Supplementary Information on the Regulatory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan Abstract In Singapore, the percentage of elected female politicians rose from 3.8 percent in 1984 to 22.5 percent after the 2015 general election. After years of exclusion, why were gender reforms adopted and how did they lead to more women in political office? Unlike South Korea and Taiwan, this paper shows that in Singapore party pragmatism rather than international diffusion of gender equality norms, feminist lobbying, or rival party pressures drove gender reforms. It is argued that the ruling People’s Action Party’s (PAP) strategic and electoral calculations to maintain hegemonic rule drove its policy u-turn to nominate an average of about 17.6 percent female candidates in the last three elections. Similar to the PAP’s bid to capture women voters in the 1959 elections, it had to alter its patriarchal, conservative image to appeal to the younger, progressive electorate in the 2000s. Additionally, Singapore’s electoral system that includes multi-member constituencies based on plurality party bloc vote rule also makes it easier to include women and diversify the party slate. But despite the strategic and electoral incentives, a gender gap remains. Drawing from a range of public opinion data, this paper explains why traditional gender stereotypes, biased social norms, and unequal family responsibilities may hold women back from full political participation. Keywords: gender reforms, party pragmatism, plurality party bloc vote, multi-member constituencies, ethnic quotas, PAP, Singapore DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5509/2016892369 ____________________ Netina Tan is an assistant professor of political science at McMaster University. -

Singapore's Chinese-Speaking and Their Perspectives on Merger

Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies, Volume 5, 2011-12 南方華裔研究雜志, 第五卷, 2011-12 “Flesh and Bone Reunite as One Body”: Singapore’s Chinese- speaking and their Perspectives on Merger ©2012 Thum Ping Tjin* Abstract Singapore’s Chinese speakers played the determining role in Singapore’s merger with the Federation. Yet the historiography is silent on their perspectives, values, and assumptions. Using contemporary Chinese- language sources, this article argues that in approaching merger, the Chinese were chiefly concerned with livelihoods, education, and citizenship rights; saw themselves as deserving of an equal place in Malaya; conceived of a new, distinctive, multiethnic Malayan identity; and rejected communist ideology. Meanwhile, the leaders of UMNO were intent on preserving their electoral dominance and the special position of Malays in the Federation. Finally, the leaders of the PAP were desperate to retain power and needed the Federation to remove their political opponents. The interaction of these three factors explains the shape, structure, and timing of merger. This article also sheds light on the ambiguity inherent in the transfer of power and the difficulties of national identity formation in a multiethnic state. Keywords: Chinese-language politics in Singapore; History of Malaya; the merger of Singapore and the Federation of Malaya; Decolonisation Introduction Singapore’s merger with the Federation of Malaya is one of the most pivotal events in the country’s history. This process was determined by the ballot box – two general elections, two by-elections, and a referendum on merger in four years. The centrality of the vote to this process meant that Singapore’s Chinese-speaking1 residents, as the vast majority of the colony’s residents, played the determining role. -

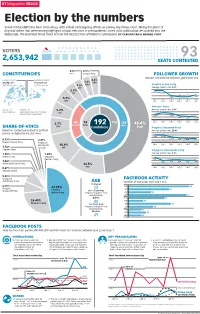

200708 BT Ge2020 in Numbers

BT Infographics GE2020 Election by the numbers Social media platforms have been abuzz with virtual campaigning efforts as polling day draws close, taking the place of physical rallies that were among highlights of past elections in pre-pandemic times. With political parties pushed into the digital age, The Business Times looks at how the GE2020 has unfolded in cyberspace. BY CLAUDIA TAN & NATALIE CHOY VOTERS 93 2,653,942 SEATS CONTESTED 0.5% 0.5% CONSTITUENCIES PPP Independent FOLLOWER GROWTH Number of Facebook followers gained per day Largest GRC Smallest SMC 2.6% Ang Mo Kio Potong Pasir 2.6% SDA 185,465 electors 19,740 electors 2.6% RDU People’s Action Party SPP Average growth rate: 2.3% 3.1% 1,332 RP 1,347 338 338 653 5.2% 516 NSP July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 Workers’ Party GRCs: 17 SMCs: 14 5.2% Average growth rate: 9.5% New: Sengkang New: Kebun Baru, Yio Chu Kang, PV Marymount, Punggol West 2,699 2,098 2,421 1,474 1,271 1,336 July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 5.7% 40 74 118 152 48.4% Female New 192PSP Male SHARE-OF-VOICE SDP Candidates PAP Progress Singapore Party Based on content generated by political Average growth rate: 22.4% parties on digital media platforms 1,539 1,539 1,119 0.19% 2.29% 932 836 776 People’s Power Party Singapore Democratic 10.9% July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 1.72% Alliance WP Peoples Voice Singapore Democratic Party 1.48% 1.60% Average growth rate: 5.6% Reform Party Singapore People’s Party 813 1.46% 498 558 565 503 540 National Solidarity Party 12.5% 0.67% PSP July 1 July 2 -

