News Media Framing of Champion Cyclists and Doping Suspicion in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tour De France - 11

Biomatematický model BMM: Tour de France - 11. etapa Na programu jubilejní 100 Tour de France chyběl klasický prolog a tak jsme vhodnou trať pro BMM museli počkat až do 11. etapy, kdy přišla na řadu první individuální časovka. Náročnost 33km dlouhé trati notně zvyšoval silný vítr, se kterým se všichni závodníci potýkali. Hned v úvodu nasadil nepřekonatelnou laťku favorizovaný Tony Martin (Omega Pharma-Quick step), se kterým vyrovnanou partii sehrál jen žlutý Chris Froome (Sky Procycling), výrazně tím navyšující své celkové vedení. Mezi ostatními jezdci top 10 to byla vyrovnaná bitva. Roman Kreuziger (Team Saxo-Tinkoff) zajel výborně a udržel celkové 5. místo a samozřejmě velmi emotivním zážitkem pro všechny byla ostrá jízda paralympika Jirky Ježka v roli oficiálního předjezdce. Jak se mezi špalíry diváků dařilo na trati jezdcům v programu BMM? Vítr nám dal zabrat, co? Více ve výsledkové listině na další straně Zajímavá videa z etapy např.: http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=0zvvJa9D7aM http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=joit1IgOd4U 1 Tony Martin GER Omega Pharma‐Quick Step 0:36:29 54,3 69 Andreas Klöden GER RadioShack Leopard 0:40:11 49,3 137 Christophe Le Mevel FRA Cofidis, Solutions Credits 0:41:32 47,7 2 Christopher Froome GBR Sky Procycling 0:36:41 54,0 70 Davide Malacarne ITA Team Europcar 0:40:11 49,3 138 Gert Steegmans BEL Omega Pharma‐Quick Step 0:41:33 47,7 3 Thomas De Gendt BEL Vacansoleil‐DCM Pro Cycling 0:37:30 52,8 71 Matteo Tosatto ITA Team Saxo‐Tinkoff 0:40:16 49,2 139 André Greipel GER Lotto Belisol 0:41:34 -

Case – Tdf Diagnostic Hypotheses 2013

____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Froome's performances since the Vuelta 11 are so good that he should be considered a Grand Tour champion. Grand Tour champions who didn't benefit from game-changing drugs (GTC) usually display a high potential as junior athletes. Supporting evidence: Coppi first won the Giro at 20 Anquetil first won the Grand Prix des Nations at 19 Merckx won the world's road at 19 Hinault won the Giro and Tour at 24 LeMond showed amazing talent at just 15 Fignon led the Giro and won the Critèrium national at 22 No display of early talent H: Froome rode the 2013 TdF 'clean' ~H: Froome didn't ride the 2013 TdF 'clean' Reason: Because p(D|H) = Objection: But that's because he grew up in Evaluation Froome didn't display a high Froome's first major wins a country with no cycling activity per say and p(D|~H) = potential as a junior athlete. were at age 26, which is he took up road racing late. quite late in cycling. Cognitive dissonance (additional condition): Being clean, Froome performs at a Grand Tour champion level despite not having shown great potential as a junior athlete. Requirement: it is possible to be a clean Grand Tour champion without showing high potential as a junior athlete. Armstrong's performance in the TdF: DNF, DNF, 36, DNF, DNS [cancer], DNS [cancer], 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 3, 23 Sudden metamorphoses from 'middle of the pack' to 'champion' are Team Sky's director Brailsford: "We also look at the history of the guy, his usually seen in dopers. -

Relation Between Exercise Performance and Blood Storage Condition and Storage Time in Autologous Blood Doping

biology Review Relation between Exercise Performance and Blood Storage Condition and Storage Time in Autologous Blood Doping Benedikt Seeger and Marijke Grau * Molecular and Cellular Sports Medicine, German Sport University Cologne, 50677 Cologne, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-221-4982-6116 Simple Summary: Autologous blood doping (ABD) refers to sampling, storage, and re-infusion of one’s own blood to improve circulating red blood cell (RBC) mass and thus the oxygen transport and finally the performance capacity. This illegal technique employed by some athletes is still difficult to detect. Hence knowledge of the main effects of ABD is needed to develop valid detection methods. Performance enhancement related to ABD seems to be well documented in the literature, but applied study designs might affect the outcome that was analyzed herein. The majority of recent studies investigated the effect of cold blood storage at 4 ◦C, and only few studies focused on cryopreservation, although it might be suspected that cryopreservation is above all applied in sport. The storage duration—the time between blood sampling and re-infusion—varied in the reported literature. In most studies, storage duration might be too short to fully restore the RBC mass. It is thus concluded that most reported studies did not display common practice and that the reported performance outcome might be affected by these two variables. Thus, knowledge of the real effects of ABD, as applied in sport, on performance and associated parameters are needed to develop reliable detection techniques. Abstract: Professional athletes are expected to continuously improve their performance, and some might also use illegal methods—e.g., autologous blood doping (ABD)—to achieve improvements. -

