The Voice and First Nesting Records of the Zigzag Heron in Ecuador

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provisional List of Birds of the Rio Tahuauyo Areas, Loreto, Peru

Provisional List of Birds of the Rio Tahuauyo areas, Loreto, Peru Compiled by Carol R. Foss, Ph.D. and Josias Tello Huanaquiri, Guide Status based on expeditions from Tahuayo Logde and Amazonia Research Center TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae 1. Great Tinamou Tinamus major 2. White- throated Tinamou Tinamus guttatus 3. Cinereous Tinamou Crypturellus cinereus 4. Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui 5. Undulated Tinamou Crypturellus undulates 6. Variegated Tinamou Crypturellus variegatus 7. Bartlett’s Tinamou Crypturellus bartletti ANSERIFORMES: Anhimidae 8. Horned Screamer Anhima cornuta ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae 9. Muscovy Duck Cairina moschata 10. Blue-winged Teal Anas discors 11. Masked Duck Nomonyx dominicus GALLIFORMES: Cracidae 12. Spix’s Guan Penelope jacquacu 13. Blue-throated Piping-Guan Pipile cumanensis 14. Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 15. Wattled Curassow Crax globulosa 16. Razor-billed Curassow Mitu tuberosum GALLIFORMES: Odontophoridae 17. Marbled Wood-Quall Odontophorus gujanensis 18. Starred Wood-Quall Odontophorus stellatus PELECANIFORMES: Phalacrocoracidae 19. Neotropic Cormorant Phalacrocorax brasilianus PELECANIFORMES: Anhingidae 20. Anhinga Anhinga anhinga CICONIIFORMES: Ardeidae 21. Rufescent Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma lineatum 22. Agami Heron Agamia agami 23. Boat-billed Heron Cochlearius cochlearius 24. Zigzag Heron Zebrilus undulatus 25. Black-crowned Night-Heron Nycticorax nycticorax 26. Striated Heron Butorides striata 27. Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 28. Cocoi Heron Ardea cocoi 29. Great Egret Ardea alba 30. Cappet Heron Pilherodius pileatus 31. Snowy Egret Egretta thula 32. Little Blue Heron Egretta caerulea CICONIIFORMES: Threskiornithidae 33. Green Ibis Mesembrinibis cayennensis 34. Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja CICONIIFORMES: Ciconiidae 35. Jabiru Jabiru mycteria 36. Wood Stork Mycteria Americana CICONIIFORMES: Cathartidae 37. Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 38. Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture Cathartes burrovianus 39. -

A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname

Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen 67 CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed RAP (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Bulletin of Biological Assessment 67 Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION The RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment is published by: Conservation International 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500 Arlington, VA USA 22202 Tel : +1 703-341-2400 www.conservation.org Cover photos: The RAP team surveyed the Grensgebergte Mountains and Upper Palumeu Watershed, as well as the Middle Palumeu River and Kasikasima Mountains visible here. Freshwater resources originating here are vital for all of Suriname. (T. Larsen) Glass frogs (Hyalinobatrachium cf. taylori) lay their -

1000 CHAPTER 6 the Creation Of

1000 CHAPTER 6 The creation of man: creation, not macroevolution – mind the gap. a] Human Anatomy: the generally united creationist school. b] Spotting the wood from the trees - the similarities of homology in promisians, simians, satyr beasts, & men; & the generally united creationist school. c] Soul-talk: i] Distinguishing man from animals - the soul gives man a god focus & capacity for religious belief in the supernatural, and conscience morality seen in a moral code. ii] A revised taxonomy for primates must replace the erroneous twofold taxonomy used for primates. iii] Distinguishing satyr beasts & Man, the Apers & Adamites: A clean cut – like putting a knife through butter. A] Men have souls, animals do not: the APER (African Pre-Edenic Race). B] An Aper Case Study: Australia. C] People “going ape” over the Apers. iv] Where creationists do differ: Subspeciation with respect to man. A] Where are the Adamites in the fossil record? B] Did God create diverse human races? A short preliminary discussion. d] The illusive search for Mitochondrial Adam & Eve: “I know that my genes have ancestors back to Adam: whereas paleontologists can only speculate that fossils they find had descendants.” e] Perforated bones: “Blowing the bone whistle” on “anthropologists” playing loony tunes on “bone flutes.” f] Frustrated Darwinian Macroevolutionists use fraudulent “transitional fossils” against the generally United Creationist School. (Chapter 6) a] Human Anatomy: the generally united creationist school. In 1802, creationist Paley used as a teleological argument of the human body, saying, “For my part, I take my stand in human anatomy 1.” This validly looks to the complexities of human biology to see a design pointing to a Divine Designer. -