Major Vote Swing

BT INFOGRAPHICS GE2015 Major vote swing Bukit Batok Sengkang West SMC SMC Sembawang Punggol East GRC SMC Hougang SMC Marsiling- Nee Soon Yew Tee GRC GRC Chua Chu Kang Ang Mo Kio Holland- GRC GRC Pasir Ris- Bukit Punggol GRC Hong Kah Timah North SMC GRC Aljunied Tampines Bishan- GRC GRC Toa Payoh East Coast GRC GRC West Coast Marine GRC Parade Tanjong Pagar GRC GRC Fengshan SMC MacPherson SMC Mountbatten SMC FOUR-MEMBER GRC Jurong GRC Potong Pasir SMC Chua Chu Kang Registered voters: 119,931; Pioneer Yuhua Bukit Panjang Radin Mas Jalan Besar total votes cast: 110,191; rejected votes: 2,949 SMC SMC SMC SMC SMC 76.89% 23.11% (84,731 votes) (25,460 votes) PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY (83 SEATS) WORKERS’ PARTY (6 SEATS) PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY POWER PARTY Gan Kim Yong Goh Meng Seng Low Yen Ling Lee Tze Shih SIX-MEMBER GRC Yee Chia Hsing Low Wai Choo Zaqy Mohamad Syafarin Sarif Ang Mo Kio Pasir Ris-Punggol 2011 winner: People’s Action Party (61.20%) Registered voters: 187,771; Registered voters: 187,396; total votes cast: 171,826; rejected votes: 4,887 total votes cast: 171,529; rejected votes: 5,310 East Coast Registered voters: 99,118; 78.63% 21.37% 72.89% 27.11% total votes cast: 90,528; rejected votes: 1,008 (135,115 votes) (36,711 votes) (125,021 votes) (46,508 votes) 60.73% 39.27% (54,981 votes) (35,547 votes) PEOPLE’S THE REFORM PEOPLE’S SINGAPORE ACTION PARTY PARTY ACTION PARTY DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE Ang Hin Kee Gilbert Goh J Puthucheary Abu Mohamed PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ Darryl David Jesse Loo Ng Chee Meng Arthero Lim ACTION PARTY PARTY Gan -

Redalyc.Jamaica: Forty Years of Independence

Revista Mexicana del Caribe ISSN: 1405-2962 [email protected] Universidad de Quintana Roo México Mcnish, Vilma Jamaica: Forty years of independence Revista Mexicana del Caribe, vol. VII, núm. 13, 2002, pp. 181-210 Universidad de Quintana Roo Chetumal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=12801307 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 190/VILMAMCNISH INTRODUCTION ortyyearsagoonAugust6,1962Jamaicabecamean F independentandsovereignnationaftermorethan300 hundredyearsofcolonialismundertheBritishEmpire.Inthein- ternationalcontext,Jamaicaisarelativelyyoungcountry.Indeed, incontrasttothecountriesinLatinAmerica,Jamaicaandthe othercountriesoftheEnglish-speakingCaribbean,allformercolo- niesofGreatBritain,onlybecameindependentinthesecondhalf ofthe20thcentury.UnliketheirSpanish-speakingneighboursthere- fore,noneoftheseterritorieshadthedistinctionofbeingfound- ingmembersofeithertheUnitedNationsorthehemispheric bodytheOrganisationofAmericanStates. Thepurposeofmypresentationistopresentanoverview,a perspectiveofthepolitical,economicandculturaldevelopment ofJamaicaoverthesefortyyears.Butbeforedoingso,Ithinkit isimportanttoprovideahistoricalcontexttomodernJamaica. SoIwillstartwithabriefhistoryofJamaica,tracingthetrajec- toryofconquest,settlementandcolonisationtoemancipation, independenceandnationhood. -

One Party Dominance Survival: the Case of Singapore and Taiwan

One Party Dominance Survival: The Case of Singapore and Taiwan DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lan Hu Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor R. William Liddle Professor Jeremy Wallace Professor Marcus Kurtz Copyrighted by Lan Hu 2011 Abstract Can a one-party-dominant authoritarian regime survive in a modernized society? Why is it that some survive while others fail? Singapore and Taiwan provide comparable cases to partially explain this puzzle. Both countries share many similar cultural and developmental backgrounds. One-party dominance in Taiwan failed in the 1980s when Taiwan became modern. But in Singapore, the one-party regime survived the opposition’s challenges in the 1960s and has remained stable since then. There are few comparative studies of these two countries. Through empirical studies of the two cases, I conclude that regime structure, i.e., clientelistic versus professional structure, affects the chances of authoritarian survival after the society becomes modern. This conclusion is derived from a two-country comparative study. Further research is necessary to test if the same conclusion can be applied to other cases. This research contributes to the understanding of one-party-dominant regimes in modernizing societies. ii Dedication Dedicated to the Lord, Jesus Christ. “Counsel and sound judgment are mine; I have insight, I have power. By Me kings reign and rulers issue decrees that are just; by Me princes govern, and nobles—all who rule on earth.” Proverbs 8:14-16 iii Acknowledgments I thank my committee members Professor R. -

