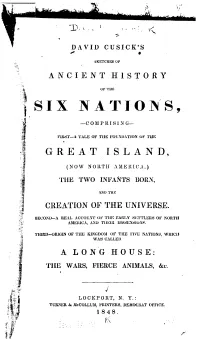

Cus'ick, David The Six Nations The EDITH and LORNE PIERCE COLLECTION of CANADIANA Queens University at Kingston +l±o„ E . 9%& "T DAVID CUSICK'S I SKETCHES OF A N C I N T H1STOR A OF TlM SIX NATIONS, —C M P R I S I N G— FIRST—A TALE OF THE FOtftn&TfOX OF TH« Q R E A T ISLAND, (SOW NORTH AMERICA,) THE TWO INFANTS BORN, AND THK CREATION OF THE UNIVERSE. SECOND—A REAL ACCOUNT OF THE F.AKJ.Y SETTLERS OF NORTH AMERICA, AND THEIR DISSENSIONS TfflRl>—ORIGIH OF T«E= KINGDOM OF THE FIVE NATIONS, WHICH WAS CALLED A LONG H U S E : THE WARS. FIERCE ANIMALS, &c. LOCKPORT, TS~, Y,: TURNER & McCOLLUM, PRINTERS, DEMOCRAT OFFICE. 1 3 4 8 r.v t)OUQLAS LIBRARY Queens University at Kingston Presented by L. MACKAY SMITH ESTATE May 1983 KINGSTON ONTARIO CANADA DAVID CUSICK'S SKETCHES OF ANCIENT HISTORY UK THE SIX NATIONS. —COMPRISING— FIRST—A TALE OF THE FOUNDATION OF THE GREAT ISLAND, (NOW NORTH AMERICA,) THE TWO INFANTS BORN, AND THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSE. SECOND—A REAL ACCOUNT OF THE EARLY SETTLERS OF NORTH AMERICA, AND THEIR DISSENSIONS. THIRD—ORIGIN OF THE KINGDOM OF THE FIVE NATIONS, WHICH WAS CALLED A LONG HOUSE: THE WARS, FIERCE ANIMALS, &c. - LOCKPORZ f TURNER <fe McCOLLUM, FTOWTERS, DEMOCRAT OFFICE, 1 848, 328899 • PREFACE I have been long waiting in hopes that some of my people, who have received an Eng- 3ish education, would have undertaken tho work as to give a sketch of the Ancient History of the Six Nations ; but found no one seemed to concur in the matter, after some hesitation I determined to commence the work ; but found the history involved with fables ; and be- sides, examining myself, finding so small educated that it was impossible for mo to compose the work without much difficulty. -

Round – 2007 – Indigenous Illustration Native American Artists

Indigenous Illustration: Native American Artists and Nineteenth-Century US Print Culture Author(s): Phillip H. Round Source: American Literary History, Vol. 19, No. 2 (Summer, 2007), pp. 267-289 Published by: Oxford University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4496980 Accessed: 15-02-2017 18:14 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Literary History This content downloaded from 140.180.249.58 on Wed, 15 Feb 2017 18:14:04 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Indigenous Illustration: Native American Artists and Nineteenth-Century US Print Culture Phillip H. Round The relationship of Native communities to US print culture during the nineteenth century remains fairly obscure today, some 175 years after the Cherokee Phoenix first saw print in New Echota, Georgia in 1828. In this essay, I would like to focus on one aspect of that history that has received even less notice than movable type-pictorial illustration. The lack of attention paid to printed American Indian illustrations is even more difficult to explain than the lack of critical consideration directed toward early Native books, given that one of the common stereotypes attached to Native utterance is that Indians are image-oriented peoples. -

Writing Native Pasts in the Nineteenth Century A

WRITING NATIVE PASTS IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Daniel Matthew Radus August 2017 © 2017 Daniel Matthew Radus WRITING NATIVE PASTS IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Daniel Matthew Radus, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 Writing Native Pasts in the Nineteenth Century argues that Native American historians responded to the disciplinary emergence of settler-colonial history by challenging the belief that writing afforded exclusive access to the past. As the study of history developed in the nineteenth century, the supposed illiteracy of indigenous communities positioned them outside of historical time. This exclusion served as a facile justification for their territorial displacement and political subjugation. Though studies of historical writing by Native Americans have shown that authors countered these practices by refuting settler-colonial histories and the racist ideologies on which they were based, none has considered how these authors likewise defended their communities by contesting the spurious premise that, because they did not write, indigenous peoples were unable to situate themselves in relation to their pasts. In Writing Native Pasts, I contend that indigenous writers advocated for the territorial and political sovereignty of their communities by insisting on the authority of their historiographical traditions. They did so, I establish, by making the content, structure, and distribution of their narratives amenable to histories whose authority derived from discursive practices that exceeded the formal constraints of the written word. These writers thus countered an intellectual tradition whose origins were inimical to their pasts and hostile to their cultural and political futures. -