Fcy^N RESPONDENTS 37 SCA 001960

Le Tour 2005 Tech Features Road MTB BMX Cyciocross Track News Photos Recent News January 2005 February 2005 Latest Cycling News for August 24, 2005 March 2005 April 2005 Edited by Jeff Jones May 2005 June 2005 July 2005 EPO test under scrutiny August 2005 September 2005 October 2005 Latest Armstrong case makes big waves November 2005 Recently on December 2005 Cyclingnewi 2004 & earlier By Jeff Jones The stunning news reported by L'Equipe yesterday that Lance Armstrong allegedly used EPO during the 1999 Tour de France has sparked a huge debate in the cycling world. Using research data obtained from the French Laboratoire national de depistage du dopage de Chatenay-Malabry (LNDD), L'Equipe journalists pieced together evidence over several months that linked six "positive" EPO samples to Lance Armstrong, before publishing it in South China Sec Tuesday's edition of the widely read French paper. If the results are correct, then the Photo: © Charlie Is: ramifications for Armstrong could be great, even though he officially retired from the sport 2QPJ5 after winning his seventh Tour last month. Roa,d_CaJenc It's an unprecedented case in cycling, and quite possibly in any sport: that an athlete has Thursday, Jam been accused of doping on the basis of scientific research results. Usually, the subjects of a study are kept anonymous - and indeed they were by the lab - although the news did Jayco Bay Cycl manage to leak. When the urinary EPO test was fkst developed by the LNDD in 2000. urine Classic, Aus Nl samples from the infamous 1998 Tour de France were used, as it was believed they were likely to contain EPO. -

WW1 CV for Randal S Gaulke Version November 2017

Curriculum Vitae Randal S. Gaulke Battlefield Tour Guide, Historian and Re-enactor 2017 Sabbatical in Doulcon, France • From 15 May to 15 November, 2017, Randal lived and worked as a Freelance tour guide to the American battlefields of WW1. • During this period he led numerous small-group tours; typically showing family members where their grandparents or parents fought. • He also participated in the filming of “A Golden Cross to Bear” (33rd Division, AEF) being produced by filmmaker Kane Farabaugh. o Viewing on various PBS stations in Illinois is planned for Memorial Day 2018. Previous Battlefield Tour Summary • Randal has visited the Western Front more than twenty times between 1986 and 2016. • Much of that time has been spent studying the Meuse-Argonne and St. Mihiel sectors. • Key tour summaries are listed below: --Verdun and Inf. Regt. Nr. 87 Tour, 2013 Randal spent three days leading an individual to the sites where his (German) great uncle fought, including the Verdun battlefield. --Western Front Association, USA Branch, 2007 Battlefield Tour Randal led the second half of the tour; focusing on the Meuse-Argonne and St. Mihiel Sectors. --8th Kuerassier (Reenacting) Regiment Trip to Germany and the Western Front, 2005 This was a five-day tour that followed in the regiment’s footsteps. --Verdun 1999 Tour Randal led participants on a two-day tour of the Verdun 1916 battlefield. --First Western Front Association, USA Branch, Battlefield Tour, 1998 The tour was organized by Tony and Teddy Noyes of UK-based Flanders Tours. Randal and Stephen Matthews provided significant input, US-based marketing, and logistical support to the effort. -