Beyond Factionalism to Unity: Labour Under Starmer

Beyond factionalism to unity: Labour under Starmer Article (Accepted Version) Martell, Luke (2020) Beyond factionalism to unity: Labour under Starmer. Renewal: A journal of social democracy, 28 (4). pp. 67-75. ISSN 0968-252X This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/95933/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Beyond Factionalism to Unity: Labour under Starmer Luke Martell Accepted version. Final article published in Renewal 28, 4, 2020. The Labour leader has so far pursued a deliberately ambiguous approach to both party management and policy formation. -

Hauraki-Waikato

Hauraki-Waikato Published by the Parliamentary Library July 2009 Table of Contents Hauraki-Waikato: Electoral Profile......................................................................................................................3 2008 Election Results (Electorate) .................................................................................................................4 2008 Election Results - Party Vote .................................................................................................................4 2005 Election Results (Electorate) .................................................................................................................5 2005 Election Results - Party Vote .................................................................................................................5 Voter Enrolment and Turnout 2005, 2008 .......................................................................................................6 Hauraki-Waikato: People ...................................................................................................................................7 Population Summary......................................................................................................................................7 Age Groups of the Māori Descent Population .................................................................................................7 Ethnic Groups of the Māori Descent Population..............................................................................................7 -

JD-Acting-General-Secretary-Wales

Labour Party Job Description Job title: Acting General Secretary – Wales Responsible for: All staff employed by the Labour Party in Wales Location: The post holder will be based at the Welsh Labour HQ in Cardiff Key Purpose: The General Secretary – Welsh Labour is responsible for the effective and efficient organisation of Welsh Labour. The General Secretary will build the organisational capacity necessary to maximise Labour representation at all levels of government. Specific Responsibilities: Working to implement the Welsh Labour Organisational strategy, including strategies for the promotion of membership recruitment, campaigning activity, media communications and the selection of candidates. Co-ordinating the work of AMs/MPs/MEPs/ and representatives of the Welsh Local Authorities to maximise support for Labour’s policy programme. Under the political leadership of the Welsh Labour Leader and working with all other stakeholders to ensure the effective promotion of, and campaigning for the Welsh Labour Government and Labour’s Shadow Cabinet in Wales. Maintaining relationships with Leaders of Labour Groups in Local Authorities in Wales to ensure the effective promotion of and campaigning for Welsh Labour policies in local government. The co-ordination and production of all Welsh policy documents, manifestos and research briefings, ensuring they promote Welsh Labour’s policy programme in government in Wales and as the official Opposition in Westminster. Co-ordination of effective communications between Welsh Labour and elected representatives and individual members. Day-to-day management of all Labour Party staff in Wales. Act where appropriate, as Media Spokesperson on organisational matters for Welsh Labour. Financial management including drawing up maintaining and controlling budgets. -

Clement Attlee Was Born on 3 January 1883 in Putney, the Seventh of Eight Children

P R O F I L E Clement Attlee was born on 3 January 1883 in Putney, the seventh of eight children. His father, Henry Attlee, was a solicitor and senior partner in the firm of Druces and Attlee, whose offices were in the Middle Temple. After being home-schooled, Attlee was educated at the preparatory school Northaw Place and then Haileybury College, both in Hertfordshire. At Haileybury, which had a strong military ethos, Attlee became an enthusiastic member of the Volunteer Rifle Corps. After leaving Haileybury in 1901 Attlee went on to University College, Oxford, where he studied Modern History. He specialised in Italian and Renaissance history and graduated in 1904 with a second-class degree. After leaving Oxford Attlee followed in his father’s footsteps and entered the legal profession, although without any great enthusiasm for it. He had been admitted to the Inner Temple on 30 January 1904, and in the autumn of that year entered the Lincoln’s Inn chambers of Sir Philip Gregory. His father’s connections meant he had already C L E M E N T dined at the Inner Temple; he was called to the Bar in March 1906. In October 1905, Attlee accompanied his brother Laurence to the A T T L E E Haileybury Club, a club in Stepney, East London for working-class boys, run by former Haileybury College pupils. It was connected to B O R N 1 8 8 3 the Territorial Army, and volunteers were expected to become non- D I E D 1 9 6 7 commissioned officers. -

