The Mvmuseum Quarterly, February 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NANTUCKET HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Nantucket Historic District Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Not for publication: City/Town: Nantucket Vicinity: State: MA County: Nantucket Code: 019 Zip Code: 02554, 02564, 02584 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): Public-Local: X District: X Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 5,027 6,686 buildings sites structures objects 5,027 6,686 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 13,188 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NANTUCKET HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Points of Interest

History Welcomes You Ashore in Massachusetts Massachusetts is steeped in history; we’re the home to the Pilgrims’ landing, the Revolutionary War, treasured national authors and more ‘firsts’ than you can count! We’re also home to nine historic ports including Gloucester, America’s oldest fishing port and Boston Harbor, an active trading port since the early 1600s. For centuries, our ports and their coastal communities have beckoned sea captains, sailors, neighbors and visitors to gather, enjoy the natural landscape beauty and the many bounties of the sea. As you stroll through the seaside villages of the nine Historic Ports of Massachusetts, you’ll be captivated by the stature and architecture of charming homes once occupied by sea captains and their families and you’ll find a soothing simplicity in the natural beauty of windswept dunes, inspirational sunrises and miles of sandy beaches. Each port’s unique community welcomes you with talented artisans, hidden treasures and the freshest seafood anywhere! Come explore the distinctive nooks and crannies of the Historic Ports of Massachusetts --- welcome ashore! Points of Interest Gloucester Provincetown New Bedford Gloucester Fisherman’s Memorial Pilgrim Monument New Bedford Whaling Museum Cape Ann Museum National Seashore Park Buttonwood Park Zoo Wingaersheek & Good Harbor Beaches Race Point Light Fort Rodman Hammond Castle Provincetown Art Association Seamen’s Bethel Cape Ann Brewing Company & Brewpub Art’s Dune Tours Zeiterion Performing Arts Center Ryan & Wood Distilleries Provincetown Ghost Tours Rotch-Jones-Duff House and Garden Salem Plymouth Martha’s Vineyard Peabody Essex Museum Pilgrim Memorial State Park Flying Horses Carousel The House of the Seven Gables Myles Standish State Forest Joseph Silvia State Beach Salem Witch Museum Plimoth Plantation Aquinnah Cliffs Pickering Wharf Plymouth Harbor & Mayflower II Gingerbread Cottages Salem Ferry Plymouth Rock Mytoi Gardens Capt. -

Martha, the Worker-Bee Sister of Mary and Lazarus of Bethany

My Thoughts For Sunday, 15 March 2015 Women of the Bible---Part 3---Martha, The Worker-bee Sister of Mary and Lazarus of Bethany I like the term the American Bible Society pinned on Martha, It seems very fitting. However, besides being what we term today as a workaholic, Martha had some much deeper traits and tendencies that can be of great example to many, if not all, of us today as we follow ever closer in the footsteps of Jesus. Their term for Martha was "worker-bee" which in today's society might be translated as a workaholic, one who never seems to run out of menial tasks to undertake. Perhaps you know one of these types, or maybe you are one yourself. I know I have gone through times in my life when that title was tied to me for lengthy periods. It seemed that there was always so much to do and so little time. Martha had one of these periods in her life that was recorded for our benefit and instruction. This is recorded for us at Luke 10:38-40 (NIV2011) "As Jesus and his disciples were on their way, he came to a village where a woman named Martha opened her home to him. She had a sister called Mary, who sat at the Lord’s feet listening to what he said. But Martha was distracted by all the preparations that had to be made. She came to him and asked, “Lord, don’t you care that my sister has left me to do the work by myself? Tell her to help me!” Here we see poor Martha working to get everything in order and attempting to get Jesus to take her side in the matter. -

