The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benin Kingdom • Year 5

BENIN KINGDOM REACH OUT YEAR 5 name: class: Knowledge Organiser • Benin Kingdom • Year 5 Vocabulary Oba A king, or chief. Timeline of Events Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means 900 CE Lots of villages join together and make a “Rulers of the Sky”. kingdom known as Igodomigodo, ruled by Empire lots of countries or states, all ruled by the Ogiso. one monarch or single state. c. 900- A huge earthen moat was constructed Guild A group of people who all do the 1460 CE around the kingdom, stretching 16.000 km same job, usually a craft. long. Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 1180 CE The Oba royal family take over from the Voodoo The belief that non-human objects Osigo, and begin to rule the kingdom. (or Vodun) have spirits or souls. They are treated like Gods. Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as 1440 CE Benin expands its territory under the rule of Oba Ewuare the Great. a kind of money to trade with African leaders. 1470 CE Oba Ewuare renames the kingdom as Civil war A war between people who live in the Edo, with it;s main city known as Ubinu (Benin in Portuguese). same country. Moat A long trench dug around an area to 1485 CE The Portuguese visit Edo and Ubinu. keep invaders out. 1514 CE Oba Esigie sets up trading links with the Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Portuguese, and other European visitors. country by force, and live among the 1700 CE A series of civil wars within Benin lead to people. -

Round 3 Bowl Round 3 First Quarter

NHBB A-Set Bowl 2016-2017 Bowl Round 3 Bowl Round 3 First Quarter (1) This author of Postcards from the Edge wrote multiple autobiographical works that openly discuss her positive experience with electroconvulsive therapy as treatment for bipolar disorder. This author of the memoir The Princess Diarist is, with her mother, the subject of Bright Lights, a documentary that premiered on HBO in January 2017, just weeks after their deaths. For ten points, name this mental health advocate, daughter of Debbie Reynolds, and actress who portrayed Princess Leia in the Star Wars films. ANSWER: Carrie Fisher (2) Oscar L´opez Rivera, an independence activist for this territory, had his prison sentence commuted during Barack Obama's last week in office. In 2016, this territory was blocked from declaring bankruptcy by the Supreme Court. Like Guam and the Philippines, this commonwealth's ownership transferred to the U.S. after the Spanish-American War. For ten points, name this Caribbean island territory where activists in its capital, San Juan, wish to become the 51st U.S. state. ANSWER: Puerto Rico (3) These people discovered a \land of stone slabs" that might be the Torngat Mountains. These people harvested lumber from Markland and recorded finding grapes in another area. These people battled against Skraelings and found grapes during their brief settlements in Vinland and at L'Anse Aux Meadows. The first European peoples to land in Canada were, for ten points, what Scandinavians, including the explorer Leif Ericsson? ANSWER: Norsemen (or Vikings; accept Danes or Greenlanders; prompt on Scandinavians before mentioned) (4) This group regularly held meetings at the Menger Hotel Bar of San Antonio. -

Wikimedia with Liam Wyatt

Video Transcript 1 Liam Wyatt Wikimedia Lecture May 24, 2011 2:30 pm David Ferriero: Good afternoon. Thank you. I’m David Ferriero, I’m the Archivist of the United States and it is a great pleasure to welcome you to my house this afternoon. According to Alexa.com, the internet traffic ranking company, there are only six websites that internet users worldwide visit more often than Wikipedia: Google, Facebook, YouTube, Yahoo!, Blogger.com, and Baidu.com (the leading Chinese language search engine). In the States, it ranks sixth behind Amazon.com. Over the past few years, the National Archives has worked with many of these groups to make our holdings increasingly findable and accessible, our goal being to meet the people where they are. This past fall, we took the first step toward building a relationship with the “online encyclopedia that anyone can edit.” When we first began exploring the idea of a National Archives-Wikipedia relationship, Liam Wyatt was one of, was the one who pointed us in the right direction and put us in touch with the local DC-area Wikipedian community. Early in our correspondence, we were encouraged and inspired when Liam wrote that he could quote “quite confidently say that the potential for collaboration between NARA and the Wikimedia projects are both myriad and hugely valuable - in both directions.” I couldn’t agree more. Though many of us have been enthusiastic users of the Free Encyclopedia for years, this was our first foray into turning that enthusiasm into an ongoing relationship. As Kristen Albrittain and Jill James of the National Archives Social Media staff met with the DC Wikipedians, they explained the Archives’ commitment to the Open Government principles of transparency, participation, and collaboration and the ways in which projects like the Wikipedian in Residence could exemplify those values. -

What Was Life Like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’S Enquiry: Why Is It Important to Learn About Benin in School?

