Lambert, Mary Grace (Meg) (2019) Inherited Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Round 3 Bowl Round 3 First Quarter

NHBB A-Set Bowl 2016-2017 Bowl Round 3 Bowl Round 3 First Quarter (1) This author of Postcards from the Edge wrote multiple autobiographical works that openly discuss her positive experience with electroconvulsive therapy as treatment for bipolar disorder. This author of the memoir The Princess Diarist is, with her mother, the subject of Bright Lights, a documentary that premiered on HBO in January 2017, just weeks after their deaths. For ten points, name this mental health advocate, daughter of Debbie Reynolds, and actress who portrayed Princess Leia in the Star Wars films. ANSWER: Carrie Fisher (2) Oscar L´opez Rivera, an independence activist for this territory, had his prison sentence commuted during Barack Obama's last week in office. In 2016, this territory was blocked from declaring bankruptcy by the Supreme Court. Like Guam and the Philippines, this commonwealth's ownership transferred to the U.S. after the Spanish-American War. For ten points, name this Caribbean island territory where activists in its capital, San Juan, wish to become the 51st U.S. state. ANSWER: Puerto Rico (3) These people discovered a \land of stone slabs" that might be the Torngat Mountains. These people harvested lumber from Markland and recorded finding grapes in another area. These people battled against Skraelings and found grapes during their brief settlements in Vinland and at L'Anse Aux Meadows. The first European peoples to land in Canada were, for ten points, what Scandinavians, including the explorer Leif Ericsson? ANSWER: Norsemen (or Vikings; accept Danes or Greenlanders; prompt on Scandinavians before mentioned) (4) This group regularly held meetings at the Menger Hotel Bar of San Antonio. -

The Dawn of American Cryptology, 1900–1917

United States Cryptologic History The Dawn of American Cryptology, 1900–1917 Special Series | Volume 7 Center for Cryptologic History David Hatch is technical director of the Center for Cryptologic History (CCH) and is also the NSA Historian. He has worked in the CCH since 1990. From October 1988 to February 1990, he was a legislative staff officer in the NSA Legislative Affairs Office. Previously, he served as a Congressional Fellow. He earned a B.A. degree in East Asian languages and literature and an M.A. in East Asian studies, both from Indiana University at Bloomington. Dr. Hatch holds a Ph.D. in international relations from American University. This publication presents a historical perspective for informational and educational purposes, is the result of independent research, and does not necessarily reflect a position of NSA/CSS or any other US government entity. This publication is distributed free by the National Security Agency. If you would like additional copies, please email [email protected] or write to: Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Suite 6886 Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755 Cover: Before and during World War I, the United States Army maintained intercept sites along the Mexican border to monitor the Mexican Revolution. Many of the intercept sites consisted of radio-mounted trucks, known as Radio Tractor Units (RTUs). Here, the staff of RTU 33, commanded by Lieutenant Main, on left, pose for a photograph on the US-Mexican border (n.d.). United States Cryptologic History Special Series | Volume 7 The Dawn of American Cryptology, 1900–1917 David A. -

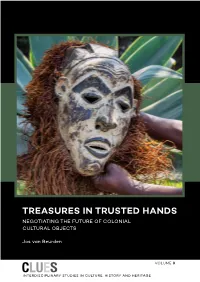

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. -

IHBB Asia Bowl Round 3 – Middle School

IHBB Asian Championships Bowl 2016-2017 Bowl Round 3 Bowl Round 3 – Middle School First Quarter (1) This country’s government published the 1995 report “Bringing Them Home”, detailing a genocidal 20th century campaign to remove native children from their homes. Though reconciliation efforts of the “Stolen Generations” included “National Sorry Day” in 1998, it wasn’t until John Howard was succeeded by Kevin Rudd that this country’s Prime Minister apologized. For ten points, name this country where hundreds of thousands of Aboriginal children were kidnapped by a government based in Canberra. ANSWER: Australia (2) This man rose to prominence as a subordinate of John Jervis (JAR-vis) at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent. This man’s forces intercepted Pierre-Charles Villeneuve after they left Cadiz. This man, who lost an arm while leading an attack on Copenhagen, ordered that the message “England expects that every man will do his duty” be sent aboard his flagship, the HMS Victory. For ten points, name this British admiral who won the Battle of Trafalgar. ANSWER: Horatio Nelson (3) These people discovered a “land of stone slabs” that might be the Torngat Mountains. These people harvested lumber from Markland and recorded finding grapes in another area. These people battled against Skraelings and found grapes during their brief settlements in Vinland and at L’Anse Aux Meadows. The first European peoples to land in Canada were, for ten points, what Scandinavians, including the explorer Leif Ericsson? ANSWER: Norsemen (or Vikings; accept Danes or Greenlanders; prompt on Scandinavians before mentioned) (4) A portrait of a man from this city shows him holding his chin in one hand and a teapot he is working on in another. -