Martha and Jesus Ardy Bass

“If you had been there” Martha and Jesus Ardy Bass (Published in The Bible Today, 32 [March 1994] 90 – 94) The only characters that are directly identified as friends of Jesus in the Gospel of John are Martha, Mary, and Lazarus in John 11:1-44. While John 15 teaches about the greatest gift between friends, Martha’s lament to Jesus (11:17-27) offers a window through which we offers a window through which we can reflect on friendship, our relationship to God, and faith. Friendship I Friendship implies a relationship that is intimate, and trusting, For friendship to thrive there weds to be shared values and concerns, common ideas, ideals, and worldview. This foundation allows friends to have influence over one another through discussion and disagreement. Friends hold each other accountable for their actions. They respect and accept each other, yet they are not afraid to confront each other when the need arises. Friends depend on one another for support in times of crisis, whether emotional or material. Friendship is a relationship of trust, confidence, and intimacy. Perhaps the human element of influence and accountability characteristic of friendship has silenced discussion about Jesus and its friends in the Gospels. Friendship vita Jesus would not be a common friendship, indeed, it is an uncommon relationship given Jesus' divinity. However, the Jewish religious tradition, of which Jesus and this friends were a part is rooted in an intimate, trusting relationship with God. The tradition of Lament In the Old Testament, faith is not assent to a set of beliefs. At least, the Bible does not define it as such. -

Beyond the Paths of Heaven the Emergence of Space Power Thought

Beyond the Paths of Heaven The Emergence of Space Power Thought A Comprehensive Anthology of Space-Related Master’s Research Produced by the School of Advanced Airpower Studies Edited by Bruce M. DeBlois, Colonel, USAF Professor of Air and Space Technology Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama September 1999 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beyond the paths of heaven : the emergence of space power thought : a comprehensive anthology of space-related master’s research / edited by Bruce M. DeBlois. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Astronautics, Military. 2. Astronautics, Military—United States. 3. Space Warfare. 4. Air University (U.S.). Air Command and Staff College. School of Advanced Airpower Studies- -Dissertations. I. Deblois, Bruce M., 1957- UG1520.B48 1999 99-35729 358’ .8—dc21 CIP ISBN 1-58566-067-1 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii OVERVIEW . ix PART I Space Organization, Doctrine, and Architecture 1 An Aerospace Strategy for an Aerospace Nation . 3 Stephen E. Wright 2 After the Gulf War: Balancing Space Power’s Development . 63 Frank Gallegos 3 Blueprints for the Future: Comparing National Security Space Architectures . 103 Christian C. Daehnick PART II Sanctuary/Survivability Perspectives 4 Safe Heavens: Military Strategy and Space Sanctuary . 185 David W. Ziegler PART III Space Control Perspectives 5 Counterspace Operations for Information Dominance . -

Historically Famous Lighthouses

HISTORICALLY FAMOUS LIGHTHOUSES CG-232 CONTENTS Foreword ALASKA Cape Sarichef Lighthouse, Unimak Island Cape Spencer Lighthouse Scotch Cap Lighthouse, Unimak Island CALIFORNIA Farallon Lighthouse Mile Rocks Lighthouse Pigeon Point Lighthouse St. George Reef Lighthouse Trinidad Head Lighthouse CONNECTICUT New London Harbor Lighthouse DELAWARE Cape Henlopen Lighthouse Fenwick Island Lighthouse FLORIDA American Shoal Lighthouse Cape Florida Lighthouse Cape San Blas Lighthouse GEORGIA Tybee Lighthouse, Tybee Island, Savannah River HAWAII Kilauea Point Lighthouse Makapuu Point Lighthouse. LOUISIANA Timbalier Lighthouse MAINE Boon Island Lighthouse Cape Elizabeth Lighthouse Dice Head Lighthouse Portland Head Lighthouse Saddleback Ledge Lighthouse MASSACHUSETTS Boston Lighthouse, Little Brewster Island Brant Point Lighthouse Buzzards Bay Lighthouse Cape Ann Lighthouse, Thatcher’s Island. Dumpling Rock Lighthouse, New Bedford Harbor Eastern Point Lighthouse Minots Ledge Lighthouse Nantucket (Great Point) Lighthouse Newburyport Harbor Lighthouse, Plum Island. Plymouth (Gurnet) Lighthouse MICHIGAN Little Sable Lighthouse Spectacle Reef Lighthouse Standard Rock Lighthouse, Lake Superior MINNESOTA Split Rock Lighthouse NEW HAMPSHIRE Isle of Shoals Lighthouse Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse NEW JERSEY Navesink Lighthouse Sandy Hook Lighthouse NEW YORK Crown Point Memorial, Lake Champlain Portland Harbor (Barcelona) Lighthouse, Lake Erie Race Rock Lighthouse NORTH CAROLINA Cape Fear Lighthouse "Bald Head Light’ Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Cape Lookout Lighthouse. Ocracoke Lighthouse.. OREGON Tillamook Rock Lighthouse... RHODE ISLAND Beavertail Lighthouse. Prudence Island Lighthouse SOUTH CAROLINA Charleston Lighthouse, Morris Island TEXAS Point Isabel Lighthouse VIRGINIA Cape Charles Lighthouse Cape Henry Lighthouse WASHINGTON Cape Flattery Lighthouse Foreword Under the supervision of the United States Coast Guard, there is only one manned lighthouses in the entire nation. There are hundreds of other lights of varied description that are operated automatically. -

