The Imperial Gazetteer of India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation Forest Department

The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation Forest Department Forest Restoration, Development and Investment Project (FREDIP) Environmental and Social Management Framework (DRAFT FOR CONSULTATIONS) (December 2020) Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................... i List of Tables............................................................................................................................ iv List of Figures .......................................................................................................................... vi Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ vii List of Acronyms and Abbreviations xiv Glossary xvi Conversion Table xviii 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Objectives of Environmental and Social Framework 1 1.2 Scope of Environmental and Social Framework (ESMF) 2 2 Project Description ....................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Project Development Objective 4 2.2 Project Beneficiaries 4 2.3 Project Components and Sub-components 4 2.4 Criteria for Selection of Project Sites in Target Regions 12 2.5 Project Implementation Arrangements 12 3 Policy and Legal Framework ...................................................................................... -

Scanned by Camscanner Scanned by Camscanner Scanned by Camscanner Page 1

Scanned by CamScanner Scanned by CamScanner Scanned by CamScanner Page 1 School-wise pending status of Registration of Class 9th and 11th 2017-18 (upto 10-10-2017) Sl. Dist Sch SchoolName Total09 Entry09 pending_9th Total11 Entry11 1 01 1019 D A V INT COLL DHIMISHRI AGRA 75 74 1 90 82 2 01 1031 ROHTA INT COLL ROHTA AGRA 100 92 8 100 90 3 01 1038 NAV JYOTI GIRLS H S S BALKESHWAR AGRA 50 41 9 0 4 01 1039 ST JOHNS GIRLS INTER COLLEGE 266 244 22 260 239 5 01 1053 HUBLAL INT COLL AGRA 100 21 79 110 86 6 01 1054 KEWALRAM GURMUKHDAS INTER COLLEGE AGRA 200 125 75 200 67 7 01 1057 L B S INT COLL MADHUNAGAR AGRA 71 63 8 48 37 8 01 1064 SHRI RATAN MUNI JAIN INTER COLLEGE AGRA 392 372 20 362 346 9 01 1065 SAKET VIDYAPEETH INTERMEDIATE COLLEGE SAKET COLONY AGRA 150 64 86 200 32 10 01 1068 ST JOHNS INTER COLLEGE HOSPITAL ROAD AGRA 150 129 21 200 160 11 01 1074 SMT V D INT COLL GARHI RAMI AGRA 193 189 4 152 150 12 01 1085 JANTA INT COLL FATEHABAD AGRA 114 108 6 182 161 13 01 1088 JANTA INT COLL MIDHAKUR AGRA 111 110 1 75 45 14 01 1091 M K D INT COLL ARHERA AGRA 98 97 1 106 106 15 01 1092 SRI MOTILAL INT COLL SAIYAN AGRA 165 161 4 210 106 16 01 1095 RASHTRIYA INT COLL BARHAN AGRA 325 318 7 312 310 17 01 1101 ANGLO BENGALI GIRLS INT COLL AGRA 150 89 61 150 82 18 01 1111 ANWARI NELOFER GIRLS I C AGRA 60 55 5 65 40 19 01 1116 SMT SINGARI BAI GIRLS I C BALUGANJ AGRA 70 60 10 100 64 20 01 1120 GOVT GIRLS INT COLL ANWAL KHERA AGRA 112 107 5 95 80 21 01 1121 S B D GIRLS INT COLL FATEHABAD AGRA 105 104 1 47 47 22 01 1122 SHRI RAM SAHAY VERMA INT COLL BASAUNI -