History Our main enquiry question this term: What was life like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’s enquiry: Why is it important to learn about Benin in school? Benin Where is Benin? Benin is a region in Nigeria, West Africa. Benin was once a civilisation of cities and towns, powerful Kings and a large empire which traded over long distances. The Benin Empire 900-1897 Benin began in the 900s when the Edo people settled in the rainforests of West Africa. By the 1400s they had created a wealthy kingdom with a powerful ruler, known as the Oba. As their kingdom expanded they built walls and moats around Benin City which showed incredible town planning and architecture. What do you think of Benin City? Benin craftsmen were skilful in Bronze and Ivory and had strong religious beliefs. During this time, West Africa invented the smelting (heating and melting) of copper and zinc ores and the casting of Bronze. What do you think that this might mean? Why might this be important? What might this invention allowed them to do? This allowed them to produced beautiful works of art, particularly bronze sculptures, which they are famous for. Watch this video to learn more: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zpvckqt/articles/z84fvcw 7 Benin was the center of trade. Europeans tried to trade with Benin in the 15 and 16 century, especially for spices like black pepper. When the Europeans arrived 8 Benin’s society was so advanced in what they produced compared with Britain at the time. -

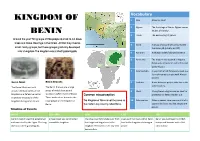

Kingdom of Benin Is Not the Same As 10 Colonisation When Invaders Take Over Control of a Benin

KINGDOM OF Vocabulary 1 Oba A king or chief. 2 Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means BENIN ‘Rulers of the Sky’. 3 Trade The exchanging of goods. Around the year 900 groups of Edo people started to cut down trees and make clearings in the forest. At first they lived in 4 Guild A group of people who all complete small family groups, but these groups gradually developed the same job (usually a craft). into a kingdom. The kingdom was called Igodomigodo. 5 Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 6 Benin city The modern city located in Nigeria. Previously, it has been called Edo and Igodomigodo. 7 Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as a form of money to trade with African leaders. Benin Moat Benin Bronzes 8 Civil war A war between people who live in the same country. The Benin Moat was built The Benin Bronzes are a large around the boundaries of the group of metal plaques and 9 Moat A long trench dug around an area for kingdom as a defensive barrier sculptures (often made of brass). Common misconception protection to keep invaders out. to protect the people of the These works of art decorate the kingdom during times of war. royal palace of the Kingdom of The Kingdom of Benin is not the same as 10 Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Benin. the modern day country called Benin. country by force, and live among the people. Timeline of Events 900 AD 900—1460 1180 1700 1897 Benin Kingdom was first established A huge moat was constructed The Oba royal family take over from A series of civil wars within Benin Benin was destroyed by British and was ruled by the Ogiso. -

1 Ancient America and Africa

NASH.7654.cp01.p002-035.vpdf 9/1/05 2:49 PM Page 2 CHAPTER 1 Ancient America and Africa Portuguese troops storm Tangiers in Morocco in 1471 as part of the ongoing struggle between Christianity and Islam in the mid-fifteenth century Mediterranean world. (The Art Archive/Pastrana Church, Spain/Dagli Orti) American Stories Four Women’s Lives Highlight the Convergence of Three Continents In what historians call the “early modern period” of world history—roughly the fif- teenth to the seventeenth century, when peoples from different regions of the earth came into close contact with each other—four women played key roles in the con- vergence and clash of societies from Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Their lives highlight some of this chapter’s major themes, which developed in an era when the people of three continents began to encounter each other and the shape of the mod- ern world began to take form. 2 NASH.7654.cp01.p002-035.vpdf 9/1/05 2:49 PM Page 3 CHAPTER OUTLINE Born in 1451, Isabella of Castile was a banner bearer for reconquista—the cen- The Peoples of America turies-long Christian crusade to expel the Muslim rulers who had controlled Spain for Before Columbus centuries. Pious and charitable, the queen of Castile married Ferdinand, the king of Migration to the Americas Aragon, in 1469.The union of their kingdoms forged a stronger Christian Spain now Hunters, Farmers, and prepared to realize a new religious and military vision. Eleven years later, after ending Environmental Factors hostilities with Portugal, Isabella and Ferdinand began consolidating their power. -