Cape Cod Lighthouses TCCI

Cape Cod Lighthouses Locations Click on a lighthouse on the map for more information The climb up circular stairs to the top of a lighthouse tower is not for the squeamish or for those afraid of heights. Most lighthouses have interesting stories related to their history. Some are open to the public and have “visiting hours.” Others are open only on special occasions. Usually a tour guide will take you through the building and offer you tales of lighthouse living. The winding staircases, the distant echo of your footsteps, waves hitting against the rock, distant ship hooting…that’s the dejavu you get when you visit the Cape Cod Lighthouses. It is as if you are part of the whole system that emits navigational lights to guide hundreds of ships to dock safely. Lighthouses are navigational aids that mark the perilous reeds, hazardous shoals and poorly charted coastlines for safe harbor entry. Once upon a time, the lighthouses were the marine pilot’s most important aids but the advent of electronic navigation has led to their decline. The system of lights and lamps on the lighthouses are also expensive to maintain. The vantage points occupied by the lighthouses make them a tourists’ attraction. You’ll go up the winding staircase with your pair of binoculars and voila! The beautiful Cape Cod Coastline spreads right before your eyes. Race Point Light Located in Provincetown, Massachusetts, the Race Point Lighthouse is one of the historical building in the National Register of Historic Places. It was first built in 1816, but the current 45-foot tall tower was built in 1876. -

National Historic Landmark Nomination Cape Ann Light

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CAPE ANN LIGHT STATION (Thacher Island Twin Lights) Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Cape Ann Light Station Other Name/Site Number: Thacher Island Twin Lights 2. LOCATION Street & Number: One mile off coast of Rockport, Massachusetts. Not for publication: City/Town: Rockport Vicinity: X State: MA County: Essex Code: 009 Zip Code: 01966 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: Building(s): Public-Local: X District: X Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 4 buildings sites 2 2 structures objects 6 2 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 6 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: n/a (see summary context statement for Lighthouse NHL theme study) NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CAPE ANN LIGHT STATION (Thacher Island Twin Lights) Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

2016-2017 NHLPA Program Highlights Report National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act 2016-2017 NHLPA Program Highlights Report

GSA Office of Real Property Utilization and Disposal 2016-2017 NHLPA Program Highlights Report National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act 2016-2017 NHLPA Program Highlights Report Executive Summary Congress passed the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Purpose of the Report Act (NHLPA) in 2000 to recognize the importance of lighthouses and light stations (collectively called “lights”) for maritime traffic. This report provides Coastal communities and not-for-profit organizations (non-profits) 1. An overview of the NHLPA; also appreciate the historical, cultural, recreational, and educational value of these iconic properties. 2. The roles and responsibilities of the three Federal partner agencies executing the program; Over time and for various reasons, the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) may determine a light is excess property. Through the NHLPA, 3. Calendar Year1 2016 and 2017 highlights and historical Federal agencies; state and local governments; and non-profits disposal trends of the program; can obtain an excess historic light at no cost through stewardship 4. A discussion of reconciliation of changes from past reports; transfers. If suitable public stewards are not found for an excess light, the General Services Administration (GSA) will sell the light 5. A look back at lighthouses transferred in 2002, the first year in a public auction (i.e. a public sale). GSA transferred lights through the NHLPA program; and GSA includes covenants in the transfer documentation to protect 6. Case studies on various NHLPA activities in 2016 and 2017. and maintain the historic features of the lights. Many of these lights remain active aids-to-navigation (“ATONs”), and continue to guide maritime traffic under their new stewards, in coordination with the USCG. -