Studies in American Indian Literatures Editors James H

volume 23 . number 4 . winter 2011 Studies in American Indian Literatures editors james h. cox, University of Texas at Austin daniel heath justice, University of Toronto Published by the University of Nebraska Press The editors thank the Centre for Aboriginal Initiatives at the University of Toronto and the College of Liberal Arts and the Department of English at the University of Texas for their fi nancial support. subscriptions Studies in American Indian Literatures (SAIL ISSN 0730-3238) is the only scholarly journal in the United States that focuses exclusively on American Indian literatures. SAIL is published quarterly by the University of Nebras- ka Press for the Association for the Study of American Indian Literatures (ASAIL). For current subscription rates please see our website: www.nebraska press.unl.edu. If ordering by mail, please make checks payable to the University of Ne- braska Press and send to The University of Nebraska Press 1111 Lincoln Mall Lincoln, NE 68588-0630 Telephone: 402-472-8536 All inquiries on subscription, change of address, advertising, and other busi- ness communications should be sent to the University of Nebraska Press. A subscription to SAIL is a benefi t of membership in ASAIL. For mem- bership information please contact Jeff Berglund PO Box 6032 Department of English Northern Arizona University Flagstaff, AZ 86011-6032 Phone: 928-523-9237 E-mail: [email protected] submissions The editorial board of SAIL invites the submission of scholarly manuscripts focused on all aspects of American Indian literatures as well as the submis- sion of poetry and short fi ction, bibliographical essays, review essays, and interviews. -

David Cusick's Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations (1828)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 1828 David Cusick’s Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations (1828) David Cusick Paul Royster (editor & depositor) University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Cusick, David and Royster, Paul (editor & depositor), "David Cusick’s Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations (1828)" (1828). Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries. 24. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. DAVID CUSICK’S SKETCHES OF ANCIENT HISTORY OF THE —COMPRISING— F IRST—A TALE OF THE FOUNDATION OF THE GREAT ISLAND, (NOW NORTH AMERICA,) THE TWO INFANTS BORN, AND THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSE. S ECOND—A REAL ACCOUNT OF THE EARLY SETTLERS OF NORTH AMERICA, AND THEIR DISSENTIONS. T HIRD—ORIGIN OF THE KINGDOM OF THE FIVE NATIONS, WHICH WAS CALLED A LONG HOUSE: THE WARS, FIERCE ANIMALS, &c. Second edition of 7,000 copies.—Embelished with 4 engravings. Tuscarora Village: (Lewiston, Niagara co.) 1828 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW-YORK, SS. PPREFACE.R E F A C E . BE IT REMEMBERED, That on the 3d day of January, A. D. 1826, in the 50th year of the Independence of the U. -

David Cusick's Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books in American Studies Zea E-Books 1828 David Cusick's Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations David Cusick Iroquois (Oneida) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeaamericanstudies Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cusick, David, "David Cusick's Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations" (1828). Zea E-Books in American Studies. 10. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeaamericanstudies/10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books in American Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. DAVID CUSICK’S SKETCHES OF ANCIENT HISTORY OF THE SIX NATIONS DAVID CUSICK’S SKETCHES OF ANCIENT HISTORY OF THE —COMPRISING— F IRST—A TALE OF THE FOUNDATION OF THE GREAT ISLAND, (NOW NORTH AMERICA,) THE TWO INFANTS BORN, AND THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSE. S ECOND—A REAL ACCOUNT OF THE EARLY SETTLERS OF NORTH AMERICA, AND THEIR DISSENTIONS. T HIRD—ORIGIN OF THE KINGDOM OF THE FIVE NATIONS, WHICH WAS CALLED A LONG HOUSE: THE WARS, FIERCE ANIMALS, &c. Second edition of 7,000 copies.—Embelished with 4 engravings. Tuscarora Village: (Lewiston, Niagara co.) 1828 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW-YORK, SS. PPREFACE.R E F A C E . BE IT REMEMBERED, That on the 3d day of January, A. D. 1826, in the 50th year of the Independence of the U. S. A. -

Race, Gender and Colonialism: Public Life Among the Six Nations of Grand River, 1899-1939