The Mongolian Naval Expedition to Java in the 13Th Century

OF PALM WINE, WOMEN AND WAR The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) was established as an autonomous organization in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are the Regional Economic Studies (RES, including ASEAN and APEC), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 00 PalmWineWomen.indd 2 7/30/13 11:32:36 AM OF PALM WINE, WOMEN AND WAR The Mongolian Naval Expedition to Java in the 13th Century DAVID BADE INSTITUTE OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES Singapore First published in Singapore in 2013 by ISEAS Publishing Institute of Southeast Asian Studies 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Pasir Panjang Singapore 119614 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. © 2002 David W. Bade The responsibility for facts and opinions in this publication rests exclusively with the author and his interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views or the policy of the Institute or its supports. -

WORLD WAR ONE This Subject Guide Lists Documents in the Eisenhower

WORLD WAR ONE This subject guide lists documents in the Eisenhower Presidential Library related to World War I. Although the United States did not enter the war until April 6, 1917, some documents on this list relate to the war in Europe prior to that date. Post-war documents related to WWI veterans with no actual information about the war are not included. These collections primarily document the experiences of young men and women at the start of their adult lives. If you have any questions about specific collections, please refer to the finding aid to that collection for more information. Chronology of First World War (with an emphasis on US involvement) 1914 June 28 Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, assassinated by Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip while the couple were visiting Sarajevo. July 28 Austria-Hungary declares war on Serbia. August 1 Germany declares war on Russia. August 3 Germany declares war on France. August 4 United Kingdom declares war on Germany, after Germany invades Belgium. August 6 Austria-Hungary declares war on Russia and Serbia declares war on Germany. August 26 Battle of Tannenberg begins. August 19 U.S. President Woodrow Wilson announces the U.S. will remain neutral. September 5 First Battle of the Marne and the beginning of trench warfare. October 19 Battle of Ypres begins. November 3 United Kingdom announces that the North Sea is a military area, effectively creating a blockade of goods into Germany. December 24 Unofficial Christmas truce is declared. 1915 February 4 Germany declares a "war zone" around Great Britain, effecting a submarine blockade where even neutral merchant vessels were to be potential targets. -

Freek Colombijn, Hisao Furukawa, Coastal Wetlands of Indonesia; Environment, Subsistence and Exploitation

Book Reviews - Freek Colombijn, Hisao Furukawa, Coastal wetlands of Indonesia; Environment, subsistence and exploitation. Translated by Peter Hawkes. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press, 1994, vii + 219 pp., tables, figures, index. - C. van Dijk, Virginia Matheson Hooker, Culture and society in New Order Indonesia, Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1993, xxiii + 302 pp. - M.R. Fernando, Frans van Baardewijk, The cultivation system, Java 1834-1880, Changing Economy in Indonesia 14. Amsterdam: Royal Tropical Institute, 1993, 327 pp. - Bernice D. de Jong Boers, Jacqueline Vel, The Uma-economy; Indigenous economics and development work in Lawonda, Sumba (Eastern Indonesia). PhD thesis Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen, 1994, viii + 283 pp. Maps, tables, photographs, glossary. - Marijke J. Klokke, Lydia Kieven, Arjunas Askese; Ihre Darstellung im altjavanischen Arjunawiwaha und auf ausgewählten ostjavanischen Reliefs. Kölner Südostasien Studien Bd. 2. Bonn: Holos, 1994, 154 pp. - Marijke J. Klokke, Edi Sedyawati, Ganesa statuary of the Kadiri and Sinhasari periods; A study of art history. Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 160. Leiden: KITLV Press 1994. - Gijs Koster, Annabel Teh Gallop, The legacy of the Malay letter - Warisan warkah Melayu. With an essay by E. Ulrich Kratz. London: British Library for the National Archives of Malaysia, 1994, 240 pp. - Stephen Markel, Marijke J. Klokke, Ancient Indonesian Sculpture, Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 165. Leiden: KITLV Press 1994, vii + 210 pp., Pauline Lunsingh Scheurleer (eds.) - Anke Niehof, Ingrid Rudie, Visible women in East coast Malay society; On the reproduction of gender in ceremonial, school and market. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press, 1994, xi + 337 pp. - Peter Pels, Nicholas Thomas, Colonialisms culture; Anthropology, travel and government. -

The Influence of History on Modern Chinese Strategic Thinking

THE INFLUENCE OF HISTORY ON MODERN CHINESE STRATEGIC THINKING By S. Elizabeth Speed, Ph.D. 106 - 1386 West 73rd Avenue, Vancouver, B.C., V6P 3E8. February '5'&5''&& PWGSC Contract Number: WW7714-15-6105 Contract Scientific Authority: Ben Lombardi – Strategic Analyst 7KHVFLHQWLILFRUWHFKQLFDOYDOLGLW\RIWKLV&RQWUDFW5HSRUWLVHQWLUHO\WKHUHVSRQVLELOLW\RIWKH&RQWUDFWRUDQGWKH FRQWHQWVGRQRWQHFHVVDULO\KDYHWKHDSSURYDORUHQGRUVHPHQWRI'HSDUWPHQWRI1DWLRQDO'HIHQFHRI&DQDGD +HU0DMHVW\WKH4XHHQLQ5LJKWRI&DQDGDDVUHSUHVHQWHGE\WKH0LQLVWHURI1DWLRQDO'HIHQFH7 6D0DMHVWpOD5HLQH HQGURLWGX&DQDGD WHOOHTXHUHSUpVHQWpHSDUOHPLQLVWUHGHOD'pIHQVHQDWLRQDOH7 1 Note to Readers This paper represents the first section of what was supposed to be a much larger study to examine the influence that history has on modern Chinese strategic thinking, including contemporary force development considerations. Unfortunately, the author, Elizabeth Speed, was unable to complete the project due to health concerns. Rather than toss aside the useful analysis that was already prepared when she had to withdraw, the decision was taken to publish the portion of the project that was completed. The focus of this project was always very ambitious. With a recorded history of nearly three millennia, any attempt to derive “lessons” from such a record would be extremely difficult. As Dr. Speed indicates in this paper, it would also likely fail. Nevertheless, it is probable that the enormity of China’s national history is why so many people have resorted to cherry-picking that record. At no time is this more evident than in our own age when, as China regains a leading position in global affairs, observers are actively endeavouring to understand what this might mean for the future. What can that country’s past tell us – many of whom are not Sinologists – about its likely actions in the future? It is a truism to assert that history influences the current generation of Chinese leaders. -

Texas and the Great War Travel Guide

Credit: Wikimedia Commons In the 1916 presidential election, Woodrow Wilson In many ways, World War I is a forgotten war, campaigned on “He Kept Us Out of War.” While the Great overshadowed by the major conflicts that preceded and War raged abroad, this slogan reassured Americans that followed it. But its impact was profound. It normalized their boys would not be shipped off to the killing fields of airplanes in skies and made death by machine gun, poison Europe. But on April 6, 1917, just a month after Wilson’s gas, or artillery the new normal for soldiers. It catalyzed second inauguration, the U.S. found itself joining the fight reform movements, invigorated marginalized groups, that in just three years had brought powerful empires to and strained America’s commitment to the protection of their knees. civil liberties within its own borders. It did all this while turning the U.S. into a creditor nation for the first time The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria- in its history, and granting it a new—albeit temporary— Hungary by Serbian separatists was the spark that ignited importance on the international stage. The U.S., and a bold, the war. It was fueled by an ongoing arms race, rising modern new world, had finally arrived. nationalism, and decades of resentment and competition between powerful European nations. Dozens of nations and Texas was at the forefront of much of this change. colonial territories eventually aligned themselves behind Thousands of its residents, along with new migrants from one of two opposing power blocs: the Triple Entente (or the rest of the U.S. -

Maritime Trade and State Development in Early Southeast Asia Maritime Trade and State Development in Early Southeast Asia Ii

Maritime Trade and State Development in Early Southeast Asia Maritime Trade and State Development in Early Southeast Asia ii Maritime Trade and State Development in Early Southeast Asia Kenneth R. Hall Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824882082 (PDF) 9780824882075 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1985 UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED To Randy, Janie, and Jason Contents Contents DEDICATION vi MAPS viii FIGURES ix LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHS x PREFACE xi 1 TRADE AND STATECRAFT IN EARLY SOUTHEAST ASIA 1 2 THE DEVELOPMENT OF MARITIME TRADE IN ASIA 28 3 THE “INDIANIZATION” OF FUNAN, SOUTHEAST ASIA’S FIRST STATE 52 4 TRADE AND STATECRAFT IN EARLY ŚRĪVIJAYA 85 5 THE ŚAILENDRA ERA IN JAVANESE HISTORY 113 6 TEMPLES AS ECONOMIC CENTERS IN EARLY CAMBODIA 148 7 ELEVENTH-CENTURY COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENTS IN ANGKOR AND CHAMPA 183 8 TRANSITIONS IN THE SOUTHEAST ASIAN COMMERCIAL AND POLITICAL REALMS, A.D. -

The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 23 Issue 2 Spring 2013 Article 5 Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories Salome Kiwara-Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Recommended Citation Salome Kiwara-Wilson, Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories, 23 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 375 (2013) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol23/iss2/5 This Seminar Articles is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kiwara-Wilson: Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and RESTITUTING COLONIAL PLUNDER: THE CASE FOR THE BENIN BRONZES AND IVORIES Africa needs not only apology and forgiveness, but that these priceless African cultural treasures - artworks, icons, relics - be returned to their rightful owners... [T]he African art that has found its way into the galleries of former European colonial powers and the homes of the rich in North America, Europe, and elsewhere has deep cultural significance. These works form an integral part of defining our identity and personality as family, as African family. We talk to them. They talk to us. We touch them at certain moments of our lives, from birth through life to death. It is through them that the living spirits of our people, of our history, of our culture interact and interface with us. -

Bowl Round 2

IHBB New Zealand Set 2016 Bowl Round 2 Bowl Round 2 First Quarter (1) In this city, Ezra Pound and Igor Stravinsky are buried on the island oF San Michele [pr. mick-AY-lay]. One traveler From this city was imprisoned in Genoa, where Rustichello da Pisa recorded his stories in the work Il Milione [pr. mill-YOH-nay]. The admirer oF the Polish boy Tadzio, Gustav von Aschenbach, dies in this city in a 1912 novella by Thomas Mann. Marco Polo was From, For ten points, what Italian city, Famous For its canals? ANSWER: Venice (or Venezia) (2) Sigmund Rascher’s experiments were used to test technology For this military Force. Members oF this group carried out the Stalag LuFt III murders after a group of Allied POWs escaped From one of their prisons. Its leader committed suicide after being sentenced to death during the Nuremberg Trials. The Junkers [pr. yoon- kers] Ju-87 was heavily used by this organization For dive-bombing. Herman Goering led, For ten points, what branch oF the Nazi military that bombed Britain? ANSWER: Luftwaffe (accept the Nazi Air Force or German Air Force; prompt on partial answers such as Air Force or Nazi Germany) (3) An 1896 law that restricted this action issued a 100 pound poll tax and required ships to carry 200 tons of cargo For each passenger perForming it. That law, which was issued 14 years after a similar "Exclusion Act" in the United States, noted it was "expedient to safeguard the race-purity oF the people oF New Zealand." The Asiatic Restriction Act limited, For ten points, what action taken by tens of thousands of Foreigners each year, who receive visas or residency to live in New Zealand? Answer: immigrating (to New Zealand From Asia) (4) This man is shown with his right arm outstretched in The Distribution of the Eagle Standards.