Mammalian and Avian Diversity of the Rewa Head, Rupununi, Southern Guyana

Biota Neotrop., vol. 11, no. 3 Mammalian and avian diversity of the Rewa Head, Rupununi, Southern Guyana Robert Stuart Alexander Pickles1,2, Niall Patrick McCann1 & Ashley Peregrine Holland1 1Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, School of Biosciences,Cardiff University, Museum Avenue, Cardiff, Wales, CF103AX Rupununi River Drifters, Karanambu Ranch, Lethem Post Office, Region 9, Rupununi Guyana 2Corresponding author: Robert Stuart Alexander Pickles, e-mail: [email protected] PICKLES, R.S.A., McCANN, N.P. & HOLLAND, A.L. Mammalian and avian diversity of the Rewa Head, Rupununi, Southern Guyana. Biota Neotrop. 11(3): http://www.biotaneotropica.org.br/v11n3/en/abstract?in ventory+bn00911032011 Abstract: We report the results of a short expedition to the remote headwaters of the River Rewa, a tributary of the River Essequibo in the Rupununi, Southern Guyana. We used a combination of camera trapping, mist netting and spot count surveys to document the mammalian and avian diversity found in the region. We recorded a total of 33 mammal species including all 8 of Guyana’s monkey species as well as threatened species such as lowland tapir (Tapirus terrestris), giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) and bush dog (Speothos venaticus). We recorded a minimum population size of 35 giant otters in five packs along the 95 km of river surveyed. In total we observed 193 bird species from 47 families. With the inclusion of Smithsonian Institution data from 2006, the bird species list for the Rewa Head rises to 250 from 54 families. These include 10 Guiana Shield endemics and two species recorded as rare throughout their ranges: the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) and crested eagle (Morphnus guianensis). -

Codon Usage and Molecular Phylogenetics Studies of Codon Usage and Molecular Phylogenetics Using

CODON USAGE AND MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS STUDIES OF CODON USAGE AND MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS USING MITOCHONDRIAL GENOMES By WENLI JIA, B.Sc., M.ENG. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science McMaster University @Copyright by Wenli Jia, December 2007 MASTER OF SCIENCE (2007) McMaster University (Computational Engineering and Science) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Studies of Codon Usage and Molecular Phylogenetics Using Mitochon- drial Genomes AUTHOR: Wenli Jia, B.Sc., M.Eng. SUPERVISOR: Dr. Paul G. Higgs NUMBER OF PAGES: xxiv, 170 ii Abstract Three pieces of work are contained in this thesis. OGRe is a relational database that stores mitochondrial genomes of animals. The database has been operational for approximately five years and the number of genomes in the database has expanded to over 1000 in this period. However, sometimes, new genomes can not be added to the database because of small errors in the source ffies. Several improvements to the update method and the organizational structure of OGRe have been done, which are presented in the first part of this thesis. The second part of this thesis is a study on codon usage in mitochondrial genomes of mammals and fish. Codon usage bias can be caused by mutation and translational selection. In this study, we use some statistical tests and likelihood-based tests to determine which factors are most important in causing codon bias in mitochondrial genomes of mammals and fish. It is found that codon usage patterns seem to be determined principally by complex context-dependent mutational effects. -

Cristalino Lodge Alta Floresta, Mato Grosso State - Brazil

AMAZON FOREST - Cristalino Lodge Alta Floresta, Mato Grosso State - Brazil Date: July 10th to 15th – 2017 (6 days / 5 nights) Maximum Group Size: 12 Participants (Minimum of 4 people to run this tour) Guide: Edson Endrigo or André de Luca or English speaking birding guide Reservation: [email protected] ABOUT CRISTALINO LODGE Home to nearly 600 bird species, the Alta Floresta region of the Southern Amazon basin is a world class destination. A weeklong stay at the award winning Cristalino Jungle Lodge is an unforgettable experience, made memorable by the friendly service, excellent food, charming accommodations, and the great birding. More than 20 km of trails access various types of forest, from vine‑laden bamboo thickets (Manu Antbird, Chestnut‑throated Spinetail, Dusky‑tailed Flatbill), to sandy igapó (Blue‑crowned Trogon, Flame‑crested Manakin), to tall terra firme (Musician Wren, Collared Puffbird), and stunted forest a top rocky domes (Brown‑banded Puffbird, White‑browed Purpletuft, Natterer’s Slaty‑Antshrike). Trails in the Forest: Gray Tinamou, Cryptic Forest-Falcon, Strong-billed Woodcreeper, Black-spotted Bare-eye, Rufous-capped Nunlet, Blue-cheeked Jacamar, Collared Trogon, Dot-backed and Striated Antbird, Great Jacamar, Musician Wren, Red-headed Manakin, Dusky-tailed Flatbill, Royal Flycatcher, Snow-capped Manakin, Spot-winged and Fasciated Antshrike, White-crested Spadebill, White-winged Shrike-Tanager and many other species. With luck, we will find a swarm of army ants raiding on the forest floor, where we can find the endemic Bare‑eyed Antbird and Brown‑winged Trumpeters, alongside other antbirds and woodcreepers and many other species. Boat Trip: These trips on the Cristalino and Teles Pires rivers usually find various herons, swallows and sometimes mammals like tapir, capybara, and two species of otters. -

Systematics and Evolutionary Rela Tionships Among the Herons (~Rdeidae)

MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, NO. 150 Systematics and Evolutionary Rela tionships Among the Herons (~rdeidae) BY ROBERT B. PAYNE and CHRISTOPHER J. RISLEY Ann Arbor MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN August 13, 1976 MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN FRANCIS C. EVANS, EDITOR The publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, consist of two series-the Occasional Papers and the Miscellaneous Publications. Both series were founded by Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradshaw H. Swales, and Dr. W. W. Newcomb. The Occasional Papers, publication of which was begun in 1913, serve as a medium for original studies based principally upon the collections in the Museum. They are issued separately. When a sufficient number of pages has been printed to make a volume, a title page, table of contents, and an index are supplied to libraries and individuals on the mailing list for the series. The Miscellaneous Publications, which include papers on field and museum techniques, monographic studies, and other contributions not within the scope of the Occasional Papers, are published separately. It is not intended that they be grouped into volumes. Each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. A complete list of publications on Birds, Fishes, Insects, Mammals, Mollusks, and Reptiles and Amphibians is available. Address inquiries to the Director, Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109. MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, NO. 150 Systematics and Evolutionary Relationships Among the Herons (Ardeidae) BY ROBERT B. PAYNE and CHRISTOPHER J. RISLEY Ann Arbor MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN August 13, 1976 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION ....................................... -

Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club

Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club Volume 133 No. 3 September 2013 FORTHCOMING MEETINGS See also BOC website: http://www.boc-online.org BOC MEETINGS are open to all, not just BOC members, and are free. Evening meetings are held in an upstairs room at The Barley Mow, 104, Horseferry Road, Westminster, London SW1P 2EE. The nearest Tube stations are Victoria and St James’s Park; and the 507 bus, which runs from Victoria to Waterloo, stops nearby. For maps, see http://www.markettaverns.co.uk/the_barley_mow. html or ask the Chairman for directions. The cash bar will open at 6.00 pm and those who wish to eat after the meeting can place an order. The talk will start at 6.30 pm and, with questions, will last about one hour. It would be very helpful if those who are intending to come would notify the Chairman no later than the day before the meeting and preferably earlier. 24 September 2013—6.30 pm—Dr Roger Saford—Recent advances in the knowledge of Malagasy region birds Abstract: The Malagasy region comprises Madagascar, the Seychelles, the Comoros and the Mascarenes (Mauritius, Reunion and Rodrigues), six more isolated islands or small archipelagos, and associated sea areas. It contains one of the most extraordinary and distinctive concentrations of biological diversity in the world. The last 20 years have seen a very large increase in the level of knowledge of, and interest in, the birds of the region. This talk will draw on research carried out during the preparation of the first thorough handbook to the region’s birds—487 species—to be compiled since the late 19th century. -

A New Genus and Species of Heron (Aves: Ardeidae) from the Late Miocene of Florida

A NEW GENUS AND SPECIES OF HERON (AVES: ARDEIDAE) FROM THE LATE MIOCENE OF FLORIDA David W. Steadman1 and Oona M. Takano2 ABSTRACT From the recently discovered Montbrook locality, Levy County, Florida (late Miocene; late Hemphillian land mammal age), a complete coracoid and nearly complete scapula represent a large heron that we name Taphophoyx hodgei new genus and species. While the phylogenetic affinities of T. hodgei are not well resolved, the tiger-herons Tigrisoma spp. or boat-billed heron Cochlearius cochlearius (both Neotropical) may be the closest living relative(s) of Taphophoyx, based in large part on several shared characters of the facies articularis clavicularis and facies articularis humeralis. Nevertheless, the coracoid of Taphophoyx has a uniquely prominent facies articularis humeralis and a uniquely sterno-ventral surface of corpus coracoidei. All 21 taxa of birds recorded thus far from Montbrook (mostly aquatic forms such as swans, ducks, geese, grebes, cormorants, ibises, sandpipers, etc.) probably represent extinct species, although Taphophoyx hodgei is the only one assigned to an extinct genus. Key words: Florida, Montbrook, late Miocene, heron, Ardeidae, new taxa. This published work and the nomenclatural acts it contains have been registered in ZooBank, the online registration system for the ICZN. The ZooBank Publication number for this issue is BCAF821D-656A-4327- 95C1-F2F775F8A959. Published On-line: April 6, 2019 Open Access Download at https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/bulletin/publications/ ISSN 2373-9991 Copyright © 2019 by the Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida. All rights reserved. Text, images and other media are for nonprofit, educational, or personal use of students, scholars, and the public. -

Birding List

B I R D C H E C K L I S T THE MAGIC BIRDING & BIRD PHOTO CIRCUIT OF ECUADOR Checklist by: Luis Alcivar & Genesis Lopez Works Cited: BirdLife International (2004). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved on 10 feb 2010. Locations: Paramo and Treeline Forest: Antisana (A) - Cayambe Coca & Papallacta Pass (P) Upper Andean Forest: San Jorge Quito (Q) - Yanacocha Road (Y) Dry Inter-Andean Forest: Old Hypodrome, Pululahua Crater & Jerusalem Ecological Park (J) (Western) Andean Cloud Forest: San Tadeo Road, Santa Rosa Road, & San Jorge Tandayapa (T) (Western) Upper Tropical Forest: Umbrellabird LEK & San Jorge Milpe (M) (Western) Lower Tropical Forest: Pedro Vicente Maldonado & Silanche (V) Pacific Lowlands (Coast): San Jorge Estero Hondo & surrounding fresh water lakes (E) (Eastern) Andean Cloud Forest: Cuyuja River, Baeza, Borja, San Jorge Guacamayos, & San Jorge Cosanga (C) Upper Amazon Basin: Ollin/Narupa Reserve (O) Napo-Galeras & Sumaco National Park (S) Lower Amazon Basin (Amazon Lowlands): San Jorge Sumaco Bajo, Limoncocha Biological Reserve, Napo River & Yasuni National Park (Z) Abundance: (1) Common (2) Fairly Common (3) Uncommon (4) Rare (5) Very Rare (6) Extremely Rare > 5 observations 1 2 3 4 5 6 Endemism: N: National Endemic - Cho: Choco region (NW Ecuador and W Colombia only) - Tum: Tumbesian region (SW Ecuador and NW Peru only) E/C: Ecuador and Colombia only - (E/P) Ecuador and Peru only - (E/P/C) Ecuador, Peru & Colombia only Status: LC: Least Concern NT: Near Threatened VU: Vulnerable -

Flock Formation and the Role of Plumage Colouration in Ardeidae

683 Flock formation and the role of plumage colouration in Ardeidae M. Clay Green and Paul L. Leberg Abstract: It has been hypothesized that white plumage facilitates flock formation in Ardeidae. We conducted four ex- periments using decoys to test factors involved in attracting wading birds to a specific pond. The first three experi- ments tested the effects of plumage colouration, flock size, and species-specific decoys on flock formation. The fourth experiment examined intraspecific differences in flock choice between the two colour morphs of the reddish egret, Egretta rufescens (Gmelin, 1789). Wading birds landed at flocks of decoys more often than single or no decoys (P < 0.001) but exhibited no overall attraction to white plumage (P > 0.05). White-plumaged species were attracted to white decoys (P < 0.001) and dark-plumaged species were attracted to dark decoys (P < 0.001). Snowy egrets (E. thula (Molina, 1782)), great egrets (Ardea alba L., 1758), and little blue herons (E. caerulea (L., 1758)) landed more often at ponds that contained decoys resembling conspecifics. At the intraspecific level, all observed reddish egrets selected flocks with like-plumaged decoys. Our results suggest that plumage colouration is an attractant for species with similar plumage, but white plumage is not an attractant for all wading bird species. White plumage may facilitate flock forma- tion in certain species but does not serve as a universal attractant for wading birds of varying plumage colouration and size. Résumé : On a avancé l’hypothèse qui veut que le plumage blanc des ardéidés facilite la formation des volées. Nous avons fait quatre expériences à l’aide de leurres afin de déterminer les facteurs impliqués dans l’attirance des échassiers pour un étang particulier. -

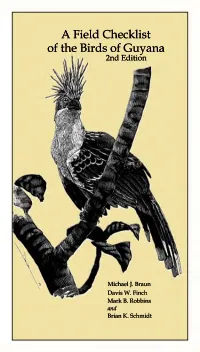

A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2Nd Edition

A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2nd Edition Michael J. Braun Davis W. Finch Mark B. Robbins and Brian K. Schmidt Smithsonian Institution USAID O •^^^^ FROM THE AMERICAN PEOPLE A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2nd Edition by Michael J. Braun, Davis W. Finch, Mark B. Robbins, and Brian K. Schmidt Publication 121 of the Biological Diversity of the Guiana Shield Program National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC, USA Produced under the auspices of the Centre for the Study of Biological Diversity University of Guyana Georgetown, Guyana 2007 PREFERRED CITATION: Braun, M. J., D. W. Finch, M. B. Robbins and B. K. Schmidt. 2007. A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana, 2nd Ed. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. AUTHORS' ADDRESSES: Michael J. Braun - Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD, USA 20746 ([email protected]) Davis W. Finch - WINGS, 1643 North Alvemon Way, Suite 105, Tucson, AZ, USA 85712 ([email protected]) Mark B. Robbins - Division of Ornithology, Natural History Museum, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 66045 ([email protected]) Brian K. Schmidt - Smithsonian Institution, Division of Birds, PO Box 37012, Washington, DC, USA 20013- 7012 ([email protected]) COVER ILLUSTRATION: Guyana's national bird, the Hoatzin or Canje Pheasant, Opisthocomus hoazin, by Dan Lane. INTRODUCTION This publication presents a comprehensive list of the birds of Guyana with summary information on their habitats, biogeographical affinities, migratory behavior and abundance, in a format suitable for use in the field. It should facilitate field identification, especially when used in conjunction with an illustrated work such as Birds of Venezuela (Hilty 2003).