Heisa 2 46 Final.Pmd

Weekly News ang Township, Chin state &mtuya'omudk urÇmudkcsjy&ef &nf&G,fcsufjzifY pDpOfonf[k g g Township, Chin State od&Sd&ygonf/ Lom 2, Hawm 46 g Township, Chin State Cing Khawl Nuam Lai Lo Village, town, Chin Cultural Show vufrSwfrsm;udk oufqdkif&m Community BID Contact ngah lo Nang Sum Mung Tidim Town town, Lian Za Kap KalayTown Ciin Lam Dim Hai Ciin Village town, (17) ck&Sd wm0ef&Sdolrsm;xHwGif wpfapmifvQif &if;*pf 10 rQjzifY Mung Khan Tuan Tui Thang Village Hau Lam Tuang Khuadai Villag Town, Chin State 0,f,l&&dSEdkifaMumif; owif;aumif;yg;vdkufygonf/ Cin Ngaih Thawn Tui Sanzang Village, Suan Sian Lian An Laang Villa Cin Lian Mang Hei Lei Village, Tedim Township, Chin State Khup Suan Thang An Laang Villag Township, Chin State Zam Lian Khual Huapi Village, Tiddim Township, Chin State, Cin Sian Mung Thalmual village Township, Chin State Pum Uk Lian Kodam village, Tonzang township, Chin state, Zam Sum Lian Tunzang village Township, Chin State UN zum ah Interpreter ding mi ki deih Zo Pu Tuizang Village, Tiddim Township, Chin State Thang Leei Mung Suang Pi Village Township, Chin State Thang Mu Mung Se Zang Village, Teddim Township, Chin State Pau Mun Sang Lai Lo Village, T Township, Chin State Khup Sian Khai Tung Zang Village, Tedim Township, Chin State Kham Sian Khai Gor Village, Tidd Township, Chin State UN zum ah Interpreter a sem ding mi kisam a hih Thang Sian Khai Suang Hoih Village, Tiddim Township, Chin Kap Langh Sung Lai Lo Village, T , Tedim, Chin State man in a lunglut te in ACR zum ah sazian a man Bawi Pi Teklui Village, Tedim Township, Chin State Sian Khen Mung Lai Lo Village, T ng village, Tonzang Township, Pau Sang Teak Lui Village, Tiddim Town, Chin State Joseph Tui Khiang Villa g Village, Ton Zang Township lang in hong pia ta un. -

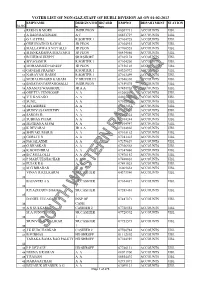

Hubli Voter List-2013

VOTER LIST OF NON-GAZ STAFF OF HUBLI DIVISION AS ON 01-02-2013 EMPNAME DESIGNATIO IDCARD EMPNO DEPARTMENT STATION SL.NO N NO 1 REKHA B MORE JMDR PEON 00207731 ACCOUNTS UBL 2 A BABURATHNAM A C 06431719 ACCOUNTS UBL 3 G LALITHA R SORTER 1 07104728 ACCOUNTS UBL 4 GURUNATH D RAWAL JD PEON 07104935 ACCOUNTS UBL 5 MALLAWWA S NITTALLI JD PEON 07760528 ACCOUNTS UBL 6 SHANKARAPPA M.KUDAGI JD PEON 06434060 ACCOUNTS UBL 7 B I HURALIKUPPI SR RSHORT 07105174 ACCOUNTS UBL 8 SIVAGAMI R R SORTER 1 07104200 ACCOUNTS UBL 9 MOHAMMED HANEEF JD PEON 07456104 ACCOUNTS UBL 10 GANESH PRASAD R SORTER 1 00328972 ACCOUNTS UBL 11 NARAYAN BADDI R SORTER 1 07103499 ACCOUNTS UBL 12 MURALIDHARD KADAM V DRIVER III 07348370 ACCOUNTS UBL 13 BASAVANTAPPAHOSALLI JMDR PEON 07459075 ACCOUNTS UBL 14 ANAND.S.WAGMORE JR A A 07450916 ACCOUNTS UBL 15 GRETTA PUNNOOSE A A 01206564 ACCOUNTS UBL 16 V V KANAGO A A 04695240 ACCOUNTS UBL 17 SUNIL A A 07102768 ACCOUNTS UBL 18 JAYASHREE A A 07103451 ACCOUNTS UBL 19 SRINIVASAMURTHY A A 07103463 ACCOUNTS UBL 20 SAROJA B A A 07104224 ACCOUNTS UBL 21 SUBHAS PUJAR A A 07104248 ACCOUNTS UBL 22 MEGHANA M PAI A A 07104947 ACCOUNTS UBL 23 K DEVARAJ JR A A 07104960 ACCOUNTS UBL 24 SHIVAKUMAR.B A A 07105162 ACCOUNTS UBL 25 GORLI V N A A 07241422 ACCOUNTS UBL 26 NAGALAXMI A A 07279619 ACCOUNTS UBL 27 G.BHASKAR A A 07306568 ACCOUNTS UBL 28 K.GOVINDRAJ A A 07347080 ACCOUNTS UBL 29 B.C.MULLOLLI A A 07476152 ACCOUNTS UBL 30 P MARUTESHACHAR A A 07488816 ACCOUNTS UBL 31 PUJAR R S A A 07491025 ACCOUNTS UBL 32 M G BIRADAR A A 16069638 ACCOUNTS UBL VINAY R -