Race, Gender and Colonialism: Public Life among the Six Nations of Grand River, 1899-1939 by Alison Elizabeth Norman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theory and Policy Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Alison Norman 2010 Race, Gender and Colonialism: Public Life among the Six Nations of Grand River, 1899-1939 Alison Norman Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theory and Policy Studies Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto 2010 Abstract Six Nations women transformed and maintained power in the Grand River community in the early twentieth century. While no longer matrilineal or matrilocal, and while women no longer had effective political power neither as clan mothers, nor as voters or councillors in the post-1924 elective Council system, women did have authority in the community. During this period, women effected change through various methods that were both new and traditional for Six Nations women. Their work was also similar to non-Native women in Ontario. Education was key to women‘s authority at Grand River. Six Nations women became teachers in great numbers during this period, and had some control over the education of children in their community. Children were taught Anglo-Canadian gender roles; girls were educated to be mothers and homemakers, and boys to be farmers and breadwinners. Children were also taught to be loyal British subjects and to maintain the tradition of alliance with Britain that had been established between the Iroquois and the English in the seventeenth century. -

Correspondence of Samuel Kirkland: the Correspondence of Samuel Kirkland, 1765-1793: an Indexed Calendar and Senior Project, by James T

Inventory of correspondence and other documents in the Samuel Kirkland Papers Archives 0000.190 The following is a compilation of several older documents relating to the correspondence of Samuel Kirkland: The Correspondence of Samuel Kirkland, 1765-1793: An Indexed Calendar and Senior Project, by James T. Freeman, Call # HAM COLL HE K62C6 1979, v.1; The Correspondence of Samuel Kirkland, 1794-1795: A Summary and Index of the Kirkland Papers, by John Hinge, Call # HAM COLL HE K6C6 1979; The Correspondence of Samuel Kirkland, 1795-1808: A Summary and Index of the Kirkland Papers, by Christopher S. Barton, Call # HAM COLL HE K62C6 1979. Additions and corrections by Hamilton College Archivist Katherine Collett and Archives Student Assistants John Thickstun and Lauren Humphries-Brooks. Status of Items in Kirkland Collection a) original b) rough draft (K's Handwriting) c) photostat copy of original in Hamilton College Collection d) photostat copy of original not in Ham. Coll. e) typewritten copy of original in Ham. Coll . f) typewritten copy of original not in Ham. Coll. g) handwritten copy (circa-1900's) of document in Ham. Coll. h) handwritten copy (circa-1900's) of document not in Ham. Coll. i) "true copy", handwritten copy contemporary to Kirkland (usually of a document or other important articles.) k) other la. Joseph Wooley to SK Feb. 11, 1765 Onohoquarage (a) Desirous of more supplies. Mentions Peter's trip to New England. lb. SK to "Commanding Officier" Feb., 1765 Kaunandawageah (d1) Gives advice to officier as the intermediary in Seneca prisoner negotiations. 1c. Occom to Rev. Mr. Whitefield May 4, 1765 Lebanon (b) oversize An account of local Indian affairs? (illegible) From the Lothrop/Pickering Papers 1d. -

David Cusick's Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations

'i ~.., ,DAVID CUSICK'S. SKETCHES OF '" ANCIENT HISTORY -'::' OF THE 1SIX .~ -C 0111 PRI SIN G- .....I FlRST-A TALE OF THE FO(j~IUTION OF THE ;::~i GREAT ISLAND, (NOW NOH:£U AMERICA,) ,'ILl THE T\VO INFANTS llOR~, .. ~ A"'D THE ;.~ ~::~ :;~ CREATION OF THE UNIVERSE. ~I> 8ECOi'iU-A REAL ACCOU~T 01" TIlE EARLY SETTLBltS OF NORTH J~ Al\llilUC.\, AND THEm IJISSENSIUN~. THlIW-ORIGIN OF TIlE KINGDO;\I 01" TIlE FIVE NATIONS, WHICH WAS CALLED A LONG HOUSE: . , THE WARS, FIERCE ANIMALS, &c. J LOCKPOHT, N. Y.: TURNER &. McCOLLUll, PRINTERS, DEMOCitAT OFFICE. 1848. r,~ ... I t:-.... PREFACE. I have been l,mg waiting in hopes that some of my people, whobMe .received an Eng lish education, would havo undortaken lhc work as to give a sketch of the Ancient History of Ihe Six Nalions ; bUI found no one seemed 10 concur in the mallcr, after some hesilation I detennined to commence tho work; but found tho history invoh-ed wilh fables; and be aide., examining myself, finding so small educated Ihat it was impossible for mo to compose the work withoul much difficulty. After various reasons I abandoned Ihe idea: I however, took up a resolulion 10 continue lhe work, which I havo lakcn much pains procoring lho ma~rials, and IrBll8laling ilinto English language. I have endeavored to lhrow some ligbl on Ibe b.islory of Ilro origin:I1 populalion of Iho eounlry, which I believe never have been recorded. I hope this littlo work will be acceptable to Iho public. • DAVID CUSICK. TVSC.lROR.\ VIr.r.AGE, Juno 10th, 1825. -