Armstrong.Pdf

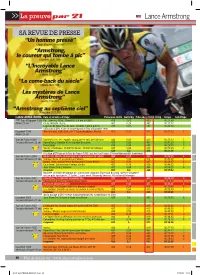

>> La preuve par 21 Lance Armstrong SA REVUE DE PRESSE “Un homme pressé” L’Equipe Magazine, 04.09.1993 “Armstrong, le coureur qui tombe à pic” L’Humanité, 05.07.1999 “L’Incroyable Lance Armstrong” L’Equipe, 12.07.1999 “Le come-back du siècle” L’Equipe, 26.07.1999 “Les mystères de Lance Armstrong” Le JDD, 27.06.2004 “Armstrong au septième ciel” Le Midi Libre, 25.07.2005 Lance ARMSTRONG Cols et victoires d’étape Puissance réelle watts/kg Puissance étalon 78 kg temps Cols Etape Tour Tour d’Espagne 1998 Pal. Jimenez 433w, 20min30s, 8,4 km à 6,49%, 418 5,65 400 00:21:49 4ème-27 ans Cerler. Montée courte. 462 6,24 442 00:11:33 Lagunas de Neila. Peu de vent, en forêt, 7 km à 8,57%, 415 5,61 397 00:22:18 Utilisation d’EPO et de cortisone durant le Tour d’Espagne 1998 Dauphiné 1999 Mont Ventoux CLM. ‘Battu de 1’1s par Vaughters. Record. 455 6,15 432 00:57:52 1 8ème-28 ans Tour de France 2004 La Mongie. 2ème derrière Basso 487 6,58 462 00:23:15 2 Tour de France 1999 Sestrières 1er. 1er «exploit» marquant en solo. Vent de face 448 6,05 420 00:27:13 5 1er puis déclassé-33 ans Beille 1er. En solitaire. 438 5,92 416 00:45:40 6 1er puis déclassé-28 ans Alpe d’Huez. Contrôle et se contente de suivre. 436 5,89 407 00:41:20 3 Chalimont 1er. Victoire à Villard de Lans 410 5,54 392 00:19:05 3 Piau Engaly 395 5,34 385 00:26:15 5 Alpe d’Huez CLM 1er. -

A Legal Analysis of the WADA-Code Beyond the Contador Case

A legal analysis of the WADA-code beyond the Contador case Faculty: Tilburg Law School Department: Social Law and Social Politics Master: International and European Labour Law Author: Lonneke Zandberg Student number: 537776 Graduation date: March 14, 2012 Exam Committee: Prof. dr. M. Colucci Prof. dr. F.H.R. Hendrickx Table of contents: LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 5 1. HISTORY OF ANTI-DOPING .................................................................................................... 7 2. WADA .................................................................................................................................. 8 2.1 The arise of WADA .............................................................................................................. 8 2.2 World Anti Doping Code 2009 (WADA-code) ..................................................................... 8 2.3 The binding nature of the WADA-code ............................................................................. 10 2.4 Compliance and monitoring of the WADA-code .............................................................. 11 2.5 Sanctions for athletes after violating the WADA-code ..................................................... 12 3. HOW TO DEAL WITH A POSITIVE DOPING RESULT AFTER AN ATHLETE HAS EATEN CONTAMINATED -

Lance Armstrong Has Something to Get Off His Chest

Texas Monthly July 2001: Lanr^ Armstrong Has Something to . Page 1 of 17 This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. For public distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, contact [email protected] for reprint information and fees. (EJiiPfflNITHIS Lance Armstrong Has Something to Get Off His Chest He doesn't use performance-enhancing drugs, he insists, no matter what his critics in the European press and elsewhere say. And yet the accusations keep coming. How much scrutiny can the two-time Tour de France winner stand? by Michael Hall In May of last year, Lance Armstrong was riding in the Pyrenees, preparing for the upcoming Tour de France. He had just completed the seven-and-a-half-mile ride up Hautacam, a treacherous mountain that rises 4,978 feet above the French countryside. It was 36 degrees and raining, and his team's director, Johan Bruyneel, was waiting with a jacket and a ride back to the training camp. But Lance wasn't ready to go. "It was one of those moments in my life I'll never forget," he told me. "Just the two of us. I said, 'You know what, I don't think I got it. I don't understand it.1 Johan said, 'What do you mean? Of course you got it. Let's go.' I said, 'No, I'm gonna ride all the way down, and I'm gonna do it again.' He was speechless. And I did it again." Lance got it; he understood Hautacam—in a way that would soon become very clear. -

Doping Critics Hack Computers for Chris Froome Data

Doping Critics Hack Computers For Chris Froome Data Team Sky boss Sir Dave Brailsford has revealed that critics of Team Sky have hacked into the performance data of Tour de France leader Chris Froome. Sir Dave Brailsford said he believes data has been stolen by team©s critics to discredit the performances of Froome and raise doping suggestions. The Team principal added we think someone has hacked into our training data and got Chris' files, so we've got some legal guys on the case there. On Monday evening, a video that purportedly showed the ride of Froome on Mont Ventoux during the 2013 Tour with data on speed, heart rate, power, and cadence overlaid was removed from YouTube. Viewers of the video took to social media for interpreting the data and many suggested that there was evidence of doping. Froome had previously expressed his frustration ahead of the Tour of "clowns" trying to interpret power data. Chris Froome was leading the 2015 Tour de France by 12 seconds on the first rest day in Pau. Froome recently produced a ride to conquer stage 10 of the Tour de France and increase his overall lead to nearly three minutes. Froome - who led by 12 seconds overnight - broke away with 6.4km left of the first summit finish of the 2015 Tour de France to win in La Pierre-Saint-Martin. BBC Sport©s Matt Slater remarked this was a devastating win for Froome and Team Sky, with Grand Tour champions and challengers scattered all over the road up to La Pierre-Saint-Martin. -