Forced Migration and Land Rights in Burma

-R&YVQE,SYWMRK0ERHERH4VSTIVX] ,04 VMKLXWEVIMRI\XVMGEFP]PMROIHXSXLIGSYRXV]«W SRKSMRKWXVYKKPIJSVNYWXMGIERHHIQSGVEG]ERHWYWXEMREFPIPMZIPMLSSHW7MRGI[LIRXLI QMPMXEV]VIKMQIXSSOTS[IVSZIVSRIQMPPMSRTISTPILEZIFIIRHMWTPEGIHEWYFWXERXMZIRYQFIV EVIJVSQIXLRMGREXMSREPMX]GSQQYRMXMIWHIRMIHXLIVMKLXXSVIWMHIMRXLIMVLSQIPERHW0ERH GSR´WGEXMSRF]+SZIVRQIRXJSVGIWMWVIWTSRWMFPIJSVQER]WYGL,04ZMSPEXMSRWMR&YVQE -R'3,6)GSQQMWWMSRIH%WLPI]7SYXLSRISJXLI[SVPH«WPIEHMRK&YVQEVIWIEVGLIVWXS GEVV]SYXSRWMXIVIWIEVGLSR,04VMKLXW8LIIRWYMRKVITSVX(MWTPEGIQIRXERH(MWTSWWIWWMSR *SVGIH1MKVEXMSRERH0ERH6MKLXWMR&YVQEJSVQWEGSQTVILIRWMZIPSSOEXXLIOI],04 MWWYIWEJJIGXMRK&YVQEXSHE]ERHLS[XLIWIQMKLXFIWXFIEHHVIWWIHMRXLIJYXYVI Displacement and Dispossession: 8LMWVITSVX´RHWXLEXWYGLTVSFPIQWGERSRP]FIVIWSPZIHXLVSYKLWYFWXERXMEPERHWYWXEMRIH GLERKIMR&YVQEETSPMXMGEPXVERWMXMSRXLEXWLSYPHMRGPYHIMQTVSZIHEGGIWWXSEVERKISJ Forced Migration and Land Rights JYRHEQIRXEPVMKLXWEWIRWLVMRIHMRMRXIVREXMSREPPE[ERHGSRZIRXMSRWMRGPYHMRKVIWTIGXJSV ,04VMKLXW4VSXIGXMSRJVSQ ERHHYVMRK JSVGIHQMKVEXMSRERHWSPYXMSRWXSXLI[MHIWTVIEH ,04GVMWIWMR&YVQEHITIRHYPXMQEXIP]SRWIXXPIQIRXWXSXLIGSRµMGXW[LMGLLEZI[VEGOIHXLI GSYRXV]JSVQSVIXLERLEPJEGIRXYV] BURMA )JJSVXWEXGSRµMGXVIWSPYXMSRLEZIXLYWJEVQIX[MXLSRP]ZIV]PMQMXIHWYGGIWW2IZIVXLIPIWW XLMWVITSVXHIWGVMFIWWSQIMRXIVIWXMRKERHYWIJYPTVSNIGXWXLERLEZIFIIRMQTPIQIRXIHF]GMZMP WSGMIX]KVSYTWMR&YVQE8LIWII\EQTPIWWLS[XLEXRSX[MXLWXERHMRKXLIRIIHJSVJYRHEQIRXEP TSPMXMGEPGLERKIMR&YVQEWXITWGERERHWLSYPHFIXEOIRRS[XSEHHVIWW,04MWWYIW-RTEVXMGYPEV STTSVXYRMXMIWI\MWXXSEWWMWXXLIVILEFMPMXEXMSRSJHMWTPEGIHTISTPIMR[E]W[LMGLPMROTSPMXMGEP -