Sir Hugh Casson Interviewed by Cathy Courtney: Full Transcript of the Interview

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH NATIONAL LIFE STORIES LEADERS OF NATIONAL LIFE Sir Hugh Casson Interviewed by Cathy Courtney C408/16 This transcript is copyright of the British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] IMPORTANT Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators ([email protected]) British Library Sound Archive National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C408/16/01-24 Playback no: F1084 – F1093; F1156 – F1161; F1878 – F1881; F2837 – F2838; F6797 Collection title: Leaders of National Life Interviewee’s surname: Casson Title: Mr Interviewee’s forename: Hugh Sex: Male Occupation: Architect Date and place of birth: 1910 - 1999 Mother’s occupation: Father’s occupation: Dates of recording: 1990.02.13, 1990.02.16, 1990.02.19, 1990.03.13, 1990.04.19, 1990.05.11, 1990.05.22, 1990.08.28, 1990.07.31, 1990.08.07, 1991.05.22, 1991.06.03, 1991.06.18, 1991.07.13 Location of interview: Interviewer's home, National Sound Archive and Interviewee's home Name of interviewer: Cathy Courtney Type of recorder: Marantz CP430 Type of tape: TDK 60 Mono or stereo: Stereo Speed: N/A Noise reduction: Dolby B Original or copy: Original Additional material: Copyright/Clearance: Interviewer’s comments: Sir Hugh Casson C408/016/F1084-A Page 1 F1084 Side A First interview with Hugh Casson - February 13th, 1990. -

The Translation of the Benin Bronzes in 19

Golf in the City of Blood: the Translation of the Benin Bronzes in th 19 Century Britain and Germany Manuela Husemann Sir,—Foreigners have often been known to state that wherever an Englishman wanders in distant parts of the globe, the safety-valve to his excessive vitality must be appealed by knocking about a ball in some form or other. Now, few people reading their morning papers three months ago at home, with the horrors of city so graphically depicted, would have conjectured that within four weeks of the final charge on the city walls, the ringing sound of the cleek and the call of "Fore!" would be heard resounding in the same sanguinary vicinity. Such was the case, however, a good nine-hole course (which would compare very favourably with many British inland courses) being at that time in full swing and working order. […] The chief drawback we found on first starting was the huge quantity of human skulls and bones which littered the course ; and, sad as it is to state, our best green happens to have been made on the turf immediately beneath a tree known as the "crucifixion tree," on which many a poor slave breathed his last. I am, Sir, &c, Benin City, West Africa, C. H. P. C. April 18th. 1897.1 This letter, originally headed Golf in ‘the City of Blood,’ was written by an officer stationed in Benin City. It does not just provide an interesting title for this paper, but it additionally gives 1 Friday June the 18th 1897 Golf: A Weekly Record of Ye Royal and Ancient Game, p. -

The Dawn of American Cryptology, 1900–1917

United States Cryptologic History The Dawn of American Cryptology, 1900–1917 Special Series | Volume 7 Center for Cryptologic History David Hatch is technical director of the Center for Cryptologic History (CCH) and is also the NSA Historian. He has worked in the CCH since 1990. From October 1988 to February 1990, he was a legislative staff officer in the NSA Legislative Affairs Office. Previously, he served as a Congressional Fellow. He earned a B.A. degree in East Asian languages and literature and an M.A. in East Asian studies, both from Indiana University at Bloomington. Dr. Hatch holds a Ph.D. in international relations from American University. This publication presents a historical perspective for informational and educational purposes, is the result of independent research, and does not necessarily reflect a position of NSA/CSS or any other US government entity. This publication is distributed free by the National Security Agency. If you would like additional copies, please email [email protected] or write to: Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Suite 6886 Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755 Cover: Before and during World War I, the United States Army maintained intercept sites along the Mexican border to monitor the Mexican Revolution. Many of the intercept sites consisted of radio-mounted trucks, known as Radio Tractor Units (RTUs). Here, the staff of RTU 33, commanded by Lieutenant Main, on left, pose for a photograph on the US-Mexican border (n.d.). United States Cryptologic History Special Series | Volume 7 The Dawn of American Cryptology, 1900–1917 David A. -