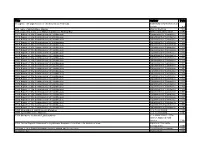

Lighthouse Bibliography.Pdf

Title Author Date 10 Lights: The Lighthouses of the Keweenaw Peninsula Keweenaw County Historical Society n.d. 100 Years of British Glass Making Chance Brothers 1924 137 Steps: The Story of St Mary's Lighthouse Whitley Bay North Tyneside Council 1999 1911 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1911 1912 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1912 1913 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1913 1914 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1914 1915 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1915 1916 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1916 1917 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1917 1918 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1918 1919 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1919 1920 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1920 1921 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1921 1922 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1922 1923 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1923 1924 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1924 1925 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1925 1926 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1926 1927 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1927 1928 Report of the Commissioner of -

Trip Planner U.S

National Park Service Trip Planner U.S. Department of the Interior Cape Cod National Seashore Seasonal listings of activities, events, and ranger programs are available at seashore visitor centers. NPS/MCQUEENEY Park Information Superintendent’s Message Cape Cod National Seashore Oversand Office at Race Point Mention Cape Cod National 99 Marconi Site Road Ranger Station Seashore and different thoughts Wellfleet, MA 02667 Route Information: come to mind. Certainly, for Superintendent: Brian Carlstrom 508-487-2100, ext. 0926 many, the national seashore is Email: [email protected] (April 15 through November 15) “the beach”—a place to recreate, rejuvenate, and forge lasting Park Headquarters, Wellfleet Permit Information: memories with family and friends. 508-771-2144 508-487-2100, ext. 0927 Other people are attracted to Fax: 508-349-9052 nature’s wildness. Change is an North Atlantic Coastal Lab ever-present force on the Outer Nauset Ranger Station, Eastham 508-487-3262 Cape, with wind, waves, and 508-255-2112 storms constantly shaping and reshaping the land. As the longest Emergencies: 911 NPS/KEKOA ROSEHILL Race Point Ranger Station, Provincetown continuous stretch of shoreline 508-487-2100 https://www.nps.gov/caco on the East Coast, the national seashore doesn’t just host sun-loving humans; it provides a refuge Salt Pond Visitor Center Province Lands Visitor Center for many species, including threatened shorebirds. Salt marshes and forests support a diverse array of plants and animals. And off-shore, Open daily from 9 am to 4:30 pm (later during Open daily from 9 am to 5 pm, mid-April to the ocean teems with life, including the microscopic plankton that the summer). -

Wind Energy Plan for Dukes County

Wind Energy Plan for Dukes County Adopted in October 2012 Wind Energy Plan for Dukes County 1 The Wind Energy Plan for Dukes County was adopted by the Martha’s Vineyard on October 16, 2012. The preparation of the Dukes County Wind Siting Plan was financed in part by the Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development – District Local Technical Assistance. Members of the Wind Energy Plan Task Force Gail Blout, Gosnold Board of Selectmen; John Breckenridge, MVC; Christina Brown, MVC; Kathy Burton, Oak Bluffs Board of Selectmen; Peter Cabana, MVC; Chris Fried, Tisbury Energy Committee; Andy Goldman, Chilmark Board of Selectmen; Richard Knabel, West Tisbury Board of Selectmen; Mike McCourt, Edgartown Planning Board; Carlos Montoya, Aquinnah Planning Board; Chris Murphy, MVC; Camille Rose, Aquinnah Board of Selectmen; Bruce Rosinoff, Vineyard Conservation Society; Leo Roy, Gosnold Energy Committee; Douglas Sederholm, MVC, Work Group Chairman ;Sander Shapiro, West Tisbury Energy Committee; Marnie Stanton, Tisbury Energy Committee Holly Stephenson, MVC; Richard Toole, Oak Bluffs Energy Committee ;Mark Wallace, Oak Bluffs Planning Board ;Janet Weidner, Chilmark Planning Board; Adam Wilson, Oak Bluffs Board of Selectmen; Alan Wilson, Edgartown Planning Board. Observers: Paul Pimentel, Vineyard Power; Tyler Studds. MARTHA’S VINEYARD COMMISSION P.O.BOX 1447 33 NEW YORK AVENUE OAK BLUFFS MA 02557 508.693.3453 FAX: 508.693 7894 [email protected] WWW.MVCOMMISSION.ORG REGIONAL PLANNING AGENCY OF DUKES COUNTY SERVING: AQUINNAH, CHILMARK, EDGARTOWN, GOSNOLD, OAK BLUFFS TISBURY, & WEST TISBURY Wind Energy Plan for Dukes County 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 7. Operational Considerations 7.1. Wind Availability and Access 2.