Title Around the Sagaing Township in Kon-Baung Period All Authors Moe

Title Around the Sagaing Township in Kon-baung Period All Authors Moe Moe Oo Publication Type Local Publication Publisher (Journal name, Myanmar Historical Research Journal, No-21 issue no., page no etc.) Sagaing Division was inhabited by Stone Age people. Sagaing town was a place where the successive kings of Pagan, Innwa and Kon-baungs period constructed religious buildings. Hence it can be regarded as an important place not only for military matters, but also for the administration of the kingdom. Moreover, a considerable number of foreigners were Siamese, Yuns and Manipuris also settled in Sagaing township. Its population was higher than that of Innwa and Abstract lower than that of Amarapura. Therefore, it can be regarded as a medium size town. Agriculture has been the backbone of Sagaing township’s economy since the Pagan period. The Sagaing must have been prosperous but the deeds of land and other mortgages highlight the economic difficulties of the area. It is learnt from the documents concerning legal cases that arose in this area. As Sagaing was famous for its silverware industry, silk-weaving and pottery, it can be concluded that the cultural status was high. Keywords Historical site, military forces, economic aspect, cultural heigh Citation Issue Date 2011 Myanmar Historical Research Journal, No-21, June 2011 149 Around the Sagaing Township in Kon-baung Period By Dr. Moe Moe Oo1 Background History Sagaing Division comprises the tracts between Ayeyarwady and Chindwin rivers, and the earliest fossil remains and remains of Myanmar’s prehistoric culture have been discovered there. A fossilized mandible of a primate was discovered in April 1978 from the Pondaung Formation, a mile to the northwest of Mogaung village, Pale township, Sagaing township. -

Vice-President Thiha Thura U Tin Aung Myint Oo on Inspection Tour of Hkamti District

Established 1914 Volume XIX, Number 268 6th Waning of Pyatho 1373 ME Saturday, 14 January, 2012 Our Three Main * Non-disintegration of * Non-disintegration of * Perpetuation of National Causes the Union National Solidarity Sovereignty Vice-President Thiha Thura U Tin Aung Myint Oo on inspection tour of Hkamti District NAY PYI TAW, 13 Jan—Vice-Presi- dent of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar Thiha Thura U Tin Aung Myint Oo, accompanied by Union ministers, Sagaing Region Chief Minister U Tha Aye, Commander of North-West Command Maj-Gen Soe Lwin, deputy ministers, In- dian Ambassador to Myanmar Dr VS Seshadri and officials, went to Hkamti yesterday. They were welcomed at Hkamti Airport by Sagaing Region Minister for Fi- nance and Revenue U Saw Myint Oo, Chair- man of Naga Self-Administered Zone Lead- ing Body U Rhu San Kyu, Pyithu Hluttaw, Amyotha Hluttaw and Region Hluttaw rep- resentatives of the region, departmental of- ficials, members of social organizations and local national races. At the office of Hkamti District General Administration Department, the Vice-President and party met district and township level departmental officials, members of social organizations and townselders. Hkamti Township Administrator U Aung Kyaw and Deputy Commissioner of the district U Kyaw Than reported on Vice-President of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar Thiha Thura U Tin Aung Myint Oo cordially greeting those locations, areas and administrative matters present at the meeting hall of Hkamti District GAD.—MNA of the township and district. They also gave account of land utilization, rainfall, monsoon get, cultivation and production of rubber, 2012, per capita income, tasks of education the region. -