Renouncing the Universal Museum's Imperial Past: a Call to Return The

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Fall 12-14-2018 Renouncing the Universal Museum’s Imperial Past: A Call to Return the Rosetta Stone Through Collaborative Museology Anna Volante [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Museum Studies Commons Recommended Citation Volante, Anna, "Renouncing the Universal Museum’s Imperial Past: A Call to Return the Rosetta Stone Through Collaborative Museology" (2018). Master's Projects and Capstones. 876. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/876 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Renouncing the Universal Museum’s Imperial Past: A Call to Return the Rosetta Stone Through Collaborative Museology Keywords : Cultural Heritage, Rosetta Stone, Rashid, Egypt, Colonialism, Imperialism, Orientalism, Repatriation, Collaborative Museology, Universal Museums, Museum Studies by Anna J. Volante Capstone project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Museum Studies Department of Art + Architecture University of San Francisco ______________________________________________________________________________ Faculty Advisor: Stephanie A. Brown ______________________________________________________________________________ Academic Director: Paula Birnbaum December 14, 2018 Abstract In colonial times, Western empires used orientalism to justify and perpetuate colonialism and imperialism over countries that they believed inferior to their own. -

Basic Information

BRITISH MUSEUM Caroline Tully School of Historical and Philosophical Studies University of Melbourne Melbourne, Victoria Australia [email protected] Basic Information Situated in Great Russell Street, London, the British Museum (http://www.britishmuseum.org/) was created by an Act of Parliament in 1753 and opened to the public in 1759. Governed by a board of 25 trustees in accordance with the British Museum Act of 1963 and the Museums and Galleries Act of 1992, the museum is a non-departmental public body, sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. The museum’s stated purpose is “to hold for the benefit and education of humanity a collection representative of world cultures and to ensure that the collection is housed in safety, conserved, curated, researched and exhibited” (British Museum n.d.). The British Museum originated with the collection belonging to physician and naturalist, Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), which consisted of natural history specimens, ethnographic material, antiquities, jewellery, coins, medals, prints, and orientalia. This was combined with a large library of manuscripts assembled by Sir Robert Cotton, and the Harleian Library, the manuscript collection of the earls of Oxford. Expanded in 1757 with the addition of King George II’s donation of the old Royal Library, the museum thus originally mainly consisted of natural history specimens, books and manuscripts. In 1772 the museum acquired its first collection of notable antiquities with the Greek vases belonging to Sir William Hamilton. In 1807 it created a specific Department of Antiquities which, in 1860, was divided into three: Greek and Roman Antiquities; Oriental Antiquities; and Coins and Medals. -

Igue Festival and the British Invasion of Benin 1897: the Violation of a People’S Culture and Sovereignty

Vol. 6(1), pp. 1-5, March, 2014 DOI: 10.5897/AJHC2013.0170 African Journal of History and Culture ISSN 2141-6672 Copyright © 2014 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJHC Full Length Research Paper Igue festival and the British invasion of Benin 1897: The violation of a people’s culture and sovereignty Charles .O. Osarumwense Department of History and International Studies, University of Benin, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria. Accepted 18 December, 2013 The Benin Kingdom was a sovereign state in pre-colonial West Africa. Sovereign in the sense that the Kingdom conducted and coordinated its internal and external affairs with its well structured political, social-cultural and economic institutions. One remarkable aspect of the Benin culture was the Igue festival. The festival was unique in the sense that it was a period when the Oba embarks on spiritual cleansing and prayers to departed ancestors for continued protection and growth of the land. The period of the festival was uncompromising and was spiritually adhered to. It was during this period that the British attempted to visit the Oba. This attempted visit to the land was declined by the Oba. An imposition of the visit by the British Crown resulted in the ambushed and killing of British officers. This incident marked the road map to the British invasion of the Kingdom in 1897. This study presents the sovereign nature of the Benin Kingdom, its social-cultural and economic uniqueness rooted in the belief and respect of deities. The paper further argues that the event of 1897 was a clear cut violation of the sovereignty, culture and territorial rights of the Benin Kingdom under a crooked agreement called the Gallwey Treaty of 1892.