Friend Or Ally? a Question for New Zealand

.......... , ---~ MeN AIR PAPERS NUMBER T\\ ELVE FRIEND OR ALLY? A QUESTION FOR NEW ZEALAND By EWAN JAMIESON THE INSTI FUTE FOR NATIONAL SI'R-~TEGIC STUDIES ! I :. ' 71. " " :~..? ~i ~ '" ,.Y:: ;,i:,.i:".. :..,-~.~......... ,,i-:i:~: .~,.:iI- " yT.. -.~ .. ' , " : , , ~'~." ~ ,?/ .... ',~.'.'.~ ..~'. ~. ~ ,. " ~:S~(::!?- ~,i~ '. ? ~ .5" .~.: -~:!~ ~:,:i.. :.~ ".: :~" ;: ~:~"~',~ ~" '" i .'.i::.. , i ::: .',~ :: .... ,- " . ".:' i:!i"~;~ :~;:'! .,"L': ;..~'~ ',.,~'i:..~,~'"~,~: ;":,:.;;, ','" ;.: i',: ''~ .~,,- ~.:.~i ~ . '~'">.'.. :: "" ,-'. ~:.." ;';, :.~';';-;~.,.";'."" .7 ,'~'!~':"~ '?'""" "~ ': " '.-."i.:2: i!;,'i ,~.~,~I~out ;popular: ~fo.rmatwn~ .o~~'t,he~,,:. "~.. " ,m/e..a~ tg:,the~6w.erw!~chi~no.wtetl~e.~gi..~e~ ;~i:~.::! ~ :: :~...i.. 5~', '+~ :: ..., .,. "'" .... " ",'.. : ~'. ,;. ". ~.~.~'.:~.'-? "-'< :! :.'~ : :,. '~ ', ;'~ : :~;.':':/.:- "i ; - :~:~!II::::,:IL:.~JmaiegMad}~)~:ib;:, ,?T,-. B~;'...-::', .:., ,.:~ .~ 'z • ,. :~.'..." , ,~,:, "~, v : ", :, -:.-'": ., ,5 ~..:. :~i,~' ',: ""... - )" . ,;'~'.i "/:~'-!"'-.i' z ~ ".. "', " 51"c, ' ~. ;'~.'.i:.-. ::,,;~:',... ~. " • " ' '. ' ".' ,This :iis .aipul~ ~'i~gtin~e ..fdi;:Na~i~real..Sfi'~te~ie.'Studi'~ ~It ;is, :not.i! -, - .... +~l~ase,~ad.~ p,g, ,,.- .~, . • ,,. .... .;. ...~,. ...... ,._ ,,. .~ .... ~;-, :'-. ,,~7 ~ ' .~.: .... .,~,~.:U7 ,L,: :.~: .! ~ :..!:.i.i.:~i :. : ':'::: : ',,-..-'i? -~ .i~ .;,.~.,;: ~v~i- ;. ~, ~;. ' ~ ,::~%~.:~.. : ..., .... .... -, ........ ....... 1'-.~ ~:-~...%, ;, .i-,i; .:.~,:- . eommenaati6'r~:~xpregseff:or ;ii~iplie'd.:;~ifl~in.:iat~ -:: -

The British Labour Party and the Reform of the House of Lords, 1918 to Date

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1960 The rB itish Labour Party and the reform of the House of Lords, 1918 to date. Yousan Wang University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Wang, Yousan, "The rB itish Labour Party and the reform of the House of Lords, 1918 to date." (1960). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2557. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2557 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BRUiSH LABOUR PART/ THE REFORM OF THE HOUSE OF LORDS, 1918 TO DATE YU SAN WANG 1960 THE BRITISH LABOUR PARTY AND THE REPOEM OF THE HOUSE OP LORDS, I9I8 TO DATE Yu San Wang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Massachusetts Amherst August , i960 TABLE OP CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II, A BRIEF HISTORY OP EFFORTS WITHIN THE LABOUR PARTY TO REFORM THE HOUSE OP LORDS, 1918 TO dak: 8 III. THE REFORM OF THE POWERS OF THE HOUSE OF LORDS 30 IV, PROPOSALS FOR MINOR MODIFICATIONS OP THE COMPOSITION OP THE HOUSE OP LORDS , , , , 46 V, PROPOSALS FOR THE WHOLESALE RECONSTRUCTION OP THE HOUSE OP LORDS 62 VI, PROPOSALS FOE THE ABOLITION OF THE HOUSE OP LORDS 71 VII, CONCLUSION AND PROSPECTS FOR THE FUTURE .