Jain Worship

?} }? ?} }? ? ? ? ? ? Veer Gyanodaya Granthmala Serial No. 301 ? ? ? ? ? ? VEER GYANODAYA GRANTHMALA ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? This granthmala is an ambitious project of D.J.I.C.R. in ? ? ? ? which we are publishing the original and translated ? ? JAIN WORSHIP ? ? works of Digambar Jain sect written in Hindi, ? ? ? ? ? English, Sanskrit, Prakrit, Apabhramsh, ? ? ? ? ? -:Written by :- ? ? Kannad, Gujrati, Marathi Etc. We are ? ? Pragyashramni ? ? also publishing short story type ? ? ? ? books, booklets etc. in the ? ? Aryika Shri Chandnamati Mataji ? ? interest of beginners ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? and children. ? ? Published in Peace Year-2009, started with the inauguration of ? ? ? ? 'World Peace Ahimsa Conference' by the Hon'ble President of India ? ? -Founder & Inspiration- ? ? ? ? Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil at Jambudweep-Hastinapur on 21st Dec. 2008. ? GANINI PRAMUKH ARYIKA SHIROMANI ? ? ? ? ? ? ? SHRI GYANMATI MATAJI ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? -Guidance- ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Pragya Shramni Aryika Shri Chandnamati ? ? ? ? Mataji ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? -Direction- ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Peethadhish Kshullakratna Shri Moti Sagar Ji ? ? -: Published By :- ? ? ? ? Digambar Jain Trilok Shodh Sansthan ? ? -Granthmala Editor- ? ? ? ? Jambudweep-Hastinapur-250404, Distt.-Meerut (U.P.) ? ? ? ? Karmayogi Br. Shri Ravindra Kumar Jain ? Ph-(01233) 280184, 280236 ? ? ? All Rights Reserved for the Publisher ? ? E-mail : [email protected] ? ? ? ? Website : www.jambudweep.org ? ? ? ? ? ? Composing : Gyanmati Network, ? ? Chaitra Krishna Ekam ? ? ? First Edition Price Jambudweep-Hastinapur -

Flood Inundated Area in Kale Township, Sagaing Region (As of 04.09.2015)

Myanmar Information Management Unit Flood Inundated Area in Kale Township, Sagaing Region (as of 04.09.2015) 94°0'E Kimkai Nanyun India Lahe Hkamti Tuigel Kachin Lay Shi Singtun Yan Myo Aung Homalin Banmauk Indaw Katha Tamu Paungbyin Sagaing Pinlebu Wuntho Tigyaing Mawlaik Kawlin Tonzang Kyunhla Kalewa Kanbalu Kale Tuikhingzang Taze Mingin Ye-U Khin-U Tabayin Chin Shwebo Kani Budalin Shan Wetlet Ayadaw Yinmabin Monywa Sagaing Myinmu Pale Salingyi Chaung-U Myaung Mandalay Magway Yar Za Gyo Reservior Sialthawzang Ngar Se Ngar Maing Dimzang Yar Za Gyo 23°30'N 23°30'N Ngar Se Chauk Maing Khon Thar (East) Taaklam Nan Kyin Saung Khon Thar (West) Mya Lin Mya Sein Oke Kan Chin Kyet Hpa Net Kan Hla Nyein Chan Thar Tedim Shu Khin Thar Thar Si Kan Thar Kan U Kimlai Description: This map shows probable standing flood waters and the analysis was done by UNITAR/UNOSAT. This is a preliminary Kan Gyi analysis and has not yet been validated in the field. Please send ground feedback to MIMU. Son Lar Myaing Data Sources: Satellite Data: Sentinel-1 Zonuamzang Imagery Dates: 4 September 2015 Copyright: Copernicus 2014/ESA Kale Source: Sentinel-1 Scientific Data Hub Aung Kan Thar Yar Analysis: UNITAR - UNOSAT Min Hla Base Map: MIMU, Landsat8 image Sagaing Boundaries: MIMU/WFP Nyaung Kone Place Name: Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) translated by MIMU Pyin Taw U Map ID: MIMU1302v01 Chin Su Nan Han Nwet (Ywar Thit) GLIDE Number: FL-2015-000089-MMR Zozang Production Date: 9 September 2015.A1 Nan Saung Pu Myauk Chaw Taw Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 [email protected] -

RTI Handbook

PREFACE The Right to Information Act 2005 is a historic legislation in the annals of democracy in India. One of the major objective of this Act is to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority by enabling citizens to access information held by or under the control of public authorities. In pursuance of this Act, the RTI Cell of National Archives of India had brought out the first version of the Handbook in 2006 with a view to provide information about the National Archives of India on the basis of the guidelines issued by DOPT. The revised version of the handbook comprehensively explains the legal provisions and functioning of National Archives of India. I feel happy to present before you the revised and updated version of the handbook as done very meticulously by the RTI Cell. I am thankful to Dr.Meena Gautam, Deputy Director of Archives & Central Public Information Officer and S/Shri Ashok Kaushik, Archivist and Shri Uday Shankar, Assistant Archivist of RTI Cell for assisting in updating the present edition. I trust this updated publication will familiarize the public with the mandate, structure and functioning of the NAI. LOV VERMA JOINT SECRETARY & DGA Dated: 2008 Place: New Delhi Table of Contents S.No. Particulars Page No. ============================================================= 1 . Introduction 1-3 2. Particulars of Organization, Functions & Duties 4-11 3. Powers and Duties of Officers and Employees 12-21 4. Rules, Regulations, Instructions, 22-27 Manual and Records for discharging Functions 5. Particulars of any arrangement that exist for 28-29 consultation with or representation by the members of the Public in relation to the formulation of its policy or implementation thereof 6. -

English Version

Eiahth Series. Vol. XLI. No. 16 Thursday, Aueult 18. I'. Sr.van 27. 1918 (Saka) LOK SABHA DEBh (English Version) Eleventh Session (Eightb Lok Sabba) (Val,. 'XLI cOlltatm Nos. 1 J to 20) Lom SABRA SltCllETAIlIAI NE" DELHI ',tce , Rs. : 6.00 (OIUGINAL ENGLISH PROCEEDINGS INCLUDED IN ENGLISH VERSION AND ORIGINAL HI~DI PROCBBDtNGS INCLUDED IN HINDI VeRSION WlLL BB TaRA TEDAS AUTJfORtTATIVB AND NOT THB TRANSLATION THBR170F.l CONTENTS [Eighth Series, Volume XLI, Eleventh Session, 198811910 (Sales)] No.1S, Thursday, August 18, 19881 Sravana 27, 1910 (Saka) COLUMNS Obituary Reference 1 Oral Answers to Questions: 1-38 ·Starred Questions Nos. 304 to 307, 313, 314, 316, and 318. Written Answers to Questions: 38-275 Starred Questions Nos. 308,310 to 312,315, 38-48 317 and 319 to 324. Unstarred Questions Nos. 3106 to 3136, 3138, 3140 48-274 to 3181, 3183 to 3243 and 3245 to 3287. Correcting Statement to usa No.1 0241 dated 9th May, 1988 reo Investment in new projects by Rashtriya Chemicals and Fertilizers. Papers Laid on the Table 275-278 428 Messages From Rajya Sabha 278-279 Matters Under Rule 3n - 279-284 (i) Need to ensure that duty concessions announced on 279-280 Polyester Filament yarn and Fibre yarn in Budget are available to the consumers and weavers- Shri Zainul Basheer (ii) Need to promote tourism in the country - 280-281 Shri Satyendra Narayan Sinha (iii) Need for improvement in the working of Telephone Exchanges 281-282 and installation of electronic exchanges in Akbarpur. Jalalpur and Tanda in Faizabad district- Shri R.P.