The Tuscarora Migration in 1713 and 2013: Re-Enactment and Revitalization

The Tuscarora Migration in 1713 and 2013: Re-enactment and Revitalization By Paris Deirdre Harper (Under the Direction of Don Nelson) Abstract The focus of this study is the development of the 2013 Tuscarora Migration Project, a three-hundred mile backpacking trip from the Tuscarora’s precontact territory in North Carolina all the way to their home in New York. Tuscarora history has often been expressed in terms of defeat and cultural decline. To the contrary, the 2013 Migration Project not only serves to celebrate the Tuscarora’s survival, but it also has the potential to decolonize Tuscarora history in a way that affirms the present and the future of the community. My study considers how the Migration Project is both an agent and reflection of revitalization for the Tuscarora Nation. My objective is to contribute to the community’s ongoing historical research with an extensive annotated bibliography of primary sources, while also documenting the prevailing attitudes and opinions about life in a Nation undergoing change. INDEX WORDS: Tuscarora, Revitalization, Decolonization, Migration, Historical narratives The Tuscarora Migration in 1713 and 2013: Re-enactment and Revitalization By Paris Harper B.A., Cornell University College of Arts and Sciences, 2010 A Thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Athens, Georgia 2013 © 2013 Paris Deirdre Harper All Rights Reserved THE TUSCARORA MIGRATION IN 1713 AND 2013: RE-ENACTMENT AND REVITALIZATION By PARIS DEIRDRE HARPER Major Professor: Don Nelson Committee: Jennifer Birch Ted Gragson Stephen Kowalewski Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I’d like to acknowledge my advisor, Dr. -

Understanding Post-Traditional Six Nations Militarism, 1814-1930

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-22-2018 12:30 PM Charting Continuation: Understanding Post-Traditional Six Nations Militarism, 1814-1930 Evan Joseph Habkirk The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Hill, Susan Marie The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Evan Joseph Habkirk 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Cultural History Commons, Military History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Habkirk, Evan Joseph, "Charting Continuation: Understanding Post-Traditional Six Nations Militarism, 1814-1930" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5960. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5960 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Abstract Until recently, military historians failed to consider First Nations military participation beyond the settlement of a particular region, including the end War of 1812 in Ontario and Quebec, and the post-Northwest Rebellion era in the Western Provinces. Current historiography of Six Nations military between the end of the War of 1812 and the First World War has also neglected the evolution of First Nations militarism and the voice of First Nations peoples, with most military histories including First Nations participation as contributions to the larger non-First Nations narrative of Canada. -

DAVID CUSICK's 'SKETCHES "Op"Lanciknt HISTORY of Tum

TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARY. Refel'ence Department. TH IS BOOK MUST NOT Bf. TAKf.N OUT OF THE ROO M. DAVID CUSICK'S 'SKETCHES "Op"lANCikNT HISTORY OF TUm -COMPRISING- FIRST-A TALE OF THE FOUNDATION OF THE GREAT ISLAND, (NOW NORTH AMERICA,) THE TWO INFANTS BORN, ./IND THE OB.!:ATION or THE UNI"('EB.S!:. SECOND-A REAL ACCOUNT OF THE EARLY SETTLERS OF NORTH AMERICA, AND 'I.'HEIR DISSENTIONS. rfHIRn-ORIGIN OF THE KINGDON: OF THE FIVE NATIONS, WHICH WAS CALLED A LONG HO"";'JSE: THE WARS, FIERCE ANIMALJ, &c. 'Second edition of 7,000 copies.-Embelished,with 4 engravin~ ~ullt<irn~a 1JillCf1Jf; '~iwistoD, Niagara ~ •• ) . l~~i. l SOUTHERJV'DISTRWT OF NEW-YORK, SS. BE IT REMEMBERED. That on the 3d day of January, A. D. ]B26, in the 5th year of the Inde pendence of the U. S. A. DAVID CU~l('l{, of the said District hath deposited in this oflh~ the title of a Book, the right whereof he claims as Author, in the words following; to "'it: "David Cusick's Sketches of ancient history of the Six Nations: Comprising-First-A tale of the foundation of the Great Island, now North America; the two infants born, and the creation of the Universe. Second-A real account of the early settlers of North America, and their di.sentions. Third-Origin of the kingdom o( the Five Nations, which was called a Long House; the wars, fierce Animals, &c." tn con(ormity to the act of Congress or the United States, enti tled "An act for the encouragp.ment of learning, hy securing the copies of Maps, Charts and Books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned." And also to an Ad, entitled" An Act, suplementary to an Act, entitled, an "An Act for the encouragement of learning, hy securing the cop ies of Maps, Charts and Books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the time therein mentioned, ~nd e:,tendidg the benefits thereof to the arts of designing, engraving and etchin~ historical and other prints." JAMES DILL, Clerk of the Southern Dtstrict of New-York~ 4;ooley & Lathrop.