Case Study: the Tour De France & Vsquared TV

Case Study: Broadcast TV The Tour de France & Vsquared TV Solution Summary PROMISE and Vsquared TV Create At a Glance • Vsquared TV is an independent The Fastest, Most Advanced Editing production company which specializes in covering cycling Suite for the Tour de France • Vsquared TV was switching to Final Cut Pro X for the 2014 Tour de France broadcasts and needed to upgrade their edit suites • With the help of PROMISE, Vsquared TV built 4 of the most advanced edit suites for sporting events The Solution • Vsquared TV relied on the PROMISE Pegasus2 R6/M4 Thunderbolt 2 storage and the PROMISE SANLink2 Benefits • Faster access to archive footage • Increased speed in editing - no more waits for rendering The Tour de France & Vsquared TV The Tour de France is the most prestigious cycling event and one of the most famous • Huge gains in efficiency were sporting events in the world. The top cyclists from around the world compete in a grueling crucial since this gave Vsquared three week 3,500 km journey each July that takes competitors through the mountain extra time to polish the final edits chains of the Pyrenees and the Alps and on to the finish on the Champs-Élysées in Paris. and still make air The Tour de France is broadcast worldwide on 121 different television channels in over • SANLink2 was vital to the process 190 countries with huge audiences watching each stage, including a record 44 million since the Mac Pro required a viewers who took in one of the final stages in the 2009 race. -

Chris Froome Exclusive Ready to Join the Greats of Cycling Highs and Lows of Legal Doping

The thrill of the ride MAGAZINE OF THE YEAR Glory of the Giro Italy’s most stunning ride Chris Froome exclusive Ready to join the greats of cycling Highs and lows of legal doping ISSUE 48 ] JUNE 2016 ] £5.50 Frame artistry with Independent Fabrication Alpe d’Huez by the undiscovered route The thrill of the ride JUNE 2016 COLLECTORS’ EDITION 048 Italy Mountains of the The Dolomites’ sculpted peaks will host the 30th anniversary of the Maratona sportive and a breathtaking stage of the Giro d’Italia this summer. Cyclist clips in to discover the history and legendsmind of the ‘Pale Mountains’ Words MARK BAILEY Photography JUAN TRUJILLO ANDRADES CYCLIST 61 Italy he Dolomites are mountains of magic and miracles, where local folklore transforms jagged peaks into the turreted castles of mythical kings, glistening lakes become bewitched pools of dazzling treasure, and howling snowstorms evoke the spittle and fury of ancient spirits. As I cycle up the 2,239m Passo Pordoi, a lofty pass through this spellbinding region known as the ‘Monti Pallidi’ (Pale Mountains), stories surround me. Legend says the silvery rock spires ahead, Heading out of the village of Corvara at which glow gold, pink and purple at dawn, were painted the start of the ride, by a magical gnome to entice a star-dwelling princess back already the scenery is to her earthbound prince. The white edelweiss flowers in nudging close to epic the meadows are her gifts from the moon. Even cycling Heritage site in north-eastern Italy full of geological fans become entranced here. -

2013 Tour De France Yellow Jersey Winner

2013 TOUR DE FRANCE YELLOW JERSEY WINNER CHRIS FROOME APPOINTED TURBINE AMBASSADOR KEY HIGHLIGHTS: ● 2013 Tour de France winner Chris Froome joins Rhinomed as Turbine™ Global Ambassador ● New Turbine™ developed off the back of feedback from Froome ● Froome using Turbine™ during the 2015 Tour de France ● Murdoch University (WA) currently undertaking confirmation trial on Turbine™ performance and recovery utility 6th July, 2015. Melbourne, Australia. Rhinomed Ltd (ASX:RNO) an Australian company focused on the development of novel nasal and respiratory technology today announced 2013 Tour de France Yellow Jersey winner Chris Froome has joined as its new Turbine™ Global Ambassador. Froome, one of the world's leading and most popular cyclists, won the Tour de France in 2013 and has also won the Tour of Oman, the Tour de Romandie, came second in the Vuelta a Espana, and won Bronze in the 2012 Olympic Games Time Trial. Froome was also Velo Magazine International Cyclist of the Year: 2013. He is one of the hot favourites in this year’s Tour de France. Froome, who wore the Turbine during the first Stage of this years Tour commented: "It’s a great piece of equipment. Less energy and distraction with breathing means I can use more energy in other important parts of my riding, like focussing on power, cadence and keeping my head in the game." Rhinomed CEO Michael Johnson said: “We met Chris when he started wearing the Turbine™ in last years Vuelta a Espana, and have been building a strong relationship since that time. Chris provided extensive input and data into the new Turbine™ design and we are thrilled to have now locked in this long-term relationship.” Murdoch University in Western Australia are currently undertaking a confirmation trial on the